This is the second in a three-part series. Read the first installment here.

This is the second in a three-part series. Read the first installment here.

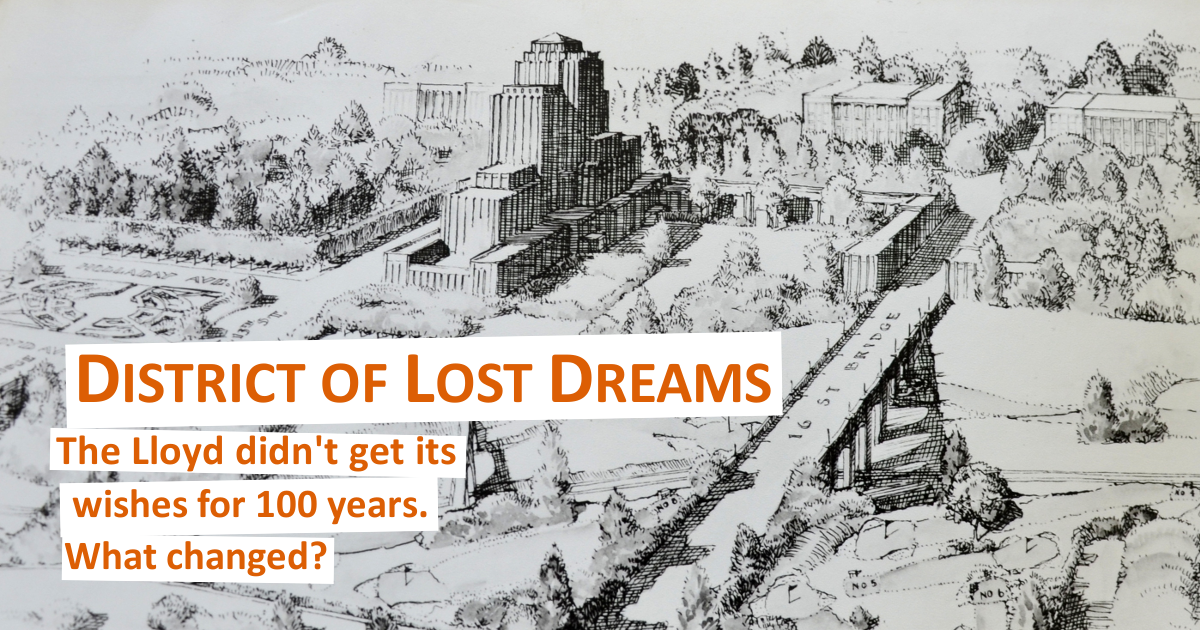

For most of Portland’s history, the land we know today as the Lloyd District was best known for failure.

Holladay Park: named for a scoundrel who planted its trees and then gambled away his fortune. The state and federal buildings along Lloyd Boulevard: advance outposts of a government center that never arrived. And Lloyd himself: an oil multimillionaire who died all but cursing the city he’d fallen in love with 40 years before.

For people who ride bikes in Portland, the legacy of those years — rolled out in acres of asphalt, traced like permanent detours onto the city’s bike maps — eventually became an insider’s joke told with a slight sneer.

“Avoid the Lloyd,” the famous homemade stickers of the mid-2000s said. “Trust an original. Go to Beaverton.”

But how did the Lloyd District become a suburb hidden in the middle of a city? And what happened as the 20th century ended that has started to open it back up — putting it on course to become what could be, 10 or 15 years from now, the most bike-oriented high-rise neighborhood in the country?

The answers to those questions tell a story about Portland, and a story about all American cities.

They also suggest a lesson that Portland, like all American cities, is still struggling to learn about itself.

