key role in the bill’s passage.

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

A new state law signed Tuesday will let Oregon cities name narrow side streets where, for the first time in decades, people on foot won’t be required to yield the roadway to drivers.

The bipartisan bill sailed through the statehouse this spring with backing from the City of Portland, the League of Oregon Cities and advocacy group Oregon Walks.

“The law is the first of its kind in the nation,” Portland pedestrian coordinator April Bertlesen wrote in a celebratory email Wednesday.

“When I was young… we would walk side by side, which technically is not lawful. But when you’re eight, you’re going to hold your grandma’s hand.”

— Stephanie Routh, Oregon Walks

“It memorializes in law what Oregonians have come to do on their home streets anyway,” Oregon Walks Director Steph Routh said Thursday in an interview. “When I was young and visiting my grandparents in Wheeler, Oregon, we would walk side by side, which technically is not lawful. But when you’re eight, you’re going to hold your grandma’s hand.”

According to Ray Thomas, a local lawyer and expert on walking laws, “The old law gave no legal standing to pedestrians in the roadway relative to motor traffic and required them to always yield the right of way unless in a crosswalk.”

The new law, which cities will be able to apply only on residential streets that are no more than 18 feet from shoulder to shoulder, requires signs alerting road users that pedestrians (a term which includes people in wheelchairs and similar mobility devices) may be present. It also forbids pedestrians from creating a “traffic hazard.”

Routh said the new law lets cities legalize many other activities, too – not just transportation.

“I think we can all easily remember a moment in the recent past when we have seen a parent pushing a stroller down the roadway to the corner grocery store, or when we have passed a few kids shooting hoops on a side street,” she said in her testimony prior to its passage.

In general, Routh said Thursday, the new law “looks at narrow residential roadways as places that connect people.”

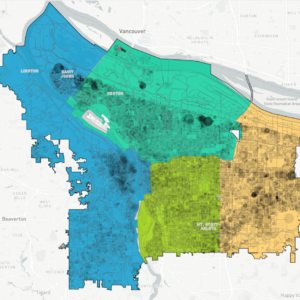

Though the law extends the humans-welcome spirit of Portland’s neighborhood greenway network, it won’t apply to most neighborhood greenways, which are wider than 18 feet. Routh said that in Portland, it’s likely to be a better fit for narrow and unpaved streets in parts of Southwest and East Portland that were developed when still outside the city limits. In the legislature, the bill’s sponsors were Sen. Ginny Burdick (D-Southwest Portland), Sen. Betsy Johnson (D-Scappoose), Sen. Chuck Thomsen (R-Hood River, whose district extends to Portland’s eastern suburbs), Rep. Carolyn Tomei (D-Milwaukie) and Rep. Chris Gorsek (D-Troutdale).

The City of Portland prioritized the bill as a key part of its “Street by Street” program, a recent effort to help neighborhoods make themselves more pedestrian-friendly without having to find money for sidewalks, which cost $1 million or more per mile to install.

Routh said Oregonians shouldn’t see the bill as an reason not to create better sidewalks or roadways, but rather a reason to look for new ways to design and think about streets where sidewalks are, out of necessity, absent.

“In a financially constrained environment, we can’t assume that we’re going to see sidewalks on every street,” Routh said. “Innovative solutions are needed, and sharing the roadways just makes sense.”

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

This is fantastic public policy! Many thanks to all those who worked hard to make it happen.

wait a second… Pedestrians were required to yield to cars? I presume this rule applied everywhere except where a crosswalk is? (marked or unmarked)

I applaud the sentiment, but it would seem that if cities can decide this vs. that street applies the law, it would be a confusing mess. Most citizens don’t know the basic laws that apply to all streets, let alone the specifics of who has the right of way on one specific street the city has deemed appropriate and not the next street over, that might have the exact same configuration. It would seem more appropriate to say that on any residential street without sidewalks, a pedestrian ALWAYS has the right of way, as long as he/she is positioned to the far edge of the roadway.

are we suggesting that pedestrians are now like cattle? Quel un insult!

