While the cost of bread or milk seems to change daily these days due to inflation, one thing has stayed constant for the last ten years: TriMet fare. It costs $2.50 for a two and a half hour TriMet pass, which allows you to ride both the bus and MAX.

But Portland metro transit riders are likely to see a fare increase, and it might happen sooner rather than later. TriMet leadership, who say they’re grappling with budget deficits, have floated the idea of a fare hike for some time. At a Board of Directors retreat Wednesday, they made concrete moves toward doing just that.

Stories in the Portland Mercury and Oregonian provide detailed accounts of TriMet’s budget woes and how agency leaders think a raise hike will solve some of the problems they’ve been facing.

Federal pandemic relief funds have been TriMet’s saving grace over the past two and a half years, but that money is dwindling fast. The other way the agency keeps its head above water is through an employer payroll tax.

At yesterday’s board meeting, TriMet’s finance director Nancy Young-Oliver outlined the potential plans for how they’ll proceed. There were a few options on the table: a 20 cent fare increase starting in September 2023, a 30 cent fare increase starting in January 2024, a 40 center fare increase starting in September 2024, or no fare increase. After deliberating and discussing concerns, the board decided to go forward with the 30 cent increase proposal.

“If we ignore the issue right now, it only gets worse as the time goes on,” said TriMet board president Linda Simmons at the board meeting. “What I’ve always believed is that you make change in smaller increments over time as opposed to waiting until you have to make really large changes.”

Here’s how the changes would play out:

- Adult 2 ½ hour ticket—increase 30 cents to $2.80

- Honored Citizen 2 ½ hour ticket—increase 15 cents to $1.40

- Youth 2 ½ hour ticket—increase 15 cents to $1.40

- LIFT paratransit single ride—increase 30 cents to $2.80

High fares, low ridership

In a time when transit ridership has declined significantly due to the pandemic’s effect on commutes, some people see a fare increase as very risky business that could threaten their ability to win back customers. But proponents of the decision say the benefits of more revenue will balance this out.

TriMet plans to use the new income to improve ridership numbers by doing things like tackling cleanliness on the bus and light rail to make the “on-system customer experience” better, increasing marketing to attract new customers and hiring more people to increase fare compliance and avoid financial hits from fare evasion.

If the agency raised regular fare prices, reduced fares would also see a price hike. TriMet’s Honored Citizen reduced fare program is robust and gives a discount of up to 72% to people over the age of 65, people with disabilities and people who earn low-incomes and qualify for other government assistance programs like SNAP and the Oregon Health Plan. According to TriMet’s website, this program has had 46,000 people enroll since 2018.

Even with a price increase, TriMet officials have a plan to keep people actively enrolled in the Honored Citizen program by getting more people who qualify signed up, renewing current subsidy programs like the youth pass that allows Portland high school students to use TriMet for free during the school year (they also have a summer pass pilot program underway). The agency would also look into other funding opportunities through the Statewide Transportation Improvement Fund and overlapping grants they can apply for with outside agencies like the Department of Human Services, medicare providers and public housing operators.

If TriMet doesn’t raise fares, leaders say they’ll have to start cutting costs, threatening employee layoffs and more transit service reductions. These would both be detrimental to the agency, which has already been experiencing a severe operator shortage that has already forced them to reduce service and cut some routes.

Earlier this fall, TriMet made waves among transit enthusiasts when they released their Forward Together draft service concept, which outlines potential new bus routes across the Portland metro area. Many transit advocates are excited about this proposal; but some of these same people have spoken out against the potential price increase. It will be interesting to see how advocates weigh the possibility of service cuts to the potential ramifications of a fare increase – because according to TriMet, it’s one or the other.

A different solution?

Are there really no other ways for the agency to stay in the black? TriMet surveys have shown they lose millions of dollars a year due to fare evasion, so one option could be to increase compliance. But more security has its own pitfalls if it’s modeled after traditional police or other armed personnel. An approach like that is likely to lead to unfair enforcement and possibly discrimination against some riders.

A new report, Alternatives to Policing on Transit, released by Portland non-profit OPAL Environmental Justice, imagines a different scenario. What if, instead of raising fares or beefing up enforcement, TriMet abandoned fare compliance measures altogether?

