(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

Story by BikePortland Contributor Catie Gould

On May 17th, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) issued a press release to announce a reconfiguration of SW Madison Street aimed at faster bus service. “The upgrade of SW Madison is the first Central City in Motion project to be implemented, just six months after the plan was passed by Portland City Council,” the press release touted. Five days later it was done.

But for a handful of transportation advocates, the work began two years earlier. Today we’re peeling back the curtain to share what went on behind the scenes.

The summer of 2017 was bad for traffic. From April to October the Morrison Bridge, which carries 50,000 vehicles a day, closed access to downtown through the summer for construction. Less than a week into the closure, the Oregonian reported, “Much of the morning traffic has shifted to the Hawthorne Bridge, which has been clogged from about 7 to 10 [a.m.] for most of the week.”

On May 4th of that year, local lawyer and transportation advocate Alan Kessler posted a video of the backup on Twitter:

It is time for @trimet and @MultCoBridges to open the outer lane on Hawthorne for transit only. This is utterly absurd. pic.twitter.com/sQ8lwqazkb

— Alan Kessler (@alankesslr) May 4, 2017

One week later, BikePortland covered the story and linked to a meet-up of activists who wanted to work on bus priority lanes. That’s how Portland Bus Lane Project started.

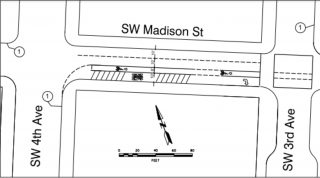

By August, Bus Lane Project volunteers were making an official effort to pilot a bus-only lane on SW Madison with another all-volunteer, grassroots group of transportation reformers, Better Block PDX. Better Block works with transportation and planning students at Portland State University (PSU) to develop traffic control plans (required for temporary road closures) and for pop-up projects that are officially permitted by the City of Portland. Better Block are the folks who brought us projects like Better Naito, Better Broadway, and the Ankeny Alley/SW 3rd Plaza project. The program is so well respected at PSU that it was officially added to the curriculum this spring.

The PSU students worked on concepts for SW Madison with Better Block through the winter, and by early April were discussing designs with TriMet and PBOT. On our end, as fledgling all-volunteer groups sometimes go, several people who kicked-off the project had moved on to other jobs or commitments, and we put out an internal call for more help. In the end, there were five volunteers who stepped up to see the project through to the finish line. I was one of them.

“Allowing PBOT to dictate that right turns must be allowed onto 3rd and 1st means we have allowed them to kill the project.”

— Marsha Hanchrow, Portland Bus Lane Project volunteer

The new Bus Lane Project leadership had immediate friction with the proposed design. “Why would we put bikes in between buses and traffic?” I asked at a meeting, worried about the reaction from BikeLoudPDX, another activist group I volunteer with. We sent in three different cross-sections that moved the bikes farther from moving vehicle traffic for consideration.

Routing the bike lane behind the bus stop would be more comfortable for people on bikes, but we had no examples of a temporary bus island small enough to fit that would maintain ADA access. My largest concern however, was that in the middle segment of our project — from SW 5th to SW 1st Avenue — there was a shared right-turn lane for drivers onto SW 3rd Avenue that allowed them to re-enter the protected bike and bus space.