The undivided subdivision

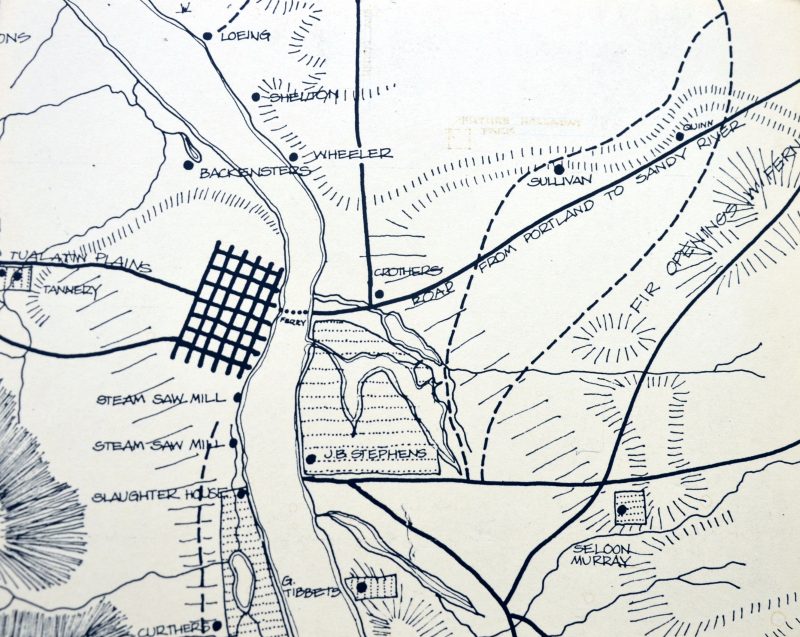

Before the land just north of Sullivan’s Gulch was named for Ralph Lloyd, it was named for someone else: Ben Holladay.

Born in 1819, Holladay left his parents’ Kentucky home for a road trip in his late teens and never came back. He hit it big before his 30th birthday with a business shipping supplies to U.S. troops in the Mexican-American War. In 1862, he bought the stations of the failing Pony Express and reinvented it as a profitable stagecoach line.

Then he moved to Portland and it all fell apart.

Railroads were transforming the country in the 1860s, so Holladay switched his business from horse carriages to steam engines. But when he started trying to develop the acres he’d bought along the gulch, the rail magnate made a fateful decision: for some reason, unlike most of Portland’s early property owners, he didn’t build a streetcar line to his land.

“He never extended any kind of transit service to this property,” said Steve Dotterrer, a Portland historian and the city’s former top planner. “There was one on Broadway, but even that was pretty late. … So as a residential subdivision, it didn’t fill up.”

Railroads turned out to be bad news for Holladay all around. He bought too many too fast and was ruined in the Panic of 1873. He died 15 years later, leaving the city a long series of bribes and brothels, and also a mostly vacant tract of land that everyone called “Holladay’s Addition” for the next 50 years.

Then someone else showed up.

The country and the city

Ralph Lloyd came from a family of Welsh ranchers. But he wanted to be a singer.

Born outside Los Angeles in 1875, Lloyd worked his way into college in San Francisco in the 1890s. He studied geology but tried making a living on his voice in the city. Lloyd stuck with it until a letter arrived from his father, saying he was needed on the ranch. At age 21, he moved back home.

He helped run the ranch for nine years. Then one day in 1905 Lloyd told his parents he was quitting to take a job at a wood-pipe factory.

His mother was baffled, but it turned out that Lloyd’s new boss was grooming him for management. Lloyd and his wife moved to Olympia, Wash., in 1907, to investigate an unprofitable factory and successfully turned it around. The next year, he was promoted to senior vice president and relocated to Portland.

The Lloyds fell head over heels for their new town.

Lloyd, 33, was convinced he had discovered the next Los Angeles. Like many people of the time, the rancher’s son thought of cities essentially as leeches that lived off the wealth of a countryside — so the lusher the countryside, the fatter the leech.

“You have an enormous hinterland from which to draw, which is bound to make this the outstanding city of the Pacific Northwest,” Lloyd wrote later.

Lloyd started pooling his savings to buy buildings in Kenton and inner Northeast. But the treasure he wanted most was the huge, weirdly undeveloped acreage known as Holladay’s Addition.

“Nowhere else on the coast can one find such a body of vacant property in the heart of the city,” Lloyd would write. “This property is bound to be valuable in the immediate future.”

Dreams deferred

No one else seemed to agree. Portland’s money had always been on the west side, people said, and that’s where it would stay.

