“Use your voice… to not support expanding roadway capacity for private vehicles.”

— Advisory Committee on Sustainability & Innovation report

A new report created by the Multnomah County Advisory Committee on Sustainability & Innovation (ACSI) did not mince words on the position elected officials need to take on transportation: No new road capacity should be created or given to people who drive cars and trucks.

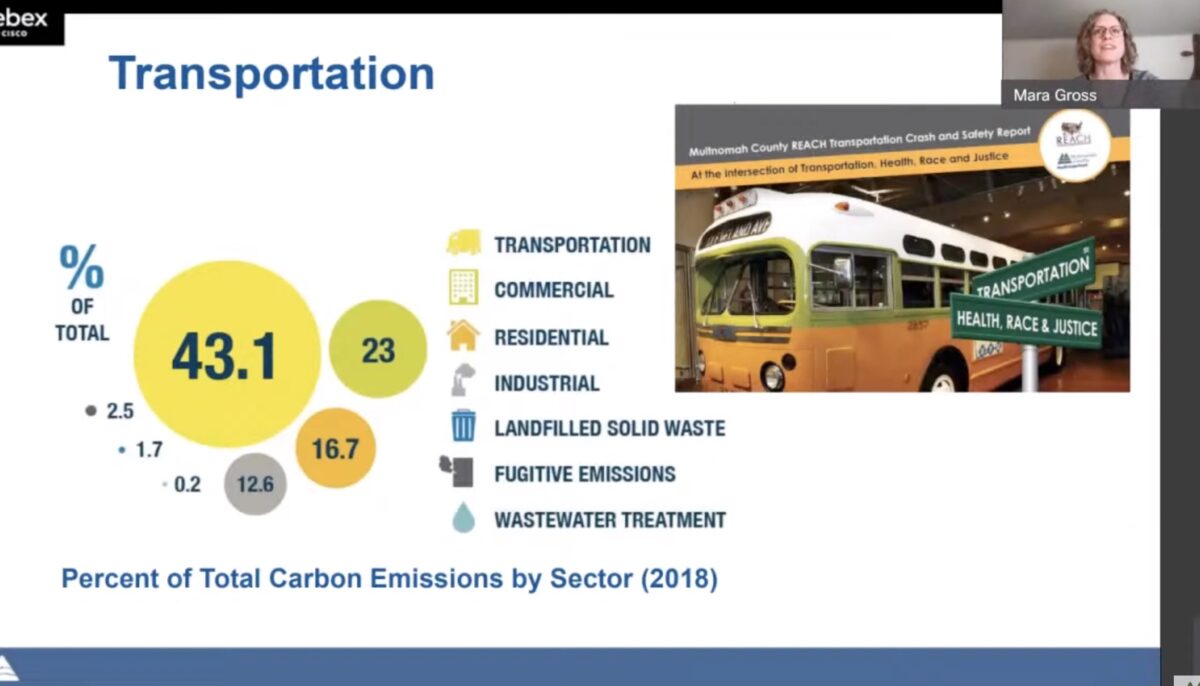

That message was delivered Tuesday to the Board of Commissioners via a new report that outlines how Multnomah County should address the climate change crisis. The transportation sector is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the County, so it rightfully played a prominent role in the report.

“Because the climate situation has fundamentally changed, our response to it must also fundamentally change,” wrote committee members.

The ACSI report came just days after the latest U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report was released. That report said local governments should mitigate climate change impacts, “through the provision of less car-dependent transport infrastructure… including protected pedestrian and bike pathways.”

The ASCI committee report strikes a similar tone.

Advertisement

It urges County leaders to spend new federal transportation funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in a way that prioritizes, “projects that provide reliable, affordable, and climate smart transportation options.” Going further, they want commissioners to speak up at regional decision-making bodies like Metro’s Joint Policy Advisory Committee on Transportation and ODOT’s Region 1 Advisory Committee on Transportation. “Use your voice,” the report says, “to not support expanding roadway capacity for private vehicles, e.g. the Interstate Bridge Project and Rose Quarter Project.”

The report also urged the County to do continue their work to tie transportation decisions to public health — especially as it relates to impacts on Black people, Native Americans, and other communities of color that are hardest hit by our current system. ASCI members want more in-depth health impact studies of regional freeway projects that would model emissions and toxic air pollution to vulnerable residents.

