Oregon is facing urgent environmental problems which are attracting the national media. Last month, The Atlantic published a gripping piece about the heroic response of Molalla residents in fighting the converging Beachie Creek and Riverside fires last fall. This week, The New Yorker ran an article on our “heat dome” event earlier this summer.

This looming climate catastrophe is the difficult backdrop against which Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) project managers present their plans. Last week, the Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee (BAC) meeting heard an update on PBOT’s Streets 2035 plan from project manager Matt Berkow.

As we’ve reported, the purpose of Streets 2035 is to deliver a framework for resolving competing demands on rights-of-way, with the end goal of identifying

a right-of-way allocation framework that moves streets forward to achieve citywide objectives, minimizes the need for an exception process, and helps bureau staff achieve a predictable and transparent process for themselves and external stakeholders.

Streets 2035 is currently in its middle phase, cross-bureau technical conversations seeking to identify “opportunities for flexibility,” and hopes to finish up in 2022. Berkow has a tough job ahead of him. Engineers rely on tables and standards which are often used to justify a “no” rather than to create a path to “yes.”

Advertisement

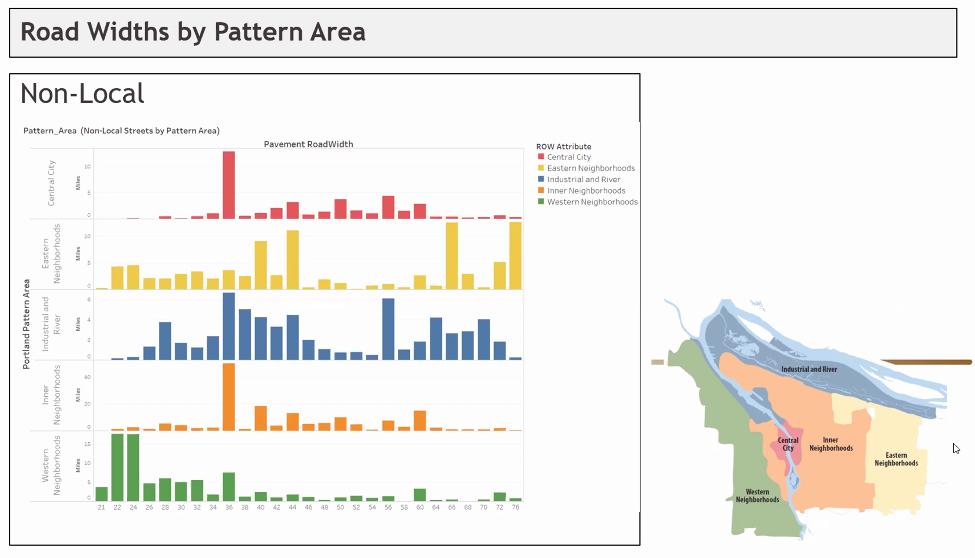

One of Berkow’s most informative slides was “Road Widths by Pattern Area” (below) which clearly shows that East Portland has the lion’s share of our city’s 76 foot wide roadways.

But BAC member (and The Street Trust executive director) Sarah Iannarone was not an easy sell. She brought up tree canopy, communication between bureaus, and amenities across wide spaces and ended by exclaiming, “Where is the innovation coming from?” Indeed, East Portland’s wide streets and lack of tree canopy are deadly problems which urgently require solutions.

Maybe Iannarone brought up innovation because she had heard the same lecture at PSU’s Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) that I had listened to a couple of weeks earlier. Urban Planner Adam Millard-Ball gave a talk titled “Turning Streets Into Housing.” Although Millard-Ball’s talk focused on housing prices and residential streets, it is not much of a stretch to apply his arguments to mixed used and commercial areas, and to substitute housing for parklets, tree-filled promenades and taco-trucks.

In the spirit of innovation, let’s look at some of his ideas.

Millard-Ball is hot off an article titled The Width and Value of Residential Streets published in the Journal of the American Planning Association. The article is an economic analysis of the value of streets and their opportunity cost which, he argues, informs the question of how wide a street should be. He calculates the combined value of the residential streets in 20 US counties as nearly $1 trillion. And he makes the case that this wasted value ends up constraining housing supply and inflating the price of housing, especially in already expensive coastal areas.

In what reads almost like a response to Streets 2035, he writes:

The planning and design discourse, however, has largely focused on how to divide up a given quantity of land between competing uses; that is, how to allocate a fixed street right-of-way. Less attention, either normatively or empirically, has been paid to how much urban land is or should be devoted to streets. The tradeoff between land for streets and land for other urban uses—parks, housing, commerce, public facilities, and so on—is implicit or ignored altogether.

