Many of us can summon a general outline of Portland’s streetcar legacy. We know the city was once filled with tracks and lines that criss-crossed both sides of the Willamette and we have experience seeing old tracks on or under a street we ride on. But for transit buff Cameron Booth, it is a history that deserves to be understood in greater detail. Booth, whose fascination with public transit maps began after a boyhood ride on the London’s “Tube”, is a graphic artist by day who’s working on a project to digitize Portland’s streetcar history.

Some of you might know Booth as the guy behind Transit Maps, the very popular blog and online store that features nearly 200 vintage and artistic transit maps from all over the world — including the BikePortland collab, “1896 Cyclists Road Map of Portland.” Booth enjoys restoring old transit maps and creating his own. A few months ago, he mentioned to me in passing that he was researching streetcar information via historical articles in The Oregonian and then sharing what he learned on a website. I’ve always been fascinated by how streetcars have shaped our city, so I was instantly intrigued by the project. This morning I finally got to learn more about it.

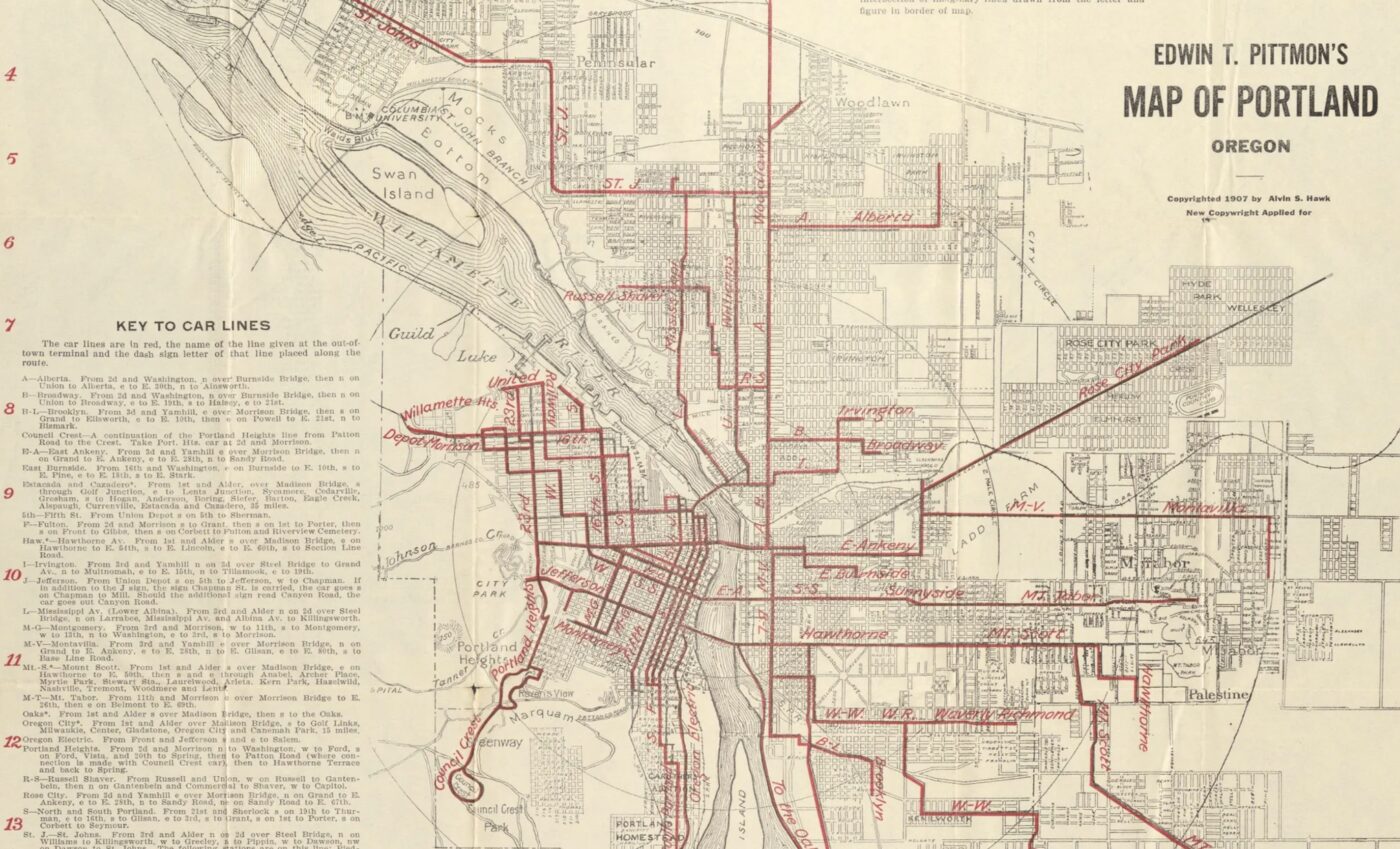

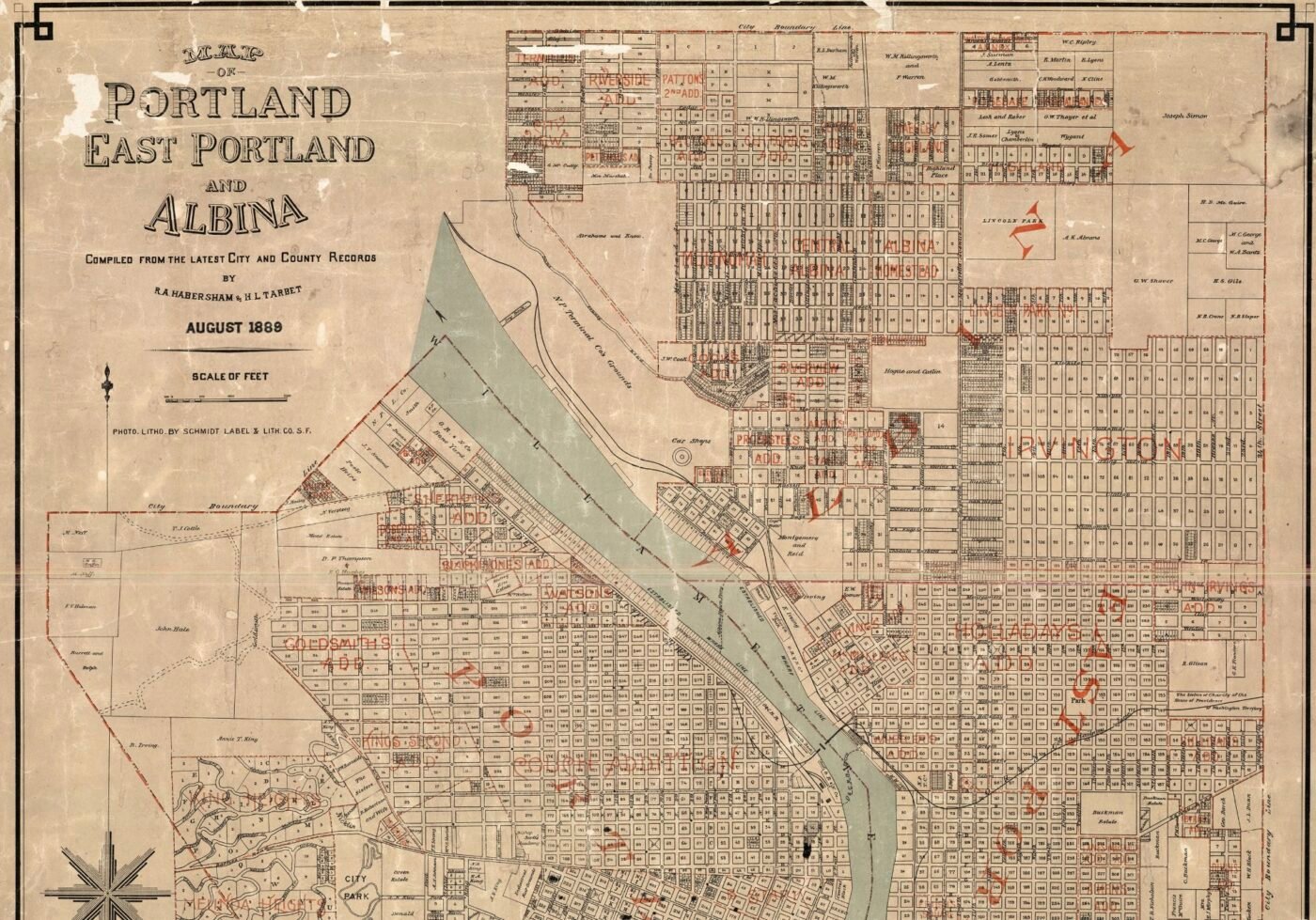

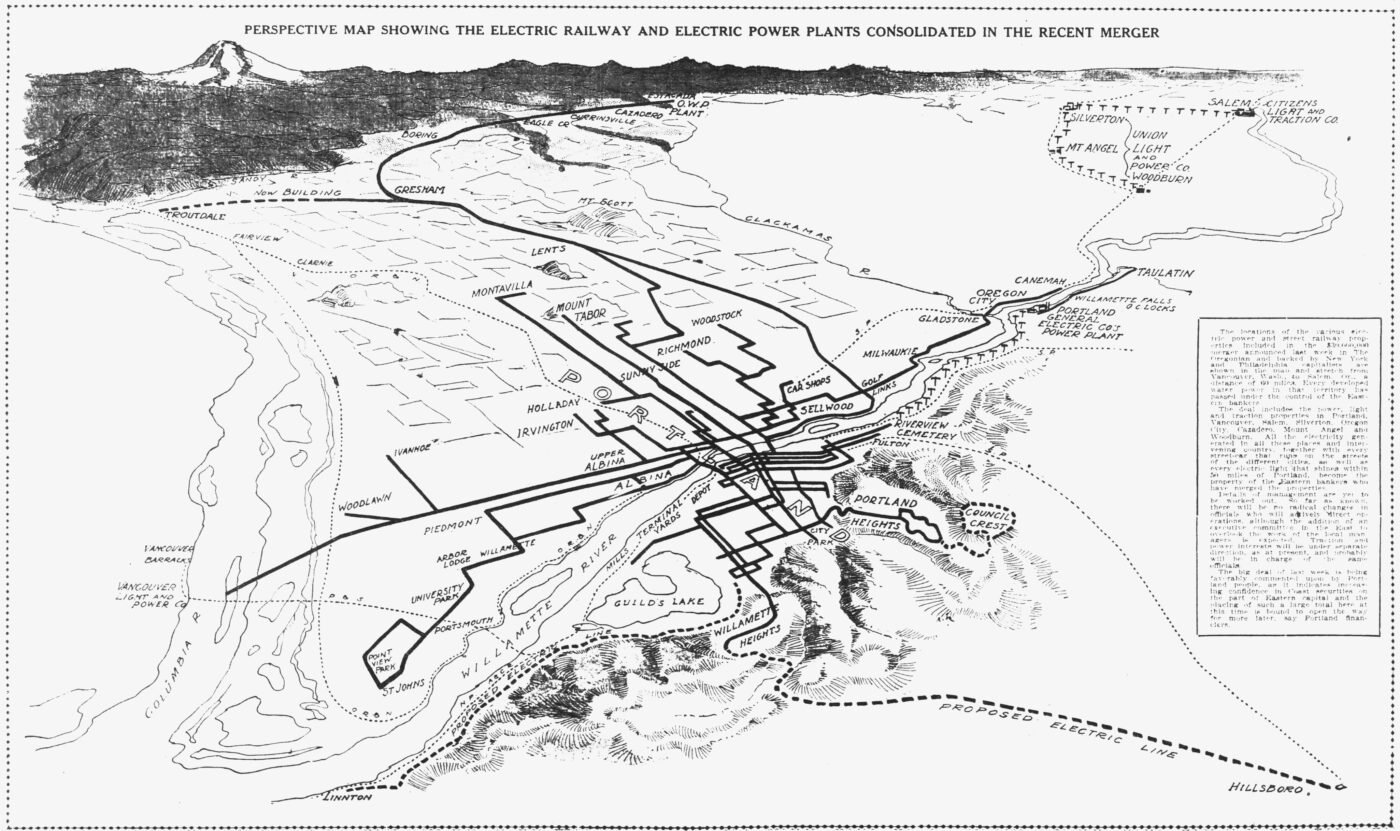

