Whatever transportation funding package emerges for the Portland region, it’ll include a lot more than three freeway expansion projects and one transit project. Why? Because all seven members of Metro Council — including president Tom Hughes, just said so.

In a letter released yesterday (PDF), Metro offered a resounding endorsement of the views expressed by nine regional advocacy groups. Those groups, part of a nascent and broad-based transportation reform coalition, shared a letter with Metro (and TriMet and Metro’s powerful JPACT committee) about major concerns with the direction of a regional funding proposal. In that letter, the leaders of AARP Oregon, OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon, Oregon Walks, the Welcome Home Coalition, the Safe Routes to School National Partnership, and others — said they would not support a funding package unless it prioritizes equity and affordable housing while making active transportation investments commensurate with freeway capacity investments

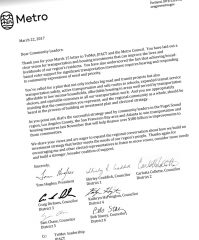

Here’s the text of Metro’s letter:

Dear Community Leaders:

Thank you for your March 15 letter to TriMet, JPACT and the Metro Council. You have laid out a clear vision for transportation and housing investments that can improve the lives and livelihoods of our region’s residents. You have also underscored the fact that achieving broad- based voter support for significant transportation investment requires hearing and responding to community expressions of need and priority.

You’ve called for a plan that not only includes big road and transit projects but also transportation safety, active transportation and safe routes to schools, expanded transit service affordable to low income households, affordable housing in areas well served by transportation choices, and equitable outcomes in all our transportation work. And you are appropriately insisting that the communities you represent, and the regional community as a whole, should be heard in the process of building an investment plan and electoral strategy.

As you point out, that’s the successful strategy used by community leaders in the Puget Sound region, Los Angeles County, the San Francisco Bay area and Atlanta to win transportation and housing measures last November that will help finance over $180 billion in improvements to those communities.

We share your views and are eager to expand the regional conversation about how we build an investment strategy that better meets the needs of our region’s people. Thanks again for encouraging me and other elected representatives to listen to more voices, consider more needs and build a stronger, broader coalition of support.

Advertisement

This is a subtle but powerful letter by Metro. I often say electeds get to choose who they assign power to — regardless of that group or individual’s actual power (for instance, the City of Portland can give one loud business owner veto power over a project simply by choosing to give that business power even if they don’t have it/deserve it). This is a case where Metro has just given this coalition much more power. Note how they refer to the coalition members not as “advocates” but as “community leaders.” Metro also cleverly repeats the main points of the coalition’s letter in a way that essentially makes them their own. Phrases like, “you have laid out a clear vision,” “you have underscored,” “you are appropriately insisting,” “as point out,” and “we share your views,” are very strong praise that adds considerable heft to the coalition’s views.

The Street Trust’s Policy Director Gerik Kransky, reached by phone this morning, said he was, “Frankly, a little surprised to see all seven members unanimously sign the letter.”

“We’re thrilled to have regional elected leaders stepping forward as partners,” he said. “They heard us loud and clear and they agree with our approach.”

Kransky said the coalition’s letter “took the conversation public,” allowing stakeholders to respond outside of any legally binding process. Hopefully that frees up other elected leaders copied on the letter to share responses of their own. Stay tuned.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

BikePortland is supported by the community (that means you!). Please become a subscriber or make a donation today.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Wow. …Good “wow”—I can’t wait to see what this materializes into.

Maybe we’ve hit upon a good strategy with having several reasonably diverse advocacy organizations present a united front; thanks to all of them for the work put into this.

Forget any freeway expansion except for caps over freeways and freeway removals.

uh, no. They still have a responsibility to enhance and improve automobile travel.

You are literally saying “My way or the highway”.

The highways are already there, in abundance. It’s the “my ways” that are currently missing from the region in any kind of comprehensive, all ages and abilities networks…

And we are getting some. To automatically say “no” to any kind of expansion is close-minded. Some expansions might be deleterious, and some might be beneficial to improve choke points.

