Portland-based urban planner and designer Nick Falbo’s latest project aims to expand the benefits of protected bike lanes — places where people can ride with physical separation from auto traffic — all the way to intersections. Falbo calls them “protected intersections” and he’s launched a website and new animated video to help spread the idea.

The problem with protected bike lane (a.k.a. cycle track) designs in America is that they disappear at intersections. The favorite treatment of U.S. planners has been to create “mixing zones” where people in cars and people on bikes share the lane just prior to the corner. This design creates a weak link in the bikeway right where it should be its strongest. In contrast, cycle tracks in Dutch (and other) cities have dedicated space for cycling all the way to the corner and then bike-specific signals to get riders through safely.

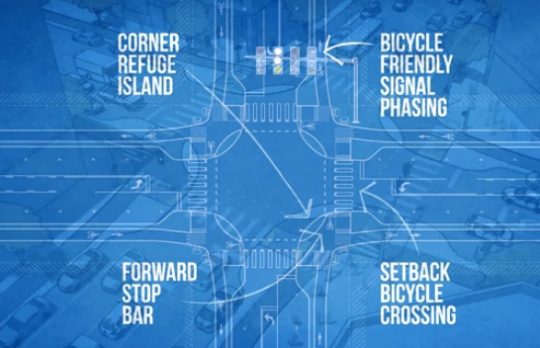

With his protected intersections for bicyclists, Falbo is trying to translate that Dutch design into an American context. As you can see in the image below, there are four key elements to the design: a corner refuge island, bicycle-friendly signal phasing, a forward stop bar, and a setback bicycle crossing.

In an email to the Active Right of Way list this morning, Falbo said, “I hope to hit a few conferences this year pitching the these elements to whoever will listen.”

While he’s obviously enthused about the benefits of this design and committed to moving this idea forward, Falbo acknowledges there are some major challenges to overcome like large truck movements, auto capacity impacts, and how to make the design work well for people who walk and/or use a mobility device.

Falbo intends to tackle these challenges and post updates on his design to ProtectedIntersection.com, which he hopes will, “develop into a clearinghouse for exploration, examples, images, references related to the Protected Intersection design concept.”

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Physical and temporal protection at intersections. Brilliant and clearly depicted. Three cheers for Nick Falbo! Seriously, this is great, thank you.

Now this is what I’m talking about. Copy the Dutch design. They already figured this stuff out years ago – no need for American cities to reinvent the wheel.

Here’s hoping this design actually gets implemented in Portland and other American cities.

Copy, at the intersection anyway. One thing I see in the Dutch videos is long blocks without driveways, not something we have in Portland.

Where are the dimensions?

http://www.aviewfromthecyclepath.com/2011/08/but-we-have-driveways.html How the Dutch deal with driveways.

Nice link to illustrate my point. Mostly long blocks, mostly in high density urban settings, and the locations that have parking on the street don’t have center turn lanes or a furnishing zone for trees, poles, hydrants, etc. Where’s the cycle track with driveways for each 50 ft home frontage, or with an intersection every 250 ft and a commercial driveway every midblock?

Many years ago I attended the University of Illinois where there were several bicycle facilities that consisted of two-way, separated paths adjacent to, but physically separated from the streets and sidewalks.

These facilities are not without problems. The separate bike facilities were nice where there were no intersecting driveways or streets, but where there were, big problems were evident. Bicyclists were in an unexpected location for turning motorists. I personally saw more than one collision between bicyclists and motorists and between motorist and motorist because of this. The facilities at the U of I did not feature separate signal phases for bicycle movements. The separate signal phase could alleviate this, but as Nick acknowledges a separate signal phase has significant impacts on motor vehicle capacity and potentially on pedestrians, as well. (Yeah, I know no one reading this cares about motor vehicle capacity, but some others in the community do, believe it or not.)

Don’t get me wrong; I think it would be great if we can develop an approach to transportation more like the Dutch, but before we can make such significant changes, I think bicyclists will need a much higher share of the transportation use than currently experienced. I think we’ll also need to demonstrate a higher compliance with existing laws if there’s going to be any likelihood of implementation.

Let the flames begin.

“bicyclists will need a much higher share of the transportation use than currently experienced.”

What i gather your saying is that before we can have the infrastructure we first need to see more people riding bikes more often.

Right?

Not going to happen with the current death-trap infrastructure that currently exists.

There needs to be better implementations that are safe enough to get the general masses to use bicycles on regular basis.

So, therefore, in order to increase ridership we need better infrastructure. But in order to get that infrastructure we need an increased ridership. See how this doesn’t work?

“…”bicyclists will need a much higher share of the transportation use than currently experienced.” …” J_R

What that means to me, is that a higher travel mode share of people biking would be the essential support likely required for such changes.

If the current, overall travel mode share of people using Portland’s street would support building some kind of intersection design such as Falbo is suggesting, that would be a step towards it happening.

The problem is Portland has pretty much maxed out the number of people they are going to get on the streets with the current infrastructure. Any more is going to require a total redesign of the environment similar to what is proposed, only pervasive. Everywhere in the city is going to have to be redone to get the next batch out of their cars and onto bikes.

Many of Portland’s central thoroughfares probably are maxed out during business hours. I’d say they some roads also are maxed out in suburbs of Washington County where I live.

I’ve yet to watch Falbo’s video due to this limitations of dial-up, but have read some about and seen photos of the the type of cycle track and intersection design used in the Netherlands. I’ve got to wait to see the video to have a better sense of it’s potential, but Falbo’s intersection idea may work for some congested intersections in Portland and elsewhere.

People have to feel the need for dramatic intersection redesigns, before they’ll support them. Out in Washington County, whose suburbs are growing with corresponding pressure on roads whose functionality is archaic in terms of meeting current, overwhelming motor vehicle use tendencies, the accommodation strategy is to widen roads, primarily to provide more lanes for motor vehicle travel rather than bike travel. Portland’s road network grid is different than that of Wash. Co, but I think the travel mode prioritization is likely much the same.

When you say: “…Any more is going to require a total redesign of the environment similar to what is proposed, only pervasive. Everywhere in the city is going to have to be redone…”, to me, that suggests the community design itself, in addition to the road and street infrastructure, likely will need to change before support for dramatically different road/street intersections will occur.

The community design that’s evolved in the last 20 years out in Washington County around 170th and Baseline, is very weird in some respects. Installation of light rail has prompted some development of multi-story multiple family dwellings nearby to the train stations with the idea residents might largely turn to rail for transportation, rather than private motor vehicles. From the get-go though, the roads surrounding these developments, have been, and continue to be designed primarily for an increase in motor vehicle capacity rather than bike travel.

Agree.

Believe it or not, some of us walk, bike, and drive, and are knowledgable enough to know that smart street design improves the experience for every mode of transportation. And it doesn’t do any good to stereotype this community like that.

YES!! A million likes for this intersection design. One question: what about drivers turning right on red? I assume there would be a no right on red sign, but some drivers interpret that as a suggestion, rather than a definite. Maybe the tight turning radius would slow them down enough?

Tight turning radius, plus they’ll nearly be head on to the bike crossing once they’re there. Removes some of the problems associated with having people watch their right mirrors before right on red.

a safer design but also one that creates choke points and may therefore not be appropriate when bike traffic is heavy. i suspect that on a busy route in portland many cyclists would simply cycle around these islands if they were to become congested (i witnessed this behavior in amsterdam, btw). i think the best solution for busier bike routes is dedicated bike signalling.

