“What do the neighbors have to be afraid of? It’s buildings, people or cars.”

— Chris Smith, Planning Commissioner

An earlier version of this post was published by the Sightline Institute. It’s by BikePortland’s former news editor, Michael Andersen, who started covering the need for “missing middle” housing — especially in Portland’s most bikeable neighborhoods — for us in 2015. We last covered this issue in May, just before the crucial public hearings described here.

__

The most provocative housing policy event of this week in the Pacific Northwest started happening four months ago.

That’s because, in May, Portlanders did something almost unheard of in the world of housing policy. They showed up to say that in order to better-integrate neighborhoods and prevent future housing shortages, the city should allow more housing.

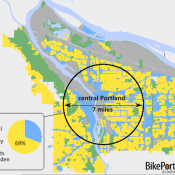

The place: Two public hearings of the Portland Planning and Sustainability Commission to discuss the residential infill project, a proposal to re-legalize duplexes and triplexes in much of Oregon’s largest city, reversing a 1959 ban.

The hearings were packed with people on both sides of the issue. But in the end (and here’s what was truly unusual) the people calling for the city to re-legalize more homes in more varieties slightly outnumbered the ones who showed up to defend the status quo—55 percent to 45 percent.

And last week, after months of deliberation, Portland’s planning commission gave other cities of the Northwest and beyond a peek at what can happen when housing advocates outnumber housing opponents: It recommended more housing.

This debate is the same one happening right now in small areas of Seattle and citywide in Vancouver, B.C. And in Portland, Team Housing just notched a clear win—cuing up the concept for a possible victory at the city council in the spring.

In that sense, the Portlanders who showed up for housing in May are part of something much bigger than an advisory vote in their city about re-legalizing triplexes. They’re part of a much larger movement, led in large part by Cascadia, to revive a more traditional pattern of housing than the one cities began experimenting with after World War II.

The vision is simple: gradually creating neighborhoods where more expensive detached homes and more affordable small plexes are all mixed together.

‘The biggest carbon impact of new construction is how big it is’

To prevent “looming” buildings, heights would be capped at 30 feet above the lowest point on a property, down from the highest point on the property under today’s rules.

“Seventy, 80 percent of the carbon impact of a house is heating and cooling the space.”

— Eli Spevak, Planning Commissioner

As housing advocates (including the city’s own housing bureau) suggested, the planning commission also said duplexes and triplexes should be legal (and subject to the new size caps) almost anywhere in the city.

“Density is an important goal, and I think that’s a direction the city needs to move in,” Andrés Oswill, the planning commission’s youngest member, said Tuesday. “I’m proud of the work we’ve done.”

Oswill said his decision to support the cap on building size had been informed, in part, by his own home search over the last few months.

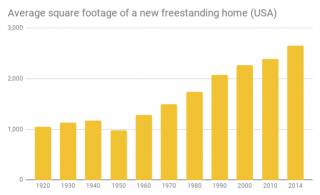

“I really struggled and tried to understand 2,500 square feet … being too small,” he said. “It wasn’t something I was able to come to terms with.”

Eli Spevak, another commissioner, agreed.

“For all the talk about We can’t fit into this 2,500 square foot house, I kind of think, well, we did for most of human history, in houses half that size,” Spevak said. “I also think about the carbon issues. Oregon has studied this more than any state. The biggest carbon impact of new construction, over the lifespan of a house, is how big it is. Seventy, 80 percent of the carbon impact of a house is heating and cooling the space. … Attached housing is great for that also, and this code supports both those things: attached housing and small homes.”

Spevak is right: North American home sizes have risen sharply since the 1950s.

In fact, that’s almost economically inevitable. As long as the only profitable way to redevelop a one-home property is to replace it with another detached home, then each successive home on a lot will be bigger than the last.

Unresolved issues: Fourplexes and displacement-risk areas

The planning commission’s straw vote Tuesday follows three years of formal debate so far over the proposed zoning reform and precedes a formal (but nonbinding) recommendation to Portland’s city council. The city council’s binding vote is scheduled for the spring.

“Even if this were just a little bit better than the status quo, that wouldn’t mean that we should wait more years rather than make these changes now and then continue to improve upon them.”

— Madeline Kovacs, Portland for Everyone

Some issues still need resolution. The planning commissioners who were present Tuesday split evenly over the question of whether to allow up to four homes on a lot.

“As we’re asking the single-family neighborhoods to transition, it’s a big change,” said one commissioner, Michelle Rudd.

Another, Chris Smith, disagreed.

“What do the neighbors have to be afraid of?” he said. “It’s buildings, people or cars. … If it’s buildings, we’ve done a lot to limit the size of buildings. … We did not allow any FAR bonus for the fourth unit. so if a building becomes a fourplex, it will not be much larger than a threeplex. … If it’s about cars, I will point out that we’ve done very little in this package to limit parking. In general, we’re still allowing people to build parking.”

So any concern about fourplexes must actually be about the number or type of people living in currently exclusive areas, Smith concluded. And “I’m for letting as many people live in these neighborhoods as we can,” he said.

Another area of debate: what effect the size or unit-count incentive might have on the rate of redeveloping lots that are currently home to low-income people, and if so how to mitigate that. Oswill said he regretted the “missed opportunity of having funding streams be created out of this that could lead to equitable units or programming.”

The city’s initial plan had proposed extending the duplex-triplex ban in areas with the highest risk of displacement. But affordable-housing advocates unanimously told the planning commission that they disagreed with that approach, because it would fail to create new housing while leaving those areas just as vulnerable to one-for-one redevelopment.