The young pipe executive found a wealthier business partner and made an offer on the land, but the deal fell through. Three years later, his mother died and he moved back to Los Angeles to take over the ranch.

Then, in 1912, he struck oil.

The Lloyd family, it turned out, had been running cattle on the seventh-largest oilfield in California. Ralph Lloyd was 37 when the first well on his land exploded with pressure from the vast reserves beneath it. All of which made it especially convenient that, as a young man home from geology school in 1903, he’d convinced his father not to sell the mineral rights to their land.

Within a few years, Lloyd was a millionaire. And he knew exactly where he wanted to spend it.

In 1926, he bought Holladay’s Addition and 170 surrounding parcels for $1.65 million, the equivalent of $22 million today. Working from his Los Angeles office, Lloyd made plans and mailed political contributions to Portland city council members.

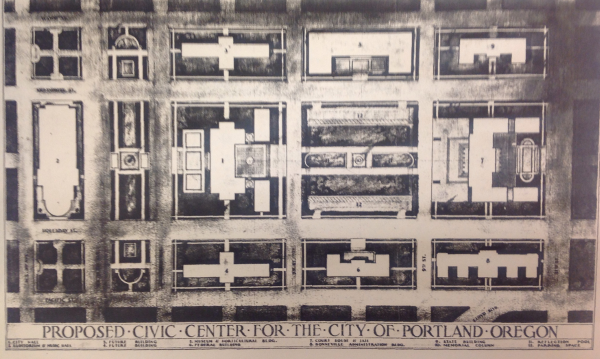

Holladay’s Addition, he decided, was destined to become Portland’s “second downtown,” a mix of apartments, shops and government office buildings in the geographic center of the city.

No bank would open a branch on the east side. Lloyd started one himself so he could borrow from it. Portland’s 200-foot blocks, the shortest in the United States, weren’t suited to the grandeur he wanted, so he decided to merge the ones on his land into “superblocks,” 440 feet on each side.

‘A strange Moloch from Los Angeles’

Lloyd had fallen in love with the city in 1911, the peak of Portland’s streetcar age. But the 1920s were the age of the automobile, and Lloyd set about making sure his district embraced it.

In April 1929, he wanted to widen the street that ran alongside the gulch to fit more traffic, but the city didn’t have money to spend. So Lloyd bought the adjacent houses himself, knocked them down and donated the land to the city. The city council named it Lloyd Boulevard.

It didn’t make him popular. “Shrubs of a few years growth were featured as helpless victims to be sacrificed before the golden altar of a strange Moloch from Los Angeles,” a local newspaper wrote of the project.

Nine adjacent property owners sued Lloyd and the city, saying he had no right to build public roads with private money. A judge agreed. Lloyd was confused.

“In Los Angeles we beg people to spend their money,” he wrote to a friend. “In Portland they enjoin them to keep them from spending it.”

Another letter, marveling at Portland’s decision not to knock down buildings to add lanes to West Burnside: “I cannot understand why the people of Portland offer so much resistance to improvements that in the long run will be so beneficial to them. It seems to me that the people of the west side in opposing the widening of West Burnside are simply committing suicide as far as their properties are concerned.”

Advertisement

A forgotten city

Lloyd broke ground on the centerpiece of his $40 million plan, a 24-story hotel just east of Holladay Park, in August 1929.

Two months later, the stock market crashed. Lloyd’s own money was in oil, but everyone else in the city stopped building. His plan collapsed.

Grass grew in the pit that was supposed to become his hotel. Musicians started using it as an informal concert venue during the summer.

Lloyd kept buying houses in the area for 20 years, still looking for his big chance. At one point, in 1937, he announced that his goal for the development was to serve the “middle class rather than the rich.” But other than a few state and federal buildings, his district never rose. No one wanted to build a second downtown between his boulevards. He died in 1953.