Portland Streetcar History is a website where Booth is sharing the over 1,000 articles he’s transcribed so far. He’s sharing illustrations of old maps and has compiled information on 35 different streetcar companies and 68 distinct streetcar lines. He began the project in February 2024, armed with nothing more than a Multnomah County Library Card and an insatiable curiosity. The project started because he was already doing the research for this map projects, “And every time I went to work on them,” he told me in an interview this morning, “I have to go the library and borrow like eight different books, or I have to look on the Internet and find four or five different websites to get that information that I’m after. So in the end, I guess I was just like, well, what if I just started compiling all this stuff myself?”

Judging from the changelog on the wiki-style website he’s using to share everything he finds, Booth edits a few articles a day. Browse the list, choose something to click on, and you might find an article from June 19, 1904 that details a new “through line to St. Johns” that would have created a new route, “from the heart of Portland” all the way up the peninsula to St. Johns. Or you might click on a detailed, high-resolution image of a 1932 map of transit lines in the central city. Each item is notated by Booth with updates and insights, creating an intriguing trove of transit information.

What started as a way for Booth to fact-check specific route locations and line information, has grown into a project that tells a wider story. Through all the articles he’s transcribed, Booth says, “You can see the social impact and the way that the streetcar basically, in a lot a lot of ways, defined the way Portland looks now. You know, all the cool neighborhoods are all along the old streetcar lines.” It makes you wonder what those neighborhoods were like in the peak of Portland’s streetcar era, which Booth pins to 1915-1920.

Beyond that, Booth said he’s learned of a brief revival during World War II. “There was shortages of gas and tires and stuff like that, so they actually dug out one of the streetcar lines. They’d buried it in 1940 and then there was a rubber shortage for tires so they basically dug up this old line and started running streetcars on it again.” It was the Bridge Transfer line that ran from the Broadway Bridge to the Hawthorne Bridge on Grand and Union (not Martin Luther King Jr Blvd) on the eastside. “There’s photos in the newspapers of them jack-hammering out the tracks,” Booth said.

The tracks would all be buried eventually as rising maintenance costs and stagnant rider fares buried streetcar companies in debt. Booth says from what he’s gathered in contemporary news articles, it was not the onslaught of cars or any conspiracy by Big Auto to buy up companies and bankrupt them. They just weren’t cool anymore. “By the 1930s, they were seen as old-fashioned and out-of-date,” he said. Unloved and unmaintained, the streetcars were replaced by buses which were considered to be much more modern and comfortable.

“And you can literally see the attitude change to streetcars through the newspaper articles,” Booth shared. “At the beginning it’s all, ‘Oh my goodness, another streetcar line! How exciting!’ And by the end, it’s like, ‘Thank goodness that’s gone.’ The public attitude towards them was changing drastically.”

Has Booth come across any mentions of bicycle riders in his research? Yep. He recalled two stories.

In 1890 or so he came across an article about a man who was biking on SW Jefferson near the old Portland Heights cable car line. The man fell into the hole where the cable returned and was seriously injured. “He wanted to sue the cable car company, but they said, ‘Well, you were riding a dangerous and defective bicycle.'” Booth also said around the turn of the 19th century, when American was solidly in its bicycle craze era, streetcar companies lamented that they were losing ridership to bike riders.

