(Image: League of American Bicyclists)

Bicycling offers American towns and cities a huge return on investment; but one of its benefits that often gets overlooked in debates over spending choices is just how good a value it is from an infrastructure spending standpoint. Compared to costly highway and transit projects, creating bikeways that can efficiently move thousands of people through our towns and cities is extremely affordable.

made possible by:

- Planet Bike

- Pro Photo Supply

- Readers like you!

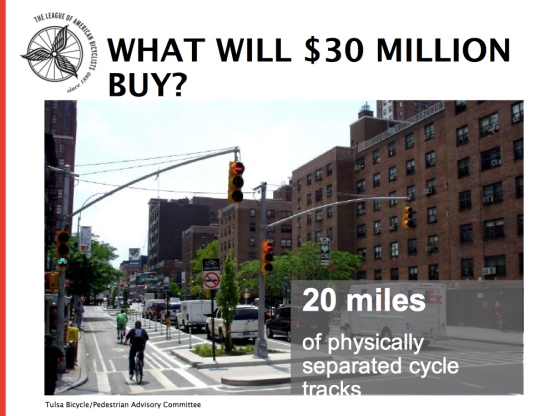

We learned just how affordable in a breakout session at the National Bike Summit on Tuesday titled, Bicycling Means Business: Getting the Facts Straight. League of American Bicyclists’ Policy Director Darren Flusche shared a presentation that included a series of slides under the heading of “What will $30 million buy?” I thought it was a great way to conceptualize the affordability of bicycling, as well as give important context to the trade-offs we make when we spend money on road widening projects.

The $30 million number was also interesting to me because that’s about what Oregon will have to pay each year (for 30 years) to repay the proposed loans for the I-5 freeway widening and bridge replacement mega-project (a.k.a. the CRC, but don’t get me started).

As shared by Flusche, for $30 million we can either have one mile of freeway widening or…