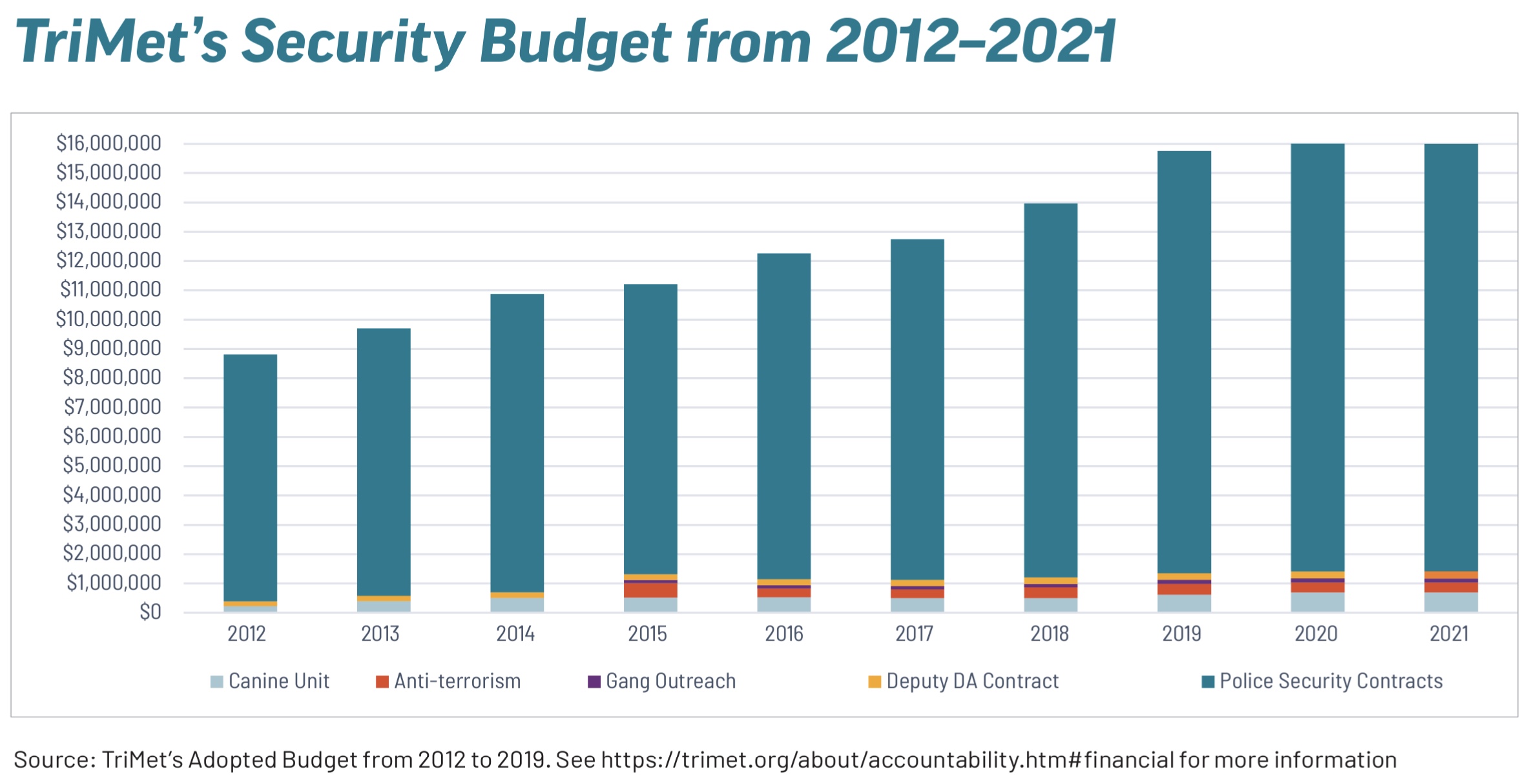

The report points out that TriMet’s budget for fare collection is substantial – up to a quarter of the passenger revenue TriMet collected between 2012 and 2019.