Booth’s research is full of fun little nuggets like that. And it’s all available online. Check out his Portland Streetcar History website to learn more. And if you’re looking for an excellent holiday gift, check out his store on Transit Maps.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

These maps and documents are awesome!

https://www.opb.org/television/programs/oregonexperience/article/streetcar-city/

Very cool BC. It wasn’t till somewhat recently that I realized part of the reason the Springwater/Cazadero trail exists is because the trestle over the north fork deep creek burned down, basically making that system useless up to Boring. But trains/trolleys were well on their way out because of cultural decisions already.

On February 22, 1950 my father took me on one of the last runs of the Council Crest streetcar. The photo shows me standing on the steps of the car. I was not quite 4 y.o.

That too is awesome!

Amazing! Do you remember it?

I actually do remember the ride. It was just 4 days before the Council Crest streetcar had it’s last run on Feb 26, 1950. My dad was a rail fan. His dad was a streetcar conductor in the late 20s and early 30s. I remember my grandfather taking me on other streetcar rides.

This is cool Pete and it gets to a somewhat both exciting and depressing point I feel about former rail systems. There is so much potential! Various uses for these massive undertakings (entire mountains have been moved to create berms and trestles, for example, the Paulinskill Viaduct) exist (e.g., recreational rail biking, rails-to-trails, the reintroduction of rail lines etc).

The reason we do not have a non toy train from Portland to LO is because rich people don’t want it. It’s the “crime train” scenario that’s played out like when the Milwaukie MAX line was built. The reason we do not have the Yamelas rail trail was a result of an ideological backlash. Rail trails are a lucrative business, I mean, very very lucrative (e.g., GAP trail). But they COULD also serve a transportation function, were it ever a priority to our culture/government (in MA it has become one).

Two projects that SWTrails has been working on for years, the Hi-LO Trail (Hillsdale to Lake Oswego) and the Red Electric Trail show that there is public interest for active-transportation trunk routes between towns. Those two trails were supported by the State of Oregon with federal Coronavirus grants, and Parks and PBOT have also contributed to the efforts.

But it is an uphill battle. Both non-profit and government money is focused on historically underserved communities, and even though I make a pretty good case that the RET would serve the active-transportation needs of the many persons who live in affordable housing units along the route, I can’t seem to catch a break with funding.

It’s frustrating. I don’t think Earth’s atmosphere cares which neighborhood the carbon comes from, but this whole area of town is, by city policy, being forced to remain in cars. Soon, we’ll hear about those selfish, uncooperative rich-folk in the southwest who insist on driving everywhere, and who have caused global warming. (Meanwhile, our bus routes have been slashed, we can’t get sidewalks or bike lanes built . . .)

All you fancy SW Portlanders with your PCC campuses and hills and your dairies 🙂

I remember living near Capitol Hwy not too far from the village, and trying to figure out how to get to PCC for classes. I gave up, got a car and drove.

Don Baack calls Hillsdale “the Jewish Alps.” I never realized how historically accurate that was until I recently began writing up some history of the area for the Hi-LO trail. Those rolling hills were divided into dairy farms owned by Swiss-German dairy families who immigrated from Alpine regions.

And the Jewish community relocated to Hillsdale after the urban renewal of Lair Hill/ south downtown forced the mass exodus of Jews, Italians, Roma and others living in these working class neighborhoods.

It just wasn’t that long ago.

If I was a neighborhood leader in SW, I’d try to convince city leadership that poorer Portland residents need to pass through SW in order to get to the better-paying hi-tech jobs in Washington County, and that an entirely off-street railroad-grade path like the Red-Electric is quite worthy of the type of equity funding being spent in East Portland, but it would have to be part of a cross-town network that presumably includes the Springwater and Sullivan’s Gulch trails, or else (or in addition to) an equivalent curb-protected bike lane route. At some point you’ll need a “reputable” study to support such a finding followed by research by the planning department (whateveritscallednow).