Hard to retrofit to downtown also.

I don’t see anything that keeps walking folks (of all ages including very young, plus their dogs) from doing their thing all over the bike lanes. Seems like whenever walking and biking lanes are neighbors, they get all mixed up. Need only check out the SW Moody cycle track and the Moody crossing at the Tram to see that in action. Volume is light enough on Moody to limit consternation, but in a downtown setting like this appears to be? Yikes.

This points to substandard sidewalk widths and commercial tenants illegally using public sidewalks as commercial sales floor. I’ve always thought the best way to stop businesses from using narrow sidewalks as their business space would be to assess taxes on its use.

Have you been on Moody? That isn’t happening there at all. There are generous sidewalks and no businesses (yet) to speak of. There is just a ton of (non-car) space and pedestrians tend to go where ever they want.

I agree! I also don’t see very good protection for peds from cyclists! One only needs to attempt to walk on the Esplanade or Springwater to encounter a problem with a ragin’, impatient cyclist.

If cycle tracks are already a challenge to sweep and plow, I’m less than gung ho about putting four awkwardly shaped debris pockets at their intersections.

J_R “nice where there were no intersecting driveways or streets, but where there were, big problems were evident.”

This couldn’t be more obvious. Cars waiting in the bike crossing at every. single. intersection.

The Simultaneous Green phase resembles a square shaped roundabout for bikes only.

If you let this run for 15-30 seconds at a time in a high traffic intersection AND bicycle riders treated it like a roundabout (entering traffic yields to traffic in the circle/square loop) it might go a long way towards demonstrating to automobile drivers that roundabout intersections work better too.

Yes! And a thousand cheers to Nick Falbo for doing this!

While communities in the US have been making strides towards more protected infrastructure the lack of protection at intersections is *the* 800-lb. gorilla in the…intersection to conquer.

Thankfully, the best practices related to these have already been established through trial and error done on the part of the Dutch for decades. Sure, some local US-specific mods may need to be made, but these kinds of designs absolutely need to be implemented here.

Ok, so earnest question…how do we get these ASAP?

1) First of all, are there any communities in the US whose environment (political/planning/code-wise) would allow these today?

All we need is one “trailblazer” to get these going in real life to show other places it is possible here and allow people to experience them in real life. The less exotic/experimental/radical these things seem to engineers/city planners/city councilmembers/the public at large the better. Some bicyclists unfamiliar with them in person even sometimes have some understandable concerns about their design on paper but I suspect most of these fears will melt away for most of those people upon actually experiencing well-designed infrastructure treatments like these.

2) If no community is currently willing/able to make these street-ready now, then second-best is a strategy that involves demoing these things.

If so, how we do we get those off the ground? I know at least personally I’d love to volunteer my time and efforts into something like this but am unsure what the best channels are to do so.

This is very well thought out, but it might be difficult to implement, especially on Portland’s tight streets. In retrofit applications, the tight curb extensions and tight radii are great for bikes, but not so great for freight trucks. In new construction, property and right of way lines might be a problem.

The solution is to switch to smaller trucks. Full-size 55 foot trucks shouldn’t be allowed in dense urban environments anyway, because they pose a safety threat to all road users.

Agreed. The freight community needs access and is a consideration in planning out complete streets, though. The Burnside-Couch couplet would be a good example of the backlash that can result when they aren’t somehow accommodated.

Giving “access” to the freight “community” is one of the main reasons 13 people a year die riding bicycles in London UK, where nearly half are killed by HGV of some kind, highway vehicles that are completely unsuited for use in a city. It’s like trying to deliver goods to the door by freight train. When the freight “community” decides to use city vehicles to deliver in a city then they get a seat at the table. Vehicles that you can’t see what’s in front of your vehicle for half the width of a normal intersection should not be allowed to be used in a crowded urban environment. Vehicles that you can’t see what is beside you in an intersection should not be allowed in an urban environment. Put vehicles that the drivers can see what is around them in an intersection and then consideration will be given to freight.

Search ‘Safe System, OECD/ITF, 2008’ for more info. Chapter 5 is pretty good. We currently operate under the idea of mobility ahead of access and safety, when safety should always come first. Non-motorized right of way consumers need to get more organized to push back against the motorised consumer lobbies. Anyone for an Oregon constitutional amendment that requires ‘All jurisdictions with design and operational control of a public right of way shall place the access and safety of all users of such rights of way ahead of the mobility of any single mode where such rights of way are shared by more than one mode”?

Compliance problems would likely sabotage the safety aspects of this design, as good as it may be. The two big ones: “No right turn on red”, and “Stop here on red”.

Rights on red are really only dangerous to cyclists/peds in two instances:

1. Driver staring left turns right without looking just as the through signal turns green and the crosswalk fills with bikes/peds.

2. Driver turns right on red while a separate bike signal is green for through bicyclists.

Both of these problems should be eliminated by posting protected intersections “No right turn on red”, but there are plenty of drivers who will never give up their “right” to make turns on red, regardless of signage.

As Oliver mentions above, the other issue would be drivers failing to stop before the crosswalk/bike crossing. Usually, this is due to anticipation of making a right on red, causing drivers to cruise right through the crosswalk before stopping to check cross traffic, but some drivers just don’t care about blocking crosswalks.

One other issue crops up in my mind as well–regarding blind spots. I’ve noticed that an increasing number of drivers have a blind spot that is right in the center of their windshields. Modern cars seem to come with some sort of mobile device that blocks the view out the front of the vehicle, so that even if a crossing cyclist/pedestrian were directly in front of such a vehicle, the driver still wouldn’t see them.

Regarding your advancing auto past the stop bar comment. The Dutch are working to remove lights and instead decouple bike/auto routes (making the cars go around) but also replacing lights with roundabouts, this can happen in many communities right now. Anyway a key feature for intersections with traffic lights is the placement of the lights. In the US we mandate that lights must be placed on the opposite corner of the intersection and typically include an overhead component as well. Many Dutch intersections place the traffic light next to the stop bar and if overhead do not provide a light on the other side of the intersection. This means that if you advance past the stop bar you can’t see if the light is red or green and basically forces most folks to stop in the proper location (it is very unnerving to be sitting out in the middle unable to see the light, on a bike or in a car). We need to reevaluate stop light placement at intersections, especially when dealing with proper separation as this can contribute to right turning issues and intersection blocking if not dealt with correctly. Here is a good example from Assen: http://goo.gl/maps/cBnnQ

note the placement of the lights in relation to the stop bar. The overhead lights may be a bit closer to the actual corner but still usually before the bike lane crossing. The Dutch do not do things piecemeal they look at the whole picture, auto access, bike, ped, traffic light position, street light, sight lines etc. We must make sure we do so as well when requesting better infrastructure, in this case we might be bumping heads with official design guides again though…

It’s kind of amusing that your google maps link is adjacent to a warren of commercial-residential streets with advisory bike lanes and/or no bike lane. If PBOT tried to propose advisory bike lanes in the Pearl or south waterfront I’m sure there would be lots of complaints about “paint on the road” not being progress.

