Forget the free bike map taped to your fridge. Forget the city’s terrific but frequently ignored 20-year bike plan. Forget the Bicycle Transportation Alliance’s map of its top 16 regional priorities, and even Metro’s long-term vision of a region with multiple urban centers and a huge grid of mass transit lines.

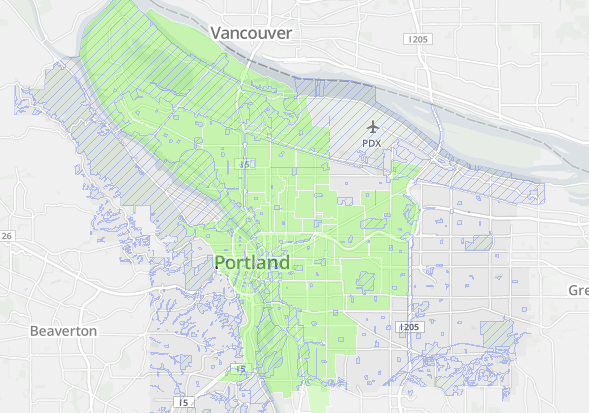

To understand the potential for where good urban transportation is currently within reach in Portland, you’ve got to look at the map above. Its green area shows “where the street grid meets connectivity standards and where the majority of the streets have sidewalks.”

Without a massive surge of political will, this is likely to be, for decades, the only area of Portland where most people will actually find it appealing to frequently get around without a car.

I don’t mean to say that biking, walking or skating is impossible or unpleasant in further-out neighborhoods. It’s not. And I’m not saying that efforts to improve things outside this area are useless. Just the opposite. But whatever the future brings, street connectivity is as close to destiny as things come in urban planning. It’s very, very hard to slice up private, developed land.

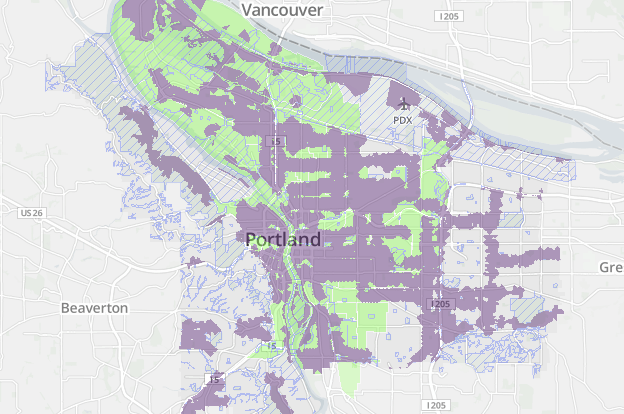

The new web mapping tool released this week by Portland’s Bureau of Planning and Sustainability is a revelation in part because it includes rarely-seen maps like this one. To show how important street connectivity is to the way a neighborhood works, here’s another: a map of connected neighborhoods in green, plus a map of everywhere in the city that’s currently within 1/4 mile of a “low-stress” bikeway such as a neighborhood greenway, buffered bike lane or off-street path.

It’s not that the city wouldn’t love to put neighborhood greenways all over Southwest and East Portland. But (despite substantial and much-needed recent investments) it hasn’t yet — because the grid isn’t connected. Maybe a person on foot can find a way through — but you can’t always do so, so it’s complicated. Which keeps people using cars, because who enjoys doing things that are complicated?

This isn’t just about biking. It’s about walking. And therefore it’s about transit, because every public transit trip starts and ends with a foot or bike trip, too. It’s hard to build transit ridership in neighborhoods where the only way to the bus stop is a crooked loop.

The need for more street connectivity is why Portland’s “Street by Street” effort to upgrade unpaved shoulders for use as low-quality footpaths exists. It’s also why crosswalks and connections through parks and schools are arguably more important to the East Portland in Motion plan than actual sidewalks are.

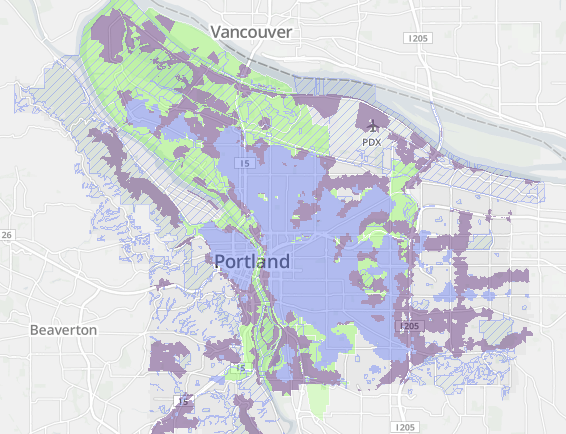

Finally, here’s another related map: one that combines the previous two maps with “places that are considered relatively complete on the 20-minute neighborhood index,” in blue. These are areas where people can live or work within walking distance of many of their regular needs.