The recommendations in this report will loom large in coming months as elected officials throughout the region are asked to vote on a Locally Preferred Alternative for the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project, an expansion of I-5 between Portland and Vancouver. One source tells us an up-or-down vote on the LPA (a federally required step to endorse a general design concept) could happen as early as this June.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Pretty clear message: the science demands you don’t bend to the political pressure of the highway expansion lobby.

Skeptical it will be listened to. Lots of good rhetoric and bad votes will follow.

Until we have a functional transit system or viable alternatives what are working folks expected to do? The City has been trying for 40-50 years to get people out of their cars and have utterly failed. Maybe they should fire their traffic engineers/planners and get some new blood.

I know, it’ll never happen.

It would probably be more productive to reduce the amount of work being consulted and hire more people at the City/State. Most of the time Agency staff is so busy keeping up with the workload there is little time for innovation.

The engineers are simply applying the policies from adopted plans and the specifications required in adopted county and city codes. The problem is not with the engineers and planners, it is the law (code and policies) adopted by elected officials. The elected officials adopted these laws and policies in response to the demands of the voters.

Do you think that engineers and planners can simply make changes to the transportation system, such as arbitrarily changing speed limits or putting in new stop signs or speed bumps, at their discretion or based on their judgement?

If you care to look, you will find a high percentage of committed commuter cyclists among this region’s planners and engineers. They are really trying to do the right thing (defined by what WE want), but are constrained by the agency policies and the elected officials who set the priorities.

The idea that Portland, a city that produces little and consumes like a drunken sailor, should base its emission targets on the “production” metrics used in the above report is pure bull feces.

Don’t believe me?

Please see Section 2.6 of the UN IPCC AR6 full draft that indicates how urbanization is a leading driver of GHG emissions. And see Chapter 8 which discusses what cities should do to limit their disproportionate contribution to the climate crisis (stop consuming so much and so wastefully).

https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FinalDraft_FullReport.pdf

That’s incorrect. Urban emissions are increasing as more people especially in developing countries move to cities, but according to the report, cities generally have lower emissions: “For most regions, per capita urban emissions are lower than per capita national emissions. (IPCC, p. 8-4).

On solutions, here’s a key recommendation by the IPCC regarding land use and transportation: (IPCC, p. 8-6):

“Integrated spatial planning to achieve compact and resource-efficient urban growth through co- location of higher residential and job densities, mixed land use, and transit-oriented development could reduce GHG emissions between 23-26% by 2050 compared to the business-as-usual scenario (robust evidence, high agreement, very high confidence).

Compact cities with shortened distances between housing and jobs, and interventions that support a modal shift away from private motor vehicles towards walking, cycling, and low-emissions shared and public transportation, passive energy comfort in buildings, and urban green infrastructure can deliver significant public health benefits and have lower GHG emissions.”

Thank you for commenting, Mara.

Of course cities have lower per-capita “production”-based emissions given that production has shifted away from cities and towards ex-urban areas and developing nations (globalization). My comment addressed consumption-based emissions of affluent people living in cities so your response is a complete non-sequitur. Although my comment was focused on Portland’s current emissions, it’s interesting that you wrote “Urban emissions are increasing as more people especially in developing countries move to cities”. This is my entire point. The culture of hyperconsumption associated with urbanization is a major source of increasing emissions. Cities are associated with the highest levels of consumption-based emissions and this should not be ignored just because it’s inconvenient to urban residents (including climate organizers).

Developed countries tend to be net CO2 emission importers, whereas developing countries tend 2 to be net emission exporters (high confidence). Net CO2 emission transfers from developing to 3 developed countries via global supply chains have decreased between 2006 and 2016. Between 2004 4 and 2011, CO2 emission embodied in trade between developing countries have more than doubled (from 5 0.47 to 1.1 Gt) with the centre of trade activities shifting from Europe to Asia. {2.3.4, Figure 2.15}

Globally, households with income in the top 10% [the majority of Portland residents] contribute about 36-45% of global GHG 18 emissions (robust evidence, medium agreement).About two thirds of the top 10% live in developed 19 countries and one third in other economies. The lifestyle consumption emissions of the middle income 20 and poorest citizens in emerging economies are between 5-50 times below their counterparts in high21 income countries (medium confidence).

Please point to where I disputed any of this in my comment.

As the recent IPCC AR6 release makes clear, demand-side reform is essential for systemic decarbonization and this requires a move away from Portland’s consumption-based economy to one that emphasizes a plant-based diet, re-use, and services (as opposed to widgets). Keeping it in the ground is no where enough.

Well, at least now I know that your opinions can be discounted altogether, now. An anti-urbanist housing justice “advocate”? I suppose now I have seen everything.