His TREC talk was simpler than the paper, and more provocative. Using a 60-foot wide suburban street in San Jose as an example, Millard-Ball calculates that the ROW in front of each house is worth almost $250,000. He makes a strong argument that a residential street doesn’t need to be more than 16 ft wide, and suggests reclaiming much of the ROW for additional, front-yard Accessory Dwelling Units. (below)

This might seem outrageous at first, and I found myself wondering how it would go over at a Portland neighborhood association meeting, but some cities are already part way there. The New York Times ran an excellent story last week about the Clairemont neighborhood in San Diego which is experiencing an ADU boom. The San Diego real estate market is terribly expensive, leaving many people who grew up in San Diego unable to buy a house as adults. The Clairemont Mesa area was developed as modest, middle-class subdivisions in the 1950s. It also happens to be centrally located. The article described the competition between residents building backyard ADUs and adding 2nd floors intended for their parents and adult children, and developers looking for a piece of that ADU action, for a profit. It sounded frenzied, and you could imagine some people snapping up any ROW real estate in front of their house they could.

The New Yorker article, titled “Under the Dome” by James Ross Gardner, featured PSU professor Vivek Shandas, who studies urban heat islands. When the heat dome hit, Shandas grabbed an infrared heat camera and a temperature sensor and drove to Lents where he measured an ambient temperature of 124 degrees. His camera registered the surface of the asphalt at 180 degrees. He then drove to the forested Willamette Heights neighborhood in NW Portland, where the temperature was 99 degrees, 25 degrees less.

96 people in Oregon died in the heat wave. Lack of tree canopy and an abundance of asphalt kills. Maybe we can get rid of some of that East Portland asphalt and plant trees.

Innovation and big-thinking are crucial. So is the meat and potatoes of effective local government. It is important that Streets 2035 succeeds. We need all the bureaus, and the groups within bureaus, to be working together toward the big goals of our city.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Motor vehicles are to roads, what goldfish are to goldfish bowls. They grow larger if you give them more space. In Europe, where the roads were designed well before automobiles, the cars are necessarily smaller. In the US, we have indulgently wide roads.

Most of Europe has “indulgently wide roads” too, most built after 1850 or so. It’s only the inner core of cities where streets are narrow, and only those with a medieval past or earlier. It’s worth keeping in mind that European buses and semis are the same width as in the USA, as are most of the freeways and tollways there, as well as the railroad gauge. But it is true the cars there are by and large narrower than here. Paris is famous for ramming wide boulevards through its medieval core long before the automobile, then many other European cities followed suit. Many cities built wide boulevards where the city walls used to be. Most Dutch cities outside of Amsterdam have large networks of very wide streets.

There are many US cities with narrow streets in the inner core: Philadelphia, Charleston SC, Boston, Georgetown in DC, and so on.

Well, that’s anecdotal evidence for you. I lived in Norwich UK for a few years. They do have a bus line (can’t recall the name ATM) that is much smaller, closer to a large van. I used to ride a Tri-Met to work with a Tri-Met engineer. He told me that would never work here because of the bottom line issues; they’d need twice as many drivers.

I’d say the lorries are smaller as well. There are big rigs, but a lot more smaller trucks.

On average I’d say Europe tends to have smaller vehicles.

On average, that is correct. But averages are not always truly descriptive.

On average, fuel costs in Europe are much higher and vehicles are more heavily taxed so it’s not so simple as “roads are smaller because they were there before cars”.

My experience has been that European roads are very well maintained and a lot of money goes into them. The main highways are no different than ours with regards to size, speed and capacity (tolls are higher, though). Saw plenty of mid-size cars on the highways. FWIW, I have only driven in Spain, Switzerland, France, Monaco and Italy.

Trucks, now that is a different thing entirely. American road identity incorporates big trucks and the ability to go anywhere off road. Not a lot of big SUVs or pickups in Europe but I think as mileage gets better, that is changing.

Europe has lots of huge semi-trailers (called “lorries” in the UK) which are built to the same standards as in the USA – the containers are interchangeable on the ships, and many of the trucks in the USA are made by European companies. Only Australia has bigger semis. But I agree with Jason, there are a lot more of the smaller and narrower type trucks in Europe, that they are more common, but they are also increasingly being used in the USA too.

Europe has lots of newer roads that are built to similar widths as in the USA, but this is far from universal; but then again there are many narrow non-standard highways in the USA as well, particularly on the East Coast and in Appalachia. Europe has many medieval roads that have never had their rights-of-way expanded (particularly in the UK and Italy, and in the inner core of many cities), and the ancient Roman road network is still widely used in England, France, Belgium, western Germany, and Italy.

