Here in America, the most common word associated with new bikeway projects is “safety”. Deaths, injuries, and collision statistics are the key driver of which projects rise to the top of funding lists. Want a new bike path on a street in your neighborhood? The first thing PBOT will do is check the database for reported collisions along the route.

But what if all these discussion surrounding safety isn’t really where we should focus our energy? On the Green Lane Project blog this week, Michael Andersen (yes, that Michael Andersen) laid out the following case in a post titled, What if bike comfort is more important than bike safety?:

“What if bike [project] designers, instead of arguing about safety – an argument that, to be clear, I think protected bike lanes would win – decided that the most important measure of a good bikeway is whether people tend to like it?…

But when professionals make safety their only absolute value, they presume that physical safety is the most important value in people’s lives. And that assumption is demonstrably false. Of course people want safety. But they want other things, too.

A restaurant doesn’t measure its success by the percentage of people who dine there without getting sick. It measures success by the number of people who come in the door…”

Andersen’s perspective jibes with much of what a Portland delegation (which I was a part of) learned on a recent trip to the Netherlands (which was sponsored by the Green Lane Project). That is, “safety” as an engineering/organizing principle takes a back seat to many other attributes in the development of a successful bicycle network.

In fact, one of our guides on the trip, Tom Godefrooij of the Dutch Cycling Embassy, addressed this specific idea during a presentation he gave on our first day in Utrecht. Godefrooij explained that from the Dutch perspective, safety plays only a minor part in their approach to improving cycling. On this topic, he shared one of the most memorable quotes of our entire trip:

“Safety is not a goal of cycling policy, it’s a pre-condition.”

What Godefrooij was getting at is that the Dutch don’t sell cycling or cycling infrastructure by talking up safety benefits. There’s much more to it than that. “The challenge,” said Godefrooij, “Is to make cycling convenient and practical.”

In a slide, Godefrooij shared the four basic principles of bicycle planning in the Netherlands. On top of the list was “coherence of the network” (signage, and so on), then “directness” (minimizing delays and detours), then “attractiveness”, and at the bottom of the list was “safety”.

Furthering Godefrooij’s point was Bas Govers, a bicycle planning consultant with Goudappel Coffeng. He shared their work on the need for attractive roads that encourage cycling. In a survey of people doing errands by bike on a particular route in Utrecht, Govers said 82% chose a longer — yet more attractive — route for their trip. What’s most interesting however, is when asked about their choice, survey respondents actually thought the road was shorter. “Attractive roads shorten time awareness,” Govers said, “People think it’s faster, but it’s not.”

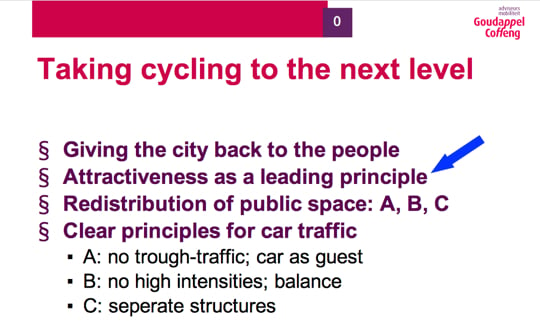

Given that, it should come as no surprise that when it comes to “Taking cycling to the next level” (the title of the Gover’s slide below), Govers doesn’t mention safety at all:

Perhaps a local example of this phenomenon is the Morrison Bridge. After waiting many years for bike access improvements, the County finally finished a $1.9 project in 2010. The new facility is definitely safer for bicycling, but it’s horrible from a connectivity standpoint and therefore it’s not an attractive cycle route. And the result? It has very low usage numbers and is therefore by some measure, a failed project.

Andersen’s blog post about safety and these examples from the Netherlands show quite clearly that there’s another, more appealing way to talk about and implement cycling infrastructure than always harping on safety.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Jonathan – yes, these are all critical items that the Dutch do well from a planning and engineering standpoint…part of why our transportation culture’s methodology has “safety” as a much higher weighting in project prioritization is that there is much less societal AND professional support for bicycling as a transportation mode and for the changes to our urban realm that such would require. This becomes clear when bike facilities are dropped (ended) at intersections because it would require physical space be taken from motorized traffic [when right of way is limited/ budget is limited] and thus effect motorized “capacity” / “level of service”.