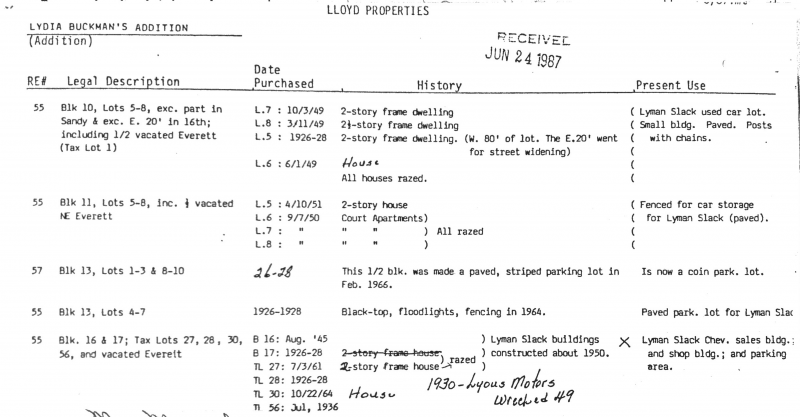

A stray purchase record from his company’s files shows the fates of a few of the houses he bought.

The district’s fortunes improved after Lloyd died.

His three daughters and their families finally finished developing a hotel; it opened in 1959. Across the street, they hired an architect of the Space Needle to design one of the country’s largest shopping malls, ringed with three stories of free multi-level parking garages to ensure a stream of customers.

They gradually found office tenants, too. The huge, undeveloped expanses of Lloyd’s district turned out to be perfect for what the employers of the 1960s and 1970s needed badly: parking lots to store the cars of college-educated workers from the newly built suburbs. Finally, a few towers started to rise.

“Lloyd office space going like hotcakes,” a 1979 Daily Journal of Commerce headline announced.

For a while, Lloyd’s notion of what a good city was — a pipe through which private cars and the harvests of the countryside could flow quickly — seemed to have arrived.

But cracks were appearing, too. An undated Willamette Week article stored in the Ernie Bonner Papers at Portland State University (which are the main source for this history) mostly praised the district’s success, but added:

The ubiquitous automobile, the lifeblood of any shopping center office building complex, dominates most human activity in the area. It even threatens the atmosphere of the center itself. For despite the construction of certain community amenities and facilities, they are separated by roads and acres of parking lots, creating a non-walkable, inhuman environment — a marked divergence from Ralph B. Lloyd’s original dream.

Death and life

By 1989, the Lloyd was considered a problem spot.

People were regularly getting mugged while walking through Holladay Park from MAX stop to mall. Local janitors kept discovering toilets clogged by drug needles. The huge parking garages, uninhibited for so much of the day, had become crime magnets; that year the district reported more than 700 car prowls, about two per day.

Office space in the Lloyd couldn’t command the premium it once had. The landowners got uneasy.

In 1995, Pacificorp, the utility that had bought most of the land from Lloyd’s children, got an offer from a 38-year-old man from Connecticut named Hank Ashforth. His company wanted to buy 17 blocks of the Lloyd District.

“What we saw from the East Coast was fixed-rail transit bisecting the district,” Ashforth recalled in an interview this month. “We understood the power of what we now call transportation-oriented development. … We own an office building right at the Greenwich railroad station, and it’s been unbelievably productive.”

Ashforth saw something else, too: the big lots of Holladay’s Addition, still mostly undeveloped.

A new direction

Rick Gustafson, a former Metro president and development consultant who has lived just north of the Lloyd for 35 years, said Hank Ashforth’s purchase set the district on a new course.

“He had pushed for his family, the Ashforth family, to modify their business model,” Gustafson said. “They buy office buildings; that’s what they have done historically, for three generations. Hank was pitching housing: residential development and mixed use.”

Gustafson said Ashforth met “enormous resistance” from his board of directors, largely his family members, when he pitched the idea of adding residential towers to a crime-ridden inner-city office park in the least interesting metropolis on the West Coast.

But Ashforth and his executive vice president, a former Pacificorp property manager in his early 30s named Matt Klein, won their argument. It was Klein, Ashforth said, who hit on the formula that would give the district the life it had never had.

Klein decided that the Lloyd District needed to start charging for auto parking, and use the proceeds to encourage transit, biking and walking instead.

Even today, the plan would probably sound outlandish to most Portlanders. How could that possibly be good for business? In 1995, Gustafson said with a laugh, it sounded even stranger.