The small car size in Europe is more likely caused by the high gas prices rather than by narrow roads – when gas prices went through the roof in the USA, more Americans bought small cars.

And then again there are the extremes – the Humvee is an extra-wide US vehicle designed more for combat than to deliver kids to the soccer game – and the 3-wheel Piaggio utility vehicles in Italy (including dump trucks, cement mixers, and tiny fire trucks) that are designed to go up and down 6-foot wide alleys and stairs of medieval city centers.

Even new roads in Europe tend to be smaller than new American roads

“In the United States, the Interstate Highway standards for the Interstate Highway System use a 12 ft (3.7 m) standard lane width, while narrower lanes are used on lower classification roads. In Europe, laws and road widths vary by country; the minimum widths of lanes are generally between 2.5 to 3.25 m (98 to 128 in).[11] The federal Bundesstraße interurban network in Germany defines a minimum of 3.5 m (140 in) for each lane for the smallest two lane roads, with an additional 0.25 m (9.8 in) on the outer sides and shoulders being at least 1.5 m (59 in) on each side. A modern Autobahn divided highway with two lanes per direction has lanes 3.75 m (148 in) wide with an additional clearance of 0.50 m (20 in) on each side; with three lanes per direction this becomes 3.75 m (148 in) for the rightmost lane and 3.5 m (140 in) for the other lanes. Urban access roads and roads in low-density areas may have lanes as narrow as 2.50 m (98 in) in width per lane, occasionally with shoulders roughly 1 m (39 in) wide.[12]”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lane

Rural roads in Europe tend to be one-lane, often 3m from stone wall to stone wall, or rock wall to cliff in mountain areas. Even two lane roads incorporate flower boxes that narrow the road to one lane. The result does not appear to be constant head on collisions, but drivers who know they must share the road or nobody is going anywhere. I miss cycle touring in Europe – maybe next year.

And to add to that, we then design roads to fit the larger vehicles. Lots of American engineers design geometries even in the middle of urban centers to accomodate a WB-67 (the longest single trailer semi truck) which is just insane.

And now I’m seeing more frequently designing for an F-450 so that fits within the lanes during turns.

Its a terrible feedback system that has made North American vehicles stupid huge and unsafe for anyone else not in them.

Part of it has to do with fuel costs.

Would love to see if Streets 2035 (or another city program?) has a usable map of where underground utilities are (and aren’t) so Portland can have a simplified process to plant trees in the ROW where there is no planting strip or no sidewalk. These on Hawthorne include curb but there is no reason to require that: https://goo.gl/maps/8v746dxKbLSGerhv9

NARROW STREETS?! BUt hOw Do I pARk mAh PIckuP?!

On ur lawn, of course.

Call me crazy, but in addition what if we required roof tops over a certain square footage, parking lots, and places like the Union Pacific – Brooklyn Yard to be covered by parks and gardens? It would be a massive undertaking for many areas, but looking at googles satellite images there are more than just roadways that were once green.

You’re crazy 😀 and I love the idea of rooftop flora. There is some around town, more is better in this case.

Aside from the UP yard being private property, how would the diesel exhaust from all the trains and trucks be dealt with? Tunnels have to have massive air movement systems, and the exhaust points concentrate all of the pollution in one area.

Part of the massive undertaking, and a large flat area would create different fluid dynamic challenges than a tunnel does but funneled exhaust does open the door to capturing and filtering it.

How about getting rid of slip lanes to make for land for a pocket park, business, or ADU housing? Beaverton is removing the north-bound slip lane on Western Avenue by SW Allen Boulevard but refuses to make the edge of it into a path away from motordom fumes, but the new land will be landscaped.

“Maybe we can get rid of some of that East Portland asphalt and plant trees.”

I’m all for it, and when I was involved in transportation advocacy in East Portland for the EPIM, it was suggested by many folks. The greatest resistance wasn’t from the neighborhoods there nor the businesses, it was from PBOT and an unwillingness by city hall to pay for a complete rebuild for any East Portland stroad. PBOT also resisted at that time (2010-15) because they were convinced that streets were only for allowing car drivers to go as fast as possible as quickly as possible, and that the Fire bureau would veto any obstructions (we later learned that the Fire Bureau hadn’t talked with PBOT in decades about the issue and they were all for the changes.)

