as envisioned in Metro’s plan.

Metro will host an open house tomorrow (5/23) for their Regional Active Transportation Plan. The plan will be the region’s first specifically tailored to bicycling, walking and access to transit. The planning effort has been underway for well over a year and is set to wrap up by the end of next month. In summer of 2014 the plan’s recommendations and a list of prioritized projects will be proposed for adoptions into the Regional Transportation Plan.

The plan’s ambitious scope includes: the creation of a new set of design guidelines for bicycle facilities; an update to regional biking and walking maps; integration of the existing active transportation network; identification of a network of ‘Regional Bicycle Parkways’; a recommendation of strategies for implementation, and more.

In other words, this is a big deal. As its projects get adopted into the RTP, Metro’s Regional Active Transportation Plan will give regional policymakers the crucial political breathing room and decision-making framework they need to make real and significant investments that could vastly improve bicycling conditions.

In developing the plan, Metro created an existing conditions report that laid out the massive potential and challenges our region has for realizing a transportation system that is more oriented toward bicycling and walking. Here are some of their findings (taken from their own Household Activity Survey, the State of Safety report, and Opt-In survey results):

- bicycling is growing at a faster clip than any other mode in the region;

- of all the bike trips made in the region, 58% are made by people with an income of $75,000 a year or less;

- 75% of our region’s bike trips are made by “white persons” and 25% are made by “non-white persons”;

- however, “non-white persons” make a larger percentage of their trips (3.3%) by bike than “white persons” (2.7%);

- women make 35% of all bike trips in the region;

- about 59% of all auto trips in the region are under three miles;

- only 34% of all bike trips are for work, while 53% are for social events, errands, or recreation;

- while 18% of all trips in the region are made by bicycling and walking, they get only 3% of capital transportation funds;

- Portland has 68% of the entire region’s serious bicycle crashes;

- over 52% of all bicycle crashes occur at intersections;

- an average of 88% of survey respondents from Clackamas, Washington, and Multnomah said they are either “somewhat” or “very” interested in biking more often for transportation.

To develop the regional active transportation network, Metro kept the above findings in mind and overlayed them with a list of over-arching principles (like making facilities safe, connected and easy-to-use) and an evaluation criteria. The four main evaluation criteria were: access, safety, equity, and increased activity (as in, does the network increase the number of bike/walk trips).

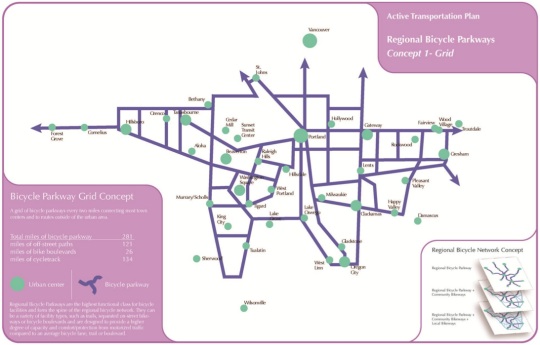

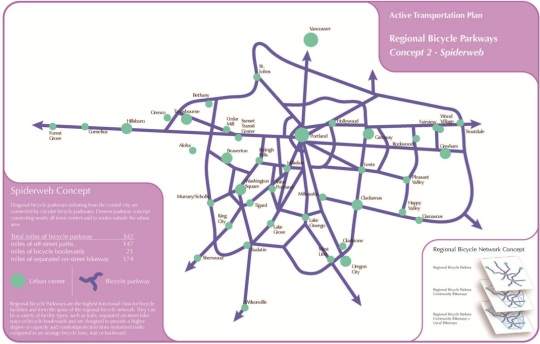

At the City of Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee meeting last month, Metro’s Lake McTighe, a project manager in their active transportation department shared the three “network concepts” they have come up with in order to model performance against the criteria. The three concepts (see below) are made up of “Regional Bicycle Parkways” which Metro describes as, “the highest functional class for bicycle facilities” that “form the spine” of the network.

There’s the “Grid” concept:

The “Spiderweb” concept:

And the “Mobility Corridors” concept:

Metro analyzed each of the concepts to determine how each one influenced the rate and nature of bike trips. Another important part of this plan is Metro’s use of a bicycle traffic demand model. This is a big deal because transportation planners have never had a way to test how different types of facilities impact bicycle traffic. Auto traffic demand models are very sophisticated and they dominate transportation planning as a result. Metro has been working with researchers at Portland State’s Oregon Transportation Research Education Consortium (OTREC) to create the model and it’s finally starting to bear fruit. McTighe says they can now use the took to “look at how bike project might create new bike trips, change trips from driving to biking” and so on.