“TriMet’s argument that passenger revenue is one of their biggest sources of operation costs seems a little bleak considering the costs that go into fare revenue collection and fare inspection,” the OPAL report states. “The burden of fare inspection lies not only on riders and their engagement with fare inspectors, but also on TriMet’s budget.”

The report also posits that TriMet could save money by decreasing their security presence and hiring more community-centered, unarmed crisis workers. This could look like the Streetcar Rider Ambassador Program, which won an Alice Award this year for its equitable approach to safety on public transit.

Ultimately, this report echoes the claims made by many public transit and equity advocates, who think an equitable transportation system that truly aims to get people out of their cars and onto the bus or light rail will be fare-free. The report states:

“We see a world where transit is a center of community building, where people don’t have to live in fear of police violence — or any violence — in public spaces, and a world in which transportation is a free, public good that is understood to be a human right.”

Given the recent vote by TriMet’s board, a fare-free future seems unlikely.

What’s next

In a statement Wednesday, TriMet said they’ll launch a public outreach campaign that will include events and an online survey starting in December 2022. They plan to take feedback through this spring and the ordinance will be read at the April 26th, 2023 board meeting. There will then be a public forum and vote on the increase at the May 24th meeting. If you want to share feedback, you can sign up to testify at the start of any Board of Director meeting. Stay tuned for more details in the coming weeks and months.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

The point of any fare increase by any public transit agency in the USA (and only in the USA by the way) is not to raise more revenue, which it won’t or only marginally, but to decrease paratransit ridership for those particular people with disabilities who aren’t able to ride the bus or light rail (some are able to use the bus but many cannot), which will save TriMet millions annually in operating (driver) and vehicle (van) capital costs. As our population ages, those who need to use paratransit services keep increasing far more rapidly than those who use regular public transportation even before the pandemic.

Paratransit services (also called lift or dial-a-ride) are typically door-to-door taxi services that TriMet is required to subsidize in return for federal and state subsidies, per the 1992 ADA laws, for people with certain qualified disabilities. The cost of the service is typically 10 times that of “fixed route” transit, but they are only able to charge up to twice the regular fare for each ride. So if the regular fare is $2.50, then they can charge up to $5 per ride, but the rides typically cost TriMet $40-$50 in terms of personnel, vehicles, overhead, and so on. (Although Trimet charges the same for paratransit as regular bus, the concept that a single ticket could be for a round trip is impossible to schedule for paratransit – the cost for a round-trip on paratransit/lift is always 2 tickets or $5 per round trip.)

The price elasticity of paratransit is normally very steep – even a small fare increase will have a huge impact on paratransit useage – and a $0.30 fare increase in paratransit fares could have a devastating impact on the mobility of the disabled.

David, yes an excellent and often over looked point by most council members and transportation engineers/ planners. ADA para transit trips – federally required w/i a radius of a fixed route transit stop – are ‘breaking the bank’ for most public transit systems. I have often brought this point up as to why cities (& transit agencies) would be smart to connect major fixed route transit stops to side street residential areas so that more para transit passengers can have access to and the choice of the more frequent regular service.

Todd, that radius is within 0.75 miles of a fixed bus route, by how the crow flies (as opposed an existing street or sidewalk network) unless there is a loop in the fixed route transit – then everything is included even beyond the 0.75 miles – so there isn’t much of an economic incentive for transit systems to connect to side streets unless a community has deliberately designed itself to accommodate public transit (like a TOD or an older pre-car city). I think it would be good public and social policy to rewrite the national ADA code to encourage such street and sidewalk network connectivity, but there are lots of other equally awful and wasteful policies on federal bus acquisition incentives versus repair that basically limits buses (and MAX cars) to 12 years in any fleet and an 83% FTA capital cost subsidy which IMO encourages shoddy bus quality from US manufacturers, “buy American” clauses that effectively prevents US transit systems from buying better-quality foreign vehicles, and so on.

For those communities who don’t want to “break the bank”, FTA has encouraged communities to have “hub and spoke” transit systems which avoid the loops (crosstown routes) but have the unfortunate consequence that a even a local transit trip can take over two hours since you have to go to the hub to transfer, then back out on another route. They also encourage transit systems to charge a paratransit fare that is up to twice the regular fare (and usually stays fixed at 2x) to depress paratransit use (but also personal mobility for the most vulnerable users, alas.)