“The anti-displacement folks told us the right way to limit displacement is not to limit development opportunity but to deliver anti-displacement programs where they’re needed,” Smith said. “The question I still worry about is, well, what happens if council doesn’t fund any of those programmatic solutions?”

Madeline Kovacs, coodinator of the pro-housing Portland for Everyone coalition, said Thursday that she had the same concern, but that extending the duplex-triplex ban would only lead to more one-for-one displacement while the city waits for political consensus around more funding.

“We know what’s happening in Portland’s neighborhoods right now,” Kovacs said. “Even if this were just a little bit better than the status quo, that wouldn’t mean that we should wait more years rather than make these changes now and then continue to improve upon them.”

In the end, that’s the only way any major rethink of Cascadian housing policy will happen: bit by bit. But if anything is going to change at all, it’s going to depend on people choosing to show up and tell one another what they want—one public meeting at a time.

— Michael Andersen is a senior fellow at Sightline Institute

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

When are we as a state going to move to a Sales Tax and do away with Property Taxes…

Yeah! Screw the poor!

https://www.citylab.com/life/2015/01/how-local-sales-taxes-target-the-poor-and-widen-the-income-gap/384643/

Very Rarely are Sales Taxes a substitute for Property Taxes. In most states they replace Income Tax. What we really need is Henry George’s Land Value Tax, that taxes all gains in the price of land and also levies taxes against unused or unoccupied property. In his book “Progress and Poverty” Henry George predicted all the problems we have with the economics of real estate in our country and he did it 125 years ago. The bankers of the guilded age buried George’s ideas because there was easy money to be made in buying and selling real estate, now the wrong fork we took is obvious.

Plenty of states in any direction you care to head that will allow you to pay sales tax if you miss it so much, you can turn right around and go back.

Yeah, and they provide better services too.

Where is any discussion of limits?

I love duplexes and triplexes and infill as much as the next person—would much prefer to live among such structures, that density—but when it comes to carbon this is hardly a plausible way to count things. If we’re concerned about carbon we need to figure out how to STOP BUILDING, STOP GROWING. If density is embedded in some serious discussion of limits then we may get away with invoking carbon, but otherwise this pitch strikes me as an opportunistic scam.

considering that portland’s urban growth boundary is poised to increase by 2200 acres, increased density on existing developed land is hardly a scam. my main criticism of this form of very low density housing is that it is does little to address our chronic affordable housing shortage or our desperate need to decarbonize land use.

20 story coop apartment buildings and de-paving of sub/exurban on the other hand…

“20 story coop apartment buildings and de-paving of sub/exurban on the other hand…”

Maybe a little closer. But, again, without putting limits front and center in any discussion, density solves nothing w/r/t carbon budgets. Growth, whether dense or not, is the problem, the thing we need to come to terms with.

“without putting limits”

in my experience, “let’s limit growth” folk often want to eat their low-growth cake in smallish bungalows…

How about engaging the issue of growth, instead of jeering from the sidelines?

my comment specifically criticized expansion of the urban growth boundary and called for de-paving suburbs (e.g. shrinking the UGB). that’s pretty anti-growth, is it not?

OK, I guess that reading makes sense, though I feel like I’m hearing you talk out of both sides of your mouth.

I have yet to see a city council or a planning commission that isn’t dominated by individuals in the real estate or building trades, people who benefit from continued growth.

I have however seen many cities stop or even reverse all growth by:

– Failing to deliver basic services such as crime prevention, sidewalks, bikable streets, transit, etc.

– Engaging in growth strategies that constantly expand boundaries, such as annexation, building freeways and bypasses, thus stretching already vulnerable services ever further.

– By engaging in collective NIMBYism and doing everything except being bold and progressive.

As long as any city like Portland continues on its present strategies of being bold and progressive in land use policies and growth, providing increased services to its most vulnerable users, and trying to do more with less, Portland will continue on its current awful path into purgatory to relentlessly grow without building new freeways or annexing its neighbors.

Shame on Portland for striving to become one of the leading big progressive cities in America.

“Portland will continue on its current awful path into purgatory to relentlessly grow without building new freeways or annexing its neighbors.”

Laugh all you want.

Your scorn doesn’t get you off the hook, excuse you from explaining how exponential growth on a finite planet is supposed to work over time.

Is it possible to discuss a voter boycott of all candidates for local public office who have an occupational background in real estate? Local public offices–by that I mean state legislatures on down to city councils–a large percentage of the things they vote on are land use related. If someone has been a realtor, broker, contractor, even a carpenter before taking a city council seat, for instance, they are in conflict of interest, aren’t they? People raised hell about Vice President Cheney’s oil biz background–to me, this is every bit as bad. People who make money selling or building properties shouldn’t hold local public office, the corruption is hard wired in.

Having experience in an area is much different than having an ongoing financial interest. The proper way to handle such an interest is to recuse yourself from participating in making a decision which could benefit you or your family members.

PSC officials should follow this practice.

To my knowledge there is no plausible decarbonization scenario that doesn’t involve (a) significant rates of redevelopment and (b) Americans living significantly closer to one another and to their destinations. As long as we’re already getting (a), then we had damn well better be moving toward (b) or else we’re just digging ourselves a deeper hole. (And if we weren’t getting (a) at all, that’d be a whole other problem.)

I think we agree that this set of measures would not in itself achieve sustainable energy consumption in Portland. But it is currently literally illegal for Portland to achieve sustainable energy consumption. Legalizing sustainability is insufficient, but necessary.

I don’t disagree with Soren’s point that this is a half measure. For both housing affordability and sustainability, we also need to simultaneously push for more four- and six-story buildings where possible, IMO.