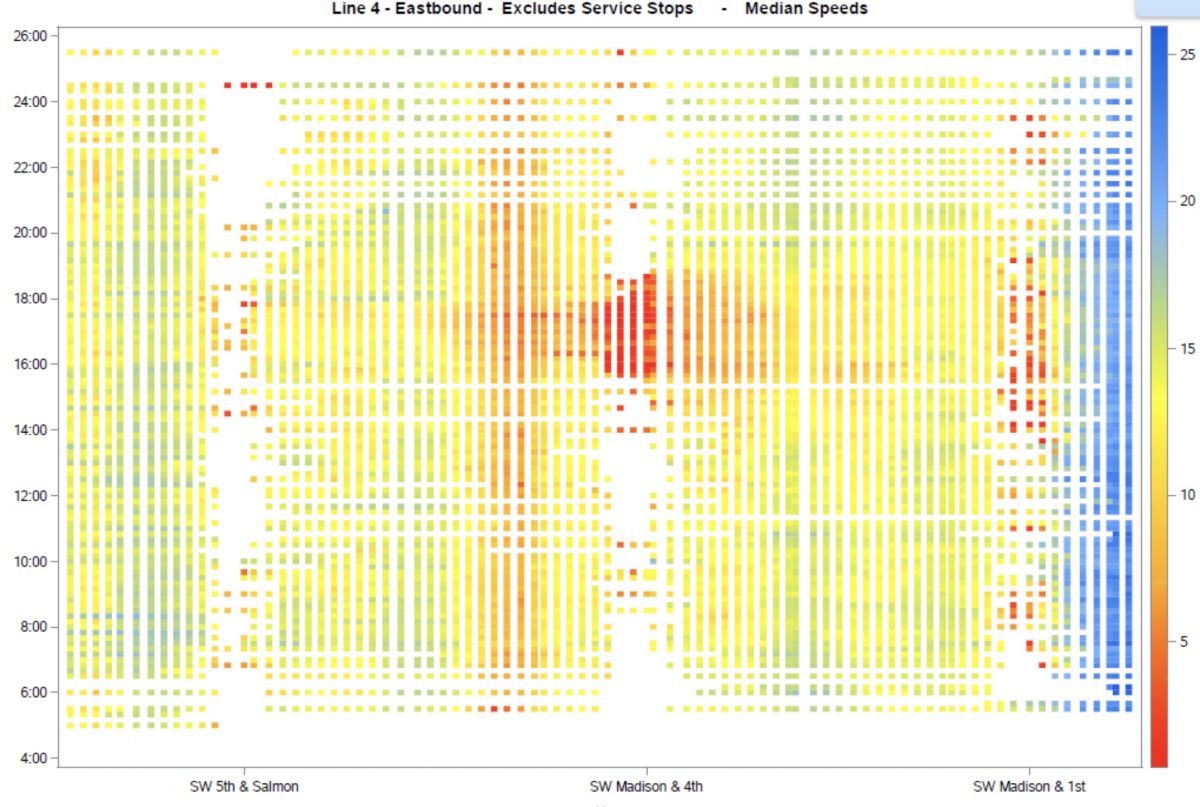

“The more I look at what we’re now presented with, the less I want to be involved,” Bus Lane Project volunteer Marsha Hanchrow wrote via email after seeing the design. “For me, allowing PBOT to dictate that right turns must be allowed onto 3rd and 1st means we have allowed them to kill the project.” We scrambled to find data to bolster our case that shared right-turn lanes would slow the bus down. TriMet data showed backups throughout the day at SW 1st Avenue, which had a shared turn lane.

Advertisement

PBOT didn’t budge on the right turns, citing access to a parking garage nearby as the reason. The death of Kathryn Rickson at the wheels of a right-turning truck driver at this intersection was brought up; but to no avail. This remained a major sticking point throughout the process.

Swapping a general travel lane for a parking lane would give us two extra feet of road space that we could use for a better protected bike lane.

At the same time, we researched bus lane projects in other cities as guides and found one thing in common: city-staffed implementation. Most of our meetings with staff were over the phone, and once written down, our to-do list grew quickly as we e-mailed the rest of the team what was expected of us. As a start, we needed liability insurance, an estimated $10,000 for materials and sign installations, and a commitment for around-the-clock response if something needed attention. “We didn’t have any money as a group at all,” recalled Sam Fader from the Bus Lane Project, “Honestly, I don’t know if anybody knew exactly what was needed, even PBOT. It was kind of new territory for everyone.”

Despite these concerns, we pressed forward and looked for funding. We applied for a community grant, and PBOT offered that it could be funded through an Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT) Traffic Mitigation fund for the I-84 ramp closure in August. “It was a glimmer of hope,” Paul Leitman of the Bus Lane recalled about the funding opportunity.

But even if the funding came through there were still key questions that needed to be answered if we wanted to finalize the implementation plan. Chief among them: the Portland Police Bureau (PPB) had not yet agreed to move their designated parking spaces that spanned from SW 4th to SW 2nd.

After meeting with the PPB to explain the project, they denied our request, so we escalated the issue with PBOT. Our design assumed the police vehicles would be relocated, but we continued to create sketches that included the parking as a backup. Swapping a general travel lane for a parking lane would give us two extra feet of road space that we could use for a better protected bike lane.