And related to this is our engineering/ institutional bias to speak of traffic “safety” when motorized facilities are proposed / designed but it really is “capacity” as safety is #3 on the list in priority. This arises when project engineers are not willing to remove on-street parking for bike lanes (improved safety) but if an second turn lane for motorized traffic is needed then parking is removed and often with less public process than if a bike lane had caused the lane configuration change.

“…project engineers are not willing to remove on-street parking for bike lanes (improved safety) but if an second turn lane for motorized traffic is needed then parking is removed…”

This is what makes me mad. Autos uber alles!

“In a survey of people doing errands by bike on a particular route in Utrecht, Govers said 82% chose a longer — yet more attractive — route for their trip.”

This statement makes more sense when one considers that the average cycling trip distance in the Netherlands is about a mile.

I would imagine your average Portland bike commuter is riding several times farther than that.

Don’t just measure commutes, but measure all trips. I am sure Portland’s commutes are longer and trips longer than in the Netherlands… because the biking populace is filled with hard core/fearless bikers. In the Netherlands, the biking population is just the population.

I am neither fearless nor hard core. I am just a person who uses a bike as their primary mode of transport.

I don’t doubt that you’re not fearless or hard core but you read a blog about cycling politics/infrastructure, make several comments on this blog, and cycle despite the ubiquitous presence of cycling infrastructure.

Lake McTighe mentioned a three-mile standard for the Metro Active Transportation Plan in her presentation yesterday at City Hall. It seems to me that the more density we encourage around the various town centers in the region, the more likely it becomes that a given resident can get most everyday things done within a three-mile radius of home. Convenient and attractive (and safe) bike infrastructure is a part of the vision for encouraging that increased density inside the UGB.

Definitely interesting way to look at things. It makes a lot of sense- you make things easier and practical- more people will use it. Bike-share is a prime example of this. You make easy, practical and convenient- people use it. If it’s safe but inconvenient- no one is going to use it.

Couple things: We are a different country, different culture–cyclists in the US have to be part combat pilot as we are navigating a generally hostile environment. Also, and this gets into a co-fetish, that of dressing like a “normal person” (whatever the hell that is) we have less flat terrain and longer commute and errand distances. Please, please, get over your “delusions of Amsterdam” as another poster on this site has called them.

As a guy with an Indian name used to say, be here now.

Gets old in these conversations about places where cycling is functional and part of everyday lives to always have someone say how you can’t compare to these places, how we are different because of X,Y and Z. Nonsense; many of these places (Netherlands in the 60’s, Germany in the 80’s) were as car centric and antithetical to cycling as US culture is now. Change can happen. I hear similar rationalizations as Dave’s from people in other US cites who equivocate as to why they are not Oregon and can never be. To get real and drop “delusions of Portland”. Just conceits and low horizons. Don’t be so easily stymied. Go visit and ride there and see. (or Denmark, or Germany or or or…)

Hills? Lower gears. Particularity funny when people complain about cold where they live as a reason people can’t ride – do we tell them about Minneapolis cyclists?

BTW I’ve spend many weeks cycling in The Netherlands and many people ride much longer than a mile. The elderly sometimes end up with e-bikes to combat those North Sea headwinds. Oh, and maybe if your commute is 50 miles you might want to live closer to work. Because we have set up an atomized and sprawled infrastructure is not a reason to continue it.

Soooo…how does a society go about establishing this “pre-condition” of safety so as to enable the move toward “attractiveness”? Did Godefrooij dish?

Easy. Adhere to some clear and basic planning principles that put people first. Our biggest problem in America is that car-centric planning absolutely dominates all our engineering practices and standards. We need to throw those books away and start fresh with a new approach that puts humans — not cars — at the center and works out from there.