The most congested point on any highway is the “choke point.” When you expand I-205 at West Linn, the I-205/I-84 interchange will become even more congested than it is now, and it’ll probably be the new “choke point”. Expand that “choke point,” and three or four more subsequent chokepoints in the 2020s and early 2030s, and then in 2035 ODOT’ll be asking to expand the “choke point” at the newly 3-4 lane West Linn portion of I-205. I’m not convinced that any freeway expansion reduces congestion on net in metro areas Portland’s size or larger because of sprawl and induced demand.

You are stating that you don’t believe removing chokepoints will reduce congestion because it will only shift the problem to other chokepoints and any reductions in congestion will be absorbed by induced demand.

Do you also believe the converse, that introducing new chokepoints would also have no (long term) effect on congestion because they will relieve existing chokepoints and all extra traffic will disappear with negative induced demand?

Yep, I think so (at least in the medium-long run, and in a hypothetical “What would traffic in 2025 look like if Portland had never fixed the West Burnside landslide vs. what does it actually look like in 2025 assuming they do?” framework). I mean, don’t get crazy… if we took away half the lanes on arterials and freeways in the Portland metro area, and don’t use them for bus lanes or bike lanes or something else awesome, just blow them up, yes I think congestion would be worse in 2025 or 2030 than it would have been otherwise. But if you’re talking smallish changes to the highway system adding or taking away auto capacity from what we have now? Yeah, I think limited expansions or contractions in auto capacity are matched more or less 1-for-1 by decisions to live further away from one’s work/school, to go shopping at rush hour rather than another time, to take the job on the other side of the metro area, to sign one’s kid up for that extra activity even though practices are 10 miles away at 6:30pm Tue/Thu, etc.

I’ve lived in the DC and LA metro areas my whole life before Portland and have seen multiple highway expansions fill up “so much quicker than anyone thought!” The only exception is toll roads. Toll roads always come in under the traffic projections. I’ve never been on a busy toll road (bridges yes, lengthy roads with free parallel alternatives even though they take significantly longer, no).

You seem to be arguing that there is an inherent “friction” to travel that is increased by congestion, and that when that friction changes, people who see their “travel utility” passing over a low or high threshold will decide to change their travel patterns accordingly, keeping the friction at a fairly steady state. That is, increasing the friction causes people to stop traveling, and decreasing it encourages people to start.

If this is correct, it also suggests that the “acceptable” amount of friction is increasing (and the roads are therefore becoming more congested).

It also suggests that we could slowly scale back the road network; as a thought experiment, what would happen if we closed a lane on I-5 and I-205 as it crossed the Columbia? Would that have long-term consequences to the traffic?

I don’t know that choke points can be removed, but they can be smoothed out so traffic through them rolls more smoothly. Less backups, less stressful driving. Doesn’t mean they’ll enable posted mph speed limits during rush hour. The Hwy 26/Hwy 217 intersection is an example. That used to be a ‘T’ intersection, but was changed to a big, wide radius for north bound to west bound traffic. More or less eliminated stop and go traffic, but traffic from 217 can tend to move very slow during rush hour…and when it loops around and heads west, it faces a jam packed Hwy 26 for miles down the road.

I think it was ok to improve that intersection for what it was able to do to for a moderate resolution of traffic congestion, but I wouldn’t consider what was done, to be freeway widening. Freeway widening, to me, is for example, taking a four lane highway or freeway (two lanes in each direction.), and doubling,etc, the number of lanes to say, eight lanes. I doubt that’s going to happen in our area anytime soon. As if doing so could actually resolve the traffic congestion looking everyone smack in the face. Even simple numbers make it plain, that such a strategy isn’t going to be able to suffiently reduce motor vehicle traffic congestion.

In theory, I like your definition of “choke point relief.” But in the current discussion, it’s the definition being used in the main narrative. One of the three “choke points” under discussion is a six-mile stretch of I-205 in West Linn / Oregon City that is two lanes and the proposal to “relieve the choke point” is to widen the freeway to more lanes. Another of the “choke points” under discussion is the I-5/I-84 interchange and the proposal is to add lanes there too. I forget what the third “choke point” is but I’d bet $20 that the proposal is to add freeway lanes there.

