[This is our latest Bike Science column by Shawn Small. Read previous entries here.]

In the world of singlespeeds and fixed gears you often hear people talking about each other’s “gear-inches”. This is an easy way to prove your machismo and is also a way to get useful data about your riding style. Today on Bike Science, I’ll take a closer look at gear-inches and explain why I prefer to use the concept of “gain ratio” to out-macho my friends.

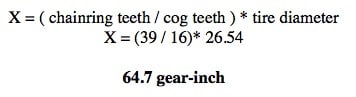

The gear-inch is calculated simply by knowing the following information:

- Number of teeth on your chainring (front gear)

- Number of teeth on your cog(s)

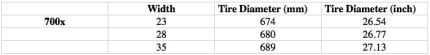

- Tire diameter in inches (see helpful chart below)

On my fixed-gear bike I run a 39 tooth chainring and 16 tooth cog on a 700×23 tire.

The gear-inch is useful to roughly know how hard or easy it is to pedal for trash talk. But it doesn’t take your crank arm length into account, which is a significant factor in determining the mechanical advantage of your drivetrain. That’s why I prefer to use the “gain ratio” developed by Sheldon Brown as a means to compare my machismo to others. (Note that it’s usually received by others with confusing looks.)

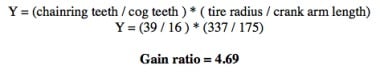

The Gain-Ratio is calculated by knowing the following information:

- Number of teeth on your chainring (front gear)

- Number of teeth on your cog(s)

- Tire radius in millimeters (see helpful chart below)

- Crank arm length in millimeters

This ratio can be used as (1 : 4.69); meaning for every inch or mm my feet pedal, the bicycle goes 4.69 inch or mm forward. (Note: Remember to avert unit disaster by using either inches or millimeters.)

With the holiday weekend upon us, perhaps you’ll have time to play with these measurements. Whether you use them to trash talk with friends or just to satisfy your inner bike scientist is up to you.

Further reading:

— Gain Ratios: A New Way to Designate Bicycle Gears, by Sheldon Brown

— Sheldon Brown’s handy Gear Calculator

— Bike Science is written by Shawn Small and is sponsored by: Strava.com – GPS cycling, virtual competitions and detailed ride analysis.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Neat!

Research seems to indicate power output stays the same regardless of crank length, go to fixedgeaer fever.com. It’s all about spinnin’ the biggest freakin’ gear you can as fast as you can.

The rare air is still reserved for those who can spin.

Who cares about the size of fixie’s gear-ratio? So long as it has a viable break, I could care less.

Marcus,

Some people do care about things like this. I value your opinion, but your comment feels sort of mean-spirited to me. I was tempted to trash it, but I’ll leave it up for now. Please take my thoughts into consideration when you leave comments in the future. Thanks.

Gee, and I though Marcus just forgot to include his <disgruntled with the cops/sarcasm> tag 🙂

Sheldon Brown the man.. tons of great into on his site

still.

Hey! That’s my bike!

(and it ain’t no stinkin’ fixed gear)

what about this forum article that states that crank length doesn’t matter? it links to this article that gives all the stats/data to show it…

personally I could care less how many teeth are on my cogs at this point… I have gears… when it gets harder/easier to pedal I shift… (:

I know, I know, that’s cheating… if it helps any I find myself rarely shifting the front anymore as I put more miles on…

How is using gears cheating? That somehow implies riding fixed gear is somehow not cheating? I don’t understand.

Spiffy, good find–however, it appears that post and article are about the overall efficiency and power of a rider on a multi-geared bicycle, where a difference in crank arm length can be counteracted by changing gears. In any setup, crank arm length is one of the few factors affecting the relationship between distance pedaled and distance traveled. That relationship is particularly relevant on a singlespeed or fixed gear bike, since shifting is not an option.

I thought that it was saying the gear was the usage, so it didn’t matter the crank length so long as it’s the correct length for your application…

and since there are so many variables in Portland urban riding I wouldn’t think that length would matter in the long run…

this is timely as i just picked up a used fixed gear. i actually have the same ratio as you, but i was thinking of going to a 14t cog which would put me at 5.6. the 16t just makes it tricky to bomb down mississippi, my normal antisocial route.

Shawn, great little article as always. My $.02: I have found that crank length has a significant effect at slower cadence when accelerating or climbing on a singlespeed mountain bike. The extra leverage of longer cranks helps you get the gear over the top. Spinning quickly is more efficient over long distances and shorter cranks make it easier to spin quickly because your feet make smaller circles. For mountain biking the terrain usually makes spinning fast for any appreciable amount of time difficult, so longer cranks can be advantageous.

Also applies to BMX racing. Generally a longer crank is used compared to MTB or road.

All a tall gear proves is that are willing to destroy your knees for bragging rights. it will eventually catch up to you.

I prefer a low gear and a lot of spin, but the majority of my “cycling” background is BMX.

