At a time when Portland’s bike ridership numbers are falling, we can look to Denver where electric bikes are bringing new people into the fold.

House Bill 2571, a.k.a. the e-bike rebate bill, is currently working its way through the Oregon legislature with strong support from activists statewide who know just how transformative e-bikes can be for getting people out of their cars and lowering carbon emissions from the transportation sector. Now, thanks to a report released out of Denver last week, these advocates have more data to back up their stance on the efficacy of e-bike rebate programs.

After launching its wildly successful e-bike voucher program last April, the city of Denver, Colorado has become an exemplar for why it works to give people money for electric bikes. Denver’s initiative allows any resident to access a $400 e-bike voucher, while income-qualified residents can access up to $1,200, with an additional $500 for the more expensive e-cargo bikes. Every time these vouchers have been offered, Denver residents have snatched them up like hotcakes: more than 4,700 Denver residents became e-bike owners in 2022, and an additional 860 people benefited from the latest round of vouchers offered in January.

The report is co-authored by multiple organizations including the advocacy non-profits PeopleForBikes and Bicycle Colorado, sustainability research organization Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), the City and County of Denver and Portland-based ride tracking company Ride Report. Each group digs into a different pertinent topic, like how often these new e-bike owners are using their bikes, what kinds of trips they use them for and how other cities and states should create their own e-bike rebate programs. Here are a few key insights gleaned from the report.

People use their electric bikes as car replacements

Although many people who own electric bikes can tell you how life-changing they are for getting around without a car, some e-bike rebate skeptics have expressed concern that people will use public funding to buy bikes they never use. The Denver report refutes this idea, showing data that suggests people use their new electric bikes a lot.

The City of Denver’s office of Climate Action, Sustainability & Resiliency (CASR) sent out a survey to rebate recipients to gauge some of their travel habits. Through the roughly 1,000 people responded to the survey, CASR gleaned that respondents are riding their e-bikes an average of 26 miles each week, replacing 3.4 car round trips. In total, CASR estimates the new e-bikes replace 100,000 vehicle miles traveled each week.

Additionally, Ride Report has been studying data from a smaller pool of Denver e-bike rebate recipients who used their ride tracking app to record how they used their new e-bikes. Ride Report wanted to know if “rebate recipients actually ride their new ebikes” or if they “sit dormant in the garage collecting dust,” and their findings indicate the former result. 65% of e-bike rebate recipients who downloaded the Ride App were riding their e-bike daily, and 90% were riding weekly.

Interestingly, the report indicates that income-qualified residents use their e-bikes nearly 50% more than standard voucher recipients, perhaps because they didn’t have a reliable transportation method before getting their electric bikes. Oregon’s proposed e-bike bill currently doesn’t include means-testing: regardless of income, all Oregonians would be able to access the same voucher amount.

One particularly notable data point is that nearly 30% of survey respondents indicated they were new bike riders. At a time when Portland’s bike ridership numbers are falling, we can look to Denver where electric bikes are bringing new people into the fold.

There’s a process to getting these programs right

The report gives a rundown on how Denver started its e-bike rebate program and why other cities are embracing these incentives, offering some advice for designing similar initiatives.

“Electric bicycles reduce barriers to bicycling by helping people ride more often and for longer distances…[e-bike incentives] create low-cost, accessible, and efficient solutions for achieving our nation’s climate, sustainability, health, and transportation goals,” Ashley Seaward and Not Banayan from PeopleForBikes write. “In the United States, the transportation sector accounts for nearly a third of total carbon emissions. Electric bicycle incentive programs target this specific segment of carbon emissions by making this emerging technology more available to Americans seeking affordable mobility solutions that reduce their emissions and better connect them with their communities.”

Denver’s e-bike rebate program is funded through the city’s Climate Protection Fund, which uses a $0.25 sales tax to pay for local climate mitigation projects including the vouchers. After nine months of the program, the city had spent $4.7 million on e-bike rebates.

The City of Denver has several tips for cities and states organizing their own e-bike incentive programs.