I don’t see any warren of streets without cycle tracks or with “advisory bike lanes” near that site. Unless you are talking about streets that have speed limits of 18.5 mph or below, and low traffic volumes. Is that what you mean? Fortunately the Dutch are the world experts in integrating bikes, so they know that you don’t need protected/separated infrastructure at low speeds with low volumes.

The frontal blind spot isn’t just due to mobile devices. Newer cars have huge blind spots in front. This is due to larger mirrors, and wider A-pillars (between the windshield and the side doors) to house airbags. My newer Hyundai has huge blind spots in front, large enough to hide an adult pedestrian standing right off my left front corner. And on the right side, folding down the larger-than-they-used-to-be visor means I really only have a small, interrupted slot to look out of in that direction.

So now when I come to a stop in a place where there may be pedestrians I’ve now learned to move my head left and right to check around the blind spots before I go again. The scary thing is that most drivers don’t seem to have noticed the change, and haven’t learned new habits to deal with their new blind spots.

Just to be clear, this is not specific to my car either: it was true of most of the other cars we looked at. For instance, while my wife was test driving a Honda Fit, she almost plowed us into an 18 wheeler coming across our path. Even though it was right in front of her she couldn’t see it.

Absolutely. Forbidden right-on-red should be standard with these designs, but thankfully the design also allows for checks on drivers disobeying this due to the fact that:

1) bikes’ waiting lines are physically and visually so much further ahead of cars so both bike and car can see each other.

2) the turning radius is tighter

3) the setback crossing point for bikes means there’s a full car length between turning cars and bikes, as demonstrated in the video.

These all go a long way towards protecting people on bikes even if a driver flouts the right-on-red rule. But also, prominent signage and enforcement of no-right-on-red especially in the first weeks and months of these things going live should be strict. There’s no excuse–it’s not like no-right-on-red intersections are a foreign concept to American drivers so they should already be familiar with that anyway.

Yes, those sound like very substandard implementations and that’s unfortunate.

But of course that’s just further proof that it’s not protected infra that’s the inherent problem, it’s *poorly designed* protected infra that’s the problem. If designed in the way Nick’s video demonstrates 99% of those problems would be fixed 99% of the time.

Yes, those are valid concerns for urban planners/engineers planning these things out, but they’re not insurmountable problems. Smart signalized timing and even features like bike sensors + beg buttons in the refuge area can all go a big way towards addressing this.

This is of course without mentioning the modeshare-increasing power of this kind of top-notch infrastructure. As some of those cars become bikes some of the time, car traffic proportionately diminishes as an issue with each point in bike modeshare gain.

Some also had similar fears about protected cycletracks, but now that those have been around for several years in the US now the data are starting to come in. For example studies on LOS (level-of-service or car throughput) in Long Beach, which has been really expanding its cycletrack network, have found that LOS remains unchanged even as bike modeshare and bike lawfulness/compliance have shot up in areas with protected infrastructure. I’d be willing to bet that with good design at intersections similar results would be seen.

But that’s really the chicken-and-the-egg issue here. Modeshare is to a huge degree so low now precisely *because* current infrastructure is so bad. There is no one silver bullet to increase modeshare and as always a multi-pronged approach should be taken, but protected infrastructure (including at intersections) is a huge deal especially on busier streets.

Also, compliance goes up with better infrastructure. To prove that it’s not just some hivemind cultural Dutch thing, places in the US as diverse as Long Beach to New York to Chicago have noticed compliance with bike laws goes up with better protected infrastructure. Current rule-breaking is not because most people on bikes *want* to do things like ride on sidewalks and the like—those are mere coping strategies for dealing with the current status quo of terrible infrastructure.

As I’ve said before, if you build good infrastructure and then someone still flouts it, *then* we can absolutely throw the book at them as there’s no excuse.

Excellent work communicating these ideas, per usual, Nick. This is getting towards the types of bike infrastructure that even committed automobile users should be able to get behind simply because it eliminates so many conflict points and opportunities for “unpredictable” vehicle (both bike and car) movement. A few questions:

1) There is a lot of concrete real estate dedicated to the curb extension, wedge island, etc. Do you think this space is usable as stormwater catchment, plantings, benches, and the like? Or will visibility be too impinged? This is likely a case-by-case question but I’ve found in my projects much more funding success when we’re able to kill two or more birds with the same stone (not to relive Portland’s unfortunate “sewer fees for bike lanes” PR nightmare from a few years back….)

2) Do the Dutch have solutions for reducing bike/ped conflicts at these intersections? It looks like peds are supposed to wait back inside the bike lane channel, but as this functions like a general curb extension for people on foot, I can foresee people wanting to advance as far as possible into the extension before the crossing signal turns. This will be bot a design and behavior issue.

Anyway, nice work. I look forward to following the evolving discussion.

Ben,

based on the tight radius of the intersection, I think the wedge would have to be “roll-over” to accommodate large trucks and buses

The solution is to switch to smaller trucks. Full-size 55 foot trucks should not be allowed in dense urban environments anyway, because they pose a safety threat to all road users.

I agree, but how does that happen?

Road authorities can restrict vehicles in their own jurisdictions. State controlled roads and NHS roads have to meet the state and federal guidelines. Portland may be able to legislate truck size on it’s roads, maybe as part of the upcoming transportation system plan update. Justified by cost to accomodate, or safety, maybe, but not emissions. LA used to have time of entry restrictions to downtown – no trucks 6 AM to 6 PM.

Also two trucks delivering to two locations are likely to use more fuel, pollute more (cost more) than one delivering to two locations.

We heard you the first time.

Ban large trucks above a certain length from the city center. Delivery companies will have to adapt. This works in many Eurpoean cities, where large trucks deliver to places outside the city center, then transfer to smaller trucks.

This is also consistent with Vision Zero, because it reduces the risk associated with allowing large vehicles in the dense downtown area.

Agreed, we need to think about banning 53′ trailers from urban areas. At least once a week I see a too-big truck trying to maneuver into a tight space somewhere in central Portland, usually blocking traffic and causing a mess.

Most of these are not long-distance trucks anyway, but have come in from distribution centers on the edge of town. So the DCs just need to send smaller trucks on some of their runs, instead of blindly sticking to the 53′ mentality.

That’s definitely a valid concern and will probably inevitably be an issue to some degree with novel designs, but I think as sheer numbers of bikes increase on these pedestrians will get used to the concept of these as exclusive bikeways because they’ll have to. If everyone’s always ringing their bell at you or yelling at you for being in the cycletrack most people will eventually get it, especially as they become more commonplace.

Of course maybe one way to further reinforce the point is to include frequent bike-symbol and ped-symbol stenciling/paint in the appropriate places especially in the first implementations of these.

Once locals get the hang of them I actually think the only remaining issue over time ends up being tourists unfamiliar with these designs. In Amsterdam the only place these were really a problem were in areas immediately between Centraal Station and the most prominent tourist hotels across a busy arterial. There was always a constant stream of tourists flooding out of the station to the hotels with luggage who’d cross the arterial and think they were safe in the refuge island or mid-block cycletrack only to find within 15 seconds some fast-approaching bicyclist dinging their bell and glaring at them. And then another. And another every 10-15 seconds thereafter. But as someone who biked through that area often I still don’t think even that was all that bad. People catch on quick. Bells, glares and even yelling HEY go a long way when absolutely necessary 🙂

Bingo. It’s the cyclists themselves that prevent this from being an issue. I’ve heard so many people complain about the “crazy cyclists” in Amsterdam. In reality, it is their fault, as they wandered into the cycletrack. It’s just something that will have to be dealt with for a while.