“The new law … requires signs alerting road users that pedestrians … may be present”

That’s silly. Americans love all those warning signs, don’t we.

I applaud Oregon Walks for making this happen, and I’m surprised to learn it wasn’t the law already.

I’m surprised it passed.

It makes too much logical sense to believe that it survived a body of lawyers turned wheeler dealers.

Where can I get a t-shirt with one of those signs printed on the back? It might not be legally a sign, but maybe motorists will think that it is. 🙂

There are a few streets near me in Kenton that fit this description. Not sure if they’re exactly less than 18 feet, but I think they may be. For example, N Farragut here: http://goo.gl/5ACSx . There’s often no sidewalk on these streets, so people freely use these streets to walk on anyway. The narrow width really makes the street feel more intimate and less captive to automobile traffic.

Time to narrow up streets to 18′

18 seems a bit restrictive…

Isnt the minimum width for a modern suburban residential street 36 feet?

That may be true now, but much of Portland was developed before these minimums were required since they were unincorporated at the time. Many neighborhoods only have a 16′ foot wide swath of pavement without sidewalks, if anything at all. Currently it costs over $4 million per mile to to upgrade to city standards, which the home owner is required to pay. For 50 feet of right of way this would cost an average home owner about $300 a month over 20 years for the upgrade to city standards. Obviously, out of the range of the average low income household….as these neighborhoods tend to be lower income.

That’s such a glam shot of the lovely and talented Ms. Routh!

Now if we could only train pedestrians to use the sidewalks instead of walking down the middle of the road.

It’s a nice idea, but my bet is zero enforcement, zero compliance, zero change.

My sentiments as well. Drivers will continue to strike and kill pedestrians. We already have the vulnerable road user’s law and to the best of my knowledge it has never been used to convict a driver who injures a cyclists or pedestrian (or motorcyclist).

Perhaps the true idea here is not enforcement/ticketing/revenue, but simply reaffirming public awareness and affecting outlook.

Nice idea, but it won’t change anything. What pedestrian is going to be crazy enough to face down a driver in a car? This is one of those things that look great on paper, but will end up being worth the paper it’s printed on.

“Pedestrians were required to yield to cars?” Um, yes, unless they are on a sidewalk or legally crossing at a crosswalk, pedestrians on public roads are indeed required to yield to cars.

So this is a HUGE change, although the 18 foot requirement is very tight, effectively half the width of a standard residential street.

BTW, pedestrians were not required to yield to cars until to the 1920s, when the then-new AAA lobbied legislatures across the nation to effectively transfer ownership of the streets to auto drivers.

Right. That’s what I said in the rest of my comment.

“I presume this rule applied everywhere except where a crosswalk is? (marked or unmarked)” e.g. in a crosswalk, cars must yield to pedestrians. That is the part that wasn’t reading clearly in the article.

Thanks for the fun fact about this not being in effect until the 1920’s. –very interesting.

Freeloading pedestrians.

We ought to require them to pass tests, get licenses, pay usage fees, and wear helmets and blinky lights.

We pay for everything and they take our streets. Jerks.

(noting sarcasm, in case internets don’t portray it)

That’s great! I always thought that we should not worry about adding sidewalks to many of our SW Portland streets without sidewalks, but instead turn them into German style Spielstrasse (play street) or dutch style woonerfs. All we need is to limit the speed limit to “walking speed” (5 mph) and make sure driving fast is difficult. We could do that by forcing cars to “meander” around planters or alternating parking and by adding speed bumps. If then kids start playing on the streets again, we have won the battle. Several streets in SW come to my mind, e.g. Bertha Blvd between 23rd and 33rd (aka little Bertha) or streets around Hayhurst elementary.

Yes! The place to start would be a map of all the places in Portland the new law applies, and a campaign to expand it.