It’s been just over two years since we sounded the alarm that a major effort at the Oregon Department of Transportation to better understand the state’s electrification needs was missing a key ingredient: bicycles. Despite skyrocketing sales growth and vast potential to serve the mobility needs of many Oregonians, ODOT’s Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Analysis (TEINA) initiative barely considered e-bikes at all. It gave just passing reference to them as “micromobility” devices and perpetuated the false idea that only cars and trucks can be EVs.

With the release today of the Electric Micromobility in Oregon (EMO) report, ODOT has taken a big step to remedy that oversight. BikePortland was given an early look at the report and we were able to ask one of its authors a few questions about it.

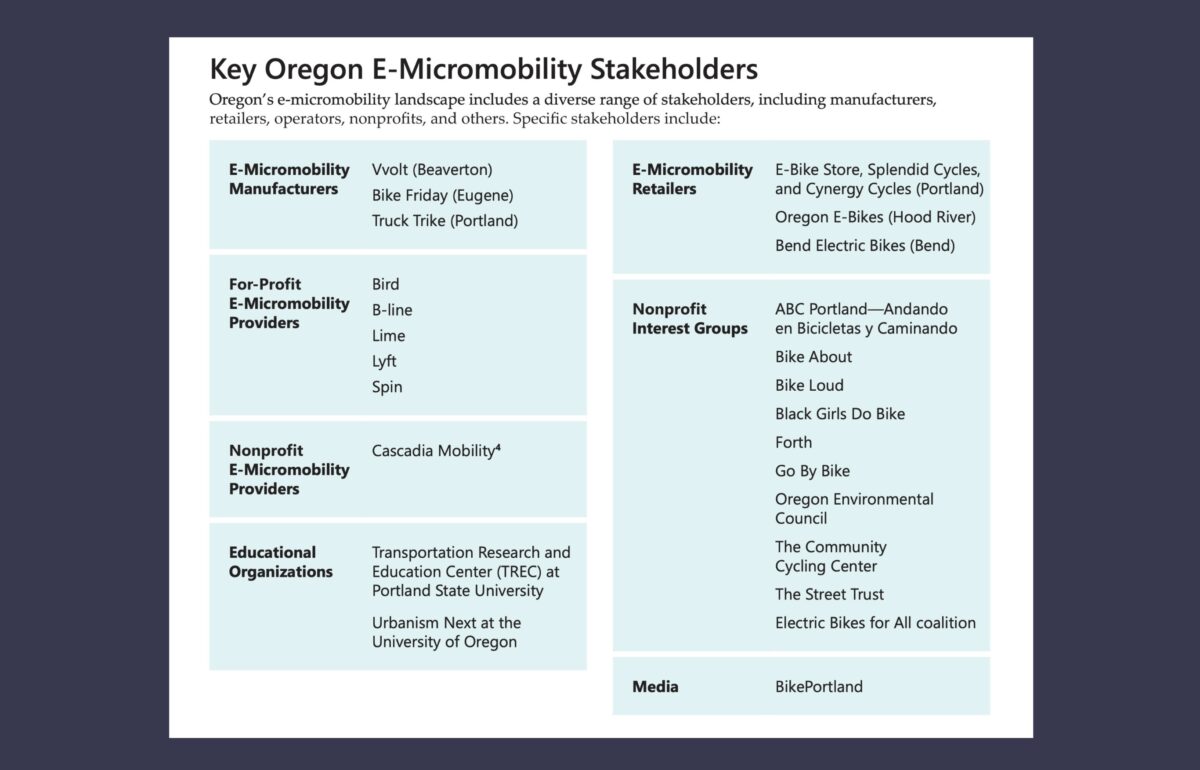

The report comes out of ODOT’s Climate Office. It was co-created for ODOT by Kittelson & Associates and the nonproft electric vehicle group, Forth. John MacArthur, a noted e-bike expert from Portland State University’s Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) was also on the team that produced the report.