Here in NC as in much of the USA, nearly all cities employ hub-and-spoke transit systems, which typically yields very low ridership, extremely inefficient routes, and poor transit connectivity even for cities like Charlotte with frequent services, light rail and streetcar (they have it all and are expanding). Cities like Portland, Houston, DC, and NYC with a criss-crossed transit systems and frequent routes generally get much higher ridership, but at a cost of increased paratransit costs and constant battles to rein in costs and/or cut comparatively inefficient routes. There is no happy medium in the USA – it’s usually one or the other.

The basic lesson we’ve learned here in NC is that no one will willingly use a city bus unless it gets them to their destination in roughly the same time as driving, no matter how frequent or safe the service. Over 95% of our users are “captured” riders, people who cannot drive (never learned how, too young or old, too poor, disabled, has a DUI conviction, etc.), who are almost all black, immigrant or Latinx, and the other 5% are “choice” riders who have other viable options. Fully half of my city has no transit service whatsoever, including the downtown core, the airport, and most industrial employers – we are still stuck in a segregated 1948 on our routes, though the smelly textile, tobacco, and furniture factories closed decades ago.

In cities with higher ridership like Portland or Vancouver BC, the portion of choice riders is much higher and the service area is nearly complete, and in much of Europe and Asia it’s the majority of users – but then they have greater subsidies and far more progressive policies that actually encourages transit use and building densities and network connectivity that help encourage transit efficiency.

The ADA was signed in 1991, not 1992.

I have not kept up on the qualifications for Lift, or Paratransit, The one or two times I have looked into registering, the registration process was daunting.

Dial a ride, at least in Southern California, was what came before- it’s been a while, so I could be wrong about that, I just remember it disappeared. Dial a Ride was an on-demand service, Paratransit is not. You have to schedule with them at least 24 hours in advance, as far as I know. I have heard horror stories about people getting stranded using Lift & Paratransit.

This is a perfect juxtaposition to the article about the climate activists who are letting the air out of tires. People will drive as long as there are no alternatives. And Trimet is a poor alternative to driving from a scheduling point. Real transportation needs to be frequent and consistent. On the west side most buses are scheduled every 30 minutes. I ride the bus and am often delayed and frustrated. You cannot live your life with busses that run so infrequently. Instead of vandalizing and inconveniencing individuals, the immature activists should turn their energies to making transportation better and toward encouraging development that allows for easier walking and biking. As long as our cities are laid out the way they are, people will drive out of necessity and shouldn’t be punished for living within the parameters our society has created over 80 years. The climate crisis will not be solved by individuals changing their behavior, it will be solved by societies making different choices and priorities. If we want people to drive less then make mass transit better and make cities more walkable.

Continued: raising prices has the potential to lower ridership which

then leads to cuts in service. A proverbial death spiral. Michelle Wu, the new Boston Mayor made a few lines free and ridership increased. If we want more cars off street, make bus service frequent but don’t keep raising fares, which as Dave Hampsten pointed out, don’t really contribute much to operating costs.

Hate to say it but the Max trains are basically already free with no enforcement.

As for buses, even with the bus driver at the front door, I’ve seen many passengers allowed onboard without paying a fare or having a pass.

Why don’t they just get rid of the pretense and go completely free for everyone?

If you had a cushy late model SUV, would making transit free be more or less likely to encourage you to ride it?

Trimet lost me after several three-hour-plus commutes to get from work to home. I could live with the 90-minute commute to work in the morning, but vagaries of afternoon scheduling made getting home a true test of patience. The evening timing just kept getting less and less predictable. Given my round trip by car is only 90 minutes total, it’s not a reasonable trade to use Trimet. I really wish they’d step up the service and frequency levels and stick to their published schedules. A more direct route from St. Johns to Hillsboro would also help.

Sigh…

One could do both of these things and also do little to address the climate crisis. I’m not sure you understand the math of our CO2e budget.

Where are these societies that have no individuals???