It’s not a coincidence that these three maps are so similar. Areas that are well-connected and good for biking and walking are extremely desirable places to locate a business, because people like to spend time in them. They’re gushers of economic productivity; about 10 percent of all the property value in the entire state of Oregon sits inside the green and blue neighborhoods on this map. That’s not because the people who live and work there are inherently better than people in Bend, Medford or Sisters; it’s because these neighborhoods are built in such a way that they make valuable work possible.

Unfortunately, the fact is that since 1960 or so, we’ve been designing most new neighborhoods in a way that doesn’t make people’s most valuable work possible: we’ve been making them without connected street grids. Until those connections are finally built, the neighborhoods that don’t have them will continue to pay the price.

East Portland, Southwest Portland and the suburbs won’t be able to thrive until they’ve changed. But it’s going to be a harder job than any of us want to admit.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

There really is no getting around geometry. Density is important but we hear about that all the time. Connections are another geometric constraint that don’t seem to be mentioned as much. Maybe they should be.

I was with you until this point:

“because the grid isn’t connected. Maybe a person on foot can find a way through — but you can’t always do so, so it’s complicated. Which keeps people using cars, because who enjoys doing things that are complicated?” (emphasis mine)

Perhaps I’m misunderstanding you, but to me one of the chief delights of relying on a bike is that–unlike sitting in a car–I can go just about anywhere, and often with ease, and quickly too. I need far less special infrastructure than if I were in a car. Stairs are really the only piece of infrastructure I can think of that work for someone walking but not for someone on a bike. Otherwise both modes seem to me to be head and shoulders above driving when it comes to navigational ease in areas that may not be built out/up/in/whatever.

The fact that googlemaps’ algorithm gives me 45 right turns and 46 left turns instead of letting me go straight down Foster is asymmetrically ‘complicated,’ but that’s a different matter.

Good questions/points. The problem isn’t that the process of improvising by bike or foot per se is difficult when connectivity is bad. I totally share your experience: the most frustrating experiences I’ve had on a road have been when I used to drive to East Vancouver to report a story for the Columbian, make a single wrong turn and then spend 10 minutes getting back on track.

One problem with bad connectivity, I think, is that it reduces the payoff of improvisation. The other problem is that even when you know the way, it increases the distance traveled, which is way worse for active transportation than auto transportation.

When I visit my sister in exurban Seattle, I often get to her subdivision by bus. Once, I got off at the wrong stop, tried to navigate there by foot without knowing the connections and lost 20 minutes. A local resident might know the right connections better than I did … but they just as easily might never bother to figure it out. (Not to mention the fact that ~20% of Portlanders relocate in any given year and never have a chance to understand their neighborhoods in detail.) Cul-de-sac development is optimized to move people quickly between work, major commercial arterials, and home — nowhere new, and nowhere else.

O.K. I think I’m following. Like when I took the 205 bikepath South toward Flavel for the first time and every time the path encountered a cross street instead of having a sensible, direct path across those streets I was first directed right, sometimes quite a bit to the right, dumped at an intersection without any signage helping me reconnect with the path on the far side of the intersection, which I knew was to my left, but frequently there was no obvious way to judge how to do this.

Layout, signage, etc. is *much* better if you’re in a car/on the wide fast road, and unless you are willing to take the same route/cover a greater distance, you’re probably screwed.

Exactly. And this is why the Dutch win with their simple, straightforward off-street cycle track “bicycle superhighways” – you really don’t need to think too much about how to get somewhere, as you KNOW the route connects to where you’re gonig.

To illustrate this effect, use google maps/bicycling to plot a route across town. Last time I did it, it made me make ~50 turns! By car, it was 6. This practically requires you to have a Ph.D in urban navigation.

Your analysis is spot on. Portland planners over the last 35 years have been good at reclaiming the value of these inner neighborhoods by building on the “good bones” of the past. Old street grids and streetcar-era commercial districts make good places.

But our planning over that same time frame for outer east Portland has not succeeded to the same degree. Outer East Portland has densified tremendously, but it was done on the bones of the auto-oriented suburbs. Frankly, it doesn’t work.