What it’s really all about is your preference not what anyone else thinks of it.

if you spin a 53-11 at 100 rpm your knees will be fine and you will get from point A to point B fast, very fast.

you first have to get up to speed from a dead stop, and then you have to bring it down at the end. both these transitions are hard on the knees.

if you are shifting correctly (e.g. often) there should be little resistance on the up and down stroke. (this also assumes that you are clipped in.)

i also often use my 53-11 going down hill. 😉

sorry, i thought we were talking about fixed gears

…lead to people who choose a crap ratio blowing lights and pretending it makes them cowboys, assassins, or whatever’s hip ‘n’ “manly” this year. 😉

p.s. how do I get the cute little picture “avatar” in the commetns

http://en.gravatar.com/

tada! have fun.

Testing mine…. awww yeah.

@Spiffy @steve Brown

There is a lot of conflicting evidence with regard to crank arm length vs power output. But power is dependent on the input cadence and the rider.

The “gain ratio” is a unit less number of just your equipment and is unaffected by rider/cadence or any inputs.

@Tony

Great recommendations and I certainly agree, I still play around a lot with different cranks/gear combinations for my CX and MTB (probably too much)

If only I could find the combination to beat you at Short Track.

I agree with Tony on his point about using long crank arms for SS MTB’s. Winter is when I switch over 100% to using my Single Speed.

Shawn, I agree with Tony the long cranks on the SSMTB, but what do you guys think about shorter cranks on the SS cross bike?

The usefulness of Gain Ratio is one of the few things on which I’ve disagreed with Sheldon over the years. Yes, it is an overall measure of leverage, but crank length and gear inches contribute to leverage in different ways and this lumps them together.

I’ve always preferred a slightly longer crankarm for mountain biking and a little shorter for pavement work. Overall Gain Ratio being equal, I’ll take a slightly longer crankarm with a slightly taller gear ratio to grind my way up a steep climb. And I’ll take a slightly shorter crankarm with a slightly shorter gear ratio for the road, because shorter cranks are easier to spin.

Crank-length alone really is not much better than a gear-inch figure, for it does not account for lengths and angles of a rider seated on a frame and saddle.

Any crank-drive mechanical system (technically a gyrator) is a four-bar linkage, of which the crank arm is but one link. The other three are length from knee joint to axle of pedal, length from hip joint to knee joint, length from hip joint to crank spindle. How all these affect developed torque was made clear by Archibald Sharp in his book, “Bicycles & Tricycles, a Classic Treatise on Their Design and Construction,” way back in 1896. Amazing that Sharp’s method has been ignored by modern gurus!

Sharp, a superb mechanical engineer, applied the sophisticated mathematical physics of the Irishman William Rowan Hamilton, who had invented the concept of the hodograph, representing constrained mechanical systems as plots of their speed. In the case of human anatomy driving a bicycle Sharp “figured” speed of the knee and showed that it is the same figure as force applied to the crank. Force times length is torque. The hodograph shows force, and hence torque, at any instant, but the area bounded by that figure is the full torque developed over the complete down stroke of each pedal. It is this that moves the bike.

See page 28 and page 268 in Sharp. Measure your own anatomy, your bike set-up, and calculate your own hodograph. It is tedious, but not so difficult. All the lengths count. It is the only method that gives the complete answer for any cyclist.

And the tooth-ratio of chain-ring to cog constitutes a mechanical step-up transformer after the mechanical gyrator. It is the simple part of the drive system: a transformed gyrator.

The reader comments here are feeling a lot like OregonLive. Post a story about sports or macho gears and the comments flow like testosterone in a high school.

Because machismo and masculinity are such bad things. Some men are MEN.

I don’t see any ignorant hate going on here, so it is nothing like OregonLive.

man, 65 gear inches is a little too spinny for city work. 69-74ish gets you a reasonable top speed and still lets you get off the line at a light without giving yourself a hernia. Of course, I suppose one can get used to anything: I rode a 42/17 for a while at around 65 gear inches and it wasn’t that much easier up hills, and it was a little too small on the flats, which is most of PDX.

For all you cats riding small front chainrings:

Try a larger chainring and a bigger cog (42/17 is about the same as 39/16 etc…) and see if you get longer wear from your equipment.

Next math problem: Calculate Skid patches, and tell me why you keep wearing out tires while rocking your (oh so manly) 48/16.

Thanks for this great article. I had found internet info on gear-inches, but I never knew how the length of the crank arm would work into the calculation.

I’m more interested in riding around town from A to B. Speed is not too important, but relative ease of pedalling, especially on uphills into the wind with a load, is.

I bought a new town bike about a year ago. I also have an old 10-speed I use to put miles on and a 3-speed I use for errands (which I wanted to replace with the town bike). I used the gear-inch calculation on my two existing bikes to make decisions about my new bike.

I don’t care a lot about the high gear – I’ll coast down hills. But I care enormously about the low gear – I’d better be in some extremely difficult situation if I need to shift into first.

As a result of my calculations, I confidently had the bike shop install a larger rear cog with more teeth (that drives an internal 8-speed hub). I am very happy with this choice.

I feel it is for making this sort of decision that knowing the contents of this article are valuable. It won’t be of great use for someone’s first bicycle, but once you learn what you like and don’t like about your gearing, it will be of enormous value for acquiring your second bicycle and beyond.