I’m not against things like you describe, necessarily. But the fact is that “relieving a choke point” in the current political discussion is being used synonymously with freeway widening (albeit along a stretch of the freeway, not the whole darn freeway). Just like “replacing the old I-5 bridge” was.

Correction! It’s *not* the definition being used in the main legislative/ODOT/media narrative. As far as I can tell, “choke point relief” is currently synonymous “freeway widening of 1-6 miles of freeway.”

I think this is an excellent way to think about this problem. We could also think about the amount of use a system sees as “pressure”. When we perceive that the amount of pressure is too great on one system, we can do a few things:

* Just let “friction” take care of it (do nothing)

* Beef up that system (widening roadways)

* Throttle input to the system (odd-even day strategies, tolling, HOV lanes)

* Spread the load to other systems (boost transit, bicycling, etc.)

I know friction and pressure aren’t good analogies to use together, but it seems to me we have three main systems supporting the urban transportation load (the

NuclearTransportation Triad): individual motor vehicles, “public” transit (buses/trains), and individual non-motorized transportation . I think a worthy goal would be to make the “friction” and “pressure” formulas for each of these systems work out to be equal. Using the federal mileage reimbursement rate for 2017 of $.535 per mile, it costs me about twice as much ($10.ish) to drive my 20-mile round-trip commute than it would ($5.ish) to take transit. However, it takes an average of 1 hour round trip to drive vs. 3-hour round trip to take transit. Too much friction. It takes about 2h 15m (and a couple of extra miles) round trip to ride my bike, which is great until it rains a lot. I really dislike riding for an hour in the rain, especially if it is dark; that ends up causing friction there. So how would those friction factors become equal? Would we dedicate a lane of Hwy 26 (my main roadway to/from work when driving) to bus-only and add some frequent-service express bus, thereby increasing driving friction while reducing transit friction? My personal friction is usually schedule (not necessarily travel time, just when I leave and/or arrive), so if driving and transit both took 2 hours, instead of 1 and 3, respectively, would I just as soon take transit as drive? Maybe, depending on the transit schedule… Would I ride more on rainy days if I knew it would take just as long to drive, or would I prefer to sit in a dry car for 2 hours rather than ride in the rain for 2 hours?There are lots of ways to “enhance and improve automobile travel” that don’t have anything to do with highways.

I don’t think that’s true. They have a responsibility to plan for the transportation investments that best serve the community as a whole within the fiscal constraints we live in. Let’s start by recognizing that we have already invested a gigantic, disproportionate amount of land and resources in automobile travel, and that additional expansion seems to have diminishing returns due to induced demand and sprawl. Given that, and the high value of other potential uses of public funds, I’m not convinced that *any* “enhancements or improvements” to automobile travel that take the form of highway expansion are the investments that best serve the community given our very limited fiscal capacity.

There are other potential transportation investments (e.g., lane conversion to bus and/or bus/freight lanes, bike/ped infrastructure, tolling, transit frequency, bus signal priority, speed cameras, lane conversion to HOV lanes, etc.) that have a much higher return on investment in urban/suburban areas than further highway expansion. So, focusing on highway expansion in the Portland area seems to me to be a betrayal of policymakers’ duty to choose the best options for the communities they serve. Some of these may “enhance or improve auto travel,” some may provide alternative options, and some are honestly a long-overdue reprioritization of our transportation space and dollars away from auto travel.

Also, the underlying assumption that we even *can* continue Ever On Into The Future with Progress! (“enhance and improve”) with regards to the convenience of automobile travel seems flawed to me. We don’t even spend anywhere NEAR the amount of money necessary to maintain the auto-oriented infrastructure that we have. Regardless of one’s opinion of the value and political feasibility of the non-auto improvements mentioned in my comment above, funding maintenance to minimum required levels should *definitely* come before spending additional funds to build even more pavement (which then has to be maintained).

Let’s remember the low average levels of per-capita economic growth across the developed world for the past decade+, the near-consensus among economists that it will continue for the foreseeable future, and the forthcoming deepening demographic drag on growth and public funds due to there being MANY fewer working-age people per non-working-age person than there once were. We need to be very wise about public spending going forward. Freeway expansion is not wise, not anymore.