Of course this kind of treatment won’t work for every intersection, but just for a little spatial perspective and comparison the average Portland street in pretty much any area of town (even downtown) is quite a bit wider and more spacious than the average Dutch road/intersection. Yet they seem to have had few problems implementing these everywhere. Meanwhile Portland still finds plenty of room to do road diets.

The reality is that though these designs may look like they take up more room, they actually don’t necessarily need to take up any more room than a conventional bike lane. It’s just that instead of putting the curb to the right of the bike lane it goes to the left of it and the refuge islands are built outside of the turning radius cars *should* be observing anyway but usually don’t in practice because what would be perfect spots for refuge islands today are currently just intersection asphalt.

The solution is to switch to smaller trucks. Full-size 55′ trucks should not be allowed in dense urban environments anyway, because they pose a safety threat to all road users.

That is one of many solutions. It’s a good one, but it won’t help prevent the conflicts that occur between cyclists/pedestrians and all of the other vehicles.

I’m not exactly sure what you mean by not seeing protections for peds from cyclists in this design. In the type of design Nick showed in his demo, peds and bikes are indeed fully separated.

Springwater and the Esplanade are multi-use paths (bikes+peds officially supposed to use the same surface) whereas these designs are the opposite of MUP.

Gezellig,

the part that concerns me is the part where are bikes are supposed to stop behind the crosswalk then proceed across. Based on my experience with Portland’s cyclists 9and I am one), they can be can quite impatient, even hostile, to peds. I could see bikes staking up in the crosswalk, or cruising through it and having conflicts with peds.

There are definitely parts of the Netherlands with short blocks and many driveways, too. The problem is relatively easily addressed–here’s an example:

http://youtu.be/6imqI8VfwNo

In my experience living in the Netherlands that more suburban-style spatial development (low density, frequent driveways, etc.) that you see in the Dutch vid above is a lot more common than many might think. After all not everyone lives in the medieval center of Amsterdam or Utrecht, of course, so they’ve naturally had to find solutions to a great many of the same design challenges like driveways that face many American communities.

I completely understand how to achieve the design, it’s the paradigm shift that will be needed to achieve it, particularly the added space required, that needs to be overcome.

Do the math: 2 travel lanes is 20 ft (few trucks or buses), two parking lanes is 16 feet; two bike lanes is at least 12 feet; two sidewalks is another 12 feet; which totals 60 feet, a common right of way width in Portland, but provides no space for trees, poles (power, light, cable), or fire hydrants. And every swale will take at least one parking space away.

two travel lanes (20 ft) a left turn lane (10 ft) and two parking lanes (16 ft) is 46 ft curb to curb. Most 2-lane streets in Portland are 36 ft curb to curb. Then to auto space add a buffer on both sides (3′ x 2 or 4′ x 2) a bike lane on both sides (6′ x 2) furnishing zone for trees and poles (3′ x 2 or 4′ x 2) and sidewalks ( 6′ x 2 to 12′ x 2) and we’re talking about a lot of public right of way, (46+6+12+6+12) 82 feet minimum. Combining the buffer and furnishing zone only gets back 6 feet, so 76 ft is the minimum. Who can afford 76-ft wide rights of way (most are 50-60 feet)?

Better to change the parking lane into protected bike space.

Exactly. It’s the sheer increase in modeshare that further and continuously reinforces the fact that cycletracks aren’t for pedestrians.

If every 15 seconds someone’s whizzing by and yelling to get back on the sidewalk, you’ll probably get the hang of it. And if some pedestrian somewhere someday steps on a cycletrack where no bike happens to be around? Well, out of all problems I wouldn’t worry too much about that one.

Yeah, re: “crazy cyclists,” people on bikes are actually in general very mild-mannered in the Netherlands. There’s a certain peace, freedom…even joie de vivre in being on a bike in a safe space that will get you to your destination in a predictable, safe and low-stress fashion the entire way.

However, if you step into the cycletrack you will get some understandable glares and bells–because it *is* your fault!

People will figure it out, though. There’s always a learning curve for some people with new stuff, but I really don’t think that’s a reason *not* to build better protected infrastructure.

you paint a very idealized picture of cycling in the netherlands. dutch cyclists are not only justifiably rude to clueless peds but are also far more likely to engage in scofflaw behavior that their neighbors to the north. during bike rush hour in amsterdam it’s not uncommon to see cyclists jumping signals and spilling into auto space at intersections. and i should note that i’m a huge fan of this type of rebellious “taming the bull behavior” by cyclists and peds (e.g. jaywalking).

You’re not gonna hear any complaints from me about turning a parking lane into a bike lane! 🙂

I think my point is just that if there already is room for a conventional bike lane (which also sometimes necessitates parking removal especially since the newer conventional lanes Portland and some other places have been building are paint-buffered which require even more space) there’s probably also room for this.

Nick’s video just shows a better way to do intersections with roads that already have room for bike infrastructure. (And if they don’t currently, they might be getting a road diet anyway…I think the point is we might as well favor protected infrastructure as a part of road diets as opposed to paint-buffering and conventional intersection treatments everywhere).

No disagreement, but it’s part of a larger conversation that needs to take place. We currently put mobility ahead of safety in most of the US, including Portland. For a city to continue to grow and stay healthy, safety for all needs to come first ahead of better mobility for some and even convenience.

Your suspicions are unfounded in practice. There is vast evidence that this design works — look at the Netherlands where this intersection design is everywhere, and the crash rate is far lower than the US.

Adam-

I’ve heard that this intersection design is standard practice in the Netherlands, but I haven’t actually seen one in reality. Can you (or anyone reading this) post a location that I can see via Google Maps? I have the CROW manual and this treatment doesn’t seem to be a standard either. I’m not being confrontational, I’m just trying to see what one of these intersections look like in reality rather than graphics. Thanks.

https://goo.gl/maps/OXm7Z

Is this helpful?

https://www.google.com/maps/@52.99899,6.566088,3a,75y,273.27h,64.81t/data=!3m4!1e1!3m2!1sckX9AN46HLMLtQRQegeD2g!2e0

Or this?

http://bicycledutch.wordpress.com/2011/04/07/state-of-the-art-bikeway-design-or-is-it/

The idea that one infrastructure solution is appropriate or better everywhere is dogmatic.

It looks like this design almost mandates that people on bikes make a Copenhagen Left to turn left.

I really hope that PBOT is willing to give this a try on a few continuous blocks somewhere.

Willing yes. A variation was considered for Madison at 3rd. Space is an issue. Portland has already done a couple of ‘truck corners’, but these islands permit long loads to ride over the corner islands and are intended to keep typical traffic on the outside radius: SE Clay at 11th; N St Louis at Ivanhoe are the two current locations.

I guess I’m still just trying to understand and visualize your concern–regardless of whenever a person on a bike proceeds through the intersection (whether early or not) they won’t be endangering pedestrians at least because in this design bikes and pedestrians don’t ever share the same crossing space through the intersection. Just as the cycletrack is separate from the sidewalk, they both have separate dedicated widths when it comes to the crossway.