Another tool Metro is rolling out in this plan is the “Bicycle Comfort Index”. This tool can also give them a more sophisticated understanding of how different network concepts and facility types will impact the rate and nature of bicycle use. They use auto speed, auto volume, and the number of lanes on a roadway to determine a route’s BCI value. “We’re interested in getting at that 60% of people that are “interested but concerned” so it’s about understanding that the existing of a bike lane isn’t enough to make people feel comfortable bicycling. We’re not just saying, ‘OK, we’ve got a bike lane so we’re done.'”

All this analysis can tell Metro where the high demand routes are and whether or not those routes are comfortable to bike on. If they find a high demand route with a low comfort index score, a project that improve bicycling on that route could be bumped up on the priority list. (One of the interesting findings so far is that diagonal routes, regardless of whether a bike lane is present or not (like Sandy Blvd), show high bicycle traffic demand.)

There’s a lot more to this plan than I’ve outlined. Before you go to the open house tomorrow, your homework is to check out the PDF of McTighe’s presentation to the Bike Advisory Committe last month. I also asked McTighe this morning what she’s most interested in in terms of feedback. She said they are still developing the recommend networks and how projects should be prioritized and she shared a list of questions they’d like your answers to:

- How complex and dense should the regional bike and pedestrian networks be (keeping in mind that we want to prioritize and focus investments)?

- How important is the quality of the experience (quiet, comfortable, green, wide path) compared to utility (directness of route, ease of reaching destination)?

- What is most important when considering location routes: nature beauty (near trees, rivers, and so on); direct access to shops and restaurants and services; separation from traffic; complete protection from traffic even if taken somewhat out of direction; avoiding hills?

- What are the highest priority projects people would like to see built?

Be there:

-

Regional Active Transportation Plan Open House

5 to 7 P.M. Thursday, May 23

Metro Regional Center, Council Chamber (600 NE Grand Ave)

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Fantastic!

Too bad ODOT can’t think this way.

“while 18% of all trips in the region are made by bicycling and walking, they get only 3% of capital transportation funds”

Good statistic to have on hand. But it is worth noting that the 3% of funds that are spent on those human powered modes are mostly spent to keep the ubiquitous cars a few feet further away from us, I’m pretty sure most of all funds spent on, say, car infrastructure do not go to keeping those dangerous bikes away from the vulnerable car occupants.

“of all the bike trips made in the region, 58% are made by people with an income of $75,000 a year or less”

Is that appreciably different than the income distribution in the region?

but that assumes that every dollar spent on transportation only supports one mode of transportation.

Streets that are built without bicycle infrastructure can still be used by cyclists. Streets without sidewalks can still be used by pedestrians

“but that assumes that every dollar spent on transportation only supports one mode of transportation.”

What I said does not assume that.

“Streets that are built without bicycle infrastructure can still be used by cyclists. Streets without sidewalks can still be used by pedestrians”

Absolutely though, again, because of the overwhelming presence of the car, neither walking or biking there is likely fun or inviting to the less bold. But that has nothing to do with the quote I started with which suggested that “[biking and walking trips get] only 3% of capital transportation funds.” Thanks to the likes of Beth Slovic, many are inclined to think of a dollar spent on bike infrastructure as being in some unqualified sense ‘for bikes.’ I am allergic to that, as I explained above.

Some transportation dollars are spent in ways that exclusively benefit only one mode, and typically also disbenefit others. Freeway expansions, for instance.

Other expenditures, typically those classified as ‘for bikes,’ are defensive and would be absurd if it weren’t for the overwhelming presence of cars on our streets. Transportation dollars spent ‘on bikes’ thus don’t provide the same unqualified exclusive modal benefit that a freeway expansion dollar does, but are rather a paltry gesture at undoing some of the historic asymmetry in funding, priority, safety, etc.

We can think of transportation spending in a whole bunch of ways.

– by mode share;

– how well modal spending matches mode share/modal trip count;

– by how well they measure up against a no regrets scale;

– whether we can afford it;

– etc.

ODOT seems to pay rather little attention to any of those as far as I can tell. But I’m delighted to read so much encouraging from Metro about this.

Jonathan,

thanks for the great story and plug! We hope to see a lot of people at the open house to provide comments and input.

One correction:

“•about 59% of all auto trips in the region are under three miles;”

it is actually:

Over 66% of all trips made by autos within the 4-county area are less than six miles in length, nearly 44% are less than three miles in length, and nearly 15% are less than one mile in length.

Love it. LOVE it! Would love to see that Spider Web concept implemented but I’ll take any of the three if we can get them.

“How complex and dense should the regional bike and pedestrian networks be?” I think we need to start with something more sparse and doable like the “Mobility Corridors” concept above, but have a longer-term goal of something more dense like the spiderweb concept (which I prefer because I think Portland will always be the hub of bike-trip demand in the region).

