Part of NW Portland Week.

Portland’s “huge population boom” and “explosive growth” have driven such a painful housing shortage that it’s not uncommon these days to hear Portlanders wish the city would stop creating so many jobs.

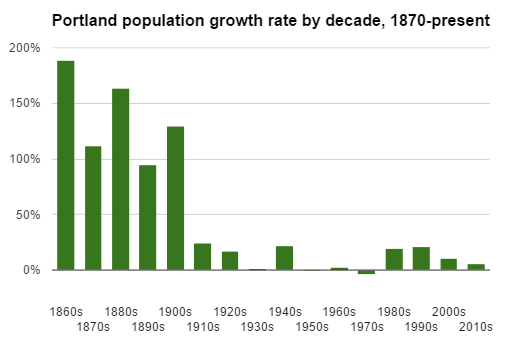

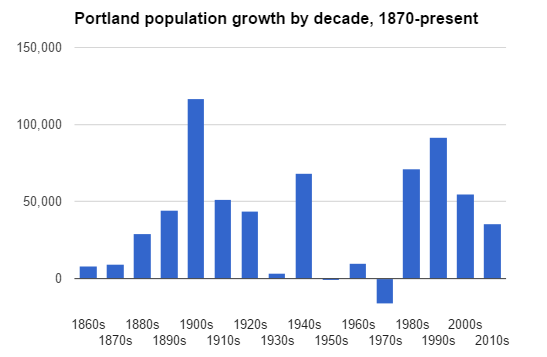

Since 2008, the city’s population growth rate has been about 9,000 net new residents per year, or 1.5 percent.

But when many of the buildings that continue to define northwest Portland were built, Portland’s population was growing by 7 percent every year for years on end. In the decade of the 1900s, the city that started at 90,000 residents added 11,679 new ones every year on average.

How could it happen? With so many migrants pouring into the aftermath of northwest Portland’s hugely successful Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in 1905, how could the city have possibly kept housing costs low enough to keep wages manageable for the host of new employers popping up? How did the city avoid cultural collapse?

Portland’s situation wasn’t unique. Seattle grew even faster in the same decade, and Los Angeles faster still. San Francisco’s similar boom came in the 1870s. For St. Louis it was the 1850s; for Philadelphia the 1860s; for Chicago the 1890s; for Detroit the 1910s.

How did cities survive population booms four or five times larger than Portland is going through today?

And why, somewhere around 1920, did U.S. cities never see population booms again — even in an age of deep geographic inequality that is watching smaller cities like Urbana, Illinois continue to shed jobs while some bigger ones, including Portland, add them hand over fist?

You can see the answer any time you ride a bike through northwest Portland. Growing cities built and built and built — because until 1920 or so, there were no laws that said you couldn’t.

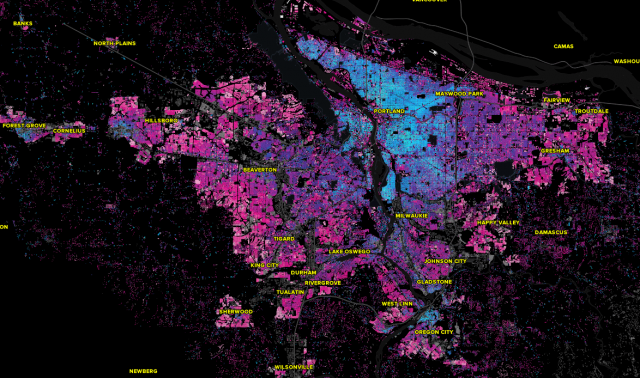

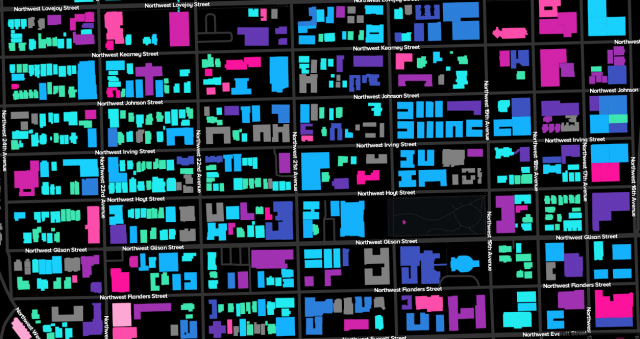

There’s no single image that explains Portland’s history at a glance better than Justin Palmer’s amazing Age of a City map, which color-codes almost every building on the Oregon side of the metro area by the decade of its construction.

(Image: Justin Palmer)

Zoom into northwest Portland and you can see the history, block by block, of how Portland survived its explosive 1900s:

Portland approved its first zoning laws in 1918 and expanded them by popular vote in 1924, limiting basic construction to four stories and maximum height to 15 stories; it was approximately the same year that local streetcar usage started its long decline. In 1945, lawns and driveways became mandatory in most of the city as minimum lot sizes were set at 5,000 square feet for single-family zones; in 1959, duplexes and internal home divisions were banned from single-family zones.

Nobody seems to be sure when mandatory garages and other minimum parking requirements arrived; Tony Jordan of Portland Shoupistas said city staff told him it was probably the 1950s.

Advertisement

None of this is to say that Portland’s boom decades were a golden age. The city had as many or more problems then. And it is not to say that market-priced housing can ever address the separate and huge problem of poverty. It can’t.

But the 1900s are proof positive that market-priced housing, if there’s enough of it, can be perfectly capable of controlling housing costs for those of us who aren’t currently poor.

And today, spending time in the neighborhoods Portlanders built in the 1900s, like much of northwest Portland, doesn’t just mean seeing buildings that were needed to prevent spiraling rents or enable job growth. It means enjoying yourself. It means spending time in a place that is quite nice.

Last year, former Metro councilor and former northwest Portlander Robert Liberty wrote a love letter to Nob Hill called “My Illegal Neighborhood.”

Typical city zoning makes it illegal to build or operate a warehouse or a light industrial use next to homes and a grocery store. The separation of industrial and commercial uses from residential uses was the very foundation of zoning a century ago.

It is illegal in most cities to build apartment buildings without providing one or more parking spaces for every apartment. The same would be true of grocery stores or office buildings. The neighborhood’s grocery store has fewer than 20 parking spaces.