- Budget accordingly

- Keep the resident application process simple and easy

- If e-cargo bikes receive a different level of incentive, try to make the definition of e-cargo bike as objective as possible

- Make the incentive applicable at the time of purchase

- Build relationships and work with local bike shops

- Lead early and genuine outreach in lower income neighborhoods

- Make a plan for how to collect data from individuals once they have purchased the ebike

- Think holistically about inducing demand for biking in your region by prioritizing investment in safe infrastructure

E-bike rebates don’t remove the need for shared micromobility systems

The report states that in order for e-bike rebate programs to be as effective as possible for reducing car use in a city, they must work in tandem with bike and scooter share programs. Denver saw their highest ridership of shared electric bikes this past summer during the e-bike subsidy program, “indicating that the rebates are a complement to the shared program and vice versa.”

According to research from Ride Report, the average trip length on a subsidized e-bike is 3.3 miles, while the average trip distance on a shared e-bike is 1.6 miles.

“The data indicates that the owned ebikes purchased through the rebate program are for longer and more frequent trips, and during commuting type times compared to shared ebikes. This again is an indicator of the distinct and complementary nature of shared and owned ebikes, both of which are encouraged through public policies and programs from the City and County of Denver,” the report states.

The carbon emissions savings are real

How valuable are e-bikes as a tool for climate action? While anecdotal evidence is positive, this hasn’t been fully hashed out yet.

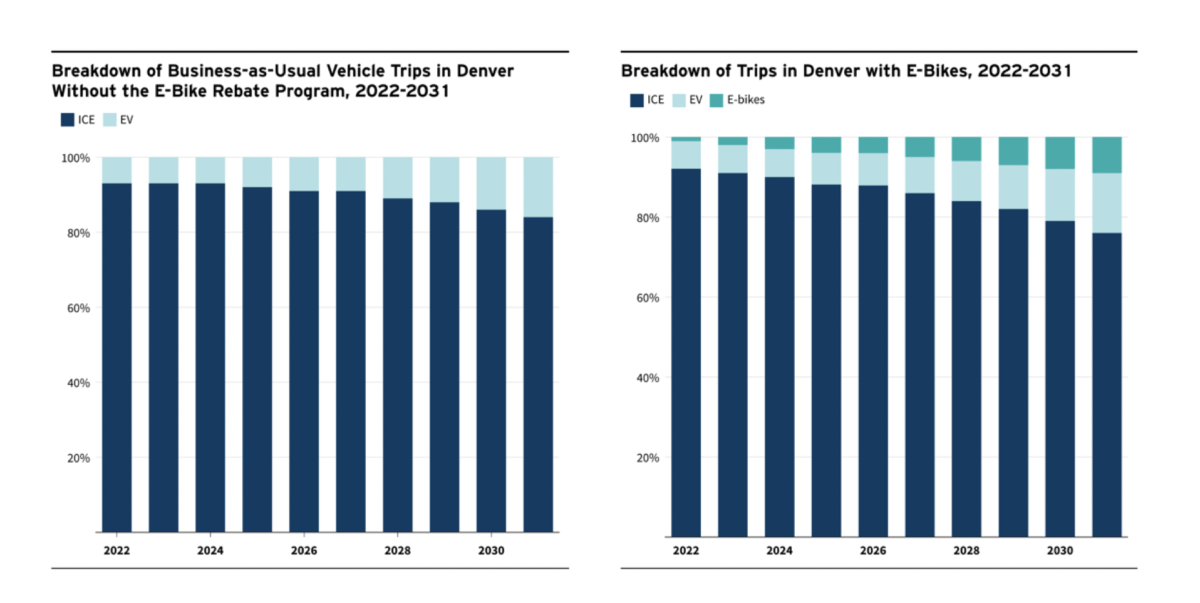

“While ebikes are very popular with users, their full economic and climate benefits are not fully understood. It can be difficult to assess the impact that shifting trips from ICE and electric vehicles to ebikes will have on transportation emissions, making it difficult for policymakers to incorporate them into climate policy,” the report states.

According to RMI’s research on how e-bike subsidies help combat climate change, this program saved 94 lb CO2e per dollar spent, for a total of 2,040 metric tons of CO2e avoided emissions per year. RMI’s research shows that e-bikes aren’t just superior to internal combustion engine (ICE) cars, but they’re also more effective for avoiding carbon emissions than electric cars, which currently receive the vast majority of government subsidies and rebates. If an ICE vehicle produces .54 metric tons (MT) of CO2 emissions, an electric vehicle produces .19 MT and an e-bike produces .01 MT — a huge difference.