Michael,

we have an accounting problem.

Decarbonization, properly understood in our present circumstances, doesn’t have a denominator. Some have suggested we’re on the hook to reduce total anthropogenic carbon emissions by ten percent per year. To get to 90% of 2017 emissions in 2018 (and 81% in 2019 and 73% in 2020) we need to take certain (exciting, drastic, unfamiliar) steps, calculate our progress with reference not to some ratio but to a total.

If (thought experiment) all of Portland’s current population were persuaded to move out of their single family homes, and move into (new) duplexes, our emissions would likely rise (new houses suck up enormous quantities of resources, emit vast GHGs). Holding population and consumption in this new distribution constant, we might amortize the materials invested in those new structures over a few decades, though I doubt this would set us on a 10%/yr reduction trajectory. But if we did this WHILE CONTINUING TO ENCOURAGE IN-MIGRATION, no amortization would ever occur, no carbon benefits would accrue. The climate isn’t interested in ratios, in how many people we divide our emissions by. The only number I can take to the big climate bank in the sky is total emissions. Most everyone who weighs in on this matter of density and carbon in these conversations here seems to willfully deny or be unaware of this basic accounting distinction.

“To my knowledge there is no plausible decarbonization scenario that doesn’t involve (a) significant rates of redevelopment and (b) Americans living significantly closer to one another and to their destinations.”

Those two strategies are familiar enough, common sense approaches to reversing foolish things we have done in our exuberant pursuit of denying limits. But they don’t amount to a strategy that captures our carbon predicament, translates into what is necessary to actually REDUCE our emissions. To reduce we need to… reduce… by measuring not what happens at the individual, household, or block level but the aggregate, the total.

If we take Portland or Multnomah County or Metro as the jurisdictional unit of measurement, then we can assess whether a pursuit of density might yield the carbon reductions folks here keep suggesting. Driving less and having fewer square feet of conditioned space per person are both sensible—perhaps necessary—but without placing a discussion of hard caps front and center they are not sufficient, and worse, will give folks eager for good news the false sense that they are the solution.

We could talk about how to shrink our direct residential carbon emissions by 50-90%, without building any new structures; by adjustments, tweaks to habits, end uses, modest physical changes involving more insulation, switching to bikes, jettisoning the car, etc. but if growth is encouraged all around us, built into the system, understood as necessary, any reductions will quickly be gobbled up by additional demand.

>>> literally illegal for Portland to achieve sustainable energy consumption <<<

Can you explain that a little further?

I assume Michael meant to write ‘illegal for Portland to build at higher/medium densities,’ which of course bears no obvious or necessary relationship to ‘achieving sustainable energy consumption,’ as commonly understood.

Yes, that’s exactly what I meant. But if 9watts believes that “driving less and having fewer square feet of conditioned space per person are both sensible—perhaps necessary” for decarbonization, I’m struggling to understand why the single most influential factor in getting people to drive less (residential density) or the crucial economic factor that allows properties to redevelop with fewer square feet of conditioned space per person (residential density) would bear no relationship with decarbonization.

I could be wrong, but I think my disagreements with 9watts are:

1) he sees incremental reductions in energy demand per person as palliative, reducing political will to accept significant energy price increases or some other form of rationing; I see them as necessary steps to increasing the constituency willing to support significant energy price increases or some other form of rationing

2) if I’m reading him right, he sees migration to a region as something that can be meaningfully controlled by politically feasible domestic policy changes; I see those changes as some combination of impossible and unfair. In my view, people seeking to move somewhere will generally find a way to do so. (This includes people from Bangladesh and Phoenix, of course, fleeing the damages of climate change.) When they move here, they are slightly accelerating the day when the lowest-value homes in their former region fall off the market … just as they either (a) drive prices up here, if we don’t build sufficient housing or (b) accelerate the day when the next higher-value+energy-efficient home is built here, if we do build sufficient housing. As long as this migration is happening, we should be taking every opportunity to let our population sort into more compact neighborhoods and homes AT THE VERY LEAST to the extent that they want to.

Our current policy is to make it illegal for lots of people to live in more compact spaces and neighborhoods even if they want to. That’s dumb!

In addition to the two sustainability benefits of denser housing that Michael mentions, denser housing also typically shares at least one exterior wall with a neighbor. Assuming that the neighbors are both heating their homes in the winter (or cooling in the summer) there’s no energy lost between adjacent homes. For this reason attached housing will always be more energy efficient than detached housing built to the same standards.

I once lived in an apartment with rather low energy efficiency standards. We let our neighbors heat our apartment in winter. Warm walls all around!

Thank you, Michael, for taking my call. 😉

You wrote:

“I’m struggling to understand why the single most influential factor in getting people to drive less (residential density) or the crucial economic factor that allows properties to redevelop with fewer square feet of conditioned space per person (residential density) would bear no relationship with decarbonization.”

For three reasons.

(1) Because all of this presumes ADDITIONAL PEOPLE, is understood in the context of exponential growth that will undo any salutary effect in short order. I fully appreciate that in our time and place it is hard to talk about demand, population growth, limits, etc., but living with the effects of catastrophic climate change isn’t going to be a picnic either. If carbon is your concern—and it wasn’t me who brought this up in relation to housing—in addition to the problem of growth you are (2) focused on the wrong scale, and (3) fifty years too late.

wrt (2) let us imagine that duplexes enable a 50% average per capita drop in carbon emissions from heating and cooling and driving once the embedded carbon has been amortized. I suspect that is high, but OK. And let’s have 50% of the housing stock split reborn as duplexes. How long before we (Metro) are back to our previous carbon emissions, with no attention to the total, a cap? Will it be before we’ve amortized the embedded materials? I suspect yes.