The street in my old neighborhood does not meet more current design requirements, because it is considered inappropriate to design a street so that car cannot pass each other at any time or location. The street is 27 feet wide, curb to curb. That includes parallel parking on both sides, leaving a travel lane about 12 feet wide. That violates the standards for a local road recommended by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.

In most cities, you cannot operate a business out of your home if you have employees or customers arriving from other locations.

In too many places, it is effectively illegal to build subsidized housing for families of modest means. Even when it might be legal, local officials can interpret nebulous phrases like “preserve neighborhood character” or complex regulations in way that such housing is never approved.

A senior center, even though it is not a business, would be treated like a commercial use that cannot be allowed next to single family homes.

The elementary school would probably be illegal too because the school property would be too small to meet many states’ standards. The school is located on about 9.8 acres but many of those acres are occupied by a park open to the public at all times. The school, which has 685 students, would require a site of 11.85 acres in California, Texas and Connecticut, 15 acres in New Mexico and 18-20 acres in suburban Pennsylvania.

And then there is the absence of parking places; according to Virginia’s 2010 school design standards, the school should provide parking for all the staff, visitors and about a third of the students. (Apparently the legal driving age in Virginia is much younger than in Oregon.) …

Does that mean do away with all regulations? No. But it does mean that we need to stop assuming that everyone wants to, or can afford to, live in a big house on a big lot in a residential-only neighborhood. We shouldn’t be making it illegal to build the kind of neighborhoods, like mine, that are increasingly popular and in short supply.

Portland is in the middle of an election season in which no subject is hotter than the upward spiral of market-rate rents. The problem has the city in a constant roil. Policy wonks are scouring the planet for cities with tools that can prevent rapid population growth from becoming a disaster for market-rate housing.

Northwest Portlanders are lucky. The model everyone is searching for is their own history, and it’s standing right in front of them.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here. Our work is supported by subscribers. Please become one today..

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Right On! All the great things in this article were designed and built before the era of happy motoring. It is now time abandon the mass use of the automobile and the sprawl, pollution, traffic, carnage of vulnerable road users and climate change that come with it. The secrets we need to accomplish this are not found in the Techno future of Elion Musk or Bill Gates but in the buildings, transportation and landscape of that earlier time.

The past has great models for how to build cities, but “Techno future” ideas don’t have to be at odds with that. Of your two examples, Musk may ultimately be remembered more for batteries than for vehicles, but if not, at least city living could be improved if the vehicles that are present are quieter and less polluting. And computers are making it more possible (among other things) for people to work at home, a characteristic of much earlier urban life that was almost lost when zoning and other forces led to people living in one place in a city (or outside it) then commuting to another area to work.

If you want to reduce the number of cars and amounts of pavement, a great place to to start is to eliminate the need to commute, and computers can help accomplish that.

I don’t WANT to work at home.

Well, then your commute just got less crowded, if those who do want to work at home are able to.

The only thing I miss about working in an office is riding my bike to and from there five days a week.

I completely agree with you!

The impediments to working at home are not primarily technological or legal; they are social and organizational. I’ve done it with a very supportive boss, thought I would love it, but ended up going to the office nearly every day by the end of the first year. (My cousin has been more successful, and set up his home office at the bottom of a mountain; he skis between meetings. It’s all about the incentives!)

I agree completely. However, Portland’s rules could be tweaked pretty easily to allow more people to work at home without undue impacts to neighbors, so at least the people who have overcome the social and organizational impediments aren’t stopped by the zoning code.

I would contend that only a small minority of people who can worth from home would entertain clients there. There are certainly cases where that might be true, but I think in many cases you either don’t have clients, or you would want to look more professional than is possible with a room in your house as your office.

That said, I don’t object to changing the rules as you suggest.

I agree in general. But that’s today’s thinking as well. I remember biking and running to work in the 80s. Where I worked, it was considered a step up from unprofessional, and even that was only because I was young enough I could get away with it. Few workplaces now would frown on anyone commuting by bike. Working at home now is also far more mainstream than it was a few years ago. Meeting clients at a home office will (I hope) also become much more mainstream, and be seen as no less professional than meeting in a commercial building.

Like the zoning code in general, home occupation rules were written with the intent of prohibiting situations that were considered obviously bad–converting a house into a full-blown office or shop, with multiple employees and/or lots of customers. But in the process, lots of situations less intense than what were approved were also prohibited.

For instance, you can have one employee come in every day, all day. Or you can have 8 customers per day. But you can’t have zero customers and two employees, who each work at home themselves, come in say, every Tuesday, then work at home the rest of the week. You can’t even have one come in in Tuesday morning and another Tuesday afternoon, even if they’re gone the rest of the week.

You also can’t have one employee part-time, plus only one or two customers per week, because you’re allowed either an employee, or customers, but no combination of both, no matter how minor.

I know home occupations are one small part in the big picture, but they’re such a telling example of zoning’s obsession with separating uses that has been destroying cities over the last century.

The Immigration Act of 1924 was likely a major contributing factor to the lack of population booms after 1920. This act severely limited incoming migrants from any region outside the British Isles: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immigration_Act_of_1924

I know it’s not a comfortable subject, but we also need to look at population trends. They inform the scarcity of housing, too.

Old people are living longer (though not always in better health).

More young people are surviving to adulthood.

Job growth and living capacity have not expanded to match pace with these decades-long population trends.

While some pine for the good old days of pre-automobile-dependent neighborhood design, do those same people also want to go back to the days when 50 was considered old age and many more children did not live to adulthood? Nothing happens in a vacuum.

I wouldn’t mind returning to the days where we had public parks instead of yards, and raising children in an apartment complex without a yard wasn’t considered bad parenting. I’d also like to return to the days where allowing your 7-year-old child to roam the streets alone wouldn’t result in an arrest for child endangerment.

I’m not saying apartment life is bad! I grew up in apartments until I was 12 and we moved to Oregon. (Disclaimer: I was born in Queens NY, where MOST people lived in apartments in the 1960’s.)

I’m just saying that all sorts of social, biological and economic factors inform density, and that we need to remember that when those of us who favor urban density try to convinve our friends that it’s a good idea. They may be carrying baggage from other lifestyles that feel familiar to them, and that familiarity can be very hard to overcome.