In Nick’s video the pedestrian crosswalk is the wider, zebra-striped crosswalk and the cycletrack crossway is the narrower one.

Not only are the spaces separated, there wouldn’t even be much incentive for bikes to intentionally veer over into the pedestrian zebra stripes because on a bike it’d be out of your way to the right. As a bike crossing that type of intersection your goal is to go as straight ahead as possible to either 1) continue straight ahead for the next block or 2) turn left once crossing to the next refuge island.

The teardrop refuge island also creates an area to the left of the bike stopline, giving every incentive for bikes to queue up there as opposed to in pedestrian territory.

I’m not an urban planner/civil engineer but as someone who simply lived in the Netherlands (and both walked and biked all the time) I can say these things do work beautifully 99.99% of the time whether you’re a ped or on a bike. So whatever spatial specs/light timing/etc. those people have figured out it’s largely working.

Btw, as for impatient attitudes and non-compliance, well-designed infrastructure goes a long way towards diminishing these problems. When it’s clear that everyone has their own dedicated space it’s only natural for most people to comply without even thinking about it because the built environment encourages it. I guess there’s more than just one reason protected infrastructure is sometimes called “low-stress.” 🙂

Except that unlike lefts in Copenhagen you’re protected by the refuge island while you’re waiting instead of out in the street so it’s much safer.

Yes, hopefully they try this out!

Well it’s just my experience but it is a picture painted from having lived in central Amsterdam, worked in a medium-sized town about 50km away and visited many parts of the country.

Both as someone who biked and walked every day I didn’t personally find scofflaw behavior to be all that common or noticeable. Sure, there are always going to be a few bad apples, and the more people are doing something (like biking) the more actual numbers of violations you’ll find but percentage-wise I’m sure their rates of noncompliance are much lower than those in most American communities with much more Wild-West infrastructure. For every signal jumped in the Netherlands you’ll probably have another 100-200 or more who approach the intersection and wait.

The biggest problem in Amsterdam are the motorcycles that use the bike lanes.

Where you see a large sneckdown, start imagining treatments like these!

I am not convinced that this sort of complicated design is necessary or feasible or affordable in Portland. I also confess to a fear that as more elaborate separated cycle infrastructure is installed, the expectation will mount that cyclists must ride there and “stay off the road!”. I ride all over Portland, on roads both with and without bike infrastructure, and I don’t want to be segregated off of “my” roads.

THAT BEING ADMITTED . . . I would very much like one largish, two way, well traveled, accident prone Portland street to get this treatment, with seven or ten consecutive intersections of this design, as a real world experiment. Let’s spend $5 million (? more ?) and see how well it works.

By the way, is there a version of this design for one-way streets?

I communicate with some people from the Netherlands in making my blog, and their experience with the infrastructure is they can get anywhere they would need to use a car to get to without using a car and it’s much nicer on a bike, so why use the roads? Each mode of travel (foot, bike, and motor vehicle) has infrastructure designed to best accommodate it in the environment with minimal conflict with other modes. Even driving is more pleasant there than here.

Agreed!

I also totally disagree with the Dutch policy of allowing mopeds on cycletracks.

There’s actually a vigorous ongoing debate in the Netherlands about whether or not they should continue to be allowed. As things currently stand, Dutch road law distinguishes between several kinds of motorized cycles and pathways:

–> if you have one of those small (under 25km/hr max capacity) mopeds/scooters you’re actually *required* to use cycletracks signed as a Mandatory Cyclepath.

–> If it’s signed as an Optional Cyclepath those small mopeds/scooters can only use the cycletrack if they have an electric motor.

–> Signed Cycle+Moped Path: mopeds of any speed and engine capacity must use these cyclepaths.

It’s all kind of crazy, and can occasionally be really unnerving as a bicyclist.

Thankfully this is one problem a place like Portland won’t have as the rules are totally different and there aren’t distinctions between Mandatory and Optional and Moped+Cyclepaths anyway. Though I do wonder how things will evolve in the eyes of the law if e-bikes ever catch on in a big way, but that’s probably a whole ‘nother story.

But as a pedestrian you probably naturally abide by the fact that you’re not always given free rein to be in just any part of any roadway at any time. As a pedestrian on most streets you’re “segregated” onto a different channel (sidewalks) suited for walking.

This just carries that channel concept over into biking.

I wonder, does your concern about being on a different channel of the road (like a cyclepath) have to do with fearing being slowed down especially for left turns? In my experience with well designed intersections (like those in Nick’s video) it’s almost never an issue. Smart signalized timing can effectively turn these types of intersections into a squarish roundabout for bikes so you’re not waiting long or even at all to turn left. And of course on a bike you get a freebie anytime right turn in an intersection where vehicles (and those bikes behaving vehicularly) are required to stop at red.

I find that many high-stress vehicular lefts at least seem to take longer than these protected lefts I was used to in the Netherlands because you can usually just sail through those in one shot.

As a cyclist who is comfortable riding with and in traffic, I do not want to be segregated to 4 foot wide cycle tracks clogged with the “interested and timid” or whatever the term is. I also do not want drivers to be relieved of their duty to drive carefully and respectfully around cyclists, by the excuse that bikes don’t belong in the road. I am dismayed by the suggestion that building cycle paths or bike lanes mean cyclists must stay off the rest of the road. If that is where we are heading, I’ll oppose funding or building any such cycle infrastructure.

I would like to see Portland become a city where traffic moves more slowly, drivers and cyclists share the road, and an average person with average cycling abilities can safely and comfortably ride most of the city’s streets in the traffic lanes, and can safely ride the remaining streets in cycle tracks (excluding freeways and a few true arterials.) Put another way, I vote for integration, not segregation.

Thus, while I’d like to see protected cycle tracks and intersections tested and, if successful, used in the locations of highest need, I do not want Portland to be covered with the things. Which we can’t afford to do anyway, not in anyone’s wildest dreams.

Whether or not you want you feel comfortable sharing the road with cars is irrelevant here. Protected cycle tracks have been shown to improve safety for all and encourage droves of new people to ride in them. Your personal desires don’t outweigh safety. When bike and car traffic is mixing in the same space, people get hurt.

Adam can you provide proof of what you say in the US?

Why does the country matter? People are people everywhere, and designs work because they change people’s behavior.

Here is a study conducted by Harvard where they tested bicyclist injury rates on cycle tracks versus in the street in Montreal. Culturally, Canada is not much different than the US, so you should be able to apply the findings here. http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/early/2011/02/02/ip.2010.028696.full.pdf?sid=a2ed422a-9dbe-409a-b762-40e0ffbcedc6

The study’s ultimate conclusion was: “these data suggest that the injury risk of bicycling on cycle tracks is less than bicycling in streets. The construction of cycle tracks should not be discouraged”.

“designs work because they change people’s behavior.”

True enough. You put a bird in a cage and it won’t fly anymore.

I would like to see a study where they compared “cycle tracks” to streets with bike lanes. I didn’t read much further when I saw that the “methods” of the linked study included comparing cycle tracks to streets “without bicycle facilities”. I might concede that in many cases something is better than nothing, but I might debate which something is better than something else.