Oh, I’m pretty sure I understand the math. My point is that within the current structure of our physical environment, it’s not enough for people to focus on their individual carbon footprint. We live in sprawled cities that require a lot of energy to maintain. We ship crap all over. We import out of season produce from the other side of the earth, we build in ways that require a massive amount of air conditioning. The changes that are needed are at a societal scale. Those are the things that will address climate. How our built environment is organized. I take the bus and Max when I can, but it sucks that I am at the mercy of a schedule that isn’t designed for actually functioning. On the days I need to go into work my bus ride is an hour, when it comes on time. Driving would take 20 minutes. I also am not under the illusion that me riding my bike to shop or taking the bus to work makes any dent at all. I still live in a sprawled out city that requires a huge amount of energy to run.

How would you suggest they go about doing this, specifically? What steps should they take?

Lobby the state legislature to remove the payroll tax cap on Trimet. Lobby Trimet to increase the tax and use the funds to roughly double the frequency and coverage of the busses and MAX. Lobby Trimet and Metro to build social housing on the park and rides.

Just curious, what’s your definition of “social housing”?

Government owned housing available to earners up to the 80th percentile, with cross subsidized cost-rents is how I’d define it.

Now that’s vague.

Government owned social housing in much of europe is 100% subsidized with the subsidy varying based on income/means. This is the primary transmission mechanism by which social housing pushes down housing costs of profit-based housing. If you support social housing but don’t see it as a mechanism to tamp down profit-seeking then your vision of social housing is very different from mine.

I don’t see it as vague at all. Cost-rents are exactly what they sound like, the total rent for the building equals the cost of construction and maintenance. Cross-subsidized means higher earning residents pay more in rent to so that lower earning residents can pay less in rent. Rents are set as a function of income, with the lowest income renters probably also receiving Federal vouchers.

You sound like a 1950s era real estate speculator who wants to kill public housing. Social/public housing only works to improve housing security if it does not pay for itself.

I can’t help but feel like you’re intentionally misrepresenting what I wrote, but whatever. For your edification: Austria uses cost rents in municipal, LPHA, and co-op social housing. Those cost rents are significantly below the strictly private market rate, and contribute to depressing the latter. The cost rents are low because a) the Landers typically contribute a ~30% subsidy to construction costs (either direct, or via long term low-interest loans) and b) because only the LPHA earn a profit. Moreover, there are semi-regular appropriations for major maintenance, at least in Vienna. The buildings do in fact, “pay for themselves” and rents are set to reflect that, however the construction and some of the maintenance is state subsidized. Have I clarified my position sufficiently to satisfy your deeply uninteresting pedantry?

Coop housing in Austria varies quite a bit depending on its funding sources and the governance of the coop. It’s not a monolith and its bizarre that you’d claim this. Likewise municipal social housing also varies based on city governance and program rules. Some social housing is exclusively for the very poor and homeless, for example.

Social housing in Austria is now primarily intended for low-income people but these households are allowed to age in place (and often end up paying higher rents as they become more financially secure). The idea that social housing in Austria is mean to “pencil in” is pure YIMBY BS. It’s also fascinating how you go from a general statement to narrowing down to one nation (and then still get it wrong).

A review from the LSE (you should read it):

https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/fnctvnuc._A%2Breview.pdf

This is an awful lot of money. The lack of maintenance and the lobbying campaign by developers to defund maintenance of public housing in the 50s and 60s is why so much of it was torn down.

Typical USAnian Fordist obfuscation.

Typical YIMBY reluctance to admit that they don’t want they were writing about.

Lobby TriMet to make their vehicles feel safe and clean so the people who have abandoned the system would consider coming back.

Not enough, yes. However, talking about and advocating for the ways to reduce CO2e individually (prefiguration) is essential to collective action. The idea that some “Daddy” government will be able to pass mandates that disrupt the USAnian lifestyle-as-usual without a high-degree of individual support for mitigation pathways is absolutely absurd, but many seem to believe this fantasy.

I will also add that if you are a “climate warrior” and are not attempting to embody these mitigation pathways in your own life, you should ask yourself whether you really believe this is a crisis. One of the ways we can collectively go after corporations and the rich that own them is by convincing people — a lot of people — that a better world is possible. How can we do this if we refuse to make the smallest of changes in our own lives. (There is a reason that Thunberg eats a mostly vegan diet, consumes relatively little, and does not fly — and it has f*** all to do with her carbon footprint.)