On its own, density is neither good nor bad, but it definitely changes the way people live. Not everyone wants a heavily urban lifestyle, and that may be one reason so many push back when people suggest transforming their homes and neighborhoods into a dense urban form.

“allowing your 7-year-old child to roam the streets alone wouldn’t result in an arrest for child endangerment.”

I think that would be “child neglect”, rather than endangerment. You pretty much have to cook meth in the same room or point guns at them to be considered “endangerment”. But you can still get arrested if you leave one alone in a car for more than 7 minutes!

good point: actually it was even younger…47 years old if you were born in 1900

…as a white man.

These statistics ahould be treated with extreme caution. Average age of, say, 47 has almost everything to do with infant mortality and not a lot with how old people who survived to age 5 actually got. This is a very common mistake but no less problematic.

http://www.maxroser.com/gains-for-all-life-expectancy-by-age/

Yep. In 1845 this site give life expectancy at birth in the UK of 40. For a 1 year old it jumps to 47. For a 5 year old it’s already up to 55.

Are you implying a correlation?

I fail to see any connection between neighborhood design and longevity. Other than up until the WWI or even WWII, families took care of their own elderly members by having them move in or build a small place (ADU they call them now) in the backyard.

Most those building pictured are pretty much what we are building now – multistory, multiuse buildings. Before 1900’s this was a pretty standard design for most cities and towns. City hall, surrounded by a commercial multiuse core, then a circle of larger public and commercial facilities like the hardware store, grocery store, post office and schools, then it was surrounded by houses and downwind from the city was the main industrial section. Even most the big cities in the US of started with the same basic layout. It worked and was effective and convenient. As cities grew those multi-use blocks expanded and the neighborhoods moved out a little more.

Modern urban design really isn’t that modern, it simply noticed that designing for the automobile (which by the way kills over 100k US citizens a year if you include medical issues from the pollution of the automobile) doesn’t work, or at least doesn’t work for out best interest. And so basically while looking at the future, it’s basically gone back and is starting to pick up the pieces of what was going on nearly 100 years ago- trains, bikes, multiuse arterials – all straight from a very old playbook, the one that was developed naturally for and by humans hundreds of years before the automobile.

Actually average life expectancy in past eras was heavily influenced by infant mortality. If you lived past childhood, you could live to be 80-90, as two of the first three presidents of the USA did. There were plenty of septuagenarians on the streets of NW Portland in 1900.

In the last year I have gone from driving daily to only being in a car roughly once a week, if that. It is a bummer that my life expectancy has decreased so much because of it though…

And the Portland of that era also had several near by political competitors in planning (er I mean expansion / development) … the Albina, Kenton, East Portland etc…I assume if more restrictive development codes occurred in old Portland then business land owners would take their investment to the other Portland / Kenton / Albina. It seems interesting that Portland clamped down on these codes right after it successfully annexed these once independent areas … perhaps it was a strategy, as there may have been resistance to annexation if codes were deemed too “expensive” / “burdensome”.

Perhaps a PSU planning student can pull any existing building code materials from these ex-cities and compare them to Portland’s before and after 1920.

Joe Cortright did an excellent analysis of how the start of zoning codes in the 1920-30s restricted housing and affordability.

The images above are exactly the kind of neighborhood I want to live in. The places mandated by current zoning don’t interest me in the least. Unfortunately, I want a two-bedroom for our growing family and there isn’t one I can afford in NW Portland. Thanks a lot, zoning!

choose another quadrant.

I live in one of the buildings photographed for this article. It’s very close to downtown and most amenities. My commute is just a 1.2 mile bike ride. I support walkability and density in principle and in practice. NW is a great place to live and has far higher density than any other quadrant in Portland.

That said, I want to know how many of the many evangelists for a car-free lifestyle actually have given up their automobiles. Newsflash: Most of the people who live in my building do own cars and park them on the public street. The spaces are coveted and hotly contested, even though parking on the street is perilous because there are new break-ins almost every night. Couch Street between NW 19th and 14th is littered with shattered autoglass.

Living without a car, or with street parking only, blows. The reality is most people have cars. I think all the new construction should require resident parking to accommodate that reality. It’s not a genius feat of engineering to install an underground parking garage – you don’t even need a bigger building lot to do it, either. it just cuts into the developer’s already ample margins. If the developer has a problem with that, hell – charge an extra $150 a month. People will pay it. As it is, developers are foisting the externalities (private vehicles) onto the public by giving residents no option but the street. Articles like this simply enable this theft from the public.

As the 200 unit complexes start filling up in upper Northwest, you’re going to see more strife over this, and wish you had not harbored a fantasy that legislating away a parking requirement was going to solve the problem. Look at Division Street, etc. It’s a total nightmare for long-time residents there, from what I hear.

thank you for the forum. I look forward to responses, hopefully not all negative ones.

“Living without a car, or with street parking only, blows.”

You should try it (the living without a car part). You might be surprised how much you enjoy it.

Yep. Did it. Have you?

My point is not everyone is so lucky as i am to have a white collar job they can bike to work from inner NW Portland. This article idealizes a neighborhood to push an agenda, but the reality is most people can’t conform to the ideal espoused, even if the feudal lords wish that they could.

why not require parking in new buildings if it’s at no additional cost to the public? How many demographic studies have been done showing that millenials are actually eager to give up their cars versus merely tolerating the idea in principle? Or is this simply the agenda of the already wealthy and developers who are asking us to make sacrifices cloaked in green appeal?

I’m not opposed to density, biking, or streetcars. I’m opposed to the externality of private automobiles on the public street and removing options for the many. Look at a neighborhood that actually has no public parking: the Pearl. Condos there are selling g to Californians, for $1m in cash and they include private parking. The rich are not willing to accept this car-free ideal you espouse and the rest of us shouldn’t either.

For the past 19 years, yes.

I didn’t have a car for a few months when I was in the service. Every time I got off the ship I got to walk around with a great big bag of dirty laundry over my shoulder and I swore NEVER AGAIN. I’ve always owned a car ever since.

Go ahead and declare be car free a victory as you bum rides from your “friends”. I had one “friend” that bum a ride from me, critiqued my driving and took me 100 miles out of my way. Car free my ass. You get to bum mine. Car free hypocrites is what you are.

It’s clearly not for everyone.

I’ll note parenthetically, though, that the selfishness which you allude to and which can interfere with carpooling is I think the bigger problem here.