Force me to ride at 7 mph behind all the 8 and 80-year-olds in the cycle track while cars whiz by at 20 – 25 (a speed I could go given the right terrain…)?

Advantage: cars.

Force me to always stop prior to making any left turn (because I have to cross two streets to do it) while cars may just turn when it is clear or when their single left turn signal is green?

Advantage: cars.

Give drivers a wide boulevard–perhaps a one-way with three or more lanes, while I’m stuck in a narrow gauntlet with no way around obstacles that might be present in my single narrow channel?

Advantage: cars.

Until a facility grants me on my bike some advantage over driving a car (and “not dying” doesn’t count, I’ve been doing that without cycle tracks for years), I’ll always prefer a plain old bike lane or nothing at all.

I don’t ride my bike because I have all day to get places and I like to go slow…

comparisons of bike lanes with cycletracks were conducted in denmark and germany. these studies are rarely cited by proponents of cycletracks for obvious reasons.

“…Force me to ride at 7 mph behind all the 8 and 80-year-olds in the cycle track while cars whiz by at 20 – 25 (a speed I could go given the right terrain…)? …” El Biciclero

If and when some city within the Portland Metro area comes to decide upon and proceed with developing a basic cycle track system, quite possible, is that people traveling by bike that are capable and interested in maintaining a speed exceeding that of cycle track users, that’s fairly compatible with that of main lane users…will still be entitled to bike on the main lanes of the road.

More info from countries with cycle tracks, about road use regulations related to use of cycle tracks, would help understanding of what regulations may come to be associated with cycle tracks, possibly to be built here.

I’ve heard that where they exist, use of cycle tracks is encouraged, but that when traveling by bike, use of main lanes where cycle tracks exist, isn’t necessarily mandatory; that if a person can more or less maintain main travel lane speeds and not unduly hold up traffic there, they can ride the main lanes if they need do so.

I know you have a more liberal interpretation of this law than most, but if you read the text of ORS 814.420 carefully, you will see that all cyclists in Oregon will be legally constrained to use any infrastructure that has been “deemed safe for use at reasonable speeds” unless they take an entirely different route along which no such infrastructure exists.

I would not, for instance, be able to claim that I often encounter extremely slow riders or loiterers in the cycle track, therefore I don’t use it because it is safer to use the street. Potential hazards or dangerous conditions are not mentioned in the statute, and temporarily riding outside a cycle track for the purposes of passing or avoiding actual hazards (which is the intended application of all the exceptions listed in 814.420–temporarily leaving a bike lane in the presence of an immediate, observable obstacle/hazard) is not possible due to the physical separation of the cycle track from the rest of the roadway.

I’m sorry but the country does matter. You can spout about European countries all you want, but the bottom line is they aren’t the US, they don’t have our history with automobiles. They don’t have our massively spread out population. They don’t have the same sources of funding.

Simply telling me something works in the Netherlands so it obviously has to work here is just never a convincing argument.

“When bike and car traffic is mixing in the same space, people get hurt.”

Also, when cars mix with other cars in the same space, people get hurt. When bikes mix with manhole covers and train tracks, people get hurt. When bikes mix with potholes, people get hurt. When pedestrians mix with cars in a crosswalk, people get hurt. When bike traffic mixes with pedestrian traffic, people get hurt.

In general, when everyone isn’t paying attention, people get hurt, regardless of what is mixing with what.

There needs to be clear visual separation of some type so that it’s obvious what to do where.

Two examples in Vancouver, BC. One is Carrall Street. The cycle track and the sidewalk are at the same height. People walk on the cycle part all the time quite unawares.

The other is Hornby St. The sidewalk is higher with a curb separating it from the cycle track. At some spots, usually at driveways the cycle track rises to the same level as the sidewalk. There are markings to make it obvious that there’s a crossing there. All it takes is a polite little bit of bell dinging for people to look up and move to the side.

But the first few weeks when the Hornby cycle track went in, it didn’t work so well but then people learned and it’s all good now.

i’ve ridden hornby and dunsmuir multiple times and i found them to be unnervingly narrow 2 lane facilities. i can’t imagine the 8/80 crowd being comfortable being passed by a cyclist going 25-30 kph. they also have terrible sight lines. imo, a couplet of buffered bike lanes or one way cycle tracks without barriers/parked cars would have been a safer option.

This sort of thing is done to a certain extent already in most cities. Large trucks bring goods to the warehouses and then smaller ones bring them to the stores. All it would take is to have more of that. Those dispatching the trucks will know the city and what size truck could go where.

Nice! Yeah, I think most people catch on and get the hang of this kind of stuff.

That’s a great idea to have friendly flaggers guide people through the process in the beginning. They could reinforce car signals for any confused drivers while also being able to answer pedestrians’ and people on bikes’ questions right there. Cool!

That’s great that you can do that right now, but (making some broad assumptions here about your present age) what about when you’re 80? Would you have been able to do what you currently do when you were 8?

What if you became disabled and used a motorized wheelchair (those are allowed on bike lanes as per Oregon law) and found–as many do–that even “good” sidewalks are often less than ideal for getting around quickly and easily so it’s either that or exposing yourself to the dangers of the main road and/or conventional bike path?

The thing we need to remember is that these types of designs benefit so many more people than conventional infrastructure which mostly only serves those of us who are healthy/young/confident enough to do these types of things and have decided specifically to do so.

In practice that’s almost never a problem.

Plus, let’s face it–Portland is not a particularly dense city. So even if bike modeshare increases there’s a natural upper limit to just how many bikes are going to be out there at any given point.

Look at a typical ride through the center of Rotterdam. It’s a city with:

–> about the same population as Portland (both around 600k within their actual borders and 2.9mil in their greater metro areas)

–> much greater average density (about 3000 people per square kilometer as opposed to Portland’s 1700)

–> much higher modeshare (in fact, at about 25% its bike modeshare is the goal Portland has set for itself)

–> a major river crossing through the middle of the city (just like Portland) with many bridges spanning its width, all potential “bottlenecks” for all those bicyclists.

Rotterdam is also uncharacteristically spatially “American” in many ways with wide avenues, skyscrapers downtown, etc. Yet despite all this look at what getting around by bike in Rotterdam typically looks like:

http://youtu.be/mQyea9aqbcQ

It’s clear that the guy filming this is a fast rider as he overtakes almost anyone he comes across, and it doesn’t ever seem to be a problem. Having lived in the Netherlands with this type of pervasive infrastructure, I have to say this was much more my daily experience than being stuck behind the huddled yearning slow masses or something. In practice it’s just almost never a problem, even with the fact that most Dutch people tend to cycle at a pretty leisurely pace.

If Rotterdam looks like that with way more density and modeshare than Portland has, I really don’t think Portland’s going to be having pervasive problems with cycletrack bottlenecks.

I get that the egalitarian ideal of everyone sharing the road is great, and actually this really should be the case in many slower streets (cycletracks needn’t go everywhere). To the extent possible I’d even like to see little or no separation between road and sidewalk on some of those to visually “force” drivers in such areas to be “unsure” and consider others.

That being said, we accept that with vast disparities of power and size cars and pedestrians do not belong together in busier higher-volume roads. So since we already accept the provision that sidewalks must be present, the remaining question is—in those scenarios are bikes’ power and size abilities vastly different from those of cars, thus deserving their own separate channel, too? The pragmatist in me that also accepts separation for pedestrians says yes.