RMI concludes that “establishing a program similar to Denver’s ebike rebate program would likely reduce GHG emissions from transportation in cities and save residents money” but ” until this point, the exact impact of the program on cities’ climate goals has been hard to determine.” RMI’s carbon savings calculator “can arm advocacy groups and cities with firm numbers to quantify impacts and help officials understand and assess the value of adopting a similar program.”

More benefits

Some other outcomes of the e-bike rebate program are more tangential, and can be difficult to quantify. One such advantage that the report didn’t touch on is how the rebates are creating a broader coalition of bike advocates, resulting in improved bike infrastructure even for people who didn’t receive a voucher.

A recent CityLab article looks at how residents getting their “first taste of the joys and anxieties of navigating their city on two wheels” after buying an e-bike through the rebate program may be compelled to “add their voice to those already clamoring for better bike accommodations.”

The Denver report contains more information about the e-bike rebate program and is a very helpful document for understanding the benefits of such initiatives. You can find the full report here, and stay tuned for more updates on Oregon’s e-bike bill.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Nice to see Denver spell out that micromobility and e-bikes are entirely different things. Maybe someone at ODOT will read this report!

Rather than spending taxpayer dollars on buying fancy toys it would be much more “transformative” to simply create a safe and clean city of Portland with MUP’s and street paths that families and women could use without fear. That would do the most to increase the bikeshare of Oregon.

That and traffic enforcement

This report is a joke.

I agree, but also not that different than some of the economic and demographic reports you cite.

Survey samples don’t, in fact, have to include like, half the population in question. 70 riders is not a bad sample size. Also, unless you can think of some systematic reason iOS users would behave totally different from Android users (I can’t), that’s a most likely irrelevant little detail.

It’s not “bad” — it’s ridiculously underpowered and relies on notoriously inaccurate “self-reporting”.

WTF?

First of all, low-income people are far more likely to not own a smart phone and, secondly, low-income people are far more likely to own a cheap android phone.

70 is not an underpowered sample of a population of only a few thousand. It’s not the entire population of Denver they’re sampling, only the people who used the program.

Furthermore,

I.e. this is accounted for. If there is any bias in this, it is only going to look better if they sampled more users.

I guess testing the null hypothesis is just not cool anymore…

I would love to hear more about how Denver is doing this:

I have been noticing that e-vehicles have added increased hazards. E-cargo bikes are bigger and faster than bikes. One-wheelers seem much faster than e-bikes and the riders usually have full leathers and motorcycle helmets on- not great in a 5-foot bike lane or in the park. E-skateboards and e-scooters tend to do A LOT of weaving round for some reason. Also, there are now lots of motorized bikes, scooters and skateboards, etc on all of our bike lanes and our paths. Are motorized vehicles allowed on paths? In parks? I have seen a few motorized bikes and a motorized skateboard powered by an ICE- is that acceptable? PBOT does not appear to be thinking holistically about this, they do not seem to have acknowledged that vehicles using our bike infrastructure are getting bigger, faster and more powerful. So how did Denver prioritize investment in safe infrastructure?

Maybe they don’t actually rely on city-provided infrastructure and just ride on whatever streets they want to in Denver? It’s not that hard to do in Portland either; waiting for PBOT to finally ‘get it right’ is a fool’s choice.

If any car trip is displaced by a trip on a vehicle weighing less than 100 pounds, I’ll count that as a win. There are people with poor ideas about how to ride around other bikes but I expect they will learn. I don’t relish close passing within bike lanes but I also know that even at 28 mph the closing speed of an e-bike is less than that of most cars and the rider is little more protected than I am. One-wheels sketch me out, how are they fail-safe? –but they are sorta cool.

No big surprise, Denver has twice the number of sunny days per year per year as Portland.

What does that have to do with anything? Our weather is perfectly fine for riding a bicycle year round. People are just going to use the mode that gets them to where they want to go the fastest, and a little sprinkle here and there isn’t going to stop them. Case in point, Netherlands.

We do have an infrastructure and urban design problem, in that the fastest way is by car almost 100% of the time. It’ll take a long time time to change that, and if ebikes add any momentum we should take that.

“We do have an infrastructure and urban design problem, in that the fastest way is by car almost 100% of the time. “

This is absolutely 100% false! It is incredible to me that this would appear in this blog. You must not ride a bicycle around town at all. I can ride anywhere within 5 miles of my house on a bicycle in this town faster than a car. Easily. I do it everyday.