It is a VERY expensive proposition to do any sort of rebuild, particularly one of adding tree wells in the parking or sewage zone of a street – these suggestions will take far more money than the city can currently generate. Except on Division and Powell, adding trees in the median is possible on nearly any stroad, aside from the astounding cost of ripping out everything in the center and the local inconvenience of water shut off for a period.

But of course the wealth is there. What we lack is a society that really prioritizes the building of common wealth and public space- and it’s compounded multiple benefits- over the private accumulation of wealth that degrades and despoils public space. In the Netherlands where accumulation of public wealth is prioritized more, cities are narrowing streets and installing “expensive” tree wells and bike paths as a longterm investment in public wealth and health. Here is just one example in Hatertseweg street in Nijmegen, Netherlands where I lived in 2009.

I just wish within all these plans, the city actually enacts some kind of enforcing language. I am sick of ‘But what about PARKING, PARKINGG, PARKINGGGG’ everytime these plans get used. I hope the POEM strategy helps, but once again: lots of plans…

I would love to see the city shut down a lot of intersections and/or add parks mid-blocks such that through streets become dead ends. Maybe the wider, East Portland streets are even better suited for this as they have enough width for a proper cul-de-sac.

I lived by the Holman Pocket Park right after it was completed. Such a cool little park that greatly reduced cut-through traffic, Added green space, and it made a great hub for the neighborhood. There are SO MANY spots in portland with offset intersections that could work similarly. Traffic just gets diverted away, and the cut-through link is severed.

I look At the bucolic watercolor in washed greens and gentle pastels then I think of the RVs parked along SE Foster in various states of disrepair and surrounded by stripped cars & heaps of garbage. Fantasy vs reality. The “plan” will not sell in Sellwood

I’m always a bit amused when planning professionals, who really should know better, clearly don’t understand basic property law. Since Adam Millard-Ball is from the UK it might be a bit more understandable, but he is a professor at UCLA and really should get up to speed on U.S.—and specifically west coast—property law.

In the video discussion of expanding residential lots into the public right-of-way that takes place from 39:47 to 42:42, and again 48:00 to 49:08, Millard-Ball talks about the land in the ROW stating that the “city retains the ownership of the lot” and can lease or sell it, and that it “is a city asset”. This just isn’t true in most cases in the western United States. ROWs are almost always easements for public travel and utilities that were created as part of the street dedication process, but the underlying ownership is retained by the abutting properties. Cities rarely have property right to land in the ROW.

Here is a good explanation:

What is the Nature of a Public Right-of-Way?

As a second reference, search your local municipal code for “Street Vacation”. These code sections describe the process for extinguishing a public right-of-way easement, or vacating it, and returning full private use and control to the owner(s).

Don’t look to property tax assessor maps for this question. They do not show fee ownership boundaries—they show the taxable lot lines ending at the ROW line. Since the land under ROW easement has no private value, it is not included on assessor maps or taxed.

The link is to an organisation that provides resources to city governments in Washington state, and the court cases cited are all in Washington state courts. Do you know that similar precedents have been established in Oregon?

Portland City Code 17.84.005: ” A street vacation is the termination of the public interest in a right-of-way; it extinguishes the easement for public travel that is represented by the right-of-way. In the typical case, city and county governments hold an easement for public travel on lands designated or used as roads, streets, and alleys; they do not generally own the fee title to the property underlying the right-of-way.”

That being said, while I agree a planning professional should understand better, the underlying concept seems achievable working within the actual property law constraints, as long as there is a motivation for the property owner to make a deal. E.g., the City could condition vacating the ROW on the property owner using the property in the manner sought.

That’s right, Gary B. And I would add that fundamental changes to the ROW require agreement by both govt and fee holder. The fee holder can’t force a street vacation to take back land, it must be agreed to by the govt since ROW interest is dominant. Conversely, govt can’t convert the ROW to something other than a street without consent of fee holder(s).

This is common with street to pedestrian plaza conversions. The typical process is the street ROW is vacated on the condition that the fee holder re-dedicates all or part as a new recreation easement in its place.

There is a good example of this process in San Diego’s Little Italy neighborhood, in the creation of a one block plaza on Date Street. The existing ROW easement was vacated and partly replaced with a 56 foot wide recreation easement. That added a 2,400 square foot strip of private space to the parcels on each side, which they use for ground-floor restaurant dining areas.

In residential neighborhoods with lots of small lots, the ownership and consent requirements add a wrinkle to implementing what Adam Millard-Ball proposes, but with incentives it could work.

Thank you for your comments S.jones. Neighborhood associations in Portland receive notices about vacations of ROW, maybe by ordinance. In some areas we have a lot of paths connecting cul-d-sac streets to one another at the back end. Some owners don’t like ROW on their property, in other cases it just isn’t useful or being used. The NAs try to protect the ROW, although there have been some sad failures.