Well, not easy — but clear. Follow-up, though: Is it ethical to go straight to the “attractiveness” angle *without* the pre-condition of safety (as defined here) having been met? WWGD? (What would Godefrooij do?)

That’s a good question… I think what the “American context” answer to this is to make sure we are keeping in mind these Dutch principles of attractiveness when prioritizing and designing our projects. And I think we have more acknowledgment from transpo leaders/politicians here that our streets are not as safe as they need to be in order to usher in the large amount of riders like we see in the NL.

It seems that here, we have a pre-conception that cycling is inherently dangerous and inconvenient. Therefore, all we can do is try to make it less dangerous for those wierdos who already do it, but we certainly don’t expect “normal” people to start biking just because there’s a new MUP in town. So, we build byzantine, disjointed, sub-par infrastructure that still requires anyone who would use it to study maps, ask their “hard-core” cycling friends, and take “practice runs” on weekends to see how it works or where it actually goes–a level of commitment that is not necessarily there for newbies wanting to try an inherently dangerous and inconvenient travel mode for the first time…

On another topic, I like the “low-stress” description for bike routes. What I don’t like is the notion of “perceived safety” if it doesn’t correlate with actual safety. I’ve found that oftentimes when I learn to do things in a way that is actually safe, suddenly it becomes much more “low-stress”.

I don’t know about other cities, but before McGinn came in the transportation department only improved streets one corpse at a time. Until somebody was killed they’d say a street was safe, no matter how fast people drive on it. Too bad it doesn’t matter how enlightened your mayor is when the public cares more about free street parking than saving lives.

It’s the same in Portland. Everyone knew Glisan was dangerous before Heather Fitzsimmons was killed. 136th Ave needed sidewalks long before the little girl was killed crossing the street.

There are pieces of bike infrastructure, or missing infrastructure, I ride through/around where I think, “someday this will be fixed when someone dies here. I hope it isn’t me.”

If only the city valued us as much in life as in death.

Is this really that bold of a statement? For one to be comfortable doing anything there has to an feeling of safety to get there.

Though I will agree and often do go out of my way, for a more scenic or quieter route. That’s part of the whole bicycle experience for me. It’s more about ride itself, definitely more so than the destination usually.

It’s all about perception. Bruce Schneier (the security expert) has written a lot about how people misjudge risk.

I agree it’s a precondition, but it’s also a side effect; both in that the things that will make a route “attractive” will often increase safety as well, and a route with more riders will have a natural safety in numbers aspect.

I think it’s a point that’s been beaten to death, but I’ll kick it one more time – the focus on safety also has the effect of highlighting the perceived danger of cycling to non-cyclists, discouraging them from riding, and therefore decreasing safety for everyone.

The Dutch have significant bike ridership across a wide range of urban, suburban and rural environments. If Netherlands were located on our coast, it would be at/around Prince Rupert, British Columbia – so Dutch weather is not always pretty.

I agree with ed. We in the USA need fewer excuses and more willingness and flexibility to learn and adapt from another countries when they are doing something better than us, certainly no less so when such countries are economically successful/highly affluent.

Washington County Commissioner Dick Schouten

And living in the large flatlands of the Tualatin Valley

The Utrecht photo: That’s what I imagine when I think of good infrastructure over I-84 . Imagine that at MLK, 28th, possibly 12th, 21st…dreams.

But when the Dutch were at risk of being overwhelmed by cars, the rallying cry was STOP MURDERING CHILDREN. They started by demanding safety; now they’ve got safety and they can go for all those other characteristics of an everyday biking network.

And as always, “road safety” is a myopic metric that only captures socially unacceptable forms of early death. Heart attack, diabetes, cancer, and stroke — all that increased risk from driving does not count. It’s been measured, and it is a big number — years of life lost, 39% higher annual mortality for car-driving commuters.

Nonetheless, if a road is made comfortable for cycling, it is probably also safer for cycling. But if a highway department claims they are doing anything at all for safety that does not involve getting people out of their cars in one way or another, then they are missing the forest for the trees.