This constant whining here about infrastructure is nothing but excuse making silliness for people that don’t apparently even attempt to ride around town.

Rain does in fact deter people from bike riding. Maybe it doesn’t in Holland, but it does here.

I call BS, a whole lot of people in Portland do care about riding in poor weather, and they don’t do it. It takes a certain commitment to gear up and ride in the rain 9 months out of the year, which you obviously have, but a great majority of Portland residents do not share.

Denver is an exceptionally sunny place, but Portland is sunnier than London, Amsterdam and Copenhagen. People don’t just ride bikes because it’s nice out.

This is good news, and good to see real data that should (read: likely won’t) tamp down on a lot of the nay-sayers’ rhetoric about how people are just buying toys they won’t use, etc. It sounds like the program in Denver really is working well. And it seems like ours is similar enough it should be able to work too.

While of course there are plenty of other things we need to do, if we stopped moving forward on any actions because there are other actions we could also do that some people think are more important, literally nothing would ever happen. This is not an exaggeration. The fact that this is relatively easy to do and has a measurable benefit is great. Lets get this passed, and then hopefully as suggested in the article, this will add to the people who care about improving bicycle infrastructure.

Also this:

All I can say is good. This is good. Means testing is always a way to keep from actually spending the money that is allegedly allocated to some purpose. There is no reason to means test it.

The Denver program was means tested.

If there is a tiny amount of money available to address a critical social issue (due to capitalism), the only moral choice is to make sure the people who don’t need it get their fair share. Do you also support flat taxes instead of means-testing taxation?

Yes, and means testing usually sucks. The reason it sucks is that usually it is difficult to access. How are people supposed to prove to the bike shop they’re getting the discount from that they make a certain amount of money? Should they bring pay stubs? Last year’s tax returns? These are all weird and not really something your local bike shop should have to deal with (or is prepared to deal with). We are constantly in this false mindset of scarcity. We should do it without means testing and then after a year or two if the funds all get used up instantly we can consider expending it or possibly adding means testing. But I don’t think it’s likely needed.

Taxes are easy because the means testing is literally done by the same organization that knows your means with all the information they would need to know to do the means testing. It’s not comparable.

You apparently have no idea how this stuff works… The state is paying the subsidy, they have tax records at their disposal for this very thing… How Do you think programs like SNAP work? The Honor system?

I don’t like any subsidy for e-bikes over regular bicycles but it should be means tested at the least.. Simple to do and it won’t be hard to access.

Your condescending view towards lower income people is not flattering, people have enough brains to access these kinds of programs if they are out there.

The rebate is available at time of purchase. The state isn’t involved at that point, only your local bike shop.

Calling me condescending to lower income people is literally the opposite of the truth. I want lower income people to use this program, and for that it has to be easy to access. Not nearly as many people access the benefits they are entitled to as they could, because it’s confusing and difficult to access them.

There are 700,000 SNAP recipients in Oregon….

Low income people can access programs just fine, thank you.

if what you say is true and anyone can walk into a bike shop and get $1200 off an e-bike at point of sale, this is clearly an assinine program that should never be implemented…

You still don’t get it. SNAP recipients have a whole complex system set up that allows them to spend money anywhere but only on certain things. A better running government might be able to quickly whip together a parallel system that gives you benefits at time of purchase but only for certain other things, but that seems like too much to ask this bill to do. What I expect would happen if they wanted to make this means tested is it would end up being a tax rebate that you have to wait until tax season and itemize your taxes and whatever on an already baffling tax system that we have, and people just wouldn’t do it. Yes, someone can go sign up for SNAP because 1. they need to eat and are extremely motivated to do so, and 2. it’s an old system that has a lot of infrastructure in place to make it usable.

It depends on the structure of the test and subsidy. If it’s a point-of-sale thing (which is what I recall the Oregon bill would be) it would be a pretty big leap to apply any sort of test in the store itself. If it’s a rebate, I would think it would be pretty easy to income-grade the subsidy.

And SNAP is not exactly simple. If you are a single person, you are ineligible for SNAP if you’ve been unemployed for over 3 months. If you have over $2500 in assets you are ineligible (regardless of income). The application process is not straightforward either. It requires an entire bureaucratic apparatus to administer (which isn’t cheap) – which is usually a primary argument against means testing.