(3) The effects of catastrophic climate change are not going to wait for us to screw around for another 60-100 years, nibbling ineffectually at the margins.

I think other examples where we have taken the same (indirect) approach may be illustrative:

CAFE standards have focused on a ratio (mpg), as have our municipal solid waste policies (increase recycling rate as share of total MSW). In both cases—and there are many similar if less familiar examples—the policy lever has drawn our attention to a RATIO that bears an indirect relationship to the first order matter we’re ostensibly trying to fix, which is A QUANTITY: total fuel consumption, and aggregate tons heading to the landfill. If I have my figures right, the consumption of fuel and the quantities of stuff headed to the landfill have not dropped alongside ~forty years of these policies. There are many reasons for these outcomes, but it is I think important to acknowledge how this works in practice. I see the policies you are proposing as taking us down a similar path: plenty of interesting results, and reasons to do this, but no reduction in carbon emissions.

Going with these policies targeted at second order effects—and I think everything points in that direction—forecloses other options. In the case of the ill-begotten Street Fee, had we gone with it this would have made it not just unlikely but inconceivable that we would, say, push for and pass a carbon tax in the short to medium term. We use up political capital, resources, and time advocating for policies that are not adequate to the task, that are not aligned with the overall goals. And drawing attention to the problem in the manner they do also misrepresents the gravity of the problem to the public.

Build more and denser, and we can solve our carbon problem.

Advocating for something that may be a wash, or could net us a few percentage points in a decade or two is problematic, when what we need to be doing is coming to grips with the fact that no amount of tweaks to business as usual is not going to solve this. At first blush all of these policies might strike as as salutary, as prudent steps in the right direction, but if after decades of targeting second-order effects, with nothing to show for it (nothing in terms of the first order problem), isn’t it fair to ask whether there might not be a more direct, more promising way to tackle this?

“migration to a region… controlled by politically feasible domestic policy changes… impossible and unfair.”

I hear you. And I don’t think this is a fun or easy topic to wrestle with, much less to codify. And there are certainly other angles to tackling limits to growth that may be less fraught. But the net effect of shying away from grappling with these difficult matters—from ANY serious discussion of limits—is that we just postpone the eventual reckoning; postpone it until some future time when it will be guaranteed to be much more painful, produce infinitely more losers.

I’ve never understood the logic, the reasoning behind postponing this discussion. Can you explain this?

Our attitude about the Cascadia Subduction Zone Quake presents a similar example. Facing the prospects of what might happen to our infrastructure, our economy, our housing, food, water, our ability to survive, is similarly daunting, and so we focus on something else, something easier, more immediate. That is the best we can do?!

Increasing density may make it easier to achieve energy sustainability in the medium run (or it may not, depending on the energy costs of destroying and rebuilding already built structures, and the pace of development of new sustainable energy sources), but your statement is, in short, bunk.

This is great news! I hope housing supporters continue to apply pressure on city council to make sure this becomes law.

My question is why does this process take so long? If the planning commission just blessed this plan, why does it need to wait around six months to go to city council?

It’s taken the PSC a half-dozen work sessions to get through this and get to our recommendation. Staff now has to take the direction we’ve given and put it in the form of zoning code and also do economic modeling on it to make sure we’re likely to get the effects we want. We’ll then give it a final vote at the end of the year and it will go to Council in the new year. I appreciate that folks are impatient, but we want to get this right!

Portland is really lucky to have such a smart, engaged and progressive Planning Commission. I wish this whole process had been faster, but I’d also prefer that the PSC gets it right than gets it done quickly. The proposal the PSC has arrived at is a huge improvement on what was brought to them by staff.

Given the number of duplexes I see being built, I’m not sure why some people think the “missing middle” is missing.

Confidential to Chris Smith: In most neighborhoods, those that can afford a unit in a new 4-plex are probably wealthier on average than residents in the older homes they replace. So if, as you say, it’s about the people, then it’s a desire to maintain some vestiges of economic diversity.

We’re well aware of that risk. That’s behind the anti-displacement programs point in the post. It’s also why we provide an incentive for internal conversions of existing buildings (versus scraping and new construction).

But the PSC’s plan doesn’t disincentivize demolitions of existing houses nearly enough…in fact, this plan will dramatically *increase* the (already too high) number of demolitions of viable existing homes, because you will have granted a major increase in land values across the city. Additional density IS needed across the city, but that can be achieved via more ADU’s and internal divisions of existing homes. Oh, wait, but that wouldn’t enrich the corporate developers who sit on the PSC and contribute to Mayor Wheeler…

Some of the steepest incentives in this plan are in fact for ADUs (now allowing two), internal conversions (0.1 FAR bonus), and affordable units (also 0.1 FAR bonus). But the big goal here is to house more people in our single-dwelling neighborhoods, and that requires allowing a number of building forms. While dis-incenting demolitions is a goal, it’s not the most significant goal.

This was my assumption too, when I started to learn about this! But the city’s economic analysis found that this policy would generally decrease land values across the city, because the main factor behind land value is the size of buildings, not the number of homes. Two 1000 sqft homes on a 5,000 sqft lot are worth about the same as one 2,000 sqft home on a 5,000 sqft lot. (Not identical, but the building costs are higher for two 1,000 sqft homes so it comes out in the wash from the perspective of the land cost.)

But both of those options are worth less than one 4,000 sqft home on that lot, which is currently legal but would become illegal.