Most people don’t. It’s my perception that different subcultures in the USA tend to impose their own particular belief system on the climate crisis, regardless of the science.

For example, fossil-fuel powered personal vehicles represent a fraction of total transportation emissions and a small fraction of the CO2e emissions that matter for absurdly wealthy nations — consumption-based emissions. This is not to say that we should not rapidly phase out all fossil-fuel-powered personal vehicles — we should — but please stop pretending that new urbanist fantasies are equivalent to science-based mitigation pathways.

Oregon’s Consumption-based Emissions (Portland’s would be higher but this city has refused to even measure its emissions):

https://www.oregon.gov/deq/ghgp/pages/ghg-oregon-emissions.aspx

https://www.euronews.com/green/2022/04/13/sweden-heeds-greta-s-call-to-target-consumption-based-emissions-in-world-first

The sad thing is that compared to most places in America, you really don’t.

This is a comment of the weak fo sho

Some people will always think activists are immature no matter what they do. Activism is not supposed to be convenient, or wouldn’t be effective…but how would you suggest that activists turn their energies to making transportation better?

Last week in the late afternoon, I was on the Max in downtown, in a subway car barely a third full, heading east, when a fare inspector, in an all-black outfit, began their ponderous inspection. It made me melancholy to realize that the fare inspection was being undertaken in what used to be Fareless Square.

Do you recall why TriMet got rid of the Fareless Square?

I was there when it happened, but I forgot the year – was it 2012? They had lots of issues with fareless square – crime, drug dealing, fare evasion on the rest of the system – but there were huge benefits too in terms of tourism and ridership. The decision to cut fareless service boiled down to cost savings on fare evasion and raising more revenue during a period when many routes were being cut – there was already lots of crime on the other parts of the system, particularly in East Portland and Gresham. When did they eliminate the fare zones?

I’m not sure of the year, but my recollection is that the drug dealing was the proverbial straw. The point being that there are many unexpected consequences to seemingly simple proposals like “eliminate fares”. Well, now Lift blows up and you have folks doing drug deals on the Max and every seat is occupied by someone trying to get some sleep.

Even if ridership increases, they may not be the “right” riders*, and if more people may end up driving, support for the system falls, and budgets crater, we’re all worse off.

*I realize that may be inflammatory language, but that’s how it is.

I think a lot of people didn’t dive very carefully into the results of free fare programs in places like LA. I’ll speak to that, because it’s the system I grew up with and that I know the best. Unlike Portland, LA Metro doesn’t have fare capping. It’s fare have been $1.75 per ride for ages, but four rides would run you $7, whereas here it runs $5 for unlimited rides. When LA eliminated fares, they did see an increase in the number of rides taken, but the number of riders remained flat. That is, free fares did not bring more people onto the system. Instead, people who already used Metro used it more frequently, often to replace trips by on foot. I if TriMet went fareless I wouldn’t anticipate an increase in riders, nor would I expect a notable increase in rides, as folks who are already riding don’t face a financial barrier to riding more. When polled, the majority of riders across income levels prioritize frequency, speed, and safety well above cost.

Moreover, the cost of fare collection is relatively flat, it doesn’t cost more to collect additional fares. While revenue raised by fares currently is about equal to the cost to collect, that won’t be the case if and when ridership increases.

Some folks have advocated increasing the payroll tax to cover the cost of fares. TriMet is already increasing it to the maximum allowed by state law ~0.82%. They are currently limited to increases of 0.01% per year. If you, like me, want to see that limit raised (in France, which also funds transit through payroll taxes, the rate is set at 2%) contact your state representatives and push for it.

When TriMet had double its current ridership, from an energy standpoint, it was about break even with everyone driving a small single occupancy vehicle. That wasn’t great, but now it’s half as efficient.

If we double the frequency, we’d need 4x the current ridership to simply get back to the efficiency of single occupancy vehicles. That doesn’t seem even remotely feasible.

I understand emissions/efficiency is not the only metric to measure transit with, and maybe isn’t even the best one, but as someone who prioritizes emissions reductions above most other things, it’s an important one for me, especially when TriMet is powering most of its fleet with diesel.