Thank you David, those are good insights and I’ve been thinking along those lines myself.

Here’s a Portland urban planning conundrum: there has been an abundance of residential development in east Portland, because it is a relatively inexpensive, easy place to build. But the good jobs (those that offer health insurance and retirement benefits) are mostly on the west side. (It was a stronger case to make 5 years ago before both Intel and OHSU began having troubles, but still.) So that sets up a transportation quagmire.

At the same time, there has been an opportunity cost to suppressing densification of SW through infrastructure inadequacies. No one at the city talks about return on investment. The ROI in SW I would think would be high.

But that conversation doesn’t happen amidst the jockeying over moral high ground that accompanies identitarian politics.

I’ve always been surprised that with the high-density office complex on Pill Hill and the apartments on the hill overlooking Goose Hollow that there aren’t a lot more high-rise apartment clusters all over the SW Hills. From a runoff, nice views, and FAR point of view, it would make a lot more sense to have 40-story apartment buildings like those in Arlington VA or Vancouver BC and convert the surrounding SFR to open-space parklands and bioswales, and connect everything with a DC-like Silver Line combo of subway and skytrain. And as you say, SW is stuck between two major employment centers, hi-tech to the west and office/medical to the east, so an ideal location for high-density residential.

About the PBOT map of historic trolley lines, Booth’s comment, “…though it may just be a conglomerate map of known infrastructure…” is spot on.

Back in 2000-2005 I was part of the team of staff and interns who mapped Portland’s “street features” from old linen maps on fire-resistant asbestos boards, all of which were drafted by hand rather than printed from about the 1920s through the 1960s (complete with eraser marks), some of which had water and mold damage from poor storage locations – these were working maps that were updated as needed over a 50+ year period, on the same original very colorful maps. Among the details were curbs, sidewalks, rails under concrete and asphalt, light posts, signals, and so on, plus dimensions of where everything was relative to everything else. The old maps covered the city boundaries up to about 1960, then we used paper maps for the part of the city boundaries through 1986, and Multnomah County “as designs” on microfiche for the 1986-1992 annexed areas.

The maps were redrawn using Microstation MGE (a very sophisticated CAD) set up by Bob Goldie at PBOT (he later moved on to the city IT bureau and is likely retired by now), then later converted to ArcGIS and ArcMap and given attributes. We used the Multnomah County cadastral (property line) maps as our base. I can’t remember the projection we used. Kevin York at PBOT would be the best person to contact about this project.

David – this is astounding information. Thank you! Everyone I’ve ever talked to – including a few PBOT people! – has just told me that no-one knows who converted the original engineering drawings to GIS, but they’re all very grateful that it exists when they have to go digging roads up. I’ll add this information to the page about the GIS map.

To be sure, I was just one of the interns, but we did put in so many layers of data, each with different attributes, that it would be simply be a matter of consulting the GIS metadata catalog to find the relevant layer, then extract all the linework related to that layer. If you look closely, there are lots of measuring lines with arrows, so likely the next data layer has all the dimension text in between the measuring lines, and that missing layer only has text for the trolley line data, it’s how we did things in the CAD process. It’s about 90% likely Bob himself extracted the trolley layer in around 2002 or so, but it could have been one of his underlings who did it (he had 4 other staff plus 4-6 interns.) I remember there being at least 50 data layers.

Yeah folks who dis on david for interrupting our comments all the way from NC, please consider how much perspective he’s got to offer with this kind of stuff.

Thanks for sharing this! I’ve used his website more times than I can count to figure out assorted transit esoterica in Portland – such a cool project!!

Do we have any additional info on the Montgomery streetcar extension? That turn onto NW 23rd seems like a potential issue, and traffic on 23rd is definitely going to be an issue.

They’ll probably figure it out – and usually the car traffic on NW 23rd is only bad closer to Burnside.