Thankfully, people in the City are starting to recognize this and are trying to do something about it. If you want to see how we might be able to complete street grids and build new connections, keep an eye on the new Division-Midway planning:

http://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/63384

There’s also an existing plan to improve connectivity in the Gateway commercial center area. It just needs to be implemented.

The current strategy is to rely on the goodwill of property owners to make the improvements as they develop or redevelop their lots. At some point, we’re going to have to consider exercising eminent domain, particularly where the land is vacant or extremely underutilized.

Can you direct me to the source of the “10% of all property value in Oregon” statistic within that linked document? That’s really interesting. Would also be interesting to express comparatively, i.e., “close-in, highly-connected neighborhoods produce x times more value per acre than does less urbanized land.” This is totally in line with work Joe Minicozzi has been doing: http://www.planetizen.com/node/53922

Exactly what I was thinking with that paragraph, benschon — that figure is just a very conservative stab based on the total property value of Multnomah County, which has 22% of the total assessed property value of the state. I figured “about 10%” was safe for the blue and green areas mentioned.

I did look into this a little on a property-by-property basis, too: I used the county GIS sites to check the market value of the lots underneath a couple mansions in the West Hills and Lake Oswego and compared to some single-family homes in the SE Chavez and NW 23rdish areas. Sure enough, land values per acre are far higher (like 5x-10x) in the urban grid than in the glitzy cul-de-sacs. If you include the value of the improvements, the city’s advantage is even more pronounced because the fancy houses are on bigger lots, but it seems to me that land value is the better basis for comparison.

One of Minicozzi’s arguments, however, is that we systematically underestimate land value in property tax assessments. I know nothing about this process. Does anybody here?

> One of Minicozzi’s arguments, however, is that we systematically underestimate land value in property tax assessments. I know nothing about this process. Does anybody here?

Michael, I think this answers it, let me know if not:

“The flaw of our current property tax system is that when it comes to assessing how much a property owner owes, we place very little value on the land beneath a building as compared to the building itself. Compounding that issue is the fact that if you construct a building without innovative architecture or sustainable materials, you actually benefit by lower tax value. The combination of these two factors creates a disincentive for good architecture. The result is that the community loses, both in terms of the property tax it collects and the long-term legacy of cheap single-use buildings. In basic terms, we’ve created tax breaks to construct disposable buildings, and there’s nothing smart about that kind of growth.” [1]

Unlike buildings, the state has a fixed and limited amount of land — unless Oregon expands into the Ocean or steals from neighboring states — so it seems logical to use a land value taxation system [2] that would create incentives for efficiently using that land.

Also, “… it does not make sense to compare differing land uses based on the total tax revenue they generate. Instead, comparisons should be made on a per acre basis. For example, a large, box retailer that takes five acres of land pays $14,000 in property taxes versus a small, locally-owned store that only requires a quarter acre will only pay $1,200 per year in taxes. At face value, the box retailer means more for the city’s bottom line, but when compared on a per acre basis, $2,860 and $4,960 respectively, creating more space for mom-and-pop stores makes much more sense (Marohn, 2012).” [3]

Finally, check out the map at the bottom of this Atlantic Cities article [4], which shows a 3D view of a city where lot height is determined by taxes.

1: http://www.planetizen.com/node/53922 “The Smart Math of Mixed Use Development” by Joe Minicozzi

2: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Land_value_tax

3: http://www.gazarian.info/2013/11/making-city-of-fresno-strong-town.html

4: http://www.theatlanticcities.com/jobs-and-economy/2012/03/simple-math-can-save-cities-bankruptcy/1629/

Great stuff, but not quite what I was wishing for. What I’d like to understand better is how on earth the assessors/appraisers (I’m not clear on the difference) tease out the value of improvements versus underlying land. This seems like the most important methodology required for a good land tax like the one described in these links.

Interesting take away from the last map is how the interstates define the left and right bounds of the most desirable places to live and work. Look like urban barriers to me, and a good argument for trench and cap.

Sad to see my local neighborhoods (Brentwood-Darlington and Mt.Scott-Arleta) are gaping holes in all of these maps. (Foster-Powell is not much better).

The city was all too glad to gobble up some of these areas for annexation and collect the tax base, but has the area gotten anything for it?

Well, with transit use down by 4% this year, and bike commuting stuck at 6% of mode share, it appears that there is only so much the city can accomplish in terms of micro-managing our transport choices, even in

crowed & tense inner SE.

