Much has been written lately about a “bicycling renaissance” that has taken hold in America. At the NACTO Designing Cities conference here in New York City, I’ve had the opportunity to learn about the reality behind that renaissance and I’m happy to say that it’s real. Nowhere was that more apparent that at a panel discussion I attended today titled, 8-80 Bikeways: Designing protected bikeways and bicycle boulevards to accommodate a broader range of users. The session featured updates on bikeway development from four cities: Portland, Indianapolis, Chicago and New York City.

made possible by:

- Planet Bike

- Lancaster Engineering

- Readers like you!

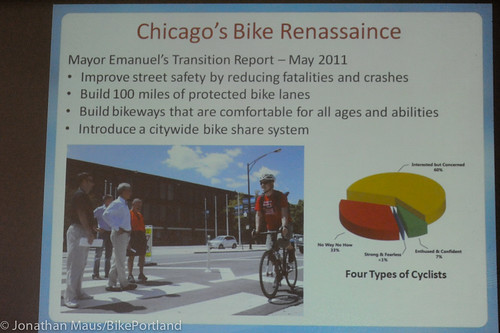

Most of you have heard about the need to attract people to bicycling that fall into the “interested but concerned” category. That phrase — which is now used by transportation officials across the country — was coined by the City of Portland’s Bike Coordinator Roger Geller back in 2006. It’s meant to describe the estimated 60% of the population that would like to try biking, but are too worried about safety and other issues to do it. Another way to think about that same concept is designing streets that appeal to the “8-80” demographic. As far as I know, that phrase was coined by the former City of Bogota Commissioner of Parks Gil Peñalosa (he’s now executive director of a non-profit by the same name). It’s used to describe the goal to have a network of bikeways where people young (8) and old (80) would feel safe navigating.

Martha Roskowski.

(Photo © J. Maus/BikePortland)

The session was moderated by Martha Roskowski, the director of the Green Lane Project. When it comes to attracting this broader range of people to bicycling, Roskowski believes there’s no substitute for high-quality, separated bikeways. Encouragement programs are important, she said, but they’re limited. “We can’t market out way into getting these people to ride.”

In his presentation, Geller acknowledged that even Portland (which was referred to by me as “that shining bike city upon a hill” by NYC DOT Commission Janette Sadik-Khan) has a lot of work to do. He shared the the highlights of Portland’s bike infrastructure; our 85 (and counting) on-street bike corrals, our neighborhood greenway network, and our protected bikeways like Cully Blvd, SW Moody, SW Broadway and SW Stark/Oak. But Geller knows what we lack is a connected network. “We need to build it even better,” he said, “We need to develop an entire network of protected bikeways.”

Geller pointed to the project currently being constructed on NE Multnomah St, where PBOT is re-striping the lanes and reallocating space to provide room for protected bike lanes. He called the plans, “A poor person’s cycle track,” meaning while we are re-working the space, the project isn’t building out the facilities to their full potential. At intersections with bus stops, for instance, PBOT has “mixing zones” where the bike lane ends and people will navigate with bus operators. “Ideally,” he said, “what we’d do is have a transit platform extended at the corner and buses would stop in traffic to board and deboard; but we can’t afford that, so we’re doing the mixing zone as a test to see how it works.”

“Are we an 8-80 city? No. We’re probably a 13-70 city; but we’re getting there.”

— Roger Geller, City of Portland Bike Coordinator

In his final analysis, Geller made an honest assessment: “Are we an 8-80 city? No. We’re probably a 13-70 city; but we’re getting there.” Geller said PBOT is in an “evolutionary process” and that “change is incremental.” He also told session attendees that he believes the barriers to doing more bold bike projects (perhaps like the ones New York City is doing) “are more political than practical.” “We don’t have the support from businesses or from the community that we need to re-purpose space from cars to bikes. And we don’t have support for the money we need to do it. Yes, bikes are a cheap date; but we do need some money.”