We’d have far more money per lane mile for maintenance if we had fewer roads to maintain. I say tear down a few highways, depave some roads, and convert half of all lane miles to be used by a mode that does not cause wear and tear on road surfaces (i.e. bicycles).

No need to depave them (plus Sierra Club would sue due to dust in the streams for the fishies). Simply change the designation from car/buses/trucks to bikes and walking only.

You do realize how utterly insane you sound, correct?

People with correct ideas, who voice those ideas long before those ideas become accepted wisdom, often seem crazy. I’m not convinced by Adam entirely, but I am convinced that our current level of auto-oriented infrastructure provision is not fiscally sustainable without quite large tax increases, and also that those quite large tax increases will be politically difficult because of the *other* quite large tax increases needed to pay for public employee retirement; medical care and social security for the vastly increasing aging population; and other pretty much mandatory government expense increases coming inevitably down the pike.

Think about nibbling around the edges of his idea. What if the City started a program like the Street Seats program, but year-round, for residential areas, and where the City didn’t charge the property owners for it – with the caveat that the City would never pave that section of asphalt (plus maybe extra towards the center if the street is extra-wide) again? We all have seen blockfaces with two sides of the street worth of parking that always have only a few cars parked. We all have seen residential streets that are considerably wider than they really need to be and thus make speeding seem comfortable.

You can think of the necessary restrictions (don’t block the gutter for stormwater reasons; some restrictions on type of use for safety, etc. etc.) but I bet it would work. Why hasn’t out-of-the-box thinking like this about reducing the number of lane-miles the City is expected to pave FOREVER even considered when the City tells us how behind on maintenance they are?

In the clinical designation of insane….Not at all.

Are you proposing that I could reserve a parking spot in front of my residence, if only I agreed the paving underneath it would no longer be maintained?

That too, I’d be cool with that. It just seems nuts to me for the City to need to pave parking lanes.

If so, I’m in. In fact, I’ll bet that proposal alone would address almost all issues related to apartments built without parking. Property owners in the residential areas could gain permanent access to the areas in front of their properties in exchange for taking over the maintenance of those areas, and either use it themselves, for parking or other uses, or even rent it out if there were demand.

Maybe they could even use the area to store their boat.

I think it would relieve a lot of that pressure. A little bit of me wants to say that property owners don’t own the street frontage in front of their house so you need to do something with the space that has some benefit to people who aren’t you, but 90+% of single-family homeowners believe we do or should own that space, so that battle is lost. Probably a small fee (like $25 or $50 annually maybe?) for using the space for storage rather than “community-building space” (seating, gardening, stuff like that) would be beneficial to keep homeowners who really don’t care that much – they have a driveway, but what about friends or whatever? – from just reserving their parking spot because “hey, it’s free…”

I think the proposal would be widely popular. Division and Hawthorne and similar business district business owners would probably fight it hard but otherwise I don’t see much potential opposition. Maybe from tenants’ groups but I think they have bigger fish to fry?

Adam H’s idea is simply a reflection of what is already occurring all over Oregon and other states that have too few dollars to build new freeways and highways, let alone maintain them. What is being proposed by ODOT is a rebuild of certain portions of existing highways, not the building of new highways (which still occurs in other parts of the US, including here in NC, alas.) Oregon is broke. So given limited resources, a huge state pension debt, a very conservative reactionary Oregon Democratic Party, and a collective inability to raise substantially more revenue, you are stuck rebuilding very few roads, patching most of the major roads you already have, and abandoning the rest. PBOT long ago stopped repaving residential streets, as have many other communities. Only Washington County has raised the revenue it needs to effectively maintain its roads.

The space we’re talking about is hardly prime “community” space; it is immediately adjacent to a vehicle travel lane, and, even on a low traffic street, it’s not where you want to be hanging out.

Vehicle parking really is a good use for such space; it provides a physical barrier between passing autos and the calmer off-street space. Allowing people to reserve space for that (or other) use really would be popular. The problem with paying a fee is that when the pavement becomes too degraded, I would just stop paying the fee, and the maintenance burden would revert to the city. Perhaps better to attach a long-term lease to the property holder, which could specify maintenance obligations and the such.