In addition to being the first and most supportive document on e-bikes ever produced by ODOT, the 40-page EMO report gives bike advocates and policymakers a lot to chew on. It considers the use of e-bikes and scooters both by individuals and as part of shared rental programs like Biketown. The report should also put wind in the sail of House Bill 2571, the e-bike rebate bill currently being considered by the Oregon Legislature (the bill’s first public hearing was recently postponed in part to give lawmakers and supporters time to digest this report.)

The report still categorizes bicycle EVs as “micromobility” alongside electric scooters, segways, and other devices. This is unfortunate because no one outside wonky bubbles knows what “micromobility” is, which makes it easy for policymakers to forget about and marginalize. (I prefer to not use that term because I want people to think of bicycles when they think of EVs (since bicycles are technically electric vehicles as per Oregon law), so I’m going to start using “micro-vehicles” and see how that fits. The report also gives a nod to electric freight delivery trikes, which are hardly “micro”. ) With this small framing quibble aside, the reports findings should help further ensconce electric bicycles into Oregon’s transportation policy framework.

In addition to giving elected officials, advocates, and policymakers an excellent overview of the e-bike market and its exciting potential, the report offers a solid list of recommendations and “actionable strategies” that will be necessary to reach it. Just as important as the solutions it outlines is how the report clearly lays out the challenges that face more widespread adoption.

In a finding that will surprise no one who’s been around the bike advocacy space for more than a week or so, the report states that, “By far the largest barrier to e-micromobility is the lack of safe and connected infrastructure.” This is a problem advocates have raised a flag about for many years in calling for wider and more protected lanes for e-bike and scooter use. The report calls out this lack of safe space specifically in a section titled, “Right-of-Way Allocation”:

The Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Design Guide and ODOT’s Highway Design Manual specify that bike lanes and multiuse paths must be at least 4 feet and 10 feet wide, respectively. Neither document mentions e-micromobility devices (Oregon Department of Transportation, 2011) (Oregon Department of Transportation , 2023). Because they are often wider than standard bicycles, e-cargo bikes have trouble operating within these standards. In areas with limited space, the wider footprints and faster speeds associated with some e-micromobility devices can also cause safety and operational conflicts with other modes. Since e-cargo bikes can be as wide as 4 feet, Oregon’s minimum width standards for bike lanes and multiuse paths may not allow for safe passing opportunities.

According to the report, lack of space on the road is just one infrastructure problem we need to fix. The others are a lack of secure parking, a lack of integration with public transit (for shared systems), and the lack of charging. This last point is something we’ve harped on for years (only to have many folks tell us it’s not an issue because e-bikers can just charge at home), so it’s nice to see this issue spelled out in the report. “Not everyone can easily charge their device at home,” it reads. “People who make longer trips or use their e-bikes more frequently may also need access to public charging.”

Other major challenges listed in the report include: high purchase costs for micro-vehicles; the need for data from bike and scooter share providers; making sure access to them reaches underserved communities; a confusing regulatory environment; a lack of awareness of micro-vehicles in general, and a lack of funding to operate shared bike and scooter systems (especially for smaller cities)

Beyond the call for more road space for micro-vehicles, the other two major policy recommendations that caught our eyes were strong support for e-bike purchase incentives and a call for Oregon to establish “zero-emission delivery zones” to reduce congestion and emissions.

Jillian DiMedio is a senior transportation electrification analyst at ODOT’s Climate Office and was one of the report’s chief authors. Check out our Q & A with her below:

Why did ODOT commission this report?

In 2021, ODOT published its Transportation Electrification Infrastructure Needs Analysis (TEINA), which identified Oregon’s electric vehicle charging needs over the next 15 years as the state works to meet the zero emission vehicle goals outlined in Senate Bill 1044. While this study included electric micromobility as one of its nine transportation use cases, it became clear early on that this rapidly growing sector has its own unique benefits and barriers that needed to be more closely researched and understood by ODOT. This sentiment was echoed by the micromobility stakeholders that participated in TEINA listening sessions in the Spring of 2020.