0.5 miles of new MAX light rail line (OK, I threw this one in just for fun),

or 600 miles of quality bike lanes,

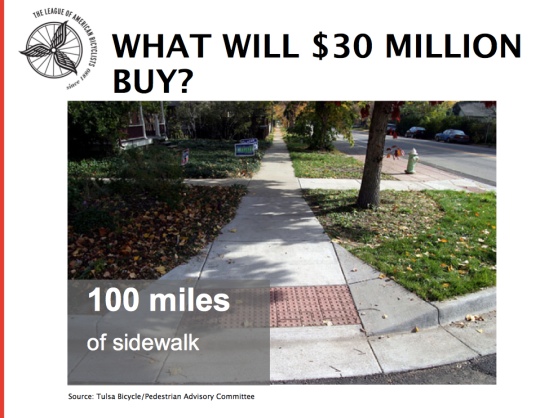

or 100 miles of sidewalks,

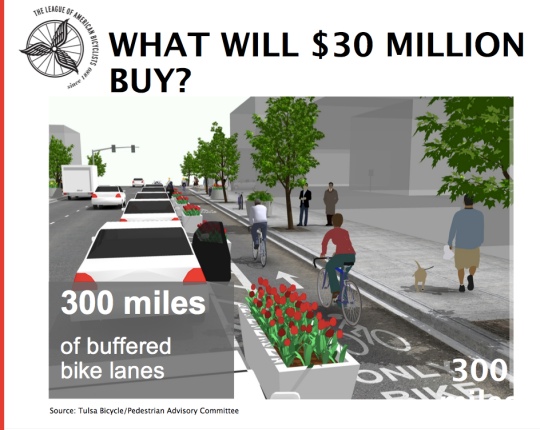

or 300 miles of buffered bike lanes,

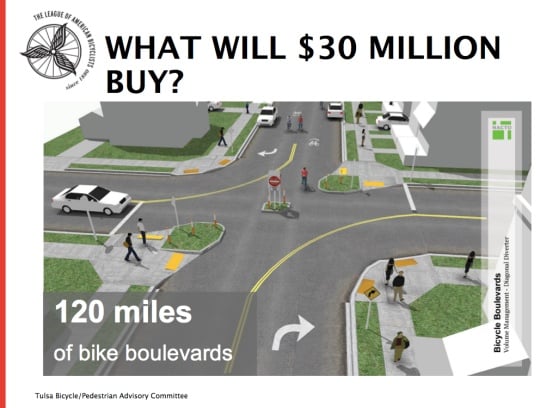

or 120 miles of bike boulevards,

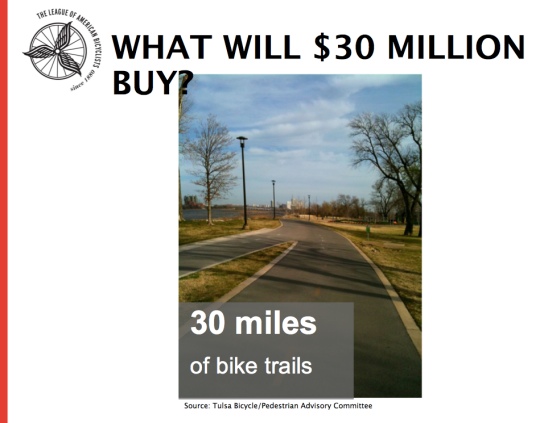

or 30 miles of bike trails,

or 20 miles of physically separated cycle tracks,

or 2,000 rapid flash beacons,

I realize transportation investment is not always an either/or proposition. But as we face budget challenges, we need to stretch our dollars as far as they can possibly go. And it just so happens that investing in bikeways is the best transportation ROI out there.

More 2013 Bike Summit coverage here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

bike lanes and boulevards aren’t a fair comparison because the asphalt is already there… the only fair comparison is to separated trails.cycle-tracks… granted, it’s still a LOT cheaper building for bikes…

Hm. I guess, in looking for the fairest comparison, one could try the following:

What does it cost to facilitate the movement of 1 million person-miles in cars? On bikes? On MAX? On foot? Approaching it this way, including maintenance, highlights what we all know, but sometimes may not have at our fingertips, that the infrastructural requirements go up exponentially as the speed and complexity of the hardware increases.

1 million person-miles accomplished on foot doesn’t need to cost a dime, when you stop and think about it (if we eliminate the car menace).

1 million person-miles on a bike could similarly cost next to nothing in the absence of the need to protect ourselves from the car. How much did China of Vietnam in 1960 or 1980 spend on infrastructure specifically for bikes (or per passenger km)?

But when you get to cars, I don’t think there is a way to subtract out any cross-modal interference because cars themselves necessitate the expensive infrastructure.

With rail it is probably even more costly per passenger mile.

It costs much less to maintain a bike lane than a car lane.

The asphalt is already there, but how do we use it? Generally, money is spent because there is congestion. You can spend $30 million to widen the road, but there could be other ways to fit more people. You could remove street parking, you could paint bike lanes, you could paint bus-only lanes. All are perfectly valid options for expanding capacity. Just because an option doesn’t involve pouring concrete, doesn’t mean that it shouldn’t be considered.

rapid-flash beacons, training motorists to only pay attention to lights and signs…

I’d be curious, a la Michael Anderson’s recent fabulous graphic exploring where Trimet’s money goes, how it is spent, where the $30M for 1 mile of highway expansion goes? How much to labor, pensions, materials, interest, etc. Anyone have a good source on that?

Similarly, the $250K I’ve heard for installing a traffic light. The number seems astronomical to me so I’d like to know how it breaks down.

Thanks.

Estimates aren’t done that way. separate items that make up the whole are bid on. Labor in a bid relates to design and managment only, not the contractor work. Materials costs and labor are included in prices the contractor bids. You’d need to have a contractor tell you their labor costs as a percentage of each bid item versus materials and sum them up. But it doesn’t stop there. The supplier of the poles has labor and materials included in the price charged to the contractor (plus profit). It keeps going.

Are you really trying to tell me we can’t identify the components of the cost to widen a mile of road or install a traffic light? I’m not saying it is something you or I could necessarily figure out on a napkin in a restaurant, but it is surely something someone has or could calculate for us.

I, too, would love to know why these things cost what they cost. Why does 4 feet of asphalt with a white line cost $50K per mile? I dunno. But if experience has taught me anything, it’s that other people’s jobs are seldom as simple, quick, and easy as we tend to perceive.