A serious question: who on the blog thinks that gov’t has limited ability to influence on our lifestyle choices? There are few successful campaigns to change behavior (Don”t Mess with Texas reduced littering, MADD reduced drunk driving) but think of all the public health warnings that are ignored. I think that this focus on us, the 6% who commute by bike, is not working that well. And, unlike smoking, people don’t see their Priuses as evil.

People want to stop smoking- but they don’t want to give up cars.

“they don’t want to give up cars.”

Well actually quite a few are. Census data (2000, 2010) reveal this, and Michael Anderson knows as much or more about this than anyone.

But, sure, most are quite content to hold onto their car… only from my cold dead hands…. But I’m not particularly concerned about that. They’ll change their mind when the time comes.

“who on the blog thinks that gov’t has limited ability to influence on our lifestyle choices?”

Are you including mode choice in this category? I think there are at least two dimensions of this.

Could government, with different priorities, have a (significant) effect? Yes

Does our government, currently, the way it approaches mode choice, have a (significant) effect. Barely

Let’s stop:

– subsidizing sprawl,

– incentivizing car use,

– providing free parking,

– requiring development patterns that presume (universal) car ownership,

– fighting wars over oil,

– providing billions of dollars in subsidies to the oil and gas industry,

– and the list is endless.

If we would actually *encourage* the kinds of transport behavior that is fun, healthy, cheap, and has a future, rather than subsidizing the opposite, well, then we could do anything, expect big returns.

The most interesting areas are those that match up on 2 of the maps, but not all 3. The Foster/Powell area in SE Portland stands out as an area with lots of destinations in the 20 minute neighborhood scheme, but poor connectivity for walking and bikes.

The neighborhoods along Foster have great potential, if we have the political will to improve the infrastructure by adding sidewalks and bike routes.

The other areas that stand out are Montivilla in NE and Woodstock in SE. Both have lots of local businesses, a street grid and (some) sidewalks, but lack north-south bikeways. Fortunately, there are plans to fix this with the 20’s, 50’s and 70’s bikeways projects.

Foster-Powell at Mt. Scott-Arleta stand out to me as not quite accurate on the top map. The streets are not a square grid, but they are most definitely connected (just in a zig-zag fashion). 99% of the streets have sidewalks.

As a pedestrian, I think they work pretty well, if only because it keeps the car volumes much lower. But they are a total mess by bicycle, which is why the Foster bikeway is so important.

Perhaps the City is classifiying the alleys in FoPo east of 62nd as “streets” and that’s throwing off the average sidewalk percentage in FoPo as a whole.

Foster Powell has jack shacks at 52nd & Foster. Then there are a few cool places (Piper, Bar Carlo) and lots of new marijuana businesses. Let’s get real. The place will stay slummy for a while.

I was laughing at the business on lower Foster, but meant no disrespect to the folks fixing up those cute houses. FoPo has strengths as a residential neighborhood. Join me in kicking over the A-signs in front of the jack shacks as you ride by on your bike 😉 The PDC is worthless when it comes to what we really need- no sex industry selling girls in school girl costumes.

Something that is missing from these maps is the bike and walking friendliness of the major commercial streets. It’s great if there are tons of businesses in a 1 mile radius. But if they are all located on auto-oriented streets, like NE Sandy (Hollywood), SE Woodstock (Woodstock), NE Glisan or SE Stark (Montavilla), then people may not feel comfortable walking or biking there.

i wouldn’t classify Woodstock as a “auto-oriented” street. It’s a three lane street with lots of pedestrian crossings and islands. I bike and walk down it a good bit and don’t ever feel particularly threatened, as the street is 25 mph speed limit and most cars pretty conscious of their surroundings.

I would classify Woodstock as auto-oriented if traveling east-west. Experiences riding on Woodstock vary with the rider and the time of day – I lived in Brentwood-Darlington for 2 years and commuted daily through Woodstock, and I definitely avoided riding *on* Woodstock at certain times during the weekday. A lot of the streets in that neighborhood have no sidewalks, and/or are unpaved and muddy in the winter (a very few are nearly impassable in winter due to thick, deep mud)

I liked Woodstock a lot, but sometimes the traffic was a real pain, and climbing up the hill from Reed was frequently a chore no matter which route I selected.

One thing I do like is that the 50s bikeway will address a number of issues in the area, and provide a lot more connectivity.

…actually the cut off date for residential neighbourhoods should be even earlier than 1960 perhaps…1910 for the platting and 1920 for the sidewalks that filled in the links once the intersections / trolley stops where laid and paved.