Here’s a freakonomics episode on the decline of carpooling.

Not my fault my city decided to build the roads for cars. I’m just trying to do what I can.

Wow Doug, that’s a lot of energy. Perhaps don’t think about it in absolutes: think about “car lite”. I have a friend here in Portland who uses a car a few times per year to take an animal to the vet, and we’ll share a car to get to remote events like Monster Cookie and Cycle Oregon.

Yeah, that isn’t 100% carfree. It’s also easier now to not “bum rides” with car2go, zipcar, getaround, etc.

Why do you choose to live in a building without parking? And why do you think others should be deprived of that choice by adding parking minimums (that don’t currently exist in NW)?

Car free NWer here. Can’t say I’ve missed it one bit. I love living in a building without inattentive drivers flying in and out of garages/parking lots. And it is SIGNIFICANTLY less expensive for me to use car2go/Uber/Lyft a few times a month, and to rent a car for day trips, than it is to just own and maintain a car, much less pay nearly $2000 a year for parking on top of that or have that extra cost built into my rent.

I bet that if your neighbors really sat down and looked at what their car costs them, and compared it to occasional rentals/carsharing like I do, many of them might find they would save money and be happier/less stressed just selling their vehicles and pocketing the cash difference.

My brother moved to San Francisco, and eventually came to this conclusion as well. He rarely drove even when he had a car, and it was very expensive to own one. The funny thing is he keeps telling me what a pain it is to not have a car, how he always feels that he’s mooching off his friends, and that it makes his social life awkward. He’s tried all the obvious solutions (there’s even a place to rent cars near his apartment). Is he better off without a car? He’s very much on the fence about that. Is the world better off now that he’s carless? I think it’s a wash. So why the push for people to go carless?

“So why the push for people to go carless?”

Is that a rhetorical question? 🙂

There’s an externality associated with U/L car hire services. They’ve gone screaming into the lead as the worst drivers on the road. They’re paid (poorly) on commission, they have no medallion number, and, lacking local knowledge, their eyes and hands are on a GPS half the time. Some drift around like tourists and some are more aggressive than a cop on a quiet call. Last week I actually got shoaled by an Uber driver on SW Taylor. In 17 years working as a messenger that is a first. Yes I did catch up and whisper in that person’s ear.

f*** u***

I would also add that there is something coming that will help your neighbors. The planning commission recommended allowing churches, hospitals, businesses, etc. to “share” their parking and rent it out to residents/visitors. This will help people such as your neighbors with alternatives to on-street parking without requiring people in new buildings to pay for expensive new parking garages. Also, restricting the number, and increasing the cost, of on-street permits would help bring supply in line with demand, and make it more likely that people will choose to live in the neighborhood without a car and take advantage of those other options 🙂

I don’t disagree with the change, but it is worth noting that one reason for the rule in the first place was to discourage people from operating a parking business under the guise of just renting out a few extra spots, and discourage the development of more parking lots.

people parking their cars in public spots are stealing form the public?

this position only makes sense if people living in apartment buildings are not the “public”. (sadly, this sentiment is not uncommon in portland.)

I live in mid-southeast without a car and I get around just fine.

Portland’s zoning code is one of the biggest impediments to designing and building good new buildings, and many of the problematic regulations are fairly new.

Houston has very few zoning laws, so there is some precedent for forgoing these problematic rules.

Houston’s on the other end of the spectrum. But when zoning staff here is looking at a proposal, and saying this is exactly the kind of development we’d like to see in Portland, but unfortunately our code doesn’t allow it, that’s a pretty good sign the code could be improved.

Houston doesn’t have a document called the “Houston Zoning Code”, but it has a lot of development regulations that are commonly found in the zoning codes of other cities. These include minimum lot sizes for residential development and minimum parking requirements. As example, the minimum parking ratio in Houston is 1.333 spaces for every one bedroom apartment. There are few (if any?) buildings in Portland being built with that much parking.

Excellent article. It’s similar to a mini-rant that I have- NW Portland is the place we can (and should) add population. We planned on doing this for the last 15+ years, very little demolition is needed, 6-story apartment buildings don’t take away from the “character”.

The 1900-era and 1920s-era apartments are great. Generally they are simple with very little actual design touches. That’s okay. The buildings that are going in are similar- mostly large boxes for humans with a nod towards design. Apartments and condos aren’t meant to be monuments, after all.

You should look at the zoning and height limits planned for the Conway district. An area with no historical context or nearby residential population.

And then proceed to get angry.

I just spent 10 mins looking for the proposed/planned zoning and can’t find it, just the current EX.

Found the master plan. 67-87 feet, 3:1 FAR. So?

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

3:1 FAR is way below what should be built there if we’re serious about encouraging higher population in the city center. We were handed a blank slate and then proceeded to completely squander it.

Aha- I thought you were arguing the other side- that it was “too much”.

Agree, it’s not terribly dense.

Even worse, min and max parking is 1:1 for apartments. That’s a sad mandatory.(edit: I’m wrong on this, “minimum: none”)

Hey, when can (why don’t) we get the ability to edit our comments?! 🙂

“NW Portland is the place we can (and should) add population.”

You mean because (you believe) population growth is inevitable?

Because I think we should be careful about suggesting that sort of thing without any qualifications. Many people may like NW Portland right now, but add another 20,000 people or 100,000 in short order, and it may not be so delightful to those people. Carrying capacity comes in lots of guises.

Yes, I believe population growth is inevitable- or real estate demand gets high enough to price people out.

Population will grow until prices reach their “equilibrium” where there are an equal number of people coming as leaving.

right. which is worse (to perhaps 90% of people) than being concerned about/against population growth.

I don’t think it’s a choice, but an inevitability; as long as we’re the cheapest city on the west coast, people will come. Until we aren’t. It’s foolish to think we can just build more buildings and the problem will go away.

building additional market rate housing is only one tool. there is a wide array of tools that can enhance housing equity. some of these include social housing, land trusts, inclusionary zoning, rent regulation, legal protections for tenants. many democratic nations have used these very tools to make their cities more affordable and inclusive.

i also wonder how you reconcile your position with the recent decline in rental rates in seattle:

http://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/morning_call/2015/12/report-finds-alarming-deterioration-of-seattle.html

Population growth = (births – deaths) + (immigration – emigration)

There’s also a factory in NW that produces additional people. A friend told me they’ve been working extra shifts lately.