I’m hardly opposed to urban density so please stop putting words in my mouth, Luke.

It’s my experience that market urbanists often discount inconvenient facts that require non-market (non-capitalist) solutions.

For example:

New Research Shows How Urban Consumption Drives Global Emissions

https://www.c40.org/news/new-research-shows-how-urban-consumption-drives-global-emissions/

The reason urban consumption is so high is because “urban” is where the people are. You have to be very ignorant to not read into the word “urban” as it’s historically been intended–racist, antifeminist, and classist. I don’t think you’ll find any urbanist who’s opposed to the various things we could do to reduce urban consumption emissions–electrified mass transit and cycling, mass timber vs. concrete construction, dramatic reduction in, e.g., food and clothing waste. Using the framing that you are–that climate change is a problem of urban consumption–is simply fuel on that fire, and leads eventually into ecofascism.

(You’d do well to learn, too, that markets and capitalism are not synonymous. In fact, one of the most egregious uses of state power is inherently capitalist–the protection of private property.)

This circular reasoning is a good example of the cognitive dissonance of market urbanism.

Please look at the Venn diagram that I posted and think about it for a moment before commenting.

BTW, the last time Portland bothered to inventory consumption emissions the results generated a similar venn diagram. Of course, metro Portland’s last annual inventory of climate emissions was for year 2011 which only illustrates how much embedded climate science denial exists in so-called progressive cities.

True. And my icon shows I’m hardly an opponent of market socialism.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fabian_Society#/media/File:Fabian_Society_coat_of_arms.svg

However, the speculative housing market that WIMBYs* think will somehow reform itself is thoroughly capitalist in the worst possible ways.

*Wall Street in my Backyard

The claim that climate change is “a” problem of urban hyperconsumption is your thoroughly ridiculous strawman.

The C40 coalition (which included Portland) noted that urban consumption contributes to the climate crisis and must be mitigated. The C40 coalition’s work suggests* that up to ~40% of total emissions are a result of urban consumption.

Your opposition to the UN IPCC climate science consensus on demand-side emissions is noted as is your suggestion that tackling demand-side emissions is “ecofascism”.

Randian capitalists always view any kind of attack on Fordism (which has imperialist and deeply racist origins) as “fascism” or “communism” or whatever derogatory label is in vogue among the Rand crowd.

FWIW, I believe tackling the over-consumption of colonial/rich nations (Fordism) can result in an improved quality of life for both people in developed worlds and in developing regions. A good example of this is the fact that some democratic developed nations with lower per capita incomes and consumption are widely believed to have a higher per capita quality of life than that in the USA.

*not a wishy washy word in science

I’m not arguing that per-capita carbon emissions couldn’t be lower in cities, nor that to address them is inherently fascist.

However, a lot of the historical focus on demand (consumption) side emissions has tended to ask a disproportionate amount of sacrifice from those who are already contributing less to the problem. That’s one reason I’m sickened by the so-called progressive environmentalists in a place like Portland who think, just because they hike and have Sierra Club stickers on the back of their Subaru, they’re not part of the problem. I’m sure I’m not saying anything new to you that population control (not even via sex education and reproductive rights) is the ecofascist’s favorite canard; addressing the hyperconsumption of rural elites–to say nothing of the misbegotten thing that is the McMansion’d, two-SUV’d suburb–is conveniently overlooked.

And it’s neither circular reasoning nor cognitive dissonance to say “urban is where the people are”, it’s a tautology, and evinces the fact that saying “urban consumption emissions are the problem” isn’t saying much at all. My contention is that focusing on reducing urban emissions, as opposed to increasing urbanism and doing it right (i.e., not American-style) is a more pressing issue, when the singular leading cause of American carbon emissions–to say nothing of the conflict we spread everywhere we get our oil and battery materials from–is our car-dependent suburbia.

I’m afraid we’re just going to be talking past each other if we say anything else.

Most people in Oregon live in cities so the idea that we can just pretend that more urbanism is good enough is a counterfactual. I should note that my list of “policies” in a post below would make life as usual impossible in suburbs so I’m hardly ignoring rich people in suburbs.

I should also note that there is an emerging literature that the optimal size at which dense cities reduce GHG emissions may be on smaller end of things. This was also noted in the recent IPCC release.

For example, a recent publication suggest that optimal reductions in GHG emissions have an unexpected relationship to urban area size (when held at constant high density):

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-11184-y

PS: I personally prefer to live in large dense cities (e.g. not Portland) so this emerging literature is an example of how climate science may cause me to rethink about my preferences.