There are a lot of ways that transit seems fundamentally broken, and I’m not sure there’s enough Other People’s Money available to fix it without a complete rethink.

I haven’t ridden Trimet in several years and don’t expect to ride anytime soon.

A few years ago I got a flat tire on my bike and decided to take Max to a stop nearer my home since it was wet, cold and dark. Surprise: none of the fare machines was dispensing tickets. I subsequently learned from Trimet’s website that fare machines are often down, but that is not a valid excuse for not paying. I guess that’s why they have gone to electronic payment only using your smart phone. I’m too old to learn that. It’s preferable to just ride my bike regardless of the conditions.

You can also pay with a Hop card and with a tappable debit or credit card right at the reader.

C’mon, J_R – the Hop app on your phone is free and (mostly) easy to use. You can learn it! Even an old dog can learn a new trick or two.

Yes, this is a national discussion now…and there seems to be four different paths that public systems are selecting:

1) raise fares through traditional fare hike (TRIMET);

2) raise fares ‘invisibly’ by raising the daily threshold for free trips, like moving from 2 trips to 3 trips (OTS, Honolulu);

3) cutting fares / holding price steady by using federal pandemic aid (CTRAN, Vancouver); or

4) making transit a no direct cost public service, aka ‘free ride’ or ‘zero fare’ for all routes (multiple agencies in US); and not just a downtown route or two.

Option #4 used to be almost impossible to discuss openly in the US until the pandemic. But systems like CTRAN and TRIMET, etc. should openly discuss it / study it as their percent of gross revenue collected through the fare box is very very minimal compared to other services (CTRAN = ~2% and TRIMET = ~7%). And if we were to dig deeper, the cost of passes / collecting / administering these funds plus the longer dwell times at stops may outweigh the income collected. And some systems make almost as much income from their money in the bank (interest income). If our public systems want more bodies on buses / passenger miles, then this option should be strongly considered, even if only for a 3 year pilot.

This! I’ve dug through TriMet’s detailed budget a few times and am pretty convinced that they actually would break even if they didn’t collect fares at all, given how much it costs to collect the fare itself. There’s the fare machines, the software for the machines, app development, the hardware on the buses, enforcement, and the cost of physically moving the physical money around. I just don’t see this big picture as part of the conversation, unfortunately.

Maybe they could even fix an elevator to two with the savings!

Every transit system I know in the USA has studied free service, but very few have fully carried it out beyond the pandemic period, and the few that have are generally very small systems that get subsidized by a major corporation or university, or in the case of Boston, a few select bus lines through a limited federal grant.

I agree that eliminating the farebox collection system has huge financial benefits of massively reduced costs of equipment and personnel.

The main issues against are:

Paratransit service would then also be free. In most well-run US transit systems, paratransit is typically about 20% of the overall transit operating budget, but in poorly run systems it can be as much as 50% of the budget. Making paratransit free would run the risk of effectively wiping out the rest of the system within a few years – and this has happened already in some rural and suburban systems with poor transit management.The public may no longer “value” public transit if it’s cost is free (or a nickle in the case of LA’s 1920s streetcar system – Who Framed Roger Rabbit) and may vote to remove any local transit subsidies.Farebox collection is used by many individual bus drivers to prevent problem passengers from boarding – as a first-line security mechanism.Many state agencies require a certain minimum fare structure for local transit agencies in order to collect the state subsidies, while the feds are more concerned about overall ridership for their huge subsidies – it’s a constant dilemma for many transit providers – more ridership for more federal subsidies versus more fare revenue that is matched by the state.

It’s almost as if the cost of driving a SOV car should cost even more in the U.S. to start paying for all those externalities.

If we had been taxing cars so much since 1913 I’d agree with you, but clearly we haven’t. As much as a lot of these externalities have much to do with suburbanization caused by the popularization of the automobile, suburban sprawl itself long predates the automobile – even the Romans had to deal with it – and public transportation, railroads, trolleys, horses, and yes even the humble bicycle have all contributed to our suburban sprawl. I’d severely tax not only SOV, but also SFR, the internet, cell phone signals, Amazon deliveries, imports, and anything else that has contributed to our rather wasteful ability to live in low-density communities so cheaply. Taxing the rich is pointless as they know better than anyone how to hide their income and assets from the taxman.