You mean because (you believe) having more people would make a place undesirable? Many people like the beauty and pristine nature of Oregon farmland right now, but start enacting anti-growth policies like the ones you continually espouse, and it may not be so delightful to those people when that farmland turns into subdivisions.

“You mean because (you believe) having more people would make a place undesirable?”

Find me a group of people, a neighborhood, a city, a region that prefers rapid growth over stability (developers and real estate speculators are excluded). Rapid growth invariably creates lots of losers, stress, disruption, and a few big winners.

This is exactly the problem, I think. It’s not so much the magnitude of the growth, but it’s speed that is causing many of the issues.

I don’t understand how “growth” turned into “rapid growth” in this conversation.

The perception by many people I interact with is that the growth we’re experiencing is more rapid than would be desirable. I don’t think this is so much about precise historical comparisons (did we ever grow faster than today?) but about what people feel is OK.

I think it worth keeping all this in mind when we assert or demand or acquiesce to certain rates of growth as if this were the natural order of things, as if everyone were on board.

Also, boom-style growth is much different when you are a new city with a small population than when you are a mature city.

an excellent point.

I agree that it’s very different – it’s a much bigger change to double or almost triple your population as a new city than to add 5-10% in a mature city. The difference is that where we’re adding population now is infill with lots of neighbors who can easily organize politically, whereas back then it was greenfield development with many fewer neighbors (but the life experience of pretty much everyone in the city was drastically altered by having the close-by outlying fields and forests developed, they were just a more diffuse and therefore less politically powerful force.)

It’s not that neighbors can now organize, it’s that they now want to. I think there is a much stronger sense of wanting to slow the pace of change than there was when the emphasis was attracting enough people to build an economy. What established residents want is different now.

So, the size that Portland is at now is the natural democratically-determined size for a city, the size at which established residents stop approving growth and start wanting things to stay the same? How convenient that we happen to be at this wondrous natural size. How sad for the hundreds of cities that grew larger than us. I guess their growth was in every case railroaded through by outsiders against the desires of their established residents.

I don’t think I said any of that. I think I said that there are many people who don’t want to see their neighborhood transformed into something completely different than it is. I think that’s true even for many of the commenters on BikePortland.

I’m just trying to figure out – what do you think is different now versus decades ago? Are we big enough and rich enough that the economic benefits of population growth don’t play as well? If so, why did some other cities grow to be so much bigger and denser?

Or, has the growth narrative lost its power because the people vs. nature settling the frontier mindset is obsolete and largely discredited? Has there been a shift in political power from rich multifamily developers to mostly upper-middle-class inner-neighborhood single-family homeowners due to party machines becoming less powerful and the upper-middle-class getting bigger? Does growth have more downsides for neighbors now because so many people get around by car? Personally, I think all of those things make some sense – and more sense than the theory that when Portland was small, people were OK with growth because the city was small (there are plenty of small cities now fighting growth tooth and nail). What do you think?

“Are we big enough and rich enough that the economic benefits of population growth don’t play as well?”

Carrying capacity is measurable, though we can of course argue endlessly about the metrics. The point though is that just because we’re arguing about this in 2016 doesn’t mean others didn’t try in 1974 or 1998, and in any case the sustainable ratio of people to square mile or acre feet of fresh water or inch of top soil was probably a long time ago.

Alex- totally agree- i think that the key now is growth in the past 5-10 years is directed towards infill to Portland proper instead of development being sent to outlying suburbs. I think Portland proper has been insulated from the infill concerns until the last decade or so. Living in Milwaukie/Oak Grove since the 80’s alot of infill occurred in the 1990s and 2000 and really changed the character of the area and continues to do so. (Cramming townhouses next to 1920s houses,flag lots, creating no sense of continuity, etc). I think the local neighborhood populations were expected to grin and bear it for the good of the region to reduce sprawl. Unfortunately we did not have the political power to confront. I’m hoping that Portlanders who have more political power can convince planners how disruptive some infill can be. Infill does change the character or a neighborhood. Hopefully it can be planned in a way to create a positive outcome for both new and old neighbors.

population growth in portland is inevitable as people from areas that are increasingly inhospitable move here. climate refugees are coming (and i welcome them). population growth in the usa is in long-term decline and would be negative or zero without immigration.

urbanism is one of the best predictors of decreased fecundity. those who are concerned about population growth should advocate for dense urban cities and the income redistribution that makes them possible in the developing world.

“those who are concerned about population growth should advocate for dense urban cities and the income redistribution that makes [urbanism] possible in the developing world.”

dense urban cities are fine, but they are not an answer to the problem of too many people crammed into a now over-full planet. Density is merely a ratio not a cap or an invitation to grapple with limits.

The developing world is already home to some of the world’s biggest cities.

and population growth in those cities is lower than in rural areas.

Yes, there is no question that urban living lower birthrates.

http://pubs.iied.org/10653IIED.html

I do not personally think growth should be inevitable.

I do, however, think that the city sees it as both inevitable and desirable.

Pointing out that growth for the sake of growth rarely benefits current residents is worth saying every now and then, but I don’t think anyone cares, especially not after everyone finishes throwing around their crisis language.

The question still stands to all who are espousing a no-population-growth point of view. What is the optimal size of the city? If you say “what it is right now”, why is this optimal, not what it was in, say, 1983?

Did anyone actually say this, Ted, or is this another straw man?

Liberty’s comments are great, especially his mentioning how home occupations have been almost outlawed. They have huge positive impacts for cities. Yet even progressive Portland has horribly strict regulations. You can have one employee, or customers, but not both. A single person who works at home, sees a couple customers a week, and has a part-time employee, all happening only during the day while his neighbors are at work, is illegal here.

Want to solve the housing crisis? Eliminate all single family zoning. Make all of Portland inside I-205 R1/CM1 or denser.

Jeg – is that you? 😉

So what happens when developers build enough housing to completely house the top end of the market? Single family houses will then be selling for $1M or more (because there will be more people clamoring for fewer houses). Will developers start buying those remaining $1M houses to build apartments for the lower end of the market? Or will they seek more profitable opportunities elsewhere? What we’ll have is an even more stratified housing market, with plenty of choice on the top end, and the most affordable buildings used as development fodder.