Payroll hours hike prices pretty quickly. We have yet to find a way to outsource the re-paving of Burnside St. and we don’t get to pay road crews $0.50 per hour here in good ol’ Canada’s sofa. There are many expenses involved in the building of anything expected to withstand the abuse of 2-ton vehicles repeatedly battering its surface. People go to school for up to a decade to learn how to effectively plan such projects.

A complete breakdown of each and every final price tag mentioned here may not be a realistic expectation.

I found this link “Estimating Road Construction Unit Costs”

http://www.fao.org/docrep/T0579E/t0579e06.htm

I’ll leave it to some one else to do the math included there.

Considering what just $30 million buys almost seems quaint now that projects with BILLION dollar price tags are in the offering. But I guess spending that much money on 10,000 miles of sidewalks would be crazy.

It would also make a great point to include what the maintenence costs are for each purchase. PBOT estimates $85 million needed per year to maintain our roads.

The subject you reference is called ‘life-cycle cost analysis’ and is used to compare two or more choices on an equal basis of a common time period. Life cycle cost analysis covers the first cost, plus the operation and maintenance costs, plus other user benefits or costs based on the different choices. Delay is a cost, crashes are costs, and some choices have more or less delay, crashes, pollution…

Nice comparison. Even Max benefits active transportation by getting cars off the road.

It would be well worth it for ODOT to study how much it saves the city when biking over bridges, like the Hawthorne, versus driving.

Like, take 100 virtual commuters. What impact and difference does that have when they are taking bikes versus driving. Not just space consumed, but the impact on the associated traffic flows all over the city as those 100 bikers/drivers commute.

It really needs to be driven home that the more bikers we have, the better traffic gets for all other users of our roads. The more bike protected lanes, the less need for parking spots, for lanes, for cars/etc. I don’t understand why there is such rage for bikers. Every biker is one less car to get in your way!

The cost to vilify bicycle riders (any out group really) is very low compared to the return from the talk radio crowd for doing so.

The South park blocks should be Portland’s first car-free streets downtown.

@Hart Noecker

That would be dreamy. The north park blocks would be wonderful too but access issues to the Portland Art Museum and the Arlene Schnitzer Hall might make that less feasible.

The art museum is on the south park blocks, not the north park blocks, and it is surrounded by three other streets in addition to SW Park.

Both the museums and the Schnitz are easily accessed from other streets with higher car/street car capacity. The park blocks serve as little more than a parking lot for these destinations. Like European cities, Portland should be reducing the number of downtown parking spaces each year. Cars simply don’t belong in urban cores, and the park blacks are a slam dunk for the first series of car-free streets.

That’d be nice but the Park Blocks are already nice. How ’bout taking cars off the transit mall (like it used to be) and devoting that left lane entirely to bikes (and, I suppose, cabs)?

That graphic for the “buffered bike lane” is not accurate when you consider Portland just spent over $200,000 on the Multnomah Street project (which is a mile long if you start at NE 21st and 0.7 miles long if you start at NE 15th – I haven’t been east past 15th since the improvements so I’m not sure if they extend beyond that street).

Jonathan, seems like forgot the attribution and license for the picture of the MAX train.

That one “measly” mile on Yale in Tulsa, OK goes over a very steep hill on two lanes, not easily negotiable by most bicyclists. Most of it is right of way acquisition in high dollar neighborhoods. But, yeah, I get the point. South Yale Avenue is Tulsa’s CRC.

Or the numbers are cooked and distorted by this advocacy group just like the CRC advocates’ numbers.

Let’s assume for a moment that they are cooked. What does that change about the basic notion that underlies the argument? That bike and pedestrian infrastructure costs pocket change compared to autos-first infrastructure.

It’s essentially an efficiency argument. When those numbers are wrong, the efficiency argument is undermined. Then, there’s the whole question of what exactly required $200k? I rode that improvement tonight and its just paint, pavement grinding to remove the previous bike lane marking, and some concrete planters. For 0.7 miles. Is that efficient?