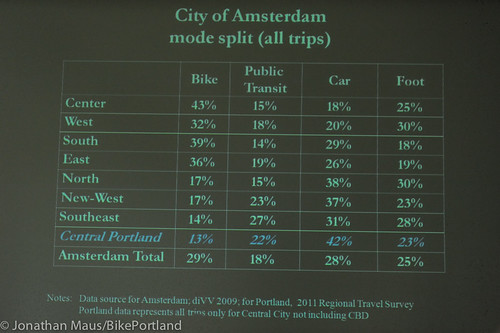

Geller shared the recent bike commuting numbers released just this week from the Metro Travel Survey. That survey revealed that 13% of Portlanders commute by bike within the central city/inner neighborhoods (excluded the central business district). He compared Portland’s numbers to bike commuting rates in Amsterdam. “That makes us an O.K., outer suburb of Amsterdam… So the best part of Portland is like the worst part of Amsterdam.”

While Portland enjoys an illustrious (and perhaps mythical) reputation for bicycling, Indianapolis is probably on the other end of the scale. But even there, the renaissance is real. Jamison Hutchins, the Bicycle and Pedestrian Coordinator for the City of Indianapolis, titled his presentation: From Zero to Hero. In 2007, they had less than one mile of bike lanes. But in the last four years — thanks in large part to support from their Mayor Greg Ballard — they’ve now got 67 miles of bike lanes. Their crown jewel, and perhaps one of the best examples of an 8-80 bikeway in the entire country, is the Indianapolis Cultural Trail.

The Cultural Trail is a $64 million (using a mix of private, local and stimulus grant funding), nine-mile path that loops through the city. It includes a separated cycle-track with signal priority and separate walking path. “Besides its functionality,” said Hutchins, “It’s just an amazing piece of awesomeness.” The path has spurred residential real estate development as well as a thriving new crop of businesses. It’s also provided momentum for other initiatives like the Indy Bike Hub parking facility, a newly passed complete streets policy, and a bike share system coming in 2013.

This year, for the first time ever, Hutchins said, the budget for the City of Indianapolis will include a dedicated revenue stream for bicycle improvements. According to to Hutchins, it was all possible because of Mayor Ballard. “He’s a Republican, and he understands bicycling from an economic development standpoint. He realizes we have to be able to compete with the Portlands and the Chicagos to attract the best talent so he’s given this top-down command to the engineers that it’s not all about cars anymore.”

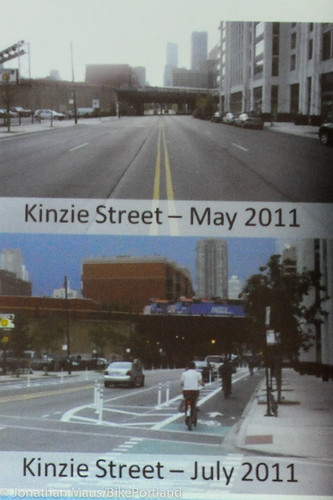

Speaking of Chicago, city officials there are building bikeways at a dizzying pace after a major proclamation by Mayor Rahm Emanuel in 2011 to build 100 miles of protected bike lanes by May 2015. Mike Amsden, the City of Chicago’s Bikeways Project Manager, said that effort has sparked a “bike renaissance” in Chicago over the past year.

“In one year and four months, we went from nothing, to having the second most protected bike lanes in the country.”

One key way they’ve been able to push bike projects through quickly is by leveraging the planned arrival of their bike share system. “We’ve got to have safe streets for people to ride on before bike share gets here. We’ve been able to use bike share as political leverage to take road space away from cars against the objections of some of our engineering staff.” Right now, their famous “loop” road has only a narrow, standard bike lane. But with bike share on the way, Amsden says they are moving forward with plans to build a two-way protected bike lane.

Moving to implement major bikeways so quickly been challenging. “It’s not easy moving fast,” Amsden said, “you piss off a lot of people when you do that.” He expressed regret that he and his staff simply don’t have time to do the necessary outreach to make projects successful from the outset. Another challenge is how to deal with street sweeping and snow removal once bollards and other separating features have been installed. They’ve been using a donated pick-up truck and Bobcats to do the plowing; but that’s not a feasible, long-term solution. Amsden said they’ve been testing a variety of sweepers and snow removers and he’d be happy to share what he knows (which is great, because I’ve heard PBOT engineers used the inability to sweep/maintain separated bikeways as an excuse to not implement them).

Perhaps the one American city coming closest to the 8-80 bikeways ideal is New York City. They’ve been getting so much praise in the bike world lately that it was actually a bit refreshing to hear the NYC DOT’s Director of Bicycle and Pedestrian Programs Josh Benson, share a project they got wrong. At least initially.