“Maybe he was just young enough that new ideas could appeal to him, as opposed to the formulas that developers often get themselves into,” Gustafson said.

Under Klein’s guidance, the district created a transportation management association to start orchestrating the transition. (Klein left Portland in 1999 for a job with a major real estate firm in Washington, D.C. He is now its president.)

The lessons of history

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

Twenty years later, more than 100 years after a young Ralph Lloyd walked down a street that didn’t yet carry his name and imagined it as the greatest neighborhood in the Northwest, something is definitely happening.

In 2011, a different southern California company — this one called American Assets Trust — signed a deal with Ashforth to develop its properties.

Two years ago, their management company persuaded the city to remove two auto lanes from NE Multnomah Street, one of the roads Lloyd had widened, to add protected bike lanes and on-street metered parking. The main reason, executive Wade Lange explained at the time, was that people don’t tend to spend money on streets designed for speeding cars.

The mall that Lloyd’s children built is still the biggest one in Portland, but malls are on the wane across the country. After Nordstrom’s began to signal that it was pulling out, the mall’s owners sold to a Texas-based company, Cypress Equities. It’s announced plans to redevelop part of Holladay Park, remodel the parking garage to create a direct street entrance for the first time, and open a row of street-facing shops along Multnomah.

The concert pit that was once supposed to hold Lloyd’s hotel became a movie theater’s parking lot in 1987. Last month, a developer announced that he’d acquired an option to redevelop it as a 980-unit apartment-retail complex.

Earlier this month, American Assets Trust entered design review for the second of three planned redevelopment projects that will slice Lloyd’s superblocks back into 200-foot squares, reconnecting the old grid with pedestrianized streets and on-site bike valets.

Bike infrastructure, though improving, is still on the drawing board. We’ll discuss it in Part III of this series.

Many Portlanders are dubious of the district’s rapid changes. Some say the new buildings will clog streets with cars. Some say they’ll benefit only the rich. Some warn that if the Lloyd has taught Portland anything, it’s that big plans can collapse.

That’s true. And today’s might, too.

But the other enduring lesson of the Lloyd District is about more than the Lloyd District. It’s about what a city is and isn’t.

A city is not a leech. A city is not a pipe. A city is not a plan.

A city is a place.

Coming in two weeks: The bikeways it’d take to make the Lloyd great.

*This article was possible largely thanks to a biographical manuscript about Ralph Lloyd and other documents in the Ernie Bonner Papers at the PSU Library Special Collections.

— This in-depth series is brought to you by the bike-loving folks at Hassalo on Eighth, the Lloyd District development that is now leasing. We agreed on the subject of the series but they have no control or right to review the content before publication. Learn more about our sponsored content here and read all the articles in the series here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Wow. Thanks, Michael.

And three cheers for long form journalism!

Yeah, say, where’d all those sponsored content grumps go? This was a pleasure to read.

Fantastic article, Michael! This was a great read!

“By 1989, the Lloyd was considered a problem spot.

People were regularly getting mugged while walking through Holladay Park from MAX stop to mall. Local janitors kept discovering toilets clogged by drug needles. The huge parking garages, uninhibited for so much of the day, had become crime magnets; that year the district reported more than 700 car prowls, about two per day.”

But fortunately, today, there would never be gang shootouts in the Lloyd Center parking garage, right? Well, except for last Friday…

I also thought that one of the reasons why they closed the movie theater in Lloyd Center a few months ago was that so many cars were getting prowled during evening movie performances.

Looking forward to the lucky inhabitants of Hasslo on 8th discovering that the Lloyd District is pretty problematic at night, and has its moments during the day, as well.

It’s before my time living in Portland, but by all accounts the area now known as the Pearl was pretty sketchy 20 years ago, particularly at night. The Lloyd today has some of the same issues the Pearl did back then – a large number of people there during the day, and not many people there at night. As thousands of new residents move in—and with them restaurants, bars and cafes—that will change.

I can second this evolution of NW, what I called Chinatown when I was a kid and teen was where my mom and I went for lunch only, never a night spot. ‘The Pearl’ still sounds like DUMBO or some weird development name to me, but it is nothing like its former self. The gravel roads of NW were not safe.