In short, ODOT wanted to better understand a rapidly growing sector which will play an important and growing role in serving communities’ transportation needs and in reducing GHG emissions from transportation. The study sought to answer questions about the industry – its history and impact in Oregon, the benefits of and barriers to adoption and best practices and strategies for encouraging widespread use.

Where will this report live, administratively-speaking?

This study is not an official planning document but rather a research paper conducted to enhance understanding of a rapidly growing industry. ODOT’s Climate Office and Public Transportation Division, both of which work on micromobility, are developing an approach to implement the relevant recommendations in the study.

I do also want to note that ODOT just recently hired a new staff member in the Public Transportation Division (PTD) – a Micromobility and First/Last Mile Program Coordinator – that will be dedicated to promoting micromobility in Oregon. This person will develop and implement at statewide strategy for first/last mile connections with a focus on micromobility options, and will certainly be referring to the report’s findings and recommendations as part of this effort. She will also support ODOT’s existing Transportation Options program and the new Innovative Mobility Program, as well as PTD’s broader efforts to build an integrated, statewide public and active transportation network.

What was your goal with this report?

ODOT is committed to reducing emissions from the transportation sector. This means electrifying cars, trucks and buses and using cleaner fuels, and it means reducing the miles driven in Oregon by supporting transportation choices such as transit, biking and walking. The emergence of electric micromobility devices presents a unique opportunity to advance these efforts, as these devices are appealing to a broad range of users and have diverse applications. ODOT recognizes that the increased use of electric micromobility devices like e-bikes and e-scooters is an important tool in the toolkit for reducing the climate impacts of transportation.

With this in mind, the goal of the study was to do a deep dive into the electric micromobility industry – industry trends, the market potential, best practices from around the world in promoting adoption – so that we and other decision makers in Oregon could make educated decisions about how to design policy and programs to support continued rapid adoption.

What do you feel is the number one thing ODOT should prioritize from the report’s recommendations to encourage e-bike and scooter use?

What is clear from the study conclusions is that successfully promoting electric micromobility in Oregon will require a collaborative approach across many jurisdictions and stakeholders. There is a lot ODOT can do to facilitate the growth of this industry alongside our partners. As highlighted in the study, safe and connected infrastructure is a key factor in promoting and supporting the adoption of e-micromobility. ODOT will continue to prioritize the expansion of supportive infrastructure, as demonstrated by ODOT’s growing investments in programs like Great Streets, Safe Routes to School and the Innovative Mobility Program.

The study also highlights the need for a supportive ecosystem, which includes secure parking facilities, public charging, the availability of adaptive devices and equity-centered programs and policies. ODOT can serve as a convener for this supportive ecosystem. And we know that outreach and education are essential to shift the perception of e-bikes from one where they are used primarily as recreational devices to one where they are considered viable modes of transportation, for all sorts of activities. Lending libraries and shared micromobility programs can help shift the perception and ODOT will continue to promote these as well.

You can learn more by reading the full report or check out the executive summary if you are pressed for time.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Good to see an analysis of bicycle path and lane widths as part of the report. 5′ has always been very narrow for a bicycle lane. Some 4′ lanes, such as northbound Interstate Ave up the hill from Greeley Ave to Fremont St. have been sloppily restriped over the years and are only 46″ wide now. So a wider minimum standard would at least protect an actual 48″ minimum.

Maybe as part of the incentive package deal they could offer a $15 incentive on non-electric bicycles as well. By waiving the bicycle excise tax. It would only cost them $10 per bike to do it! (Since some of the bike tax revenue just goes to pay for the collection system)

Ted Buehler

I always see transportation experts relegate ebikes (and bikes) to “micro” solutions, or something about the “first/last mile problem”. I think this is worth analyzing – because I really do not think this is how regular people actually interact with transportation in general, and certainly not with ebikes.

When I hear my friends talk about how having an ebike has changed how they get around, they talk about using it as a car replacement, or as a commuter-extender/speeder up. None of those things strike me as “micromobility” – they are just how people get around regularly. Micromobility refers more to bike/scooter shares, and ODOT lumping a sharing system with something people personally own is absolutely ridiculous and unserious.