I don’t think IZ is the answer, as we need a lot more relatively affordable units than high end ones.

Yup, that’s exactly what will happen – and middle-class people will choose to live further out or live in multifamily buildings. It’s also exactly what’s happening now, except multifamily buildings are less of an option because they’re so scarce that the prices for units in them are artificially high.

Who will build the less expensive units that we need? As land becomes more expensive (a process well underway), will developers try to go more downmarket than they’re willing to today?

Yes developers will go downmarket. The absolute price of land is less relevant when you stop requiring people live in low density housing. Apartments allow mid income people to pool together to outbid the wealthy for land that can be used for housing. Prohibiting that is why developers don’t go downmarket.

If this were legal, they would. Currently, exclusionary zoning subsidizes the demolition of shared housing and the construction of million dollar mcamansions.

No one is going to build affordable units on a $1M lot in the middle of Richmond. It’s not a question of what is legal, but what is economically sane.

Why not? That land cost spread over 20 units is $50,000 per unit, which is not crazy. Spread over 50 units and it’s $20,000 per unit, which is even more reasonable. Yes, those densities only make sense right by centers and corridors – but there are plenty of single-family houses right near lively centers. E.g. The single-family house in Hollywood that is being replaced by 50 dorm-style housing units.

The context of the comment was Adam’s rezone everything, rebuild everything. But even now, when land prices are much lower than they will be, we’re not seeing developers racing to build affordable housing, even though there is a strong market demand for it.

What rezoning was done under the Adams administration?

Lower-cost market-rate housing comes from older buildings when enough new supply is being created to satisfy the high end. If you’re looking for new construction to have low rents at the outset, that needs government intervention (like official Affordable Housing which would need much stronger policy and much more public money to house a large portion of our low-income population).

So our affordable housing crisis will be solved in 30 years, maybe sooner if the construction is as shoddy as people say!

Much of our affordable rental stock was built as such. Most of those units were never high end.

Yes, unfortunately, it will probably take at least a decade of building, and possibly two or three – IF we actually allow high densities which we’re not planning to now – to remedy six decades of intense restrictions on density. It’s quite unfortunate, but problems long in the making are seldom fixed quickly. This probably applies to bike infrastructure, too, sadly.

Or move to Flint…plenty of housing. If you want a big, ugly city with awful public schools keep charging, well, if 11 1/2 mph is charging. NW will be a nightmare soon.

Actually, one sufficiently tall tower could provide all the housing we need.

If it’s too tall and in the wrong place, people living up in the hills will squawk. Remember that there’s been a height ceiling in effect for a long time, partly to protect the view the folks up in the hills paid extra for.

..::tongue firmly planted in cheek::..

I would actually suggest building it on a hill. The views from the top would be killer.

Great article. I live in one of the buildings built following the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition boom, and love it. People on BikePortland often idealize Copenhagen and Amsterdam, and there is no part of Portland that comes closer to the built form of those cities that Northwest does. As someone who grew up in Europe it’s one of the reasons I choose to live in this part of the city.

Enjoying the review of my late 80’s turf, but a few things to be noted:

At the same time SE was fighting off the Mt Hood Freeway, NW was fighting off I-505. In fact ODOT had begun to buy and tear down houses between Thurman and Vaughn all the way up to NW 30th. Hence all the newer stuff. And the I-405 Mitigation Fund was created after a long struggle.

Around the same time, NWDA was organized to resist the expansion of Good Sam Hospital which was removing housing…vacant lots still remain! St. Vincent moved out of NW, taking all its jobs to the suburbs, so there is something to be said for keeping Good Sam where it is.

Prior to that in the 60’s, PDC was planning a large “urban renewal” area north of Savior that would have converted housing to industrial land.

Then in the late 80’s it was Save the Good Old Houses.

So a lot of community struggle helped to retain what was built in the earlier days…for better or worse.

Some of my landmarks from the 50’s and 60’s that are long gone: Montgomery Wards, Forestry Building, Mazamas, Roses, Henry Thiele, Esquire Theatre, Norm Thompson’s. Happily the Neighborhood House, the Balch Creek Trail and a lot of fine old architecture hang on and NW is booming! The only thing worse is stagnation or is it?

“The only thing worse is stagnation or is it?”

You’ve suggested that here before. I don’t know. What do you think? What does stagnation even mean, practically?

Or what about the less pejorative stability? Our obsession with growth even interferes with our language. We can no longer conceive/allow nongrowth to be ok – it has to be framed as an inadequacy.

Leigh Phillips wrote “Austerity Ecology & the Collapse-Porn Addicts: A Defence Of Growth, Progress, Industry And Stuff” that is meant as a rebuttal against no-growth/austerity camps on the left and the right. She says “we happen to have an economic system that fetishises GDP growth above all else”.

The general thesis of her book:

Ah, but you were talking about population, not economic growth, right? I’m not sure you can fully separate population from economy. In any case, the US has grown by over 4% in the past 5 years. There’s only one state with negative growth and it was very slight.

“but you were talking about population, not economic growth, right?”

I’ve always tried, in my comments here, to suggest that we should keep track of both population and economic growth and stop incentivizing either.

That Leigh Phillips piece is frightfully full of straw men.

If her book is all straw men, do you have fullly-formed arguments against growth to share?

Well since we’re in Portland I tend to start here:

http://agoregon.org/page28.htm

http://agoregon.org/files/Endless%20Growth%20or%20the%20End%20of%20Growth.pdf

Why is our current population at the perfect number? Why don’t we return to the size at 1950, or 2000, or 1992?

“Why is our current population at the perfect number? ”

The perfect number from my perspective has to do with carrying capacity, something we here and in most of the rest of the country prefer not to think about. There is such a thing as too much. We’re very good at pushing the limits, at pretending constraints don’t apply to us, that we’ll just figure it out through ingenuity, building up, nanotechnology, or big batteries, but food and water and clean air are no longer free, and wherever you look we’re scraping the bottom of the barrel. I never said today’s size is optimal, and I doubt that Andy Kerr did either (in 2000). But we know what today’s population feels like, and if you’re in overshoot reining it in might sound more plausible than suggesting that, in fact, populations in 1890 or 1980 were actually closer to the long term carrying capacity of our region.

i do not understand why you are concerned about population growth in the usa when it is actually decreasing minus immigration. i personally am very concerned about population growth (and it’s impact on our environment) and this is why i give $600 each year to population services international. the issue in the usa is not population growth per se; but rather, the destructiveness of the standard american lifestyle.