Now, despite some of my misgivings about the actual pearls that were once Chinatown, The Pearl is one of the safest places in the city. We may tend to underestimate the importance of the effect residents have on a neighborhood. The number of people in a place is certainly not the only variable, but it is a big ingredient to making a place where other people want to go… especially at night. I don’t remember the Lloyd ever being one of these places. Good news.

Jane Jacobs.

We’ve seen similar effects in Chicago’s Loop. In recent decades, it was busy in daytime and mostly deserted at night. Pockets of highrise residential development and old office buildings being converted into new hotels has revitalized the area. Having people in a neighborhood at all hours makes a huge difference.

Having worked in the Lloyd district for the last 8 years it is really exciting to see these changes. But the mall needs to be torn down and turned into something more attractive to those willing to pay the crazy rents being asked by these new residential developments.

The more people who live in the district, the less abandoned it will be, and harder it will be for the thugs to get away with nonsense.

Actually I just got home from work at the old theater remodel. I doubt very much it’s demise was car prowlers, it is more likely that it was a very small and old theater, and most likely wasn’t big enough to get a get a decent ROI with modern updates (new projectors alone are roughly 500k each – (having just built a theater last year from ground up). Also, theaters by in large have been struggling the last few years as well.

It’ll soon be creative spaces – ie offices.

Though honestly if these new developments prove successful.I suspect the mall itself is only about a decade away from being torn down and turned into another high rise (that Multnomah side change implied in the article have been problematic throughout the bid phases and as far as I know has not been greenlighted yet). And having done work on many of the store remodels, it would probably be better to do so sooner than later, I’ve been in worse buildings (as far as construction/craftsmanship) from the era for sure, but the original builders definitely built it with the “eh – that’s good enough” attitude.

The mall’s new owners acquired the Lloyd 8 (in the mall) and Lloyd 10 (outside) theatres. It seemed clear that one should close, since they showed the same movies and 18 screens was way more than needed. But now both theatres will close, Lloyd 8 to become office space and Lloyd 10 to become an apartment complex.

That seems odd. With Lloyd 10 gone, wouldn’t Lloyd 8 immediately become significantly more profitable?

The result is that there are no multiscreen movie theatres in close in eastside Portland. Good for the handful of single screen theatres in the area. But it will mean a lot more trips across the river, just to see a movie.

From my understanding big-name theaters have distribution contracts that prevent nearby theaters from showing the same movies. It could be that the demise of these big theaters leads to a renaissance of more, smaller theaters on the eastside.

I wouldn’t mind seeing a few living room theaters, cinetopias and other similar small scale theaters pop up in its place.

Multnomah Co. library has thousands and thousands of free movies you can check out.

Books, too. But you know, a movie out is pretty fun also.

Yeah. True.

Or take a page from former Mayor Sam Adam’s play book…Go North!! and see a movie at Vancouver’s Regal City Center complex in the downtown…if you like ananomous chain theatres, chain food and “free” parking. Otherwise, my choice would be the Kiggins…

“The mall that Lloyd’s children built is still the biggest one in Portland, but malls are on the wane across the country. After Nordstrom’s began to signal that it was pulling out, the mall’s owners sold to a Texas-based company, Cypress Equities. It’s announced plans to redevelop part of Holladay Park, remodel the parking garage to create a direct street entrance for the first time, and open a row of street-facing shops along Multnomah.”

Been to any suburban shopping malls lately? They don’t seem to be on the wane – it’s just Lloyd Center.

It better be one heck of a renovation – at the moment, Lloyd Center is doing a fine job of looking like a rapidly dying shopping mall.

Mall 205 isn’t looking so great.

Mall 205 also isn’t in the suburbs.

Mall 205 is within the boundaries of the City of Portland, but it was located in unincorporated Multnomah County when it was built. The mall itself and the surrounding land use patterns are distinctly suburban.

Not that many years ago Lloyd Center remodelled and installed its glass ceiling above what was before an open plaza, wet and cold during winters and inclement weather. I remember the change. Immediately, the number of shoppers tripled and hasn’t decreased since.