Our curvelinear suburban sprawl of the 50s through the present day were strongly encouraged by the influential Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio who thought such curved streets would reduce street horizons and increase property values, but even Frank Loyd Wright encouraged low-density car-centric sprawl. Anyone who buys property engages in property speculation whether they intend to or not, just as much as anyone who saves or invests money. We all contribute to the externalities that we are dealing with, just as our predecessors have, and we are all going to have to pay for it, one way or another.

If I were a TriMet administrator I’d be like an older friend at Intel and counting the days to survive until retirement. The only thing I’m sure of is that somebody thinks that there is an answer and they have the right one. I’m less optimistic.

Imagine if the Orange Line was never built: more room for potential improvement of the two current and different Amtrak lines and more and better buses.

But how would its 17 riders get around?

I’m a regular Trimet bus rider and I do NOT support the elimination of fares. People with jobs can easily afford the fares, and there are many programs that provide free bus passes for people who can’t afford them.

I see on a daily basis what a difficult job the bus drivers have in moving our huge homeless population around. If you eliminate the one tool drivers have to keep crazy people off the bus, driving a bus will become impossible. Right now it’s almost impossible to ride a lot of the buses, with large numbers of homeless people and their stuff (like huge plastic bags of returnable cans) trying to get on and off the buses.

Let’s listen to the workers and consider what they want before we make sweeping changes.

I’m sad to say that the homeless problem is the first thing I think about with free transit. At what point does the MAX/bus just become a mobile dorm room? I’d ride the MAX to work if I could work on my laptop the whole time, but I’m mainly concerned about it getting stolen. So security is an issue as well, and fares serve to provide a first line of defense. Unless Trimet starts having fancy “Pay” buses, and anything-goes Mad-Max “Free” buses, but that’s a whole other can of worms.

I agree that given current homelessness fares should not be elimated, but they also shouldn’t be raised given current crappy service, My understanding is that more people are schedule sensitive and fare elastic. If the buses and trains ran frequently and reliably, more people would ride regardless of fare. Reliable transit shouldn’t require looking at a printed or online schedule, the service should be frequent enough that you can show up at a stop and be confident that the next vehicle is only a few minutes away. Like Europe, Mexico or actually anywhere but USA, except for NY where you can use subway without worrying about schedule. In Response to Soren, transit this frequency benefits from density.

When funding public services comes up, some broad context helps. From Nomi Prins:

“The world’s 10 richest men more than doubled their fortunes from $700 billion to $1.5 trillion at a rate of $15,000 per second, or $1.3 billion a day during the first two years of a pandemic that has seen the incomes of 99% of humanity fall and over 160 million more people forced into poverty.” She adds a quote from Oxfam International executive director Gabriela Bucher that “if these 10 men were to lose 99.99% of their wealth tomorrow, they would still be richer than 99% of all the people on this planet.”

Free

Regular Service

Safe

Welcome to TriMet presented by Transit and Equity Activists, pick two items from the menu above.

Please see below for a coupon for air compressors at Home Depot. For $125 you can buy very cheap insurance in case Taylor’s buddies come by in the night and vandalize your vehicle because their naivete about how the world works makes them think that SUV drivers in Portland, OR are how climate change will be stopped. With this insurance you’ll be able to avoid the current transit environment that requires the use of Streetcar Rider Ambassadors to provide socks, water and other supplies to your fellow transit riders, ya know, just trying to get to work and all.

Have a great day, this is as good as it gets.

I once did a research project on the “death spiral” experienced by Portland’s private transit operators back in the 50s and 60s. Essentially they were expected to cover all their costs through fares, and they kept raising fares, then losing riders, then raising fares, and losing more riders, until they were an expensive service that no one wanted to ride. The modern system, in which fares are low and the vast majority of operating costs are subsidized through general taxation, is the only sustainable way to run a transit system. By raising fares, TriMet is going down the same road that has been shown to be counter-productive. The TriMet Board should be going to the state legislature to request more funding by raising the payroll tax or by other means, rather than relying on fare increases.