Like with so much these days, you and I and a couple of friends could rent some equipment over a weekend and probably accomplish much of what costs the taxpayer thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars. Does that mean we don’t need the city government? Opinions diverge. You might want to factor in all those meetings, and the public outreach, and the staff time that went into the meetings about how to reconfigure NE Holladay which was hijacked by those fatcats from Ashforth Pacific….

None of that is efficient. But I’m not so sure that is necessarily an argument against non-cars-first infrastructure.

Baby, Remember that The Multnomah seperate lane is COVERED in point. There is all kinds of paint going on in/around that lane). Compare that to the above picture of a bike lane, where they are only using planters for the divider (and likely a little paint at intersections). That is probably a good bit of the difference. That thermo-paint is not super cheap (one of the reasons the intersection bike boxes are a little pricier than most would like).

Sorry, that is supposed to say “covered in paint”.

Hello to Canada (?),

I read only a little bit of your discussion. I think, one thing is great: you are talking about a change in traffic-politics and -planning. This is the right direction!!! And the change will come, if the people USE their head and than USE their bikes. The benifit of an invest in whatever depends on the usage! Streets for cars are buildt becaus people buy and uuuse their cars. Bicycle infrastructure is ALLWAYS efficient, if it is used. So: the question is: Does your city NEED cycle-infrastructure? Do you understand what I mean? Sorry for my English!

Carry on working for the bike! 😉 You are on the “good side”…

To explore a different angle – what would $30MM buy in additional education about and enforcement of laws relevant to bicycle safety? This could be anything from adding bicycle safety topics to drivers’ education/testing, to a driver awareness campaign against right-hooking and dooring, to warnings/citations for blocking bike lanes, to warnings/citations for night riding witout lights, to assertive investigation/prosecution of car-bicycle accidents. Much attention is paid to building infrastructure for cycling, which is good, but the behavior of those in and around that infrastructure is also important.

What a great variation on the theme.

It’s so easy to guesstimate costs for some of these things, but the reality is that what seems easy to a lay person is usually far from it. These improvements typically have real complications due to interactions with private property, utilities, insurance requirements, other city or state codes, traffic control, etc.

Case in point. $30 million for 100 miles of sidewalk. That comes to $56/lineal foot of sidewalk. Perhaps you can purchase the concrete for that price, but who’s doing the excavation, paying the insurance, surveyor, inspecting the quality, etc? I’ve seen sidewalks done by homeowners and I’ve seen it done right by the professionals. you might get 5 years out of the homeowner sidewalk versus 50+ years out of the contractor’s sidewalk.

I suspect the rest of these numbers are oversimplistic and wildly inaccurate.

The punishing part of the CRC math is that we could be paying $27 million a year in debt payments on the bonds, EVERY YEAR for the next 30 years. That’s state money that won’t go to fund other projects that would be more economically productive.

9watts, if you are really going to compare apples to apples, you can’t compare walking to biking to other transportation modes unless you also compare what they are transporting.

The train example listed above makes this most obvious. Rail is expensive per mile, but once in place, the tonnage / mile / dollar is far less than highways (which is why you see shipping containers on rails).

Similarly, a highway mile doesn’t convey the same things as a bikeway mile. Somehow, goods and services need to be conveyed from ports to distribution centers to stores, warehouses, etc.

I think it’s pretty obvious that within an urban core, bike and pedestrian infrastructure are most efficient per dollar / person mile. Thing is, we don’t all live within urban cores, and if we do, we are even more reliant on an efficient interstate highway / train / air / shipping infrastructure to deliver goods and services.

I hear what you are saying, paul g, but I only partially agree.

Yes, trucks and trains haul a lot of merchandise around. More than I can on my bike trailer. But this is a matter of scale, not a categorical difference.

As for rural folk being more dependent on interstate commerce, well, that too shall pass. We currently truck so much around because fossil fuels have been cheap and getting cheaper for over a century. When that comes to an end we will discover that we didn’t need most of that stuff.

I think it is legitimate to compare walking and biking to those other modes, because one day we’ll find ourselves back without the cars and the trucks and the planes and it will be very different but it will still work. We’ll still take care of commerce, and there will be much less wear on the roads….