Realistically, an e-bike rebate sounds pretty trivial to means test – but does the state of Oregon have the administrative capacity to handle it? Is it worth spending a non-trivial amount of money to spin one up, just to administer like <$5 million in money? I can’t speak for everyone, but my issues with means-testing are rooted more in real-world considerations than philosophy. It would be nice to scale things by income, but that’s not always feasible.

If oversite of $5 million dollars is so trivial and anyone can raise their hand and get $1200 off a bicycle, this is just a ridiculously thought out program.

If that’s the case what prevents a bike shop from raising the price of E-bikes $1200 and pocketing the entire amount Plus the rebate?

If you can’t oversee who is getting the rebate you can’t oversee the bike shop…the whole program is just silly.

I’m really in favor of anything that gives $1200 to anyone who wants it and the fact that it’s focused on a tool to give people an option to drive less is great. So it doesn’t seem that silly to me. If they give it to everyone no questions asked, it benefits average people the most. Since most people aren’t super rich or even upper middle class, most people getting this will derive a pretty big benefit. Even if they were going to buy an e-bike anyway without the rebate, that gives them $1200 more to spend on other things.

42% of households in Portland earn more than $100,000 per year (2021 ACS). Median household income in Portland is $78,500

I talked to my math guy, and it turns out 42% is not most people. Also I think it’s implied that cost of living is an important factor, and it’s high in Portland.

You are getting so silly it’s hard to even respond….

Yes, we live in a capitalist society but this does not mean that redistribution away from rich capitalists to poor working class people is necessarily “austerity” or, even, bad.

This is how means testing works in non-corporate-fascist nations. The barriers built into this sh*t-hole nation’s social safety net are intentional cruelty, not inherent flaws in the “concept” of a social safety net.

Of course, I just don’t believe that adding means testing will have the desired effect. Too often, means testing makes it so the benefits just aren’t used, which ironically has the effect of actually being austerity. If anyone could propose a way to do it that would truly be low friction and not throw up unnecessary barriers, that could be great. I just don’t see how.

I don’t even know what to do with the rest of your comment. I agree our social safety nets are intentional cruelty. But you are the one that suggested this is like progressive taxes, which are only easy to implement because it’s done by the organization that collects your taxes. It’s easy for the IRS to tax different amounts because they’re the ones calculating the tax. So I don’t know what you’re getting at with the the rest of your comment, it seems to be polar opposite of the point you were making before.

The organization that collects taxes is part of our government (state or federal) so social benefits can have as little barrier as filing your taxes. In fact, from an economic perspective there is little difference between negative taxation and a social welfare benefit. In the context of capitalism, I am a fierce political opponent of anyone who supports a universal basic income/flat-tax but I am a friend of anyone who supports a guaranteed-basic-income that allows for a decent livelihood (e.g. means-tested/progressive negative tax brackets).

However, the idea that access to social welfare benefits would only be available if once can demonstrate need based on backwards looking tax/income data would be laughed at in nations with comprehensive social welfare systems. In Europe benefits tend to be either automatic/obligatory (e.g. means-tested) or supplementary/need-tested.

Since one explicit goal is to have this benefit at the point of sale, they cannot do this. Your taxes are done once a year, and the people for which a few hundred dollars makes a meaningful impact on their ability to buy a bike are not going to be able to wait until tax time to get that money back. If you care about making it easy for them to use it, you can’t make them wait until tax time.

I guess one way to do it could be some special voucher people can get and take to the bike shop (like food stamp cards). That should be pretty straight forward. I don’t know if Oregon is in the place to do it on our own, but if that little quibble is going to be the difference between getting a program and not, I’d take the one that is not means tested over one that is means tested and has a complex new system for distributing the benefit. Sure it should be easy, but I don’t see that happening.

It’s a government rebate program so approval could be as easy as documenting that someone receives SNAP, TANF, and/or medicaid (just as easy as as looking up the prior years income on tax rols).

Cool, if that’s easy enough for the people at your bike shop to do that when you’re getting a bike, you should let someone know other than me since I didn’t write the bill. I’m automatically suspicious of means testing unless it’s clear that it’s not just a point of contention thrown in to derail an otherwise perfectly good bill.

I’m for these programs, but I’d be curious to know how many of the ~5,560 who got the rebate were in the income-qualified group that got the higher rebate. I also feel like an average of 26 miles/week is kinda low? My commute is 7 miles, and I do at least 100 miles a week at least on my ebike.