Allowing the size incentive per additional unit, as proposed by the PSC, would increase the demolition rate somewhat because a market-rate lot could theoretically get up to 3,500 built square feet. (For example, a 1,900 sqft main house, an 800 sqft attached ADU and an 800 sqft detached ADU.) But we can probably agree that there are only so many people willing to pay top dollar to live on that sort of lot, so even then it’s only likely to result in gradual replacement of one home here, another there … sort of like the 1:1 McMansion projects we see today but way more socially beneficial.

The proposal, as I understand it, incentivizing building the exact sorts of units we have a surplus of — high end multi-family dwellings.

Since there is no immediate need for more of these, why not push forward on the internal conversion and size limitation pieces now, and take the time needed to build support for the anti-displacement policies and craft some demolition disincentives before moving forward with policies on new construction?

I think for many people, demolitions are the biggest issue, and the proposal in front of you will only increase the pace. Moving forward without the anti-displacement policies in place makes them seem like window dressing.

If we find we suddenly need an immediate bump in the number of neighborhood dwellings, we can always add limits on short-term rentals to get an immediate increase in the number of available units.

As now proposed, the code incentives the creation of new homes between 1,000 and 1,750 sq ft, a size of unit we see very very few of built (and far from a “surplus” of).

Ironically, it is these small houses that are most at threat from demolition.

But the fundamental point still remains — why push forward on the most controversial portions of the proposal before the necessary protections are in place? Or even permit the new rules where vacant lots already exist, and disallow them where structures are demolished until a protective framework is solidified?

Most of the provisions of the proposal are strong enough to stand (or fall) on their own; I think that is how we should be discussing them, not as a grab bag of stuff all jumbled together.

Why push forward with it? Because we have a status quo that isn’t working. Single family zoning isn’t an anti-displacement measure, as some of the conversation around this topic seems to imply.

If the city council adopts the Residential Infill Project proposal it will have been nearly four years in the making. In that period we’ve seen the price of Portland homes skyrocket, pricing many people of the market, especially in the desirable inner neighborhoods. In the vast majority of the city land can only be used for one house (plus an ADU). If we end the ban on building smaller units in duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes there’s a chance that a significant segment of our population could start to afford those neighborhoods again.

If the City Council were to adopt the scale caps without allowing the additional housing types then it’s unlikely the latter would come before them again any time soon. That might be okay with you, but it’s not okay with me.

Single family zoning is not an anti-displacement measure, agreed, but it cannot be disputed that more demolitions will increase displacement.

Addressing one problem (more 1000-1700 sq ft attached housing in the R2.5 and R5 portions of inner neighborhoods for upper middle class buyers) while making another worse (displacement of those who cannot afford that new housing) may not be in everyone’s best interest. I am not arguing for indefinite maintenance of the status quo, I’m arguing for holding off on one piece of the proposal (and maybe only partially), while advancing the rest, until the worst side effects (such as those acknowledged by Chris Smith) can be addressed (through, for example, anti-displacement programs).

You make a bold claim — that allowing more plexes will allow a “significant segment of our population … to afford those neighborhoods again.” I doubt it.

I don’t know why you feel that you have only one shot at bringing this to council — if the idea is good, it could be brought forward along with the anti-displacement measures and make a compelling package in its own right. I think you are tacitly acknowledging that anti-displacement programs are unlikely to be implemented. Without them, the RIP will only hasten the economic stratification of our neighborhoods.

I don’t think it is a bold claim, at all. Try doing a search on Redfin for properties under $350,000. In the inner neighborhoods almost every search result is going to be a condominium or other form of attached housing. Many of these are older buildings, but in the handful of areas where we allow construction of new denser housing you’ll also see plexes that were recently completed. As an example, there are small condos for sale on N Minnesota and N Holman for in the $330k range. By contrast, single family houses on those street start at prices that are at least $100,000 more.

I will reiterate that, if adopted, the Residential Infill project will have taken almost 4 years from start to finish. Anybody who argues that we should just give it more time is just trying to kill it through process delay.

Looked at another way, you’ve had 4 years to work out an anti-displacement program, but are only talking about it now. Why was that not part of the project from the beginning?

I have been making comments like this to BPS staff from the get-go, so this is not a last minute stalling tactic. My conclusion is that you don’t take displacement seriously. Assuming you’re involved in the project yourself, I find your attitude somewhat dismissive. I’m not asking for “just more time”, I’m asking you to mitigate a specific harm from a specific policy that even supporters admit is needed.

Saying that I don’t care about displacement is unfair and untrue. I just disagree that this proposal is going to exacerbate displacement. The proposal makes it possible to build smaller, more affordable homes that are currently banned. I think that’s a benefit relative to the status quo where a home comes on the market and it can be demolished to build a larger more expensive home.

And to imply that the city has done nothing about displacement in the last 4 years isn’t true either. In that time the city has passed the renter relocation ordinance; passed a city affordable housing bond and put a Metro bond on the ballot; implemented a 1% construction excise tax for affordable housing; increased the percentage of urban renewal funds that go to towards affordable housing; passed an inclusionary zoning ordinance; implemented the N/NE Preference policy; and started work on the landlord rental registration program. I’m sure there are other things I’m forgetting.

Ultimately I think the Residential Infill Project is good policy, and it shouldn’t have to wait for other good policy (some of which is currently prohibited by state law) for it to be adopted.

I agree that building smaller homes is a benefit, but when new housing replaces old, it often (but not always) results in an increase in price, displacement of renters, or loss of opportunity for a lower income demographic to get a toehold in a nicer neighborhood. Maybe you don’t see that, but it doesn’t mean that those who do are disingenuous or trolling, and your dismissive attitude is indicative of a process driven by those who stand to financially benefit.

