A major theme here at first-ever National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) Designing Cities conference is that reclaiming roadway space for people and designing streets for all users does not hurt the bottom line of businesses. In fact, as evidenced by the work of economist Joe Cortright and a report released this week by the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT), the opposite is true.

made possible by:

- Planet Bike

- Lancaster Engineering

- Readers like you!

At a panel titled Money Talks: Communicating economic benefits to build public support, Cortright presented the latest findings from his “Green Dividend” study. He was joined by Eric Lee, President of the company that performed the retail sales analysis of street projects that was released by the NYCDOT yesterday.

We first covered Cortright’s “Green Dividend” study back in 2007, when he revealed that because Portlanders drive four miles less than the national average, they save $1.1 billion dollars in transportation costs. Instead of being spent on gas and auto maintenance, that money stays in local pockets and helps boost local businesses.

his research on how a reduction in driving

can be an economic boost.

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

At the conference today, Cortright asked, “How much money would America save if we reduced driving by one mile per person, per day for an entire year?” Plugging the numbers into his equation, Cortright came up with $30 billion.

Cortright put the cost of driving into perspective.

- The average U.S. family spends $4,000 per year on gasoline (that’s $500 billion dollars per year for the U.S.)

- That’s about 6 percent of median family income

- Average household spending on gasoline doubled between 2000 and 2008 (according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- The cost of driving has tripled over the past decade

According to Cortright, a trend that could end this upward spiral of spending is that the number of miles Americans drive per year has fallen sharply in the past seven years. “2005 was ‘peak car’,” he said, comparing it to the more well-known peak oil phenomenon. We’ve all heard about this decline in driving, spurred in large part by the 25-34 year old demographic. Not only are young people driving fewer miles, they’re buying fewer cars and statistics show that many of them aren’t even bothering to get a license.

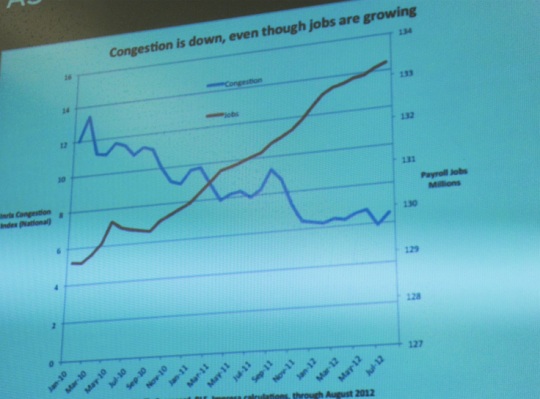

Despite these clear downward trends, many people in the transportation world refuse to believe it will last. “Isn’t this all due to the recession?” is a question Cortright said he frequently gets. The answer is simple: No.

Cortright shared a chart showing how vehicle miles traveled (VMT) changed after four previous recessions. All the VMT numbers in past recessions spiked way back up; but so far, since 2007, people are still not returning to previous driving levels. And even more surprisingly, Cortright says, congestion and VMT are going down as job growth is going up. “This is not a temporary artifact of the recession.”

Cortright says cities are the solution to supporting these trends because they allow people to drive less and keep more money in their pockets. Also, according to research from CEO for Cities, these “young and restless” 25-34 year olds are moving into close-in, urban neighborhoods at twice the rate they’re moving to suburbs.

There’s another big dividend that has come thanks to people driving less. Congestion across the country has declined by half nationally since 2010 (based on calculations by Impresa Consulting using the Inrix Traffic Scorecard). Cortright calls this a “surprising traffic bonus” due in large part to VMT reduction. “We spend a lot of money on capital projects trying to reduce congestion and travel times, but this reversal in the growth of VMT has contributed to significant congestion reduction.”

All of these numbers and trends prove to Cortright, that contrary to popular political attack lines, “Conservation is not bad for the economy. It produces real gains for households which they can spend other ways.”