I would argue, in fact, that most people in Oregon don’t live in cities; they live in suburbs. Actually dense, urban Portland doesn’t extend much outside of downtown, at all. Looking at and going to cities in less consumptive parts of the world should show you that most of Portland–and most of basically every American city other than NYC–is “urban” only in the U.S. census data sense of the word. It’s one of the reasons our urban consumption emissions are so large, especially compared to those of other countries’ large cities.

You should note, too, that in no scenario cited in that paper do cities’ return on growth turn into net positive CO2 emissions. Even in their large city scenarios, the emissions increase per population increase is less than a one-to-one. Demographic transition may, in the short term, negate the need for perpetually growing cities, but large, dense, low-or-no-car cities are the way of the future, no matter just how large those cities need get to accomodate most of humanity in them.

Suburbs and car centrism need to die, before they kill the planet and take the lives of billions of climate refugees with it.

It’s going to be interesting to see how “YIMBYs” accomplish this under actually existing capitalism without being classist and racist.

I personally am OK with a large increase in density in Portland proper and smaller urban centers in the Portland metro area regardless of whether some were “suburbs” once.

How would you suggest we lower our consumption based emissions, from a county policy standpoint?

Anecdotally, what I’ve observed is that how much people buy is proportional to the size of their living space. A person in small apartment owns less than someone in a 4,000 sq ft house. So I could see how higher density, smaller units could push consumption down.

Nevertheless, if you own a laptop, cell phone, fitbit, and eat a bunch of meat and drink bottled water, you are a big consumer.

This is a good thread, thank you everyone!

Read the IPCC report or a summary from a science-centered site.

https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FinalDraft_Chapter05.pdf

https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FinalDraft_Chapter07.pdf

Summaries with excerpts from a science-centric site:

https://www.carbonbrief.org/in-depth-qa-the-ipccs-sixth-assessment-on-how-to-tackle-climate-change#land

Thank you for the links. I was more looking for your words though.

I appreciate your, for this space, iconoclastic viewpoints. And I was asking if you had any specific policy suggestions for the county on how we can reduce consumption based emissions.

How do we reduce consumption? And/or consume more efficiently?

Build more energy efficient housing? Reduce meat consumption? Reduce VMT? Reduce outsourced consumer goods related emissions? If these are reasonable goals, how do we achieve them from a policy perspective?

I try very hard not to talk about policy in my “own words” when it comes to the climate crisis so the policies I would like to see implemented are just rewordings of the IPCC scientific consensus and also informed by the scientific publications I’ve read.

In no particular order:

1. Some of the lowest hanging fruit would be to conserve energy by switching to energy efficient electric heating/cooling systems or appliances and incentivize (mandate) energy efficiency infrastructure, such as, high-quality insulation/windows. This is already becoming the default in other less oligarchical developed nations.

2. Creation of policy and strong incentives/disincentives that cajole Portlanders to sharply reduce their consumption of meat, dairy, and rice (or switch to dryland rice). This would have an immense impact on agriculture-associated consumption-based emissions, most of which occur outside of urban areas. (Most Portlanders don’t realize that the US imports an awful lot beef grown on clear cut land in Brazil, for example.) I personally would advocate for taxes on high-embedded carbon foods that would be used to subsidize better food choices and access to nutrition. (In the long-term we should turn to technology that dramatically reduces the land footprint of our food growing systems so that more land can be used for accelerated carbon capture.)

3. A somewhat more difficult set of policies would be to disincentivize the absurdly high levels of goods consumption (electronics, clothing, appliances, other stuff etc) in Portland and other very-high-income cities. A VAT-like system that taxes the embedded carbon of imported/shipped goods is one mechanism (European nations are pursuing this). Another mechanism would be to regulate and/or disincentivize rapid “warehouse to door” delivery of online goods. The negative externalities of online shopping and hypermarkets could also be mitigated via anti-trust actions by government. Cities like Portland could also disincentivize “hypermarkets” and disincentivize rapid warehouse-to-door deliveries with local laws.

4. Recycling in Portland and the USA has seen steep declines as a result of a nation-wide move towards mixed recycling and a societal de-emphasis of conservation. For example, much of Portland’s plastic recycling has gone to the landfill in recent years and we still use an awful lot of disposable plastic that has no recycling market (e.g. anything above 3). Governments should ban disposable and non-readily recycled materials. We need a system that incentivizes consumers to recycle and manufacturers to create recycling systems. For example industry should be charged steep fees if their products are not recycled and consumers should be charged bottle bill-like-fees for most items that do not have long life-spans (this should include electronic items).