I don’t say that the city has done nothing about displacement; I say that implementing a specific policy without safeguards will make the problem worse.

Financially, RIP will greatly benefit me. My neighbors… less so, especially those who rent.

In any event, if the proposal gets through council in its current form, it will almost certainly end up on the ballot, which is probably the worst possible place to be making these sorts of policy decisions.

I don’t appreciate you implying that I support the residential infill project because I stand to make some kind of financial gain from it. I don’t.

You may not, but many on the PSC do.

I don’t think that’s a fair accusation either.

Before I made that statement, I read over the membership list of the PSC and the RIPSAC, and the two may have melded a bit in my brain. RIPSAC clearly has members with a financial stake in the outcome, which is a bit troubling, but less so than decision makers such as the PSC.

The PSC has one member who I understand is directly involved in the sort of construction being considered for expansion by RIP. I don’t know if he has recused himself or not, but if he hasn’t, he should. There are several other people involved in development/land use/real estate whose stake is less clear (and perhaps minimal), but without a requirement to disclose and recuse, it’s hard to know.

I’m going to walk my statement back somewhat — I can’t defend “many”, but I think I can defend “one, possibly more”, which is, admittedly, qualitatively different than what I wrote above.

PSC: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/635002

RIPSAC: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bps/article/544829

There has absolutely been disclosure. At each public hearing for RIP, the chair read a disclosure statement that outlined which commissioners had holdings in the zones affected by RIP.

I suspect you are specifically referring to my colleague Commission Spevak, who also served on RIPSAC. He is a developer who works on relatively small residential development projects (i.e., he doesn’t do Condo towers). His knowledge has been invaluable to the Commission in working through RIP. He somewhat uniquely in Portland does “Planned Unit Development” (also sometimes known as Cottage Clusters). Because of that unique nexus, he recused himself from the discussion around Planned Unit Development rules.

I would note that Portland actually has less potential for conflicts than many cities’ Planning Commissions because we have a restriction on having more than two people in the same profession on the Commission. While we certainly have folks involved in development, as a result of that restriction we also have an Internet Architect (yours truly), an Urban Naturalist and a Minister. We have also in recent years tried to make sure we have someone who is 25 or younger when they start their term.

Are commissioners required to recuse themselves if they have a conflict of interest?

Disclaimer: I am not a lawyer, this is my understanding as a layman!

The “controlling legal authority” as Al Gore liked to say is ORS 244 (https://www.oregonlaws.org/ors/244.020) which defines both “Actual conflict of interest” and “Potential conflict of interest”.

There’s a general understanding that since Planning Commissioners only recommend to City Council and are not final decision makers, that we probably cannot have actual conflicts of interest, only potential conflicts, which require disclosure.

Nonetheless, we pay attention to the appearance of conflict, and recuse ourselves when we deem appropriate. The decision lies with the individual commissioner, but generally there is discussion with staff and commission leadership about what is appropriate.

During the Comp Plan and Central City processes a number of commissioners recused themselves on specific topics due to property ownership or participation in certain projects or categories of projects.

Trust me, the Planning and Sustainability Commission is not a vehicle for enriching yourself. You get to give away large amounts of your productive time for no remuneration…

“an incentive for internal conversions of existing buildings”

this is not an anti-displacement policy because most of the economic eviction in portland is a result of speculative ownership change and/or “renovations”.

Please follow the advice of the Anti-displacement PDX coalition and others:

* Implement larger FAR bonuses for permanently affordable units.

* Implement larger FAR bonuses for family-scale units — and especially permanently affordable units.

* Allow additional bonus units for each permanently affordable unit (e.g. 5- and 6-plexes should be allowed if 1 or more units are affordable).

* Hold fast to the proposed amendment that applies RIP to all residential zones. Do not exclude communities of concern and vulnerable residents from needed land-use reform!

* Implement displacement risk reports in code (as described in the Comprehensive Plan) and require reviews for development that score highly for displacement risk.

* Eliminate parking requirements for all residential codes.

tear down a tiny $500,000 bungalow and replace it with a pair of 4,000 square foot units that sell for over a million…. It’s happening all over the city and we would have been better off had the tiny bungalow stayed.

Under the current proposals the maximum size of a duplex that could be built on a typical R5 lot is 3,500 sq ft; or 1,750 sq ft per unit.

what you are describing is the status quo…a truly awful situation for vulnerable tenants who are being displaced by 1 to 1 development and renovation.

I agree… that’s why I support the building size limitations. But when demolitions are further incentivized, expect the problem to get worse.

remarkably, the city’s own economic report indicated that demolitions would not change much under the pre-amendment proposal. smdh.

Except…

Such a redeveloped lot could effectively house 2 families living in the 2-plex, whereas only one family would be housed in that lot as-is. The value of the property overall may increase, but the cost to any one renter or buyer would decrease, because, if this happens all over the city, there’d be more housing to choose from. More housing = better market for buyers/renters.

The migrants are moving here, are they not? Are we going to just ask them to sardine themselves into existing 800 square foot bungalows like mine? I understand the urge to maintain and save older buildings, but I think that urge puts the values of an old building over the values of keeping our growing population housed. Do we really want to become San Francisco?

I personally know a number of people who moved here from the Bay Area because our housing is cheap (comparatively speaking). Some even continue to work at their old jobs remotely.

Our underpriced (from a west coast perspective) housing will continue to induce demand until the larger market has reached an equilibrium. Do you suppose we can outbuild that demand?

“Do you suppose we can outbuild that demand?”

Nope. And the all too predictable attempt to do so anyway gives me the willies.

there are no limits on building outside of the UGB and the UGB will be expanded so the status quo is no impediment to “growth”.