“How important is the quality of the experience compared to utility?” Utility has to take a higher priority than the quality of the experience, but quality shouldn’t be compromised below a certain level. Some meandering to avoid busy roads and intersections is to be expected, but if the goal is to encourage people to get out of their cars — and it is — then the routes have to actually get people where they’re going without meandering too much.

“What is most important when considering location routes: nature beauty; direct access to shops and restaurants and services; separation from traffic; complete protection from traffic even if taken somewhat out of direction; avoiding hills?” I’d say direct access to services and separation from traffic are tied for top priority, followed by avoiding hills (for less-fit cyclists a longer route that avoids a big hill can take less time to ride than a shorter one that goes right over the top). Complete protection from traffic is nice, and may be key for many cyclists, but difficult to achieve in a lot of places. Nature beauty is nice for families having fun on the weekend, and has traditionally been the emphasis of many MUPs, but isn’t going to get people riding to the cafe or grocery store.

“What are the highest priority projects people would like to see built?”

I think the regional or interurban corridor that, by far, has the most unmet demand, is the Portland-Westside axis. NOT coincidentally, this is my own commute. There’s no getting around the fact that there’s a mountain range in the way, along with Portland’s overwhelmingly least bike- and pedestrian-friendly (SW) quadrant. There are NO routes over the West Hills that are safe enough for a big chunk of the interested/concerned demographic AND avoid massive hills. Pick your poison. If I’m in a hurry I’ll take the Beaverton-Hillsdale or Hall-Olsen-Multnomah-Barbur corridor, knowing they put me at more risk but I’ll get home faster and with less effort. If it’s a dark and rainy winter evening, say, and I’m more concerned with safety than speed, then I’ll take Park and the US26 bike path to the Zoo, or one of the steeper circuitous routes through the back alleys of the West Hills. But even those routes have to traverse some really dicey choke points that would deter less confident cyclists, and are difficult to figure out for the n00bs we want to attract to them.

Most specifically I’ll also put in a plug for the Bethany-St. Johns route shown on some of the concept maps. This so-called “Forest Park Connection” is IMO the most desperately needed missing link. Take the conundrum faced by commuters over the more southerly parts of the West Hills and double it: the more direct eastbound routes from the westside to Skyline are exceptionally busy, narrow and dangerous; and the safer, quieter routes are exceptionally steep.

Given the demand for and crowding on MAX trains, we might also want to consider a West Hills shuttle as part of our Regional Bike Parkway system. This has long been at the top of my “what would I do for my community if I won the lottery?” list.

Dear GlowBoy,

thank you for your input! A connection between the Westside and Portland showed up as one of the highes demand routes in the bicycle modeling, along both Hwy 26 and Barbur/Hwy 99.

I’m sure most here have already seen this: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Friends-of-Barbur/123436277720183

There is effort underway within the City of Portland to advance Barbur (HWY99) as a better bike street.

If this is such a “big deal”, then why have we not heard of it until about a week and a half ago? I have something else scheduled because this was not even known until very recently. If you want people to attend an event, especially in the summer (spring?) you have to give more than two weeks’ notice.

Actually, there was a presentation on this at a Pedestrian Advisory Committee. I could have neglected to write down that date.

Great news. I wonder if Metro can use any of the $50 million in green spaces money that just passed to build trails?

Glad to see the “bicycle comfort index” exists, even if it seems pretty subjective. It’s crazy that a five foot bike lane on TV highway shows up as equivalent to, say, the bike lanes on Williams/Vancouver.

Dear Andrew,

the BCI is definitely not perfect. We are aware that the index, for instance, does not account for the design of facilities, which is of course paramount. In future analysis we would like to include data on the width and quality of on-street facilities but that data does not exist at a regional scale, unfortunately. One of the recommendations of the plan is to explore collecting that level of data for future planning and project development.

I am far to “infrastructure stupid” to grasp all of the details evolved in things such as this to comment, but….

You wonderful transpo-wonks blow my mind!

Keep up the good work, I bet something wonderful will happen….

Until then,I will keep JRA-ing around in quiet, ignorant “vehicular cyclist” bliss, as it is all I have ever known.

.. I am also “far TOO” stupid, … oops. 🙂

I think the spiderweb concept is the best one to shoot for; it makes the most connections, making it easier for people in the outlying parts of Metro to get to a variety of places besides just Portland– many of us out here never go into Portland, except for rare recreational activities like Cirque, concerts at the Rose Quarter, dinner out at a fancy restaurant. A lot of us are quite happy to live, work and recreate in our suburb. But we can’t get from one part to another out here very easily because of gaps in the system.