When I was a kid, I used to play in the street. Do kids today even do that anymore, or are there just too many cars now?

That, stranger danger, and a dozen other factors that have changed the nature of childhood.

But… kids do sometimes play on my street.

Children are statistically far more likely to be killed in car crashes than kidnapped by strangers, yet we as a society don’t think twice about strapping our kids into a car seat.

We don’t think twice about strapping our kids into a car seat, or wearing our seatbelts, exactly because driving is so dangerous. It wasn’t always that way — it was a huge cultural shift that came from an understanding of the risks of getting into a car. Many here did not have a car seat when they were young, and probably recall riding in cars where no one wore a seatbelt.

What does it tell you about the utility and value of a car that a mother is willing to put her most precious thing into a machine she knows full well is so dangerous?

“What does it tell you about the utility and value of a car that a mother is willing to put her most precious thing into a machine she knows full well is so dangerous?”

It could tell us what you are implying, or—and I think this much more likely—it could tell us that she, like most of us, put out of our minds the potential danger the car represents, reassuring her conscious self that she’s a good driver, always pays attention, and that those nasty accidents (sic) happen to other (kinds of) people.

Or, most likely, both.

“…and convert half of all lane miles to be used by a mode that does not cause wear and tear on road surfaces (i.e. bicycles).” adam h

Roads break down even if no vehicles are rolling over them. Weather fluctuation and groundwater flow is hard on roads. To no small extent, the good road surfaces available for bike use, are due to their having been designed for motor vehicle use. Just stop paving the roads, and I suppose eventually, everyone could resort to using four wheel drive vehicles and mountain bikes. Look out for the dust…keeping it down is another one of the benefits of paved roads.

But roadway surfaces not being used by motor vehicles don’t deteriorate anywhere near as rapidly as those that are. You wouldn’t eliminate the need for maintenance by turning roadways over to non-motorized transport, but you would substantially reduce it – and when the infrastructure eventually deteriorates to the point that it needs to be replaced, the replacement will cost a fraction of comparable motor vehicle infrastructure.

Alex is right – we can’t afford to maintain the motor vehicle structure we have. We have too many people and too little will to invest to continue to go down the road of making automobile travel cheap and convenient for everybody. The only sensible course is to wean people off of using motor vehicles and invest in less expensive, more high-volume options for moving people around.

Metro probably is mostly obligated to follow through with the highway projects, though that’s not an entirely bad thing if the improvements can help the flow of current motor vehicle traffic levels.

Resolving anticipated increases in motor vehicle traffic level, probably can’t be achieved sufficiently with the projects planned. That’s where, conceivably to my thoughts, greater focus on improvements to infrastructure for walking and biking may hold the opportunity to help quite a bit in arresting the rate of increase in motor vehicle congestion.

Maybe this is something that’s occurred to the commissioners as well, possibly accounting for their affirmation of the advocacy group’s request for what they believe is urgently needed emphasis on travel infrastructure not requiring use of motor vehicles.

Agree! And thanks Metro Councilors!

Time for 405 to come out.

…and I-5.

Loco. Estas completa mente loco. Lo siento.

At least you’re sorry about it. 😛

Well, given that the military, freight and post office would disagree…..

405 is redundant. Imagine how amazing a sunken city within a city with one lane, each direction as a shared street.

When the earthquake happens all the overpasses on I5 and 405 will collapse and the marquam will be useless. Take out the Eastbank highway from I 5 to 84 and remodel and cap 405. The entire Eastside would be transformed.

I tend to like the suggestion by, I believe, commenter GlowBoy, that involves rerouting I-5 traffic onto 405, and getting rid of the spaghetti tangle of the ugly Marquam bridge. It would further improve Portland’s waterfront aesthetics, and

405I-5 West could someday be capped for most of its length. Plus people in cars could still speed through the downtown area—at least at non-peak hours.Great!