5. Right to repair, right to receive “updates”, government mandated energy efficiency, and government-mandated longevity standards for all consumables, including electronics. Ideally we would create a system where items could be easily repaired by consumers- see the framework laptop for one example: https://frame.work/.

6. Existing buildings should be upgraded to low- or zero-carbon standards via a mix of government-based incentives, credits, and regulations. All new buildings should have to conform to government-mandated low or zero-carbon standards. (Existing low- or zero-carbon commercial certifications are unregulated and are often nothing more than greenwashing.)

7. The cost of driving low-occupancy vehicles in urban areas should be dramatically-increased in a manner that is sensitive to deeply unequal access to non-automobile transportation options. We should also ban or sharply limit use of low-occupancy vehicles in large swathes of dense urban centers (with equitable access for people who live in less dense areas — there are many ways to do this). I am personally agnostic about how de-automobilization happens and there are definitely scenarios where there isn’t much of an increase in people riding bikes.

8. All transportation should be rapidly electrified — none of this waiting for better BEV bullshit when it comes to mass transit. Trains can be electrified now — and so can most urban bus lines. Transportation that remains carbon intensive should be strongly disincentivized/regulated (e.g. air travel).

Note: I intentionally did not discuss decarbonizing energy generation because we all know what needs to happen – renewables, storage, and nuclear only as a transition to a decarbonized grid. (I don’t think a rapid transition is possible under the current capitalist utility system in the USA.)

Thank you for taking the time to write all that out, Soren.

I’m going to add a link to an excellent and engaging NYT Opinion video titled Meet the People Getting Paid to Kill Our Planet. It is an exposé of big Ag which centers on the carbon footprint of our food choices. As Cory Booker says at the beginning of the video, “I am very frustrated that the incredible climate movement in America doesn’t talk enough about food.”

Right to Repair is high on my list of frustrations.

I could also have added more about waste systems, medical systems (which are incredibly carbon intensive in the USA), and land use/AFOLU but the above were what came to mind.

One of the things that really annoys me is that climate activists often talk exclusively about the fossil fuel industry when it comes to methane even though ~70% of methane emissions are biogenic. Agriculture is widely believed to be the major culprit for the sharp increase in methane emissions but gets almost no attention from USAnian climate movements. This is absurd given that several studies have suggested* that we could entirely eliminate fossil fuels and still see >2 C only from biogenic emissions.

*This is not a wishy washy term in science.

Yeah, if you think I’m going to take 1 1/2 one way trip to work on TriMeth, you are mistaken. Besides having someone threaten to slit my throat on a bus ride, my coworker watched a guy wipe his backside, toss the paper on the ground & then get on the train… no thanks. I’ll take my car.

Yeah, if you think I’m going to have to spend my time focused on driving instead of working or relaxing, spend $9,000 a year just to travel a few miles, be stressed out by traffic, and be more likely to get in a crash and die or kill someone than in another mode, you’re mistaken. Besides having someone threaten to run a 4,000 pound object into me, my coworker watched a guy destroy the planet just to get places… no thanks. I’ll take transit.

No thanks, I’ll take my bike, or just stay home.

Comment of the week?

Great post. Transportation is indeed where the focus needs to be.

This is old news. America’s energy sector still needs to be completely decarbonized, but the Obama-era switch from coal to natural gas for a lot of our baseload has helped to take some of the pressure to change our power generation. Much, much harder to improve will be our transportation sector. Americans still buy cars that are too big, and most still have no idea what a hybrid car is, and think that EVs are impractical and/or expensive.

And transit? Most of it is poorly-run, our wasteful land use patterns are painfully mismatched to it, it suffers a disproportionate image problem, and no one seems to see any issue with the situation, as a whole. I’ve talked with my coworkers about why I feel bad for ever driving my hybrid car the 3 miles to work (I have about a half-dozen times in the year and a half I’ve worked where I do), and they’re all like, “no one cares”. The world’s burning, and the cohort with the most power to do anything about it doesn’t give a damn.

If freeways get congested capacity goes way down.

If metered onramps let fewer cars onto the freeway, to prevent congestion, then freeway capacity would go up.

You would need a lot of computer modeling (and more sensors, more metered onramps,…?)to evaluate this.

A lot cheaper than building more lanes. You might avoid the problem that more lanes just result in more traffic until it gets congested, so in the end you don’t achieve your goal.