My big issue with the streetcar extension is the fact that it will be using battery streetcars. Womp womp. At that point just buy TriMet some more battery buses and beef up service on the 15.

What is the advantage of street car over a bus if they are both running on batteries, aside from the road parkour provided by the tracks? The streetcars we’re using aren’t even “cute”; they’re just noisy, slow, and cheap looking, with the bonus of providing a rough ride.

Among planners, Streetcar (and anything with open tracks) is often described as Viagra for developers – they get terribly excited about building new stuff next to the tracks, even when the actual station isn’t close by – the higher and more dense the better, and the more profitable. It’s not just in Portland, but any other US city that has it. It’s not about moving people, it never was, it’s all about urban revitalization and development, and fat profits.

NW 23rd seems pretty revitalized already.

Apparently in the 1970s NW Portland around 23rd was considered to be a slum going rapidly downhill.

Funny thing from a NYC perspective vs the tube which I’m sure have had their own culture wars vis a vis maps. People are VERY ideological about the MTA map, which has had some iterations over the years.

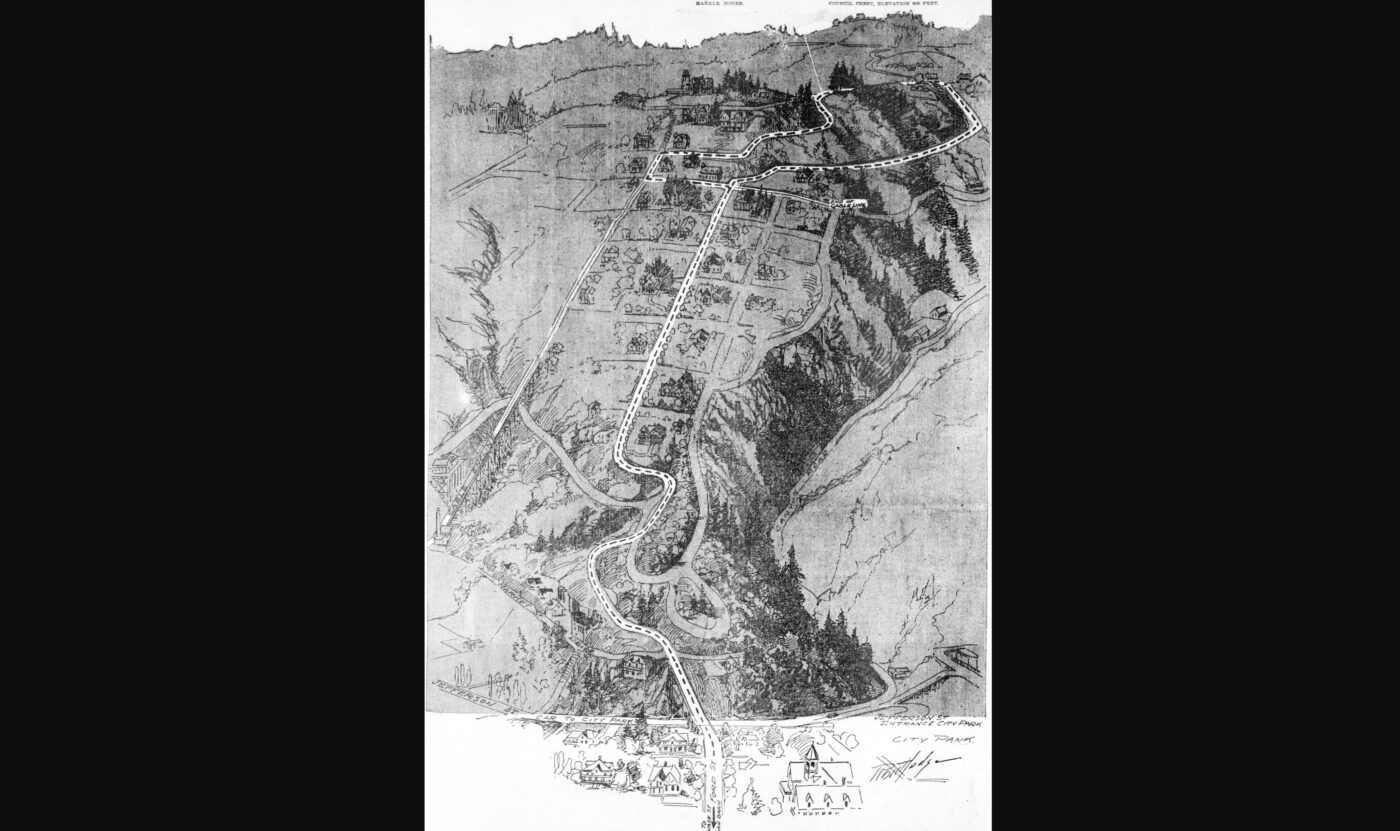

What a labor of love, thank you so much, Cameron. Reading about the Portland Heights Cable Car (there is still a Cable Street) and later the Council Crest Trolley, I find myself wondering what about the turn of the century allowed for such growth and construction. The Cable Car, for all the brouhaha, only operated for a few years, to be replaced by the trolley (which only operated for a few decades). A trolley down Vista and along 23rd — I would love to have that today.

Lisa, at the turn of the last century you were either rich enough to own a horse (and maybe a carriage of some sort – but private conveyances were expensive!) or you walked. The streetcar was massively influential in expanding Portland past that initial walkable area into the suburbs we know so well. The first horsecar line down First on the west side wasn’t fast, but it got you out of the mud!

Then, starting with Irvington in 1890, property developers used the new electric streetcar lines to get potential buyers out to their land. As the inner suburbs started filling up, the developers would move further out and the streetcar would follow. The developers either offered the streetcar companies large subsidies to build the line to a particular addition (the northern end of the Broadway line up the hill to NE 29th and Mason is a great example of this), or built the line themselves while shrewdly passing the cost of actually operating the line off to the streetcar company – the KIngs Heights, Arlington Heights and Westover lines are all examples of this type of operation.