The whole point of the UGB is to limit building outside of it.

the ugb is a buffer area that limits growth around the portland metro area. outside of this zone there is little impediment to suburban and exurban growth. moreover, the UGB is poised to grow again by 2,200 acres.

https://www.oregonmetro.gov/sites/default/files/2016/10/21/UGBhistory.pdf

Could you perhaps explain the nearly complete lack of suburban/exurban development outside the UGB? Why would developers want to expand the boundary if it meant they now had less freedom to build in the annexed areas?

Have you visited Vancouver, Camas, Sandy, Battle Ground, Canby, Washougal, Ridgefield, Sheridan, Oregon city area, Forest Grove area etc lately?

The UGB paired with exclusionary zoning has helped disincentivize close-in development while incentivizing the least sustainable type of sprawl.

The UGB does not apply to Washington.

Maybe I’m wrong, but I suspect that people do not move to Camas looking for opportunities to lived in multifamily attached housing. Your claim that they are only there because of zoning rules rings hollow. More likely they are there because they want less density than is required in Portland.

So I take it back. Maybe you are right that as we make our zoning exclude different types of housing, places like Camas will become more popular.

“Do we really want to become San Francisco?”

So tiresome, the San Francisco bugaboo. I refuse to be strong-armed with the same old cliche.

Can’t we trust ourselves to be more creative, figure out ways to tackle and solve these problems? Why are there always only two crummy choices?

given portland’s racist and classist residential zoning code, i think palo alto is a more apt analogy than san francisco.

What makes San Francisco’s zoning less “racist” than ours?

much of portland’s urban core is zoned for single-family-homes because wealthy white folk wanted/want to keep poor people and people of color out of their neighborhoods. most of the urban core of san francisco is zoned for multifamily housing.

SF has profound problems with lack of affordable housing but these could be solved by higher taxes and a significant public housing build out (as has been done successfully in multiple cities in wealthy anglo-euro nations). once again rich people are the impediment but in a different way from portland.

Just so I’m clear on how zoning works, single family housing = racist, multi-family housing = not racist. Is my understanding correct?

In general, I find it quite helpful to have radicals on the left make complex issues so easy to understand.

“But this hardly ended racial discrimination in housing, as whites adopted biased policies like economic zoning that banned apartment buildings in areas designated for single-family homes, often adding minimum lot size requirements to boot. Because African-Americans were disproportionately low-income, economic zoning was in effect exclusionary, accomplishing much of the same results as explicit racial zoning.”

“Developers challenged economic zoning in the courts, but with a different ultimate result. In the case of Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty, a federal court struck down a zoning ordinance in a Cleveland suburb that prohibited apartment buildings in an area zoned for single- and two-family homes. The court noted that “the result to be accomplished is to classify the population and to segregate them according to their income or situation in life.”

“But when the case reached the Supreme Court in 1926, the justices declared that excluding apartment buildings was constitutional. In language laden with class bias, the court reasoned that an apartment house can be “a mere parasite, constructed in order to take advantage of open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/03/opinion/sunday/zoning-laws-segregation-income.html

By this logic building codes, labor unions, and steel tariffs are also racist because they drive up the cost of new housing.

first of all, the idea that unions (or some random tariff) necessarily increase the cost of houisng is very suspect. secondly, exclusionary zoning laws are designed to target or segregate a particular neigbhorhood (unions, on the other hand, are non-geographic).

My reading of the zoning rules is that they are race neutral.

That they restrict some forms of housing in some areas doesn’t make them racist. That people who held racist views in the past supported zoning does not make it racist. That you don’t like zoning rules doesn’t make them racist.

By labeling everything racist, you distract from having a substantive conversation about the underlying issues, such as the threat continued demolitions (also not racist) have to the single most affordable type of housing, which is shared housing in older houses.

Because people of color have disproportionately lower-income, exclusionary zoning was

and is designed to have “much of the same results as explicit racial zoning”.

We can pass this and the reality is that it might add the same number of units in a year that are added in just one apartment complex. The big difference is that the duplex that gets built in Laurelherst or Westmoreland won’t be someplace most of us can afford, it will end up not being rentals, but will be sold for well above the average for the neighborhood.

Pass it then we can move on and actually find a solution, but a few hundred new units is a drop in the bucket.

I agree this is only a partial solution in the best case scenario. But you’re saying a 1,500 sqft duplex unit in Laurelhurst (the maximum market-rate size allowable under the planning commission proposal) could sell for more than the average price of a home there — must be like $750k? Home prices here are nuts but I don’t think they’re that nuts yet … and if they ever become that nuts it’d be because the average price of a detached home in Laurelhurst would have crossed $1m.

The 1924 downzone of Laurelhurst and Eastmoreland has lasted for almost 100 years. This policy may well remain for another 100 years. We should be planning not just for current economic conditions but for the city we want the next several generations to inherit (hopefully not literally :).

Portland is a very expensive neighborhood to live in…

Yeah, that’s why I moved. Sure my new community sucks in many ways, but at least the rich property owners pay higher property tax rates, usually twice or more per $100,000 what owners in Portland pay. State income taxes here are very low (5.49% after a generous standard deduction) and sales tax is modest.

As the owner of two corner lot homes , I feel like I just won the lottery. 🙂

Just remember, if you build an ADU or divide a house, they will reasses your property taxes. For some properties, it could more than double.

But Chris, even if the taxes double, they are still a bargain compared to most of the USA, where property taxes are far greater as a percentage of value than they are in Oregon (or California, another low-property-tax state.) As long as your property tax rates remain low, and they probably will for the next 100 years, you will always be indirectly subsidizing property-ownership at the expense of renters, who pay for lousy Portland public services through (mostly) their constantly increasing water and sewer rates.