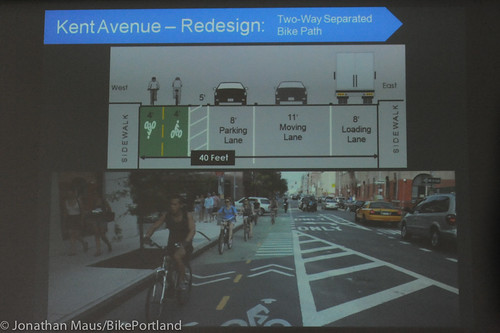

Benson shared a case study of their Kent Ave project that was completed in 2010. Kent Ave. was an industrial corridor along the East River waterfront with a typical, two lane cross-section with auto parking on both sides (like many Portland streets!). When the local community board (similar to our neighborhood associations) voted in support of a waterfront greenway path with no on-street auto parking, the NYCDOT went to work on the design. They implemented six-foot, curbside bike lanes. Unfortunately, the design didn’t work. Neighbors and business owners hated it: Speeding became a big problem due to the lack of parked cars to slow people down; industrial businesses couldn’t get curbside access for their trucks; many people parked and drove in the bike lane, and so on.

“So we redesigned it,” said Benson, “We used the feedback as an opportunity to make it a much better design and we got there by talking to everyone who cared about this street.”

The final design was much more creative. They turned it into a one-way street, installed a two-way buffered bike lane, and added a lane for parking and lane for loading. The result? A 200% increase in weekday bike traffic with a whopping 2,500 average bike trips on the weekend (1,700 on weekdays). And people liked it. “We turned it from our worst failure to one of our biggest successes.”

——

What can Portland learn from these cities? Where will we build our first 8-80 bikeway?

— This post is part of my ongoing New York City coverage. I’m here for a week to cover the NACTO Designing Cities conference and the city’s bike culture in general. This special reporting trip was made possible by Planet Bike, Lancaster Engineering, and by readers like you. Thank you! You can find all my New York City coverage here.

—-

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I saw the Indy Trail while visiting two summers ago. I so wish I had a bike at the time, not only because it was a really nice facility but because it was during a heat wave and I would have loved to have rolled casually in the breeze on a bike than hoof it the mile and back in the heat for the conference I was at.Seemed like a really nice facility.

“We don’t have the support from businesses or from the community that we need to re-purpose space from cars to bikes.”

What Portland can learn is that our political “leaders” need to step up to the plate of providing needed infrastructure changes despite whatever wrangling and hand wringing seems to go on over every last transit project. NYC and Bogota didn’t work wonders with their transportation grids by sitting back and listening to every moan and whine from every special interest that might be affected. They took bold action to make change, and that is what works. Asking to change our streetscape leaves people uneasy and suspicious; they are resistant to change from the outset.

Let’s face reality, Portland innovated some changes years ago that put bicycling in the spotlight but has done very little over the past 5-7 years. We passed a Bike Master Plan and set mode-split goals for 2030 that now sit around on a shelf and gather dust. Meanwhile other cities are taking real steps to improve conditions on the ground for non-drivers while we sit back and gape in wonder at how it is all possible.

Where is the separated cycle-track for Sandy, Burnside, Powell and/or Foster? Where is our dedicated route through the West Hills so that we can connect the west suburbs to the city? Where are our point to point north/south routes? For the bill of a $400 million highway overhaul, we could build an Indy Cultural style trail that spans the whole of Multnomah County. The sad reality? Our transportation planners are more concerned about making sure their jobs are stable than making our city a more bikable, walkable and livable place.

“NYC and Bogota didn’t work wonders with their transportation grids by sitting back and listening to every moan and whine from every special interest that might be affected. They took bold action to make change, and that is what works.”

Nice.

I’d add to this a way to differentiate between these competing voices. Some are desperate to hold onto holes in the air, studded tires, LOS, etc. If you scratch beneath the surface, these interests are trying to maintain the status quo/keep on using fossil fuels. Then there are the interests whose priorities coincide with livable, vibrant streets, and a future less dependent on fossil fuels (see all these great examples Jonathan’s discovering and profiling).

Human power is (once again) the future. The sooner we accept this the easier it is going to be on our budgets, not to mention making the places we live and pass through safer and more enjoyable.

I guess that implementing unconventional infrastructure changes takes more than bold action and money. It takes a certain amount of and type of support from the public, and not just from that part of the public that loves to bike.