“i do not understand why you are concerned about population growth in the usa when it is actually decreasing minus immigration.”

My weight is actually decreasing too, minus desserts.

As I’ve tried to suggest here in the past, I am concerned with local growth and the extent to which our tax dollars are spent to incentivize and reward it when this growth generates real losers in our midst. Abstract ratios for the US as a whole don’t mean much to me since I don’t live in that average place but in the very real, and very much swelling, place we call Portland. I don’t know what the ideal or optimum or sustainable population is, but I do know that if we keep kicking this can down the road because it is easier to talk about other things we’ll be sorry.

You fool! Of course he has an argument! Just like you should never start a land war in Asia, you should never start a war of citations with 9watts! We’re doomed.

🙂

In many ways, we already have technological progress that runs counter to trends of physical growth. How many of us still have big stereos, CD collections, take photos on film, etc.? Many of our physical possessions are becoming digital, which can grow almost without bound while decreasing the amount of stuff we have. Technological advance is not precluded by a low-growth economy, nor are advances in knowledge and science. In fact, I would posit that a sustainable low-growth economy is only possible with continuous progress in technology. That is not the same as a static economy.

I agree with most of what you just wrote, except this:

“we already have technological progress that runs counter to trends of physical growth.”

This is a common fallacy, to equate miniaturization and Moore’s law with decreases in physical throughput. Most of the devices we use today didn’t exist a generation ago, and the functions they perform are also new; they didn’t (for the most part) displace other, prior, more materially intensive analogues but tend to complement them. If you look at material stocks that are dug up, processed, transported, etc. per capita I doubt we see much of a decline. But if you know of a statistic that shows this I’d be curious to learn otherwise.

And now they just have shorter lives and wind up in rivers in India…

Also product life—a key dimension of material throughput—has declined immensely thanks to widespread computerization and the obsolescence that accompanies it. So whereas we once had a phone (one per household) that lasted twenty-forty years, now we have one (?) per person that has far more rare metals in it and its peripheral gadgets, and is replaced on average every 3(?) years?

My computer, currently held together with blue painters tape, says otherwise. 🙂

As a counter point, most computer manufacturers have stepped away from making more powerful machines and are now making more efficient ones. This suggests that the need to upgrade to the latest tech is slowing, and as more of our digital life migrates to central servers (Google Docs, for example), the less your individual machine matters. All you need is a way to get online, and last year’s machine will do that just fine.

I think we’re already nearing the end of the philosophy that computers need to be upgraded every 3 years, and we’ll see more of an emphasis on build quality (see Apple) and more durable products.

Cars are also becoming longer lived and more durable, though appliances seem to be going the other way. There are lots of counter points to my examples, but I see my consumption of physical goods dropping every year, replaced by digital ones. I may not be typical, but nor am I completely atypical.

“as more of our digital life migrates to central servers (Google Docs, for example), the less your individual machine matters.”

True, but more and more servers are being used to analyze your traffic to create their own views of your digital twin. And then there’s the energy powering those servers and the equipment to move all those packets…

Oh, and I dig the blue painters tape!

RE: cars, I had nearly 400K on my `90 Acura Integra when my friend totaled it; I’m hoping to have as many timing belt changes on my 2011 TSX!

There are definite downsides to current digital tends, without a doubt…

Youll see more emphasis on monthly subscriptions to everything no matter how much they’re actually used. This is sold as progress. Ypu pay, you play, no quarter. Nice clean and rational.

What a drag though.

Ironically, this is exactly my thoughts in regards to People’s Co-op — they keep talking about growth, but really, is that the objective?

Great comment! I remember those struggles… and all the Reedies renting highway department owned houses along Clinton Street. It is interesting to examine the surges. In 1924 there was the Hawthorne Bridge (built 1910), Steel Bridge (1912) and Broadway Bridge (1913). Before that, no bridges at all. The growth brought us Ross island (1926), Sellwood ((1925) and St Johns (1931). Then the great depression came to a new city that was no longer Portland and East Portland. The riffraff from the east were brought into the fold. Then, when WWII began and brought the boom, it was a whole new ballgame. After the war (and the Vanport flood) there was a desperate housing situation. “Housing for our boys!” was the cry. That is when they demolished virtually all of the grand estates downtown and built awful housing for the masses, which, too, have been long-since demolished.

The awful decision-making of the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s did not pivot until we elected a young pedophile as mayor in 1972. I believe that everything that made Portland the fine example of a city that it (still) is today was inspired and set in motion by Neil Goldshmidt. We have had white noise for leadership in this city ever since.

I was born in Portland in 1955. I went into business and got my contractors license in 1978. In the early 80’s I would go into the City Hall first-floor building permit counter where I could get everything I needed to finalize a permit. While at the counter the mayor and council members would walk by on their way to council meetings so I would finish my business and go watch.

The charts above illustrate that the city has grown by only about 240,000 since 1940. For the most part, the city was entirely built out by the time I was standing at that counter. It all got accomplished from that squatty little building on Fourth Ave. There was no Portland Building, nor were there the million square feet of office space the city stocks with individuals on their way to meetings.

The City That Works, like any government entity, is an unintelligent organism with a system design geared to feed itself. The vast majority of its energy and focus is inward. It cannot be remodeled. We either live with it as it is or perform a gut-rehab.

Awesome comment, and so many of us have mentioned time and again that systemic drive for “growth” that fuels those entities (and us, really, whether we like to admit it or not).

Yes, city government, like many governments, is a bloated, ineffective, wasteful, organism that is very harmful to those who pay the taxes to support it. But the voters, most likely because they’ve been dumbed down and brain-washed in public screwels, are only concerned about voting for more PC stuff like diversity is good at any cost, gay rights trampling the rights of everyone else, allowing unlimited immigration, allowing illegals to have drivers licenses so they can vote, lying by saying minorities can’t vote because they can’t get an ID, motor voter registration to get more liberals to vote who otherwise would be too lazy to register to vote (and have no business voting), and on and on and on and on. Then, you end up with bankrupt cities that are cesspools of crime and decay and the people just can’t figure out why it happened. It’d be funny if it weren’t real life.