Aside from the design, we were being asked to temporarily cover the green bike lanes to prevent confusion. In the past, Better Block had used duct tape to create crosswalk lines, but re-striping an entire lane with heavy bus traffic had never been done before. Chalk paint also had a weather element we weren’t sure how to plan for. A three-day bus lane trial in Boston had used cones, and Toronto’s King Street pilot used jersey barriers to block lanes. Neither of those solutions appealed to PBOT.

The financial and liability requirements required from volunteers severely limits Portland’s ability to do more of them.

We put our concerns about material choices and the right turn on SW 3rd Avenue in writing in early May of 2018. The PSU semester was wrapping up and as the planning students working on the project submitted a final report, our window to change the official traffic control plans to a different design vanished before our eyes. Overwhelmed and unsure of our capacity to pull it off safely, we officially terminated our commitment to implement the project ourselves a few weeks later, still hopeful that the funding would come through for PBOT to do it themselves.

In June we received notice that the ODOT funding didn’t come through, so the project went on the list as one of the possible Central City in Motion (CCIM) projects. We didn’t hear anything else about it until PBOT asked us for a quote for their press release nearly a year later.

“Although Bus Lane and Better Block PDX did not implement Better Madison, it was still a complete success. Those conversations are what led to such a fast implementation,” Ryan Hashagen of Better Block told me over the phone. “You should be taking a victory lap.”

SW Madison still brings up mixed feelings for me. It’s clear these pilots push projects forward before PBOT would otherwise implement them; but the hundreds of hours of time spent collectively between staff and volunteers on these four blocks showed a clear disconnect between our desire to move fast and follow the same design standards as permanent capital projects. The financial and liability requirements required from volunteers severely limits Portland’s ability to do more of them.

That is what makes me so excited for Commissioner Chloe Eudaly’s bus lane projects. With only eighteen months before implementation, it will be necessary for PBOT to evaluate their own processes for how we implement pilots and hopefully set the stage for many more to come.

— Catie Gould

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Credit where credit is due. Thank you, Catie.

It’s great except for the bike lane is on the wrong side. And it’s for brave riders only.

It’s a little confusing, but the bike lane is intended only for passing stopped busses. Otherwise, bicyclists are free to take the entire lane.

I agree, the times I’ve wanted to pass through here I need to go on the right, which makes me uneasy. That and the road surface in the bus lane is absolutely awful, so I’ve mostly given up on passing people through here, just a bummer when it makes me miss the lights.

A dedicated bus lane here would be a huge and necessary improvement. IMO, this is the kind of facility that should be installed here.

The narrow “dashed” bike lane included in this “shared” facility is so absurdly dangerous that I would not be surprised to see it depress Hawthorne bridge cycling mode share. Even if the narrow striped lane is removed, these kinds of shared facilities are almost universally considered inappropriate for very high bus volume streets like SW Madison.

Don’t take my word for it — here is what NACTO has to say about these kinds of shared facilities:

“The shared bus-bike lane is not a high-comfort bike facility, nor is it appropriate at very high bus volumes.”

https://nacto.org/publication/transit-street-design-guide/transit-lanes-transitways/transit-lanes/shared-bus-bike-lane/

Soren, are you in favor of no bike lane at all on Madison? Or removing another auto lane to accommodate one? (I would vote for that!)

I think the real question for the future is if we build a bus lane, will we allow bikes & scooters to use it or penalize them? We have such a lack of high quality bike lanes on arterials I am confident that people will ride them regardless of the official rules.

At an absolute minimum I think the striped “buffer” lane should be removed so that people are not encouraged to ride within falling distance of the wheel well of 60 ton buses.

According to the google maps measurement tool, SW Madison is 36 feet wide. This is sufficient for two 9.5 foot travel lanes, a 5 foot green bike lane, and an 11 foot dedicated curbside bike lane. IMO, this is a far better option than the current facility. Because narrow bike lanes tend to discourage many from cycling, I personally favor creating an “enhanced” bike facility elsewhere. There are multiple options:

1. Salmon to 1st to bridge. (There is ample room for an “enhanced” bike lane on these more lightly-used streets.)

2. Columbia to waterfront path to bridge. (Higher traffic so an “enhanced bike lane would face more resistance from fans of cars/trucks).

3. Removal of a car lane on Madison would also work but I suspect that this is not politically feasible.

“will we allow bikes & scooters to use it or penalize them”

I think one way to handle this would be to have a policy of not penalizing people who use them while also not signing them as bike facilities.