As for the cable car, it was already pretty late for that technology by the time it got adopted here, so it got abandoned fairly quickly in favour of trolleys. The cable line was extremely expensive to maintain, as the cable wore out and had to be replaced fairly frequently.

And every city nationwide felt they had to have this newfangled system. I’ve come across numerous small towns that had under 10,000 residents in 1900 with at least two interconnected trolley rail lines, that they felt their communities were modern and progressive with such as system and no longer hick cowboy towns. In nearly all cities, there was a 30-year boom from 1885 or so to 1915 or thereabouts, then a rapid decline of the system in favor of trolley-buses, then diesel buses, with most systems getting buried in asphalt between 1925 and 1945 as local residents switched to using automobiles and buses. Both the trolley systems and the later bus systems were rarely municipal until the 1980s, most were run by private companies, even power companies, and nearly always the new bus routes would follow the old trolley line routes religiously.

This was a really fun watch/listen. Thanks for having Cameron on! It’s so cool to see little pieces of the old streetcar system poking out of the streets. It’s also really interesting to see old pictures – comparing things now to how they used to be, and imaging (maybe a bit too optimistically) what they could become.

I’ve been a fan of Cameron’s transitmap.net site for year, and am very excited about this project. Ray Delahanty (aka “CityNerd”), formerly of Portland, recently did a great YouTube video on the impact streetcars had on Portland’s current cityscape: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W6uy6Sw3P3o

I recently came across Cameron’s work on Bluesky and was blown away by his impressive collections online. His passion for local history really shines through. I also appreciated how he took the time to answer a question I had about a NW Portland intersection.

If he hasn’t already, I think it would be amazing if Cameron eventually collaborated with other local historians, like Doug Decker of Alameda Old House History. Bringing their stories together could create a richer, more connected narrative of Portland’s past.