They should demolish it and replace it with a string of Vancouver-style mixed use residential towers.

Yeah, all those suburban shopping malls are doing wonderful….

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/jun/19/-sp-death-of-the-american-shopping-mall

“people don’t tend to spend money on streets designed for speeding cars.”

Imagine that.

Speeding cars were replaced with a cycletrack, true, but they were also replaced with more on-street parking — a major reason for Multnomah’s redesign.

I was surprised that there was no mention in this article that this district was a Black neighborhood before urban renewal in the 1950s.

Fred:

I don’t think the Lloyd District proper ever was. The area west and northwest of the Lloyd District certainly was before the triple threat of the freeway, Memorial Coliseum, and Emmanuel expansion.

That’s a good point. The official city-defined “Lloyd District” boundaries include the Moda Center and Memorial Coliseum, the sites of majorly destructive urban renewal efforts.

However, Michael appears to be writing more about the Lloyd Center area east of Grand Avenue, which has a very different history based on un-development rather than re-development and displacement.

Despite sharing arbitrary neighborhood boundaries, the two areas have drastically different histories. The urban renewal story of NE Portland is an important one, but maybe belongs in a different series of articles.

I seem to recall that one of the motivations for “urban renewal” in what is now the Rose Quarter was so that white residents west of the river could travel to the Lloyd Center without having to pass through a black neighborhood.

Belatedly: I agree, great point. But yes, the Holladay’s Addition / Lloyd area discussed here was mostly east of the neighborhoods where a lot of black families lived from the 40s until being displaced by “urban renewal” projects in the 60s through 80s.

I could be wrong and I’ll gladly be open to hear otherwise, but before a large movement of southern Blacks to work in the WWII shipyards of Swan Island there were no black neighborhoods in Portland. Henry J Kaiser recruited work for his west coast ship yards by basically saying “Want to work in the shipyards? You do? Here’s a train ticket out west.” My understanding is that any Black population that existed here in PNW was *tiny* before WWII.

The big Kaiser yards were on the Columbia near Delta Park. The Black population prior to that was very small, centered on a small population of railroad workers and their families. It looks like at first in Old Town, and later in the Vancouver/Williams/Broadway area.

http://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/blacks_in_oregon/#.Va7IuaRVhBc

Yes, there too, but Swan Island as well (one of my favorite neighbors ever, Ann, she and her late husband Bill moved out here from South Dakota in the 40s to work the Swan Island shipyards. They lived in Kenton the entire time and for almost all that time in the same apartment as well. She had amazing stories about Kenton and Portland and life in general) I took a great class at PSU a few years back, it was a history of urban America and it had an awesomely heavy emphasis on Portland. The professor was Chet Orloff, he was or still may be the Director Emeritus of the Oregon Historical Society. Interesting guy, very interesting class.

Thanks for that link.

From Museum of the City:

http://www.museumofthecity.org/urban-renewal-and-the-lasting-impressions-on-portland/

“Years later Voters would approve the building of the Memorial Coliseum in 1956 which was the first of several projects to clear areas of “blight” in the Albina district displacing not just the Black homeowners and renters, but the businesses they used as well.”

There are a lot of great sources on this. My wish is for Emanuel and the City of Portland to return some of the property it acquired, and has yet to develop. What this would mean and how it would be done, I haven’t a clue. Here’s an OPB doc on the razing of Albina.

http://www.opb.org/television/programs/oregonexperience/segment/portland-civil-rights-lift-evry-voice/

And note that the OPB documentary draws on PSU Library Special Collections, especially the Avel Gordly Papers and the Rutherford Family Collection, as well (notes the proud librarian)!

One thing I’ve long recommended is demolishing the freeway stub connecting the Fremont Bridge to NE Kerby Avenue, bringing it to grade much more quickly and integrating it into the street network–and then connecting the hospital back to the neighborhood to the north.

Would likely free up some land for development as well.

Great article. Fascinating history. Positive outlook for this area. Thank you.

I have been working in this area for about a year. It’s changed a lot since then, but I’m still dismayed by the lack of safe bike infrastructure. It would be so nice if NE Multnomah was turned into a second “transit mall” that fully separates bus, bike and car, and if NE Holladay became bike / walk / train only.