I wonder if the ‘micro’ comes from the lens of always viewing the transportation system for multi person, multi 100 pound vehicles (personal cars, freight, buses, trains). Unfortunately in our heads this gets translated to micro-distance and also micro-priority.

As I understand it, the last-mile/micromobility terminology is largely related to things like delivery services in urban areas (where the last mile can be >50% of cost of delivery). In this context, I think it makes sense – ebikes/trikes and smaller delivery vehicles are “micro” relative to the big trucks that usually do the job. It’s just really frustrating to see my personal choice for 75%+ of my transportation needs being conflated with a bike share company run by a tech taxi company.

that’s my feeling too. Whether ODOT does this stuff with malice or not, it sure smells fishy to me when they constantly find ways to show they really care about non-car stuff, but then only a tiny little bit… and never in a way that creates openings to threaten the car and freeway stuff. They do this same thing (with the legislature’s help) when they pass billions in status quo highway funding, then give a pittance to Safe Routes or other non-car program just so they can say, “we did something for safe routes”. It’s so maddening.

Yeah it just doesn’t add up to me. And that entire report has no recommendations for recouping lost gas tax revenue.. which is a primary way ODOT makes money. ODOT is crazy if they think subsidizing charging infrastructure/EVs in general is a good idea if they don’t have a funding mechanism to replace the gas tax! But hey, if that’s what finally sinks ODOT and car infrastructure in Oregon you won’t hear me complain

I love the idea of zero-emission delivery or “ZED” zones being apart of the Portland Freight Plan/Transportation Systems Plan. It seems like a digestible, easy to conceive expectation to move toward expanding EV and bicycle freight delivery.

I really dislike the ZED rhetoric, since it gives people the impression that EVs are zero-emission vehicles. They aren’t – they emit whatever fuel was used to charge the batteries. PGE is the worst offender in this regard. All of their literature “green washes” the sources of electric power, which right now is about 30% coal from Idaho. Just cuz nothing is spewing from a tailpipe as you pedal or drive an EV doesn’t mean the energy source is clean.

Electric vehicles are about twice as efficient as gas cars just by virtue of running on an electric motor instead of an internal combustion engine. ICEs in modern vehicles operate at around 20%-30% efficiency, whereas a steam turbine in a power plant runs at about 40-50%. And that’s not even considering the amount of energy that goes into oil extraction and refining. Although to be fair, the environmental cost electric car batteries is also very high if we want to go down that rabbit hole.

Also, according to the NEI Oregon has 0% of it’s electricity produced by coal (https://www.nei.org/resources/statistics/state-electricity-generation-fuel-shares). I see 1/3 to 2/3 split on green vs. fossil fuel for Oregon, which is quite good relative to lots of the rest of the country.

There is certainly more work to be done on cleaner energy on the grid, but electric vehicles are certainly more efficient in terms of energy at the time of use.

“As highlighted in the study, safe and connected infrastructure is a key factor in promoting and supporting the adoption…” –of bikes!

I’ve waited long enough on ebikes to keep my stubborn hold-out cred but I’m on the cusp of flipping the script. When I encounter committed bike riders who have gone electric they say they are riding more: more places, more miles, and for more reasons. Some who had a car sold the car.

If we build infrastructure to favor ebikes I’m going to feel pretty free to ride whatever bike is at hand on it. After 30 odd years of NASCAR-lite, potential brushes with sloppy ebikers don’t trouble me much. I’m bemused at the prospect of bike cops riding bike routes to regulate what, where and how people ride bikes.

One thing I’ve discovered in shopping ebikes is that the market has gone right past my notions of how much power an ebike requires. It was predictable. One thing that might save us from mere anarchy is the cost of bigger batteries (and replacement batteries) and the trade-off between range and speed.

One local shop is assembling their own battery packs which shoots down one of my categorical objections to ebikes. If they are doing assembly, presumably they could service a battery pack with a few weak cells.