Sure, while the idea of separated cycle tracks on some of Portland’s most heavily trafficked streets have a certain appeal and merit, how such changes would affect motor vehicle flow and carrying capacity are factors that have to be considered. Business believes motor vehicle accessibility is essential to their economic viability. Business isn’t the only essential support needed, but it’s a big part of the whole base of support needed.

People that work and need to commute to work are another big part. Since most of them travel by motor vehicle, any proposed changes that don’t appear to sustain motor vehicle street carrying capacity are likely to be looked upon with skepticism.

Also, ways in which Portland’s street grid close in, east and west of the Willamette is comparable to NYC Manhattan, relates to how viable some of NYC’s infrastructural changes might be for Portland.

I love the 8-80 concept. In certain places in Portland, it might be supported. Downtown’s Park Blocks are close to that now. Seems to me, Beaverton’s tri-sected Downtown has an opportunity to develop a pedestrian-bike throughway consistent with the 8-80 concept, but unconventional as that idea is, it seems very remote that many officials and planners would seriously consider it.

Let’s take the Bogota and NYC examples not as unconventional, but as the new convention. The world will necessarily become less dependent on oil and fossil fuel, and redesigning our cities’ transportation and freight networks around something other than the internal combustion engine will likewise be a necessity. Without leaders that can understand and envision this future who are willing to make real changes happen, we will fall behind quickly. At our current rate of progress, in five years Portland will be surpassed by many more U.S. cities in terms of its transportation network. Even the Republican mayor of Idianapolis recognizes the competitive advantage the new convention provides. Bloomberg and Sadik-Khan began NYC’s makeover to a lot of noise and political opposition, but they did it anyway, and now they have huge piles of data from cabs to prove they were right.

Business interests will generally fight the new convention to the death, if they can, because their bottom lines are based on predictability. They will get all up in a hizzy if they can’t calculate their next quarterly/annual profits because the city completely changed the way things work. But they will adapt because they have to and find that the new convention actually works better than the old one. Let’s stop with these compromise “experimental” designs that create more hazards than they cure and set our priorities straight: cars will no longer be the first consideration. By the time we have “public support” – because the public sees how well the new convention works everywhere else – it will be too late. We need a world class transportation grid, and we need it now.

It’s easy to see NYC and say that they can do those project because they have more money than us. But If Indianapolis can build a sweet cycle track through their downtown, so can Portland.

I find it quite disheartening that we still don’t have a really great non-automobile street downtown. One that mixes pedestrian, bicycle, and mass transit really well and doesn’t think twice about having automobile traffic or automobile parking.

Hello Burnside and Broadway. Or instead of Broadway, make the “bus mall” truly a non-auto mall.

We are getting there, ever so so so [SO PAINFULLY!] slowly. I’d suggest, nothing against Mr. Geller’s assessment, that it feels like we’re more of an 18-50 city.

Make the transit mall auto free except TriMet buses and EMS/fire.

It is an optimal confluence of dense pedestrian traffic rushing seemingly random directions to catch transfers and ground level retail.

There is no advantage to on street parking on the transit mall (is there any?) and with all the unpredictable pedestrian crossings there is no speed advantage to driving there.

There should be a great increase in pedestrian safely and bus operation safety not to mention bus schedule regularity should be greatly improved by removing auto traffic on the mall.

If any place in Portland should top the list for car free testbeds it should be the transit mall.

It was the hotels that pressed for parking on the transit mall. They believe some of their customers have to be able to drive by the hotel to find it, or for other reasons.

Though not so much anymore, I used to be Downtown frequently, before installation of the N-S light rail, when motor vehicle traffic other than buses was mostly restricted from it. In some ways, that phase of the mall was better for pedestrians, with generally less traffic during certain hours of the day, making it easier and more comfortable to leisurely cross the street. Some of the bus drivers though, took advantage of the absence of cars on the street, driving the transit mall as if they considered it a racetrack. Buses often roaring down 5th Ave were a kind of nightmare.

Portland does, arguably, have an 8-80 bikeway: The recently reconstructed segment of NE Cully north of Prescott.

But most people don’t know about it, likely because although its a significant piece of infrastructure, it sits largely disconnected from the bike network in a neighborhood that still needs many street/sidewalk upgrades to become truly walkable and bike-able.