I agree that streets are too wide in most of the USA. If streets are narrower, drivers tend to slow down. I also think that the grid pattern exacerbates the traffic and speed issues, winding roads which have pedestrian/cycling cut throughs that inhibit motorized through traffic on residential streets would be great. As would more extensive use of roundabouts.

Urban planners should look at an area, consider its primary uses, and then consider how to design/redesign the streetscape to make the street safe for those uses. So for a residential street, 20 mph is probably a safe speed – well the streetscape needs to be adjusted so that motorized traffic naturally slows to 20 mph. Too often, in the USA, road planners are using the percentile test for setting speed limits – that puts the cart before the horse.

If residential streets are too narrow for F series Ford trucks and the equivalent from other automakers, there’s a pretty good chance people living in those residential streets won’t buy them – or they’ll move somewhere else.

Personally, I like it when the houses are built closer to the sidewalk and street, with a sitting porch in front. Then on a day off, or a warm summer evening, residents can sit on the porch and interact with their neighbors.

Great piece. The City had great intentions and considerable community support for expanding space in the public ROW to preserve and grow large form street trees as part of the Streets 2035 project. Many ideas were discussed during this November 2017 City Council work session: https://youtu.be/A_HogD9Asz0. However I am not sure there is enough of an organized constituency to keep the pressure on PBOT to prioritize trees in street redevelopment, which would have multiple benefits for active transportation and improved health and safety.

I don’t think Portland streets are “too wide”. If anything, as a driver they are uncomfortably narrow. The core of Portland is old, designed and built for a time before the car was even invented. A typical street PDX street has two lanes of traffic with parking on either side and it is TIGHT for a driver to navigate. I don’t know if ‘Twenty is Plenty’ is going to succeed here in PDX but for me as a driver, twenty is plenty!! We’re going into a time of year when visibility drops to nothing at twilight. If you drive, get in your car tonight in the 5:00 rush hour, in the rain, and tell me the streets are too wide.

As a cyclist, who has extensive experience cycling in San Francisco, Tucson and Bellingham, Wa., I can tell you that Portland drivers are just about the most careful, politest I’ve seen. Tucson, as an example, has very wide streets; the trouble is that it is full of drivers that pretend that cyclists and pedestrians don’t exist!

What is going to be the ultimate solutions?

Arteries dedicated to cycling. Educating cyclists to use them. Would you rather cycle west on NW Burnside from the 405 or Flanders, a newly dedicated bikeway? Is your answer ‘i’ll pedal up any damn street I please’ or ‘Flanders is too far out of my way’. Well, sorry. Those are the wrong answers!

Streets need to be in better shape. The poor quality of PDX pavement is a far bigger problem to me as a cyclist than cars. I know that may seem counter intuitive, but I have to keep a constant lookout for obstacles that would take me down. I’m 70. I can’t afford to fall over, even at a few mph.

20 mph needs to be the posted/enforced speed on all PDX streets.

Cyclists need to become more visible, clothing, lights. Are you a cyclist who is going to be out there tonight, October 20th, at twilight. Think about drivers who are in a hurry to get home, looking through a rainy windshield. Are you visible to them. I’m a warm weather, middle of the day cyclist at this point but if I were out there tonight I would have a couple of blinkers on the back, a good headlight and bright clothing on. Otherwise I would not be out there!

As someone who has biked in Portland for my entire life and regularly around town since 1985, I want to live in a city where not everyone has to be a cyclist with “extensive experience” to feel safe. I want to live in a city that is safe and fun for new cyclists as well as pedestrians.

Great!! I think I made a few suggestions in my original comment that would enable that . . . or?

Thanks for this wonderful article, Lisa. Unfortunately, I am not encouraged by the direction that PBOT is going currently with their Streets 2035 planning process. The lack of public process and transparency is troubling. The proposed update to the Pedestrian Design Guidelines (part of Streets 2035) really only consider the proximal pedestrian space and safety, and does not give enough consideration and space for street trees. It ignores the larger scale/longer-term safety hazards from extreme heat (heat domes and the like). There are so many opps we have RIGHT NOW under the Pedestrian Design Guidelines update to make more space for trees in right of ways. For folks who want to learn more, see my comments to PBOT on their Pedestrian Design Guidelines here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZT7rITq0iPWL2N_uOsUft_-EOgwH1VoI/view?usp=sharing

Thanks!

Ted

That’s a really good letter, Ted, thank you for sharing it, and for all of your work.