If you swap a 0.5 kW controller with a 5 kW controller on an electrified bike speed-limited to 15 mph, the range difference is marginal unless you break the thing from the extra power. So the range/speed tradeoff won’t save us from power anarchy. But I don’t see too much anarchy in power alone anyway except that it eliminates the need to pedal. (Yes, that even includes the cadence sensor “but I have to pedal to make my bike go” bikes which is a large fraction of ebikes. If your gajillion pound cargo bike puts forth 100000000000 W when you expend 5 W to move the crank past one of the magnets, it’s effectively a grip throttle.)

I admit to being a bit fuzzy on the details, my physics are stale, but the key words might be “speed limited.” Many ebikes are not, and people who choose to go 30 mph will have to turn back sooner or else pedal home on a bike that is suddenly heavy and kludgy.

I’m pretty sure ebike shop workers hate the question “how does it pedal without the motor?” and the answer begins “If you have to ask…”

100% right. And not just sooner but much sooner since drag force increases not just with speed but with the square of speed.

There may be a lot of whining, but maybe it would be good for the U.S. to unify ebike regs and switch to the lower 25 km/hr (~16 mph) speed regulation in the EU and other countries.

On my commutes I’ve seen more people e-scooting (rented and owned) than biking but both the ODOT report and this piece essentially ignores e-scooters.

Sorry, Jillian, but those are just words. To see what ODOT is actually committed to, you have to look at their actions – what they spend money on – and that’s all about making it easier to drive a car or truck everywhere. The money ODOT spends on non-motor-vehicle infrastructure is a pittance compared to their spending on huge motor-vehicle-only projects like the Rose Quarter freeway widening project.

Also remember that electrification doesn’t reduce remissions unless the sources of electricity are clean. Right now every EV in Oregon is a 30% coal-powered vehicle, since PGE buys electricity from coal-fired plants in Idaho (and doesn’t report them as Oregon-generated electricity).

I won’t believe ODOT’s rhetoric til I see them act (translation: spend) most of their (no – OUR) money on projects that make it easier to get places other than in a car or truck.

I agree with this except the second paragraph which is just missing the point.

Right now every ICE car is 100% fossil fuel powered, switching to e-bikes or e-cars ls definitely going to reduce emissions. 30% coal is better than 100% oil especially when considering efficiency and refining and transportation as someone else pointed out.

No thanks. Ebikes will never have the carbon / environmental footprint of a real bike. Why are we rooting for lithium mines?

Electric vehicles have batteries which weigh 100x more than an ebike battery. If you are looking to dismantle global systems of neocolonial exploitation involving mining lithium, I would think that the nascent ebike industry would be among the least impactful places to start.

So what is the argument here? The lithium batteries or just ebikes in general? I’m curious to know why people hate ebikes. Is it because they’re motorized and that you don’t like getting passed? Or is it truly because people are environmentally aware and dislike anything with lithium in it? I would like to use my rotary dial phone, but I don’t always carry change on me.

I don’t like lithium mining, nor do I love my mobile phone. But what am I to do if I want to live in a society that requires me to use these things?

Who hates e-bikes?

They are not hated, just over rated. They are not making any difference.

Bicycle riding (both regular and E-bike) is dropping, not going up.

I ride every day around the east side of Portland, where are they?

I know we all wish people were riding them and this site keeps telling us that the e-bike business is booming, so why are the bike lanes empty?

And a real bike will never have the carbon / environmental footprint of walking or other unsavory solutions, and yet here you are.

Bikes are so incredibly efficient that putting a motor and battery on one is orders of magnitude more efficient than an electric car. It’s incredible. The batteries are so tiny you could charge like 10 of them throughout the day on one rooftop solar panel (just as a frame of reference).

I’m interested in the “lack of charging“ claim. All e-bikes I’ve owned—three, only one of which is fancy, the other two are very entry level—have removable batteries. Is this not standard in all ebikes? Just turn the key to pop it off and plug in next to your coffee maker.

Storage of the actual bike (ebike or standard, regardless) is a massive issue, but is charging really? Honest question. I really don’t see it.