Add in to the mix that the contractor didn’t do a great job on the basics (the street section for cars is asphalt and is lumpy/uneven and had to be re-ground) … multi-modal streets need to work well for all users or the political support for building more of them will be difficult to obtain.

This is not to say that the Cully project wasn’t a great bike project, but sitting in isolation it doesn’t make as much sense as a better-connected project that helps grow the network.

Cully is a great example of taking advantage of opportunities. The street had to be rebuilt, why not build it great? This approach will not yield an interconnected network in a built-out city like Portland, but it is definitely worth taking advantage of opportunities whenever possible.

I think cully is a good example of a bike “sidewalk” as opposed to a cycle track. The path needlessly twists and turns every block. And by blocking cyclists from view behind a wall of parked cars the city exacerbated right hook risk. I feel far safer taking the lane on cully.

I like that in one of the pics of The Indianapolis Cultural Trail there’s a bioswale as a buffer… that’s a good buffer to catch runaway vehicles before they mow down bikes and peds…

I’d like to see more on Geller’s commuting numbers. If I read the table correctly, it notes a 13% bike mode split of all trips. Is this correct? If it is, I find it highly dubious. Perhaps this was intended indicate the mode split of work trips?

Also, the term ‘interested but concerned’ sounds like what someone’s mother would say upon learning that their 16 year old is considering getting a tattoo. It isn’t very descriptive of the untapped cycling demographic. Instead, the term I use in my practice is ‘capable but cautious’. Seems a bit more descriptive of those who would ride if only they had protected bikeways.

The footnote in that slide seems to imply the area includes inner neighborhoods, but excludes the Central City. This inner neighborhood ring is the sweet spot for bicycling. Also, since he’s referencing the new Metro survey, my guess it really is referring to all trips.

I dispute Roger Geller’s claim that “…change is incremental.”

As I look at the bikey stuff PBOT has done during his tenure it is glaringly obvious that his organization has few, if any, designers who understand the dynamics and dangers of urban cycling and are capable of responding with realistic enhancements to our streets and, especially, our intersections. At least one person has been killed believing that green paint confers absolute right-of-way at intersections, and there are many others suffering from the same misapprehension, but who have been lucky so far.

Most importantly, his category of the “strong and fearless” cyclist is ingenuous to the point of inanity. It is obscenely dangerous. I do not want to fly with a fearless airline pilot; neither do I want to ride Portland’s streets near a fearless cyclist. Robert Hurst, who knows a few things about urban cycling, said we should, “Ride with fear and joy.” Amen!

Geller’s apprehension of PBOT’s methodology and goals as “evolutionary” may well be correct, but it is a dead end and deserves to become extinct.

If we are to progress Geller must go.

Do you even know the meaning of the word ‘incremental’?

I wouldn’t blame Roger alone, there are other good-intentioned staff at PBOT who are even more responsible for the errors and omissions than Roger is.

SW Broadway doesn’t count. I regularly see TriMet busses go all the way to the curb to load & unload passengers if there are no cars parked in the way. Bus 68 does it quite often in the mornings.

The mode split numbers are not for commuting but for all trips, according to the report released by Metro.

The Kent Ave design is about what I’ve imagined would work best in heavily used bike/ped/auto business districts like NE Alberta, i.e.

– single one-way auto lane, with speed lowered (currently 25 mph)

– two way curbside cycle-track, separated by…

– buffered auto parking

– other measures to help steer through traffic to nearby arterials, i.e off of Alberta and over to Prescott and/or Killingsworth.

Implementation on NE Alberta could initially be at least between NE 10th and 33rd Ave’s, and then expand the design further westward, either in response to growing use/demand, or in anticipation of it.

Where would you re-route the Trimet buses? They go both ways on NE Alberta, in that section.

A little late to the party here.

The Indy trail is an expensive toy, not a transportation tool! Whats the safe operating speed? 7mph? I’m surprised that NACTO used this as an “ideal” to hold up.

Those blocks used to pave the bikeway are super expensive, will become very bumpy as they heave, age and erode, and with the lack of MUTCD traffic markings, just invite pedestrians to walk on it. Nearly 80% of the independent photos I’ve seen of it have pedestrians preferring to walk in the wider bikeway.

And its not even well designed! It’s just a fancy looking 1970’s era sidepath with hardly any of the safety features of a well thought out modern cycletrack. In 5 years we will be talking about the mistakes of this trail.