How much change did you expect to see, in just a year?

And the occasional parking garage access on Holladay?

Good story Michael! As I recall Holladay made out very well in selling his stage coach network to Wells Fargo just before that mode sagged with the coming of the railroads. But Wells Fargo did OK as well!

Holladay was then involved in the pitched battles to see who would succeed in getting a rail line to California and garner all those federal land grants. In the end nobody got ’em or if they did, the US reclaimed them. They are now the “O&C Lands” managed by BLM.

Also, my 1918 Portland rail map shows the 15th Avenue streetcar coming off the Steel Bridge, then up Holladay, jogging north on Grand, then east on Multnomah to 15th and north to Prescott!…through the heart of the district!

When the shopping center opened in the early 60’s, it was definitely the cool place to hang out (just as it is today!) Wilson High, class of ’64.

If I had more than two thumbs, I would point them too, in an upward direction in support of this great article! Nicely done, Michael!

Paid for by Hassalo on Eighth? http://hassalooneighth.com/

appreciate the history.

Stellar piece of reporting, Michael! What an interesting read. As a NE Portland native (third generation, even!), I was familiar with the Lloyd Center shopping mall part of this history, but had never heard the non-development story.

I just started a novel set partly in Portland in 1910, so this is all doubly interesting to me!

what is the novel? 🙂

So far, about 14,000 words of groping towards a plot. 😀

Is bikeportland going for a pulitzer?

According to these cool old maps we should be pushing for a new bridge at 16th, not 7th! Actually, how about both? Ped/bike only, of course.

Love this: “a crime-ridden inner-city office park in the least interesting metropolis on the West Coast.”

Great article. I enjoyed the history lesson

Thanks, Michael. Great article. I work in the Lloyd District and have lived nearby, for 30 years. I like the changes that I see happening. And now, I have a much better historical perspective. Looking forward to Part III.

Great article, Michael. I love learning about the history of the city, especially the historical context that is still influencing the changes seen today.

“Some say they’ll benefit only the rich”: Boy, that was a good prediction!

Sorry for the late post but the Lloyd Towers, at least, have royally screwed up their new bike program already. I actually work in one of the Lloyd Towers and have been parking my bike for free in the 700 building’s bikeroom basement(FREE! w/ keycard access to boot).

As you may or may not have heard they constructed a fancy new “Go Lloyd” bikeroom(and made sure to close that pesky FREE one!) and an entire room with staff to assist. Showers, lockers, etc. with a $20 annual registration IF you are in the 700 building or IF you want to pay up. If you work in any other building you have a $15 monthly charge on top of that. If you want to use anything other than the racks, be ready to pay big annual fees up to $300+ dollars.

So if you don’t work in any Lloyd building you’d be looking at least $200 annual fees to park your bike alone.

Additionally I checked with the parking office in my Lloyd tower(across the street) and they indicate you are not to leave any locks overnight on the racks outside.

SO… you have to either ride with that hefty lock everyday to lock your bike up outside or pay up!

You might not have to be rich to benefit from bike services but everything about their bike program and policies says: 1) We are going to make it either financially or physically difficult for you to commute, 2) we are more interested in protecting our liability than encouraging you to commute by bike and 3) if you aren’t going to pay-up for our new bikeroom then good luck riding with your heavy lock every day.

I’m not sure if anyone else has mentioned this bogus bicycle program but I find it like a slap in the face from the Lloyd Towers. You want to commute? Pay up or we’ll make it more difficult for you.

Nice bike program Lloyd Towers. Real nice!

P.S. If you want any more information on this I’m happy to provide. Thanks for listening.

Thank you for this interesting history. RB Lloyd was my great grandfather and while there is indeed some family mythology about him, this article filled in some gaps. A few small corrections or clarifications: He was born in Missouri, not California; he had four daughters, not three; he went to college at what is now UC Berkeley, which is not SF (probably a distinction only a Californian would care about); and the family ranch and oil operations weren’t in LA, but Ventura County to the north (again, a distinction that may only matter to a Socal local…).