…I am still being “moderated”

It would not take as much investment as one would think to connect up a half-mile residential greenway grid network even in these “gaps” west of I 205 to complement East Portland in Motion. We have been arguing this at https://www.facebook.com/COPINGWithBikes for a while now.

These are our public maps including a master from the river out to the city limits east, our half-mile greenway grid network when fully completed between the river and I 205, the 2030 Masterplan for comparison to show the gaps in conductivity, the possibilities for the 20’s bikeway and one focusing specifically on sidewalk and pedestrian improvements. It is really stunning how these maps line up with the city ones.

http://a.tiles.mapbox.com/v3/coping-with-bikes/maps.html

For the cost if one-half the Helvitia I 26 interchange (about 22 million) we could connect up the half-mile greenway grid west of I 205 if targeted multi-use-path connections through gravel roads were built. Sidewalk infill on at least one side of the road, traffic calming, and full safe intersection redesign would double the cost or more, but these improvements could be done over time.

This master includes sidewalk infill and East Portland in Motion once fully built out. The red are gravel road connections (or planned but unfunded multi-use-paths and overpasses) and orange are straight forward multi-use paths.

http://a.tiles.mapbox.com/v3/coping-with-bikes.map-kd30zyrz/page.html#12/45.5239/-122.6418

Even in South central Portland, 64th-65th-67th could cheaply be turned into a Salmon or Tillamook level of quality Greenway now than the Division road diet is striped for only an initial cost of about $80,000 in signs, sharrows and crosswalks. This is our “Greenway of the Week” that was posted this morning. There are a lot of other routes that could be striped and signed for very little and which have a huge initial impact.

We just need to organize.

Jonathan wrote:

“Without a massive surge of political will…”

Question for Jonathan and others — what would a “surge of political will” look like? If there were 200 people reading this blog who care deeply about this and they could all spend 30 minutes this month trying to bring the “green” to East Portland the the West Hills, what actions would you recommend?

I’ve tried to understand the Comprehensive Plan Update for 2 years. I spent 2 hours reading about it at one point, but still couldn’t get a firm understanding of the scope, the process, or the most effective way to share my opinion.

Thanks in advance,

Ted Buehler

That is my biggest problem with this map. It’s a great improvement over traditional paper plans for sharing information, but it isn’t very good at accepting comments geographically. How can we best share our thoughts on this?

Interesting that you lump all these areas together as “far out”. We live in the Hillsdale neighborhood of SW Portland. We are 3 miles away from OHSU (the biggest employer in town) and 5 miles from downtown (via winding Terwilliger, probably less via Barbur). We moved here specifically because it was close-in and we could bike to our employers OHSU and PSU. You can see that Hillsdale does well in the 20-minute category but is off the map for connectivity. There would be a huge potential for increased biking if we could improve just a few major arteries for biking, such as Barbur, Beaverton-Hillsdale, Capitol Hwy and Vermont. The problem is that the city has so far only tackled the “low hanging (cheap) fruit by creating neighborhood greenways in the closer in east side. Improving things in SW Portland requires much more ressources. Not only do we have almost no sidewalks, but tons of gravelroads and the heavy clay soil and topography makes run-off an expensive problem. So to improve things here we need a lot of political will and money. But this is an increasing urban area, not the suburbs of the 50ies anymore and should be treated as such.

Hey, Barbara, thanks for the great thoughts. If this comment is directed at the post itself, my intent might not have been clear: I said “further out” but not “far out” — I definitely wouldn’t define Hillsdale as “far out.” But as you say, the common challenge for much of Hillsdale and most of East Portland is the suburban-style, poorly connected development pattern.

Hillsdale is definitely “further out” if riding from downtown. Perhaps not in terms of distance, but definitely in terms of time and effort. I can make it to 82nd Avenue from downtown Portland in less time than Hillsdale due to all the hills.

Not that it has a bearing on Hillsdale residents – they certainly need better connectivity and safer streets. On the east side out to 82nd, there are several safe routes for me to travel – it’s definitely time we started putting more investment outside the core and started improving conditions “further out”. On the west side, “out” is a lot closer *in* than it is on the east side.

Places like Hillsdale and Multnomah Village that are forever constrained by topography really need a high-quality transit option to make them more accessible. Something like a MAX tunnel.

BPS spokeswoman Eden Dabbs writes to note that if you have suggestions for the mapping tool, you can submit directly to the bureau on their website:

http://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/60988