If you zoom in to the traffic control plan, what was submitted last spring had 10 ft travel lanes, 10 ft bus lane, and 6ft bike lane.

“11 foot dedicated curbside bus lane”

“According to the google maps measurement tool, SW Madison is 36 feet wide. This is sufficient for two 9.5 foot travel lanes, a 5 foot green bike lane, and an 11 foot dedicated curbside bus lane. IMO, this is a far better option than the current facility.”

Aside from not coloring the bike lane green, how is what you are suggesting significantly different that what has been implemented?

All of what you are suggesting are narrower than federal standards, but slightly wider than federal minimums, for the posted speed limits.

david, there is no bike lane. there is a ridiculously narrow 4 foot striped buffer that is being used as a de facto bike lane by just about everyone. the tuff curb bollards make if even more narrow because people have a tendency to shy away from a barrier. what i have observed is that people ride dangerously close to moving buses during rush hour. moreover, because there are some slow riders i have routinely observed dangerous passing behavior.

and i will go out on a limb and predict that this facility alone will significantly decrease hawthorne bridge bike mode share. i avoid it now even though i road it every day for 19 years.

people:

you are sharing this lane with the bus. this is a single bus/bike lane. it is not a pair of lanes, one for each type of user.

you ride in line with the buses when they are traveling.

you are going downhill, so you will likely want to be going faster than the buses are traveling. you will easily keep up with the buses.

when the bus slows to pick up passengers, you pass the bus on the left, not the right.

if you pass the bus on the right, it will kill you by squeezing you into the sidewalk.

this is america; pass on the left. slower traffic keeps right.

the funny lane is to remind everyone on the road of this. that is why it is a dashed line instead of solid.

engineering manuals are for standard situations. applying them indiscriminately is how america murdered its central cities with gigantic surface parking lots and forbade building any good neighborhoods.

and this is about more than bicyclists, although upgrading from that stupid skinny old bike lane against the curb and covered with wet leaves into a massive multi-modal lane is great.

this is about allowing buses full of people to pass by single-occupancy cars stuck in traffic.

the only shame is that the lane does not extend all the way to the traffic mall, where gridlock freezes the bus through several light cycles during rush hour.

people: please read the first sentence of my original post.

“you are going downhill,”

much the facility is completely flat. and many riders will start from a stop at 3rd.

“engineering manuals are for standard situations. applying them indiscriminately is how america murdered its central cities with gigantic surface parking lots and forbade building any good neighborhoods.”

do you even know the history of NACTO? it was created by a few larger cities as a reaction to those ossified 1950s-style engineering manuals. this city would be a far better place to get around without a car/truck if Portland actually followed NACTO guidelines (but parking!!!).

the idea that we have to choose between a decent facility for people cycling and a dedicated bus lane here is nonsense as my post above illustrates. the fact that the city originally proposed a a 6 foot bike lane and a dedicated bike lane only further reinforces this fact. moreover, as i argued above, i believe the best solution is to get rid of the bike facility on Madison entirely. the fact that you are spinning this as opposition to a dedicated bus facility is an argument in bad faith.

I’d be cautious about applying NACTO guidelines to any and all situations. They are designed for “typical” cities, most of which have 500 to 800 foot blocks and wide streets, not Portland’s tiny 200 foot blocks with narrow right of way. By most city standards, what PBOT has implemented is very short, no more than 200 feet long for each section, and buses can’t really get up to the speeds needed to where they occupy more than their designated lane (fast buses need wider lanes unless their side-to-side movement is controlled by a rail or curb, a.k.a. BRT.) As for bicyclists’ comfort, what are their local alternatives? Riding on the sidewalk in downtown Portland is illegal; parallel streets one block over will be heading in the opposite direction; and no “interested but concerned” cyclist will be willing to move in car traffic (though I dare say many BP readers will.)

Given the Portland-specific constraints, I’d say this was the best of a series of bad options, including doing nothing. I congratulate everyone involved in creating a good politically-doable compromise that eventually was implemented. It is far far better than nothing.

Thank you, Catie. I am so grateful for the time that you spent teaching, goading, cajoling, negotiating, and advocating for these lanes!

I can’t wait to see the rest of your hard work come to fruition in the next couple years!