But I think you’re making the assumption that cycletracks are inherently more expensive than conventional lanes. For various reasons (especially related to the expense of surface materials/foundations required for conventional lanes as extensions of always-expensive car infra) and the fact that cycletracks require less maintenance they have sometimes even come out to be cheaper than conventional lanes.

“But I think you’re making the assumption that cycletracks are inherently more expensive than conventional lanes. For various reasons (especially related to the expense of surface materials/foundations required for conventional lanes as extensions of always-expensive car infra) and the fact that cycletracks require less maintenance they have sometimes even come out to be cheaper than conventional lanes.”

Do you actually have any proof of this? Moving curbs is ALWAYS going to be more expensive than throwing down some paint. And in Portland it’s always going to be about reconfiguring, not building a new intersection from scratch.

I’m confused by your less maintenance idea. Cycletracks will require specific equipment and personal to clean them. Bike lanes can usually easily be cleaned by standard street sweepers. I’m sure you’re insinuating filling cracks and pot holes? Sure that might be the case in the auto lanes, but a freshly paved bikelane rarely needs resurfacing very often, unless it is a point where auto cross (which a cycletrack will also have).

In central portland we do not have a single major road that resembles the monstrous waste of livable space depicted in your video (nor are there any skyscrapers). Some of the surrounding suburbs do have 8-10 lane arterials but these areas will likely remain hostile to cycling long after portland achieves it’s mode share goals.

Nick, where would you see one of these intersections going in Portland? Clearly it would need to be an intersection with some space to work with? Something like Foster and 82nd? Do you think it could work downtown?

Here’s the catch – These intersections are designed to work with two intersecting cycle tracks. There may be ways to integrate them with conventional bike lanes, but it’s tricky. It will probably involve converting bike lanes into cycle tracks in advance of the intersections.

I’d hesitate to name specific intersections. There are some great candidates in outer east portland if they were paired with road diets to provide buffered cycle tracks, but I’m not so sure this would work well with the narrow, curb tight bike lanes we have right now.

It’s not really the disparity of power and size that’s a problem, it’s just speed. You can drive a compact car on the freeway right next to a double semi-truck, and that’s a HUGE size difference, but it’s no big deal because you’re both going the same speed and traveling straight forward. On the other hand, driving at 30 on the freeway would actually be very unsafe, no matter what size vehicle you have.

A pedestrian, walking can’t possibly keep up with even the slowest traffic, so it makes sense to separate them to the side. On the other hand, bikes actually *can* keep up with traffic, at least on some streets. So I think it makes sense to integrate bikes when possible, and separate them when necessary (whenever the traffic speed is over 30, basically).

Agreed. Even the Netherlands has shared streets. The difference there is that in these “fietsstraats”, cars are treated as guests and people on bikes get priority. This differs from the free-for-all nature of American streets (even the low-volume neighborhood ones).

most of downtown portland is traffic calmed to 15-16 mph speed limit via signal timing. and in the rest of portland the default speed limit is 25 on conventional roads and 20 on bike boulevards.

imo, the best solution for downtown portland would be to make major bike routes car-free or car-light. protected bike lanes are expensive half measures.

That’s a great idea to have friendly flaggers guide people through the process in the beginning. They could reinforce car signals for any confused drivers while also being able to answer pedestrians’ and people on bikes’ questions right there. Cool!

It worked out very well. I suspect some of the flaggers were subjected to abuse at times but they seemed to have some training to deal with that. The ways that opposition to change comes is fairly predictable so it can be prepared for.

I also noticed on another project here, the Comox Greenway, when some crazy woman was yelling from her car window some rant to all the workers who were laying the concrete forms out, one of them went and chatted with her and gave her a business card to contact the relevant city department. It was all very civil and nice.

Sometimes criticism isn’t of the project but is of the process. (Or so the detractors claim when they don’t get their way.) If that’s really the case, then the process should be one that everyone feels included and part of it.

I really like the idea of physically separated cycle tracks. I would definitely ride more if they were available.

I would add my voice to those who expressed concern about autos’ right on red turns. Also, if all motorized traffic is stopped in all directions at the same time, traffic flow is going to be serious impacted, possibly causing serious backups.

Exactly. Each mode of travel is ideally designed for its requirements. It seems to me that comments here against separation have a lot to due with fear of too-close proximity to others on bikes but in practice this is almost never a problem.

As Nick Falbo’s video notes, people on bikes are pretty good at negotiating space and staying out of each others’ ways, and it’s pretty rare to truly be “stuck” behind someone. For that to happen on any regular basis would require modeshare and density way greater than Portland envisions.

If you want to see how congested these curbed cycletracks will get, go to N. Williams or the roads to/from the Hawthorne or Broadway bridges during commute hours. Cyclists are stacked up behind each other in the bike lanes.

Fortunately, with painted lanes the faster riders can take to traffic lanes, either to pass slower riders or simply to ride there.

Now, imagine 4 and 5 times the volume of bike traffic (“build it and they will come”, right?), many of the additional riders being slow ones, and all those bikes trapped in a 4 or 6 foot curbed cycletrack. The quality of riding will be lousy, there will be too much rider-on-rider conflict, and we’ll all have to ride at the speed of the slowest riders. About 12 mph, I observe. Throw in cargo trikes, mobility scooter, someone towing a trailer of kids, and riding a bike will be a frustrating, jaw-clenching slog instead of the fun, fast, exhilarating thing it is today.

John,

Having ridden in bike lanes throughout the Netherlands and Copenhagen, I can tell you that crowded bikeways can quite exhilirating in their own right. You might think lots of people and slower speeds are a bad thing, but I disagree.

We as bicycle riders are no more deserving of an exhilarating ride in clear bike lanes or paths than car drivers are deserving of an exhilarating driving experience like the auto companies habitually show in their TV adverts.

We live in a city. If you commute in it you’re just going to have to get used to being around lots of people that are so inconsiderate as to not get out of your way whether you are riding a bike or driving a sports car. Fast exhilarating driving is out on the country roads; watch for farm implements and Rolling Coal’ers.

Yup, that pretty much sums it up! Living in an urban environment means that somewhere someone might be in your way at some point–whether you’re on a sidewalk, transit vehicle, bike, car or something else. Of course good thoughtful design can and should help minimize these issues (in addition to Portland’s relatively low density in the grand scheme of things), but it’s something that can come with the territory.

You and I will (hopefully) be one of those 80 year olds one day, too, and might appreciate some extra protection. The thing is bike infrastructure shouldn’t just serve the small percentages of us who are healthy and brave enough to bike vehicularly.

And that being said, for those with the need for speed it’s pretty unlikely that any theoretical cycletrack in Portland would be positively crammed with slow bicyclists in any pervasive way. In practice it’s quite easy to pass someone or someone(s) on a cycletrack in any case. In practice a well-designed cycletrack really is much more liberating than confining.

But with smart signalization you wouldn’t have to *always* stop before making any left turn. With timed signalization + protected intersection you can often sail through and it’s still green for you to turn left once you reach the other side. It’s basically a squarish roundabout.

While making a vehicular left you have to stop sometimes, too, when the light is red. So I just don’t see the issue.