This is great news. But like Rick, I’d favor a harder line that excludes freeway widening altogether. The roads element will only undermine steps to promote sustainable alternatives. I was really inspired by the example of the Seattle referendum presented at the Oregon Active Transportation Summit. It succeeded where previous campaigns failed because of its pure, unapologetic transit focus. The drastic recent changes in PDX call for a drastic change of approach.

Hold on now…won’t improved and expanded cycling facilities “induce demand’?

And what would be the problem with that?

I think you just tipped your hat; your parameters are showing.

Hand. . . .tipped your hand. Poker reference.

I appreciate the correction. Always good to know these things, get them right.

Which is exactly what we’d want. Induced demand on cycling facilities should translate into reduced demand on other areas of the system.

Wait, I thought the Portland Planning Commission voted to keep the I-5 project in the Comprehensive Plan because it needed to be consistent with the Regional Transportation Plan, which includes the project. Metro Council approves the Regional Transportation Plan, so haven’t they already endorsed that project?

What the conversation is getting at is that any regional funding for transportation must not exclusively focus on highways (even if they’re included in the RTP) without also ensuring we’re meeting the many other needs our region has for transportation investment and the people who need to get around.

I know. I want the people who think we should never spend another dollar on freeways (I am not among them) to realize that metro council does not agree with them.

Oh, for sure the metro council thinks some money should be spent on freeway expansion (although I’d think Bob Stacey probably doesn’t, except in edge cases). I bet a 65% majority of metro-area voters are in favor of freeway expansion, and a 75% majority of Oregon voters (though ask us to pay for it with a visible tax like a gas tax and I’m not sure you’d get a majority, just sayin’.) I’m just voicing my opinion that I think freeway expansion is a horrible policy decision and I long for a future where it’s politically feasible to defund freeway expansion. And that in the meantime, we should fight as hard as we can to limit the funding spent on it and get as much good stuff in concessions as possible in return for the freeway expansion spending.

This is a dilemma for sustainable transport advocates and their allies on the left: whether to take a hard line and reject any transport investments that include freeway expansion or to compromise, as you suggest, and go along with road projects that include some ‘greenery’ on the side. As I pointed out further up in this thread, the Seattle greens did quite well by taking a hard approach. The Sierra Club and other enviros helped kill a succession of wishy washy transport packages over years until the latest effort in 2016, a $59 billion package that was almost exclusively transit development. Their no-compromise, ambitious strategy pushed it over the top. The takeaway, according to the group that led the campaign, is that if you want to succeed you have to keep your allies happy, don’t worry about your entrenched opposition, and think big.

When thinking about expanding freeways, think of what neighbornood you want to see plowed under to do the expanding–freeways take a lot of room. Our region is short enough on housing for it to be good to do anything that cuts into it.

I’m not sure why everyone is patting themselves on the back.

I read the letter above and it begins:

“You’ve called for a plan that not only includes big road and transit projects”

The words I saw were NOT and ONLY. Looks to me like big road projects are still the first loading order. Clever.

Speaking of highways, why on god’s earth don’t we have an HOV lane all the way through the metro area, EW and NS ????

I also read this similarly. And the letter from the Metro Council just summarizes what the Advocacy Groups letter says. Then ends with:

“We share your views and are eager to expand the regional conversation about how we build an investment strategy that better meets the needs of our region’s people.”

It does not necessarily agree with the views or commits to anything. Just indicates the Council is now “encouraged” to listen to more input. To me, this letter from the Metro council is a hand wave response.

That is exactly why I am in support of the Rose Quarter expansion, it would allow us combined with congestion pricing we could make the third lane systemwide an HOV lane. These combined would mitigate any induced demand effects, encourage car pooling and shared electric vehicles, plus express suburban bussing during Commute times.

It would also set us up to move I 5 to a modernized 405 and Remove the east bank highway completely south of 84. The big earthquake is going to take it out anyway…..So we should be prepared.

Does the RQ proposal say anything about congestion pricing or HOV lanes? If not, that doesn’t seem like a very good reason to support it.

Induced demand is like global warming – it doesn’t go away because you pretend it doesn’t exist.

+1

Oh, I like the idea of getting rid of i5. No more need for a mega bridge and think of the super high priced towers that can be sold on the new east waterfront to finance the removal.