Our income taxes are a bargain compared to much of the developed world, and yet, bargain or not, few are clamoring for higher taxes.

(And I don’t buy your subsidizing argument either — raising property taxes would hit renters as well, except where landlords eat the increase, and it’s not clear that higher property taxes would reduce water rates.)

Property taxes are the most progressive type of tax, as they generally hit rich people more than poor people. Poll taxes like your insidious arts tax are the least progressive/most regressive. Sales taxes are generally the next worse, especially those on foods (for example SD & WV). What you say about income taxes is true on the Federal level, but NC income taxes are pretty low, but not as low as Washington state or Texas which have no state income taxes. Oregon has relatively high state income taxes, extremely low property taxes, and no sales tax.

My subsidy argument holds true in part because Oregon will never raise property tax rates, ever. Your point of “if they did” is purely academic. The fact is it will never happen. Nor will a sales tax ever be imposed (and I’m sincerely glad of this.) However, certain local services must be provided and they have to be paid for somehow. In my community, replacing and maintaining water lines, sewers, and the roadways/gutters that cover them is paid partly with utility rates and mostly with property taxes. In your community, nearly no property taxes pay for water or sewer repair/replacement, since so little is collected and most of it goes towards police, fire, parks, etc. Instead, you stick it to existing users, most of whom are renters, to pay for past developers’ poor decisions on water and sewer maintenance decisions in leafy rich neighborhoods. And of course Oregon and national drivers have to pay for your $1 billion street maintenance backlog through gas taxes and income taxes that you stopped maintaining in 1992 because you didn’t want to pay the needed high property taxes.

I have mixed feelings about a sales tax. I really like not having one, and they’re generally regressive, but they would greatly help minimize the swings in revenue that destabilize government, and they discourage consumption, which is an environmental goal I strongly support.

I disagree that property taxes are progressive. In many cases they are, but they hit older people on fixed incomes particularly hard. Many people are “house rich, cash poor”.

I agree with your outlook on the potential for changes in either of these taxes, but don’t follow your argument that somehow people in “leafy” neighborhoods bear some special responsibility for water and sewage rates.

And ironically. we have Property Tax Control for landlords and homeowners but Rent Control for tenants is preempted at the State level. Hopefully, this will change in 2019.

Before you panic, Steve, Chris I is likely operating on outdated information. You can see current info about ADUs and taxes here:

https://multco.us/assessment-taxation/accessory-dwelling-units

https://accessorydwellings.org/2016/04/27/the-second-coming-of-detached-adus/

I support adding density across the city, and I don’t agree with the voices who want to preserve exclusively single-family neighborhoods. *However*, there are many possible ways to achieve that. The PSC– which includes multiple developers with declared financial conflicts of interest–took a proposal that had already been dramatically altered from the charge given to RIPSAC (*reduce* demolitions of viable homes and displacement while adding new density in specific areas), and made it enormously more profitable to those developers and realtors. This is corporate welfare, plain and simple. If this were any of the other large West Coast cities, developers like Eli Spivak would have been required to recuse themselves from the process entirely. Portland stands alone in allowing the direct beneficiaries of these policies to literally design those policies themselves.

The disinformation surrounding this Residential Infill process, the ad hominem attacks on purple concerned about demolitions, and the cozy relationship between developers, PSC staff, and Wheeler’s office, have been very disturbing to see.

There are multiple ways to get added density. I believe that the city council owes it to Portlanders to choose the policy option that does the least damage to the diverse and beautiful texture of our physical neighborhoods, while still adding needed density and new units of many sizes, and which will generate the least possible level of conflict and antagonism. The PSC’s proposal fails on both counts. Developer advocate groups like Andersen’s P4E want us to believe that it’s their way or nothing. I can only hope that city council will see more nuance than that.

An aside on “decarbonization”:

In the late 1970s California produced a “Passive Solar Energy” design handbook, done by a brilliant architect and an equally brilliant engineer, that demonstrated how to build modest and efficient single-family dwellings in every climatic zone of that huge and varied state. The technique was advanced computer simulations, focused on ordinary building materials and methods.

Jerry Brown was in his first stint as governor, but the “California Passive Solar Handbook” had zero effect on any kind of housing in the state.

It is a common error that energy for heating and cooling cannot be greatly reduced by careful and well informed design. The great fallacy is the “This Old House” syndrome, in which one designs anyway one wants, adding huge extensions –monster kitchens are obligatory–and then installs a plethora of “energy efficient” mechanical and electrical equipment .

A “Portland Efficient Housing Handbook.” would be of great utility.

+++

My friend Piper and I used to own that duplex! By teaming up we were able to get a toe in the door to homeownership. I lived upstairs. She lived downstairs. My portion of the downpayment appreciated enough to make a downpayment on a modest single family home in a less central neighborhood several years later.

Wow. 1465 square feet. That’s 465 square feet bigger than my home (family of 4). The biggest thing I always see missing from this affordable housing discussion is efficiency. there’s a lot of great work being done on the subject, little to none of it by this cities housing non profits. I’m a huge fan of attached housing (live in it), and townhouses are the way to go. Taxpayer dollars to build them and rent them, not so much.

“little to none of it by this cities housing non profits”

this is untrue and i say this as someone who is not a fan of low density townhouses/attached housing.

http://pcrihome.org/archives/tag/new-homes

Because people of color have disproportionately lower-income, exclusionary zoning was designed to have “much of the same results as explicit racial zoning”.