And btw, in designs as in the video as a bike on the cycletrack you always get a free right on red which you don’t get (at least not legally) when you’re biking vehicularly and want to turn right on a red.

As someone who also absolutely used my bike living in the Netherlands to get places in small amounts of time (nothing like that adrenaline rush as you race to an appointment) I can confirm that even in my experience doing this all the time (because I’m often cutting my timing a bit close) in Amsterdam and other parts of the Netherlands I almost never felt constrained or slowed down by others. It’s really easy to pass people and people do it all the time. In practice it’s not constraining or speed-inhibiting at all.

“…The thing is bike infrastructure shouldn’t just serve the small percentages of us who are healthy and brave enough to bike vehicularly. …” Gezellig

Nor should it just serve people choosing not to ride briskly. On the several of Portland’s central city heavily used bike lane equipped bike routes, there’s already been considerable friction between people riding at relatively slow speeds of say 10-12mph, and those that want to travel 15-20. People in comments to this weblog, say they don’t like other people passing them swiftly in close quarters.

Here’s bikeportland’s Jonathan Maus in his comment just above, seeming to say he likes riding on crowded bikeways: “…Having ridden in bike lanes throughout the Netherlands and Copenhagen, I can tell you that crowded bikeways can quite exhilirating in their own right.”.

Exhilarating? I wonder who for…the majority of people riding there? Or just the occasional person on vacation riding amongst them, dazzled by the sensation of crowds of people biking on infrastructure different than that of U.S streets and roads. El Biciclero’s comments suggest he’s not so enthusiastic about having that kind of exhilaration imposed upon him.

In Portland, instead of many cycle tracks, just a basic, non-obligatory cycle track system built of maybe two east-west, and two north-south tracks, could be a good start to give residents an idea of how that infrastructure may work for them. So far, interest in that sort of thing here doesn’t seem to be strong. Same probably applies to complex intersection treatments designed to better support bike travel.

Ha! Now, see? Here you and I appear to agree to a ‘T’. The “small percentage” argument can be made both ways, and the assumption that all this passing and lack of crowding will be true assumes that a facility is built with sufficient width to accommodate passing. It also assumes that those being passed will be comfortable being passed with inches to spare. We often forget that in the U.S., many of the slower riders we might hope to entice onto separated facilities are also folks who haven’t ridden a bike in 15 or 20 years, if ever. That kind of true “newbie” rider will require a much wider berth for passing than a typical Dutch rider, who learned proper cycling in school and has 15 years of experience doing it, not 15 years of neglect to make up for.

My thought is this (intended more as a response to Gezellig than you, wsbob): as an example, I know people who are afraid to drive, say, over the Marquam bridge, or even afraid to drive on the freeway in general. I also know that I can choose between the freeway and parallel surface streets. Drivers have a choice about where they drive and can choose a route with which they are comfortable. If I’m driving to a particular destination, I can decide whether I think a freeway or surface streets will be faster, and choose my route accordingly. Should I not have the same freedom of choice if I ride my bike?

One of the big objections to a “road diet” on Barbur Blvd. is that if that roadway were narrowed to a single lane for any distance that poor drivers would then be “limited to the speed of the slowest vehicle” because there would be no way to pass (or at least not another same-direction lane to pass in). Would not forcing cyclists into a protected cycle track do the same? We’re willing to put this limitation on ourselves in the name of “safety”, but we can’t expect drivers to be similarly limited for the sake of cyclist safety? Wow.

I’ll just highlight a couple of terms from your comment:

“Well-designed”, and “smart”. Around here, these are gigantic assumptions. I will be so bold as to predict that nothing as “well-designed” or as “smart” as you are describing will ever be built in Portland or surrounding suburbs in my lifetime. What I expect in my lifetime–I will also be so bold as to predict–is being subjected to a series of ill-conceived, poorly-designed cycling “facilities” that I will be legally forced to use, even though they do nothing but make my trip slower AND more dangerous, all the while reinforcing the idea to the general public that bicycles and the people who use them are inherently less important than cars and their drivers–and their primary responsibility when cycling is to stay out of the way!

As I mentioned in a separate comment, until the cycling facility is built that actually prioritizes cycling (not just perceived cycling “safety”) and gives me a real advantage over choosing to drive my car, I will remain very, very skeptical of any facility design, and the motivations behind the design (most designs have the aim of getting cyclists out of the way of cars as cheaply as possible, even though they are sold as “safety” improvements), and will seize any opportunity NOT to use such “facilities”.

Whenever a street comes up for redesign, curbs and lots of things get torn up anyway. A lot of conventional lanes built in recent years in the US have been the result of money-requiring road diets that were going to happen anyway. Then they striped a conventional lane because that’s what standards say to do.

Regardless of how you feel about the design of Cully, for example, I do remember it being mentioned on Bike Portland that the cycletrack option ended up being cheaper than a conventional lane studied for that stretch would have been.

Some cars and trucks do obliviously veer onto painted conventional lanes, so the wear-and-tear does add up, especially since those heavy vehicles can’t veer into a separated cycletrack.

As for specific equipment and personnel and costs for cycletracks, it’s hard to find many places that talk about costs, even in Dutch. (Most of the articles I could find about ongoing city costs related to bikes had to do with the nuisance of dealing with all those abandoned bikes being left places so that seems to be of greater concern).

Cycletracks there seemed in general a bit cleaner in comparison to sidewalks–not sure if this is because people whizzing by all the time cause any loose papers/trash to end up elsewhere.

Most the projects I’ve read about or attended meetings for in Portland have been reconfigurations where the road surface is not altered. SE Foster for example. It was going to cost millions of more dollars to move the curb and add a cycletrack, compared to the thousands it will cost to stripe some bike lanes.

Portland is pretty filled in at this point. Most streets are going to need to be redesigned or retrofit. From a financial standpoint for these types of roads the bike lane is always going to be substantially cheaper (sometimes by two magnitudes).

And again, I would urge you to actually use the “Reply” button on these threads. It actually keeps stuff in order.

That vid wasn’t to compare roads or building heights per se but what 25% modeshare can look like in a city with roughly the same population as (and even greater density than) Portland.

Yes, I don’t think anyone thinks there should cycletracks on every street ever. There are lots of other smart things cities can and should do depending on local context:

-> road diets

-> bike blvds/neighborhood greenways

-> allowing contraflow bike lanes on one-way (for cars) streets

-> one-way street for cars whose flow alternates every block or 2 to allow local car access but prevent thoroughfare-type activity

-> banning cars outright on some streets

-> retractable bollards restricting certain streets to cars only at certain hours, etc.

The fietsstraat and its related cousin the woonerf are also *great* examples of non-protected infrastructure that can work really well.

But protected infrastructure should absolutely be considered in some high-stress environments where these types of treatments won’t work.

A bridge is a natural bottleneck so I’m not sure if comparing roads near one and at rush hour is necessarily a representative indicator of how an average protected lane in the city will be performing.

That being said, beefing up infrastructure on and near the bridges is clearly of importance, too.

Those studies compared German and Danish versions of cycletracks with conventional lanes. German and Danish cycletracks are indeed often subpar as they expose cyclists to unnecessary danger and stress. They should not be copied.

German cycletracks are often narrow and much more likely to be within the doorzone of parked cars, and both German and Danish cycletracks usually suffer from unprotected intersection design.