Hey, when can (why don’t) we get the ability to edit our comments?! 🙂

didn’t nest under Ted Timmons strikethrough comment.

The logical conclusion to the urban growth boundary is to roll back zoning to 1905 minus light and heavy indistrial.

You’re right. It was built a century ago at the edge of the city on clear-cut land.

That’s still happening today.

Joe Weston built tons of low-end rentals throughout the city.

And many of them would be illegal under current exclusionary zoning.

Yes, but they are legal now. Besides, that era is over; no one is going to build affordable housing in Richmond. Land is too expensive.

A Facebook friend of mine told me a story he’d heard in a Portland area coffee shop the other day. The story gies that we are now adding 1,000 new residents every week, mostly from the SF Bay area, central CA (mostly Hwy. 99 corridor between Sacranento and Bakersfield), and Texas.

No wonder rents in this town are blowing thru the roof. A condo in my Mother’s building recently sold for half a million bucks.

I find the early growth rate to be very interesting and different from now. In 1850’s some of my ancestors arrived by wagon train or in the Military without a family. Then as the years went by they produced large families of 7 and even 11 children. These Children married and also had large families. So, in a single house you would have 10+ people living there. Sort of a locally developed population explosion.

I’ve seen a diary entry that suggested housing was very difficult to find. As upon arrival to Portland in the Fall of 1850 finding a Shack on a Mud street was considered lucky. The real fear was survival from cold weather.

I came here in 1992. Myself and other 20 somethings could afford to rent a nice house with a porch and a yard off of part time work. So we had time to do art and work on bikes and stuff. The dream of the 90s.

Nowadays I go out and hear quite a bit of people talking about how their rent is going up and they can’t find anywhere to live. The 20 somethings have decided to live elsewhere ’cause they can’t afford to live in Portland, and they see it as a dumb yuppie town anyway.

It’s a damn shame. My point is, the price of living in Portland is becoming prohibitive for young and working class people, any way you look at it, more than ever before.

I came here (to Earth) in 1958. When I substitute the words on Earth for in Portland in your comment it rings true.

Take care

Here is an idea to slow down parking problems and traffic when faced with an influx of new residents. Lets require ( as a state) that all new residents give up their original drivers licenses within 30 days of moving, then create a mandatory 5 year waiting period to get a new Oregon drivers license. If this is publicized in advance it will insure we get the kind of residents that will make Portland a better place, and it will give people a chance to experience a car free lifestyle before they go back to their old ways.

The other part of this story of course is the adoption of Statewide LU planning in 1970s. Statewide Planning actually liberalized a lot of zoning laws by requiring that local government development codes to provide clear and objective standards (paths) for new development. This and other provisions requiring and encouraging efficient use of land inside UGBs was a modest strike against provincial NYMBISM and insider wheeling dealing with respect to zoning and development laws.

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2016-04-18/growing-divergence-between-americas-most-and-least-affordable-cities

So tiresome, these articles. They’re all alike. All bemoan the fact that there are no good options (once you take unlimited population growth as given, which they of course never problematize). Expansive or expensive: very clever.

What is wrong with us that those who prefer things how they are or were are told to suck it up, are reminded that the absence of growth is not an item on the menu?

Sounds like you may be advocating for top-down control of some kind?

How’d that work out for the USSR? Not too well.

Sure, the choice to have fewer children is probably a wise one – we’re all free to make that choice – forcing that choice like was done in China has produced some problems.

I think the government needs an ever expanding economy to help absorb their ever expanding spending and debt levels. So, they push pro-growth policies.

And of course if you suggest limiting immigration or limiting H1B workers then you’re called a xenophobe or racist……..so, even people who advocate for lower growth rates, will advocate for more immigration which drives higher growth.

Some have suggested in comments above that the US population isn’t growing except for immigration. If that is so, then we must have an order of magnitude too many immigrants. Some relief in this area could be gained if Intel were forced to lay off all their H1Bs and they had to return to their original country – today Intel announced they’d be laying off 12,000 people world wide. For each H1B that is forced to leave, a home will open up for a US citizen. But I suppose it isn’t PC to want to help US citizens is it? US corporations: destroying middle class America one H1B at a time.

Population is exploding at least in the western US. All the roads are completely saturated with cars. Doesn’t matter where you go, it’s pretty much the same. New homes and businesses popping up all over. You can hardly find any place to get away from people. All the trailheads are overrun with hikers, etc……….. Lots of anecdotal evidence that the population is exploding. I would not believe government stats on population – probably many illegals not on any census.

Plenty of empty desert and mountain land in the US, but usually no water there, or too much snow in the winter, or no jobs, or it’s government land so you can’t live there, etc, etc.

A city’s boundary situation can skew these types of statistics tremendously. One city may have a small area, surrounded by huge amounts of population outside the limits. Another may have a large area within the city limits that encompasses much of the population of the entire metro area.

Portland is almost the same population of Seattle, but the metro area is much smaller. Both have separate cities near them (Beaverton, Vancouver, Bellevue) that are probably no further from their cores than are areas within the city limits of places like Houston that have much larger areas. Many of the “expansive” cities on that chart look like ones whose topography allows them to expand to become huge in land area, whereas the “expensive” ones are the opposite. If you drew a small circle around their cores (say a circle the size of the land area of Seattle, Portland, of several of the “expensive” cities, they might be just as “expensive”.

So the rankings are somewhat artificial to me.

You can check out that theory on Zillow.com.

Preliminary review of just 2 cities appears that they are in fact cheaper:

Houston, arranged by cheapest:

http://www.zillow.com/homes/for_sale/Houston-TX/fsba,fsbo,new_lt/house,condo,townhouse_type/39051_rid/50000-300000_price/178-1070_mp/any_days/pricea_sort/29.815029,-95.288544,29.715637,-95.472394_rect/12_zm/0_mmm/

Cincinnati, arranged by cheapest:

http://www.zillow.com/homes/for_sale/Cincinnati-OH/fsba,fsbo,new_lt/house,condo,townhouse_type/4099_rid/50000-300000_price/178-1070_mp/any_days/pricea_sort/39.152095,-84.419031,39.063249,-84.60288_rect/12_zm/0_mmm/