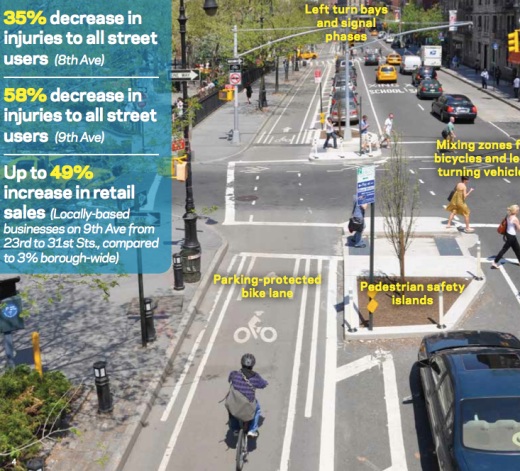

Putting a real-world exclamation point on Cortright’s analysis was Eric Lee, President of the management consulting company Bennett Midland and former policy advisory for New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg. Lee’s firm helped NYCDOT analyze how their recent transportation projects that have reclaimed traffic lanes for public plazas and dedicated space for bike and transit lanes, have impacted retail sales of adjacent businesses.

Using sales tax data, the analysis (contained in Measuring the Street: New Metrics for 21st Century Streets (PDF)) showed major retail sales increases adjacent to these street improvement projects.

- Retail sales went up 49% at businesses along the new protected bike lanes on 8th and 9th Avenues in Manhattan (compared to 3% borough-wide).

- At Union Square North, where NYCDOT expanded sidewalks, installed a protected bike lane and did other intersection improvements, commercial vacancies are down 49% (compared with to 5% borough-wide).

- A seating area installed in a former curb lane in Manhattan on Pearl Street resulted in a 14% increase in sales at adjacent businesses.

This panel discussion cemented a growing body of evidence that shows that giving people options to driving and transforming streets into places for people (not just cars) have significant — and positive — economic implications.

What if Portland transformed one of its downtown streets to create a public plaza, a protected bike lane, and so on? The NE Multnomah Main Street Project might be a good opportunity to do some of this type of analysis; but without sales tax, how can we measure the impact of transportation projects?

— This post is part of my ongoing New York City coverage. I’m here for a week to cover the NACTO Designing Cities conference and the city’s bike culture in general. This special reporting trip was made possible by Planet Bike, Lancaster Engineering, and by readers like you. Thank you! You can find all my New York City coverage here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

“Congestion across the country has declined by half nationally since 2010”

ODOT and City Council, which just approved $400 million for widening I-5 in the Rose Quarter, didn’t get that memo.

How will the Portland Business Alliance find a way to ignore this report?

What if Portland transformed one of its downtown streets to create a public plaza, a protected bike lane, and so on?

I don’t know what happened to that project to upgrade a major thorough-fare that was being discussed last year, but I’d think that Burnside would provide such a major opportunity. Burnside flows through a mix of business and residential districts from West to East city limits. If multiple modes were enabled throughout it’s length, it would become an amazing corridor. What would really take this over the top is if it could become totally traffic light free. One continuous flowing road with roundabouts or other means of redirecting traffic where needed. A lot of progress could happen through reallocation of existing pavement, but more could happen through special project funds where physcial changes are needed. Stormwater, carbon mitigation could be other considerations.

I’m on board with the thrust of this article, but one quibble: money spent on auto repairs is arguably retained in the local community, as is some percentage (I assume a small share) of spending on gasoline.

The data giving impact on retail sales is pretty eye-opening. I see this as pretty close to a zero-sum game though; aren’t those sales increases coming at the expense of other stores?

I love Joe and his work! Now if the DOTs would read it!

Portland missed a chance to do something significant when E Burnside got three lanes of traffic and no increase in ped space. What a missed opportunity that was. Likewise, PBOT and/or Mult. Co continues to insist on three lanes eastbound on the Burnside Bridge. What a promenade that would make with 20 foot bike/ped facilities on each side above the curb, if we went with just 4 lanes for motorized traffic instead of five.