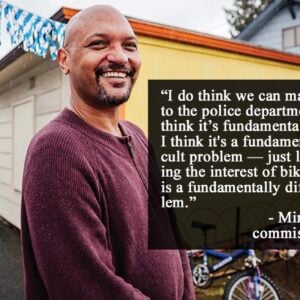

Keith Liden is a southwest Portland-based active transportation advocate and land use planner who has been a regular participant in local transportation circles ever since he caught the bug on the advisory committee for the city’s first Bicycle Master Plan, adopted in 1996.

More recently, he has served on several advisory committees: the Portland Bicycle Plan for 2030 (including lead author of the Bicycle Facilities Strategy to Reach Platinum Status in SW Portland), Central City 2035 West Quadrant Plan, Portland Transportation System Plan, and the Southwest in Motion (SWIM) plan.

And a few years ago, he completed a 25-year stint on the Portland Bureau of Transportation’s (PBOT) Bicycle Advisory Committee (BAC). Liden would have gladly continued to serve but was term-limited out.

BikePortland caught up with Liden at last weekend’s southwest BAC tour, and invited him to reflect on his years of advocacy and the next steps forward to making Portland a better biking city.

BikePortland: The world is such a different place than it was in the mid-nineties. Can you comment on the arc of transportation changes you have seen over the past 28 years?

Portland said “no” to the Mt. Hood Freeway and built the first light rail line instead. For a planner and active transportation advocate, it was euphoric, and the sky was the limit.

Liden: Well, it’s been longer than 28 years. I first lived in Portland in 1974. I just loved this place after being raised in the Chicago suburbs. Perfect size, lots of positive energy, Goldschmidt as mayor, etc. Portland said “no” to the Mt. Hood Freeway and built the first light rail line instead. For a planner and active transportation advocate, it was euphoric, and the sky was the limit.

We seemed to reach our peak during the Bud Clark/Vera Katz days (with Earl Blumenauer on City Council), although momentum for bike improvements continued under Sam Adams. Since then, Portland appears to have lost its mojo. Could you imagine us making the equivalent decision of squashing the Mt. Hood freeway in favor of MAX today?

SW Corridor is a telling example of where we are now. Southwest Portland needs significant active transportation investment to support light rail. Instead, the plan emphasized park and ride along with active transportation eyewash, like calling sharrows on a collector street a full-flown bike facility, to make the project look worthy of a funding match from the Federal Transit Administration.

In comparison to our inspired transit projects from the past, SW Corridor was a real letdown. There was definitely more concern about auto throughput than pedestrians, cyclists, and transit patrons. It’s too bad because with serious planning and investment, I believe it could have been a game changer for southwest. Obviously, the project didn’t receive voter approval, and it’ll be years before it resurfaces – if at all.

We obsess over making driving wonderful any time of day, allocate our transportation funding accordingly, and wonder why more folks aren’t riding bikes and walking on substandard or non-existent facilities. Give me a break!

BikePortland: What are some pressing next steps bike advocates should push for today?

Liden: We need to push for active transportation funding that is commensurate with our planning aspiration to have a 25% bicycling mode split by 2035. However, as a region, we don’t put our money where our mouth is. Bicycle and pedestrian funding is a tiny fraction compared to what is provided to enhance auto capacity and transit. We obsess over making driving wonderful any time of day, allocate our transportation funding accordingly, and wonder why more folks aren’t riding bikes and walking on substandard or non-existent facilities. Give me a break!

BikePortland: And completing bike networks?

Liden: This is a significant problem in southwest. PBOT certainly makes improvements to the bike network here, but too often they are isolated and disconnected, and networks are only as good as their weakest links. To get the most from its investment, PBOT must focus more on connectivity.

BikePortland: You’ve done a lot of committee work, and I know accountability is an issue for you. Do you have any thoughts to share about that?

Liden: Boy, we could spend a long time on this one! Large bureaucracies like the city can be difficult to manage under the best of circumstances.

Off the top, I think we have two major types of accountability problems. First, there are the silos. Each city bureau is a silo, and in the case of PBOT, so are the departments. In too many cases they don’t communicate or work together as they should. In particular, if a plan wasn’t created within your silo, your bureau or department often doesn’t feel obligated to care or help implement it even though it’s a citywide plan.

Second, once a plan is adopted, the staff typically goes off to implement as they see fit with minimal public interaction other than to announce the next improvement project. SWIM, as an example, is a supposedly short-range plan that will nevertheless take many years to implement due to insufficient funding. Southwest residents should have an opportunity to participate with staff in project prioritization. After all, we are the customer.

BikePortland: Do you have any final thoughts?

Liden: We need to understand why the bicycling mode split has declined. Beginning with the 1996 Bicycle Master Plan, the city adopted the “build it and they will come” philosophy—and it worked. The bicycling mode split steadily climbed.

However, around 2013-2015, the bicycling mode share began to decline. Covid and new work/commuting patterns complicate our understanding of what’s going on, but we need to discern why more people aren’t riding. Our system is certainly better than it was in 2015, so why don’t we see an upward trend? I believe Metro, Portland, and other governments in the region should sponsor a comprehensive survey to understand what is keeping people from riding. The survey should focus not on those who are riding now, but the “interested but concerned” category who are not riding but would be given the right conditions. This knowledge could be used to improve our investment strategy. It could make future efforts more focused and effective.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

“PBOT certainly makes improvements to the bike network here, but too often they are isolated and disconnected, and networks are only as good as their weakest links. To get the most from its investment, PBOT must focus more on connectivity.”

IMO, this sums it up. PBOT is focused on isolated segments of bike improvements, many which are only done to get bikes out of the way of cars! Years of improvemnts for cars while not actually creating a connected network is why we are not seeing more bike ridership. People cannot use the bike infrastructure we have to safely get around, and there are increasing numbers of cars driving more dangerously.

IMO, it’s those damn cell phones/smart phones. Participation in exercise of all sorts have declined, including walking, golf, and team sports, while health issues from a lack of exercise has steadily increased even before covid hit.

For many years East Portland had no representation or only token representation on the BAC (people who lived in East Portland but said nothing at BAC meetings nor communicated with anyone in East Portland). For those many years Kieth was also an excellent advocate for both SW and East Portland.

Interesting that Keith sees the SW Corridor project as flawed for both transit users and cyclists. The bottom line is that PBOT and ODOT are too afraid of the blowback they will get from drivers if they do anything to slow them down. So the projects for transit and cycling are therefore crappy.

We need leaders who have the courage to do the difficult, right thing.

The rose lane through Hillsdale is making a lot of people unhappy because it is taking away and Hardesty is pushing forward despite the backlash. It’s an improvement, but also does not far enough.

Thank God for term limits. Liden provides continuity, historical perspective, and a deep understanding of what works and doesn’t work for bicycling in Portland. That’s the kind of BS that can derail a committee following the “social justice” vision of people like Sarah Innarone.

Well, if there was a self-serving greedy politician today like Goldschmidt was back then the answer could be a yes.

When Goldschmidt and his Construction Company friends realized there were larger profit margins for train construction vs. freeway construction is it any surprise what Goldschmidt supported?

Unfortunately, this is true. Everything from transit planning to construction to purchasing vehicles has a much higher profit margin than anything related to stroads and highways. Public transit is perceived as a public good that is progressive and a social positive, so the public has a much greater tolerance for transit-related cost overruns, graft, kickbacks, delays, and mission creep, almost as much as for sewers, fire-fighting equipment, police, and the military. The higher the perceived value it is to society, the greater the tolerance for corruption.

Clearly our society has a very low value on bike and pedestrian infrastructure – the corruption index is relatively low.