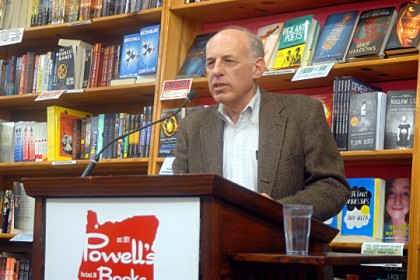

(Photo: Mark McClure)

Why does Portland require every new house to have a driveway big enough to fit two cars?

Why do we forbid most lots from having two separate dwelling structures unless one is 25 percent smaller than the other and has a roof with an identical slope?

Why do we ban second kitchens within a single home unless the owner essentially pinky-swears that only one household will be living in the building?

In a city where a chronic shortage of housing in walkable and bikeable areas has driven prices up and up, driving major changes in the culture, these aren’t trivial questions.

The most familiar answer to all of them is one of the most-used words in urban zoning: “compatibility.” But what exactly does that mean?

In his book Dead End, a political history of the suburbs, transit and biking advocate Ben Ross takes a close look at a vague word that shapes our cities one neighborhood association meeting at a time. From page 152:

Developers and nimbys, although everyday antagonists, share a common interest in the prestige of the neighborhood, and both use words as tools to that end. One party directs its linguistic creativity into salesmanship. Row houses turn into townhomes; garden apartments grow parked cars in the gardens; dead ends are translated into French as cul-de-sacs. The other side, hiding its aims from the world at large and often from itself, has a weakness for phrases whose meaning slips away when carefully examined. …

A tour of this vocabulary must begin with compatibility. The concept is at the heart of land-use regulation. In the narrow sense, incompatible uses are those that cannot coexist, like a smokehouse and a rest home for asthmatics. But the word has taken on a far broader meaning. …

The key to deciphering this word lies in a crucial difference between compatibility and similarity. If two things are similar, they are both similar to each other, but with compatibility it is otherwise. A house on a half-acre lot is compatible with surrounding apartment buildings, but the inverse does not follow. An apartment building is incompatible with houses that sit on half-acre lots.

Advertisement

Compatibility, in this sense, is euphemism. A compatible land use upholds the status of the neighborhood. An incompatible one lowers it. Rental apartments can be incompatible with a neighborhood that would accept the same building sold as condos. An apartment house and a ten-room mansion are both incompatible with an older subdivision of small expensive homes: the one because apartments are inferior to houses; the other because its yard, overshadowed by the structure, fails to manifest the conspicuous waste of land that gives such areas their special cachet.

The euphemism is so well established that the narrow meaning has begun to fall into disuse. Neighbors who object to loud noises or unpleasant odors just lay out the specifics; incompatible has come to mean “I don’t like it and I’m not explaining why.”

That’s from Ross’s chapter “The Language of Land Use.”

It’s a provocative take, though no harsher than the language we’ve heard in the last few years from some Portlanders discovering that their compatibility concerns won’t prevent new buildings in their neighborhood. And Ross, who lives and advocates in suburban Washington, D.C., is responding to slightly different dynamics than the ones we have in Portland, where everything is now shaped by the torrent of demand for homes in the parts of town best suited to low-car-life.

Still, it seems worth asking, every time we use the word “compatible” or allow someone else to do so, whether the values it implies are actually ours.

At least when it comes to driveways.

— The Real Estate Beat is a regular column. You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here, or read past installments here. This sponsorship has opened up and we’re looking for our next partner. If interested, please call Jonathan at (503) 706-8804.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

The roof slope must match requirement for adu’s is completely indefensible in my opinion. The structure is already required to be significantly smaller than the main house and tucked into the back yard, who cares if it has a slightly flater roof. If we really wanted people to build ADU’s we would relax some of these unnecessary requirements.

The city does not seem to enforce some of these ADU limitations like roof slope, arhitectural style etc. I think if the square footage and setbacks are okay, they will approve it.

I used my house as an ADU and buit a larger house in front of it a few years ago. The roof slope doesn’t match and neither does the architectural style, both of which are supposed to be required.

They told me that I could apply for a variance ($$$) and that it might or might not be approved, no guarantees.

The more I think about it the more frustrated this makes me actually. Building an ADU from scratch can easily be a 50-100k dollar investment. The idea that the city is winking at some people but not others around certain aspects of the code is frustrating, but not nearly as frustrating as it would be to complete the project only to have a hard-line inspector tell you that the pitch didn’t match so you needed to tear it down and start over. Loose and erratic enforcement is no way to oversee a building code.

“A house on a half-acre lot is compatible with surrounding apartment buildings, but the inverse does not follow. An apartment building is compatible with houses that sit on half-acre lots.”

Shouldn’t that be: “An apartment building is _not_ compatible with houses…”?

I stumbled over that one, too.

Yep, typo on my part. Fixed.

I’d love to see a study on how market pricing of housing, which is a significant factor in causing long single-occupant-vehicle commutes, affects energy use and climate change.

I’m not following. Can you elaborate?

I think they want to know how much damage a long commute is causing on the environment… people are forced to commute from suburbs because housing in the city is too expensive…

imagine how much cleaner our environment would be if those commutes disappeared because people could afford to live close to their jobs…

“imagine how much cleaner our environment would be if those commutes disappeared because people could afford to live close to their jobs…”

Well, sure, but the problem underlying the jobs-housing mismatch is a little more complicated than these houses are too expensive. I thought the trend has been for the majority of people to live *and* work in the suburbs, just not necessarily in the same one.

Too many (rich) people, too many square feet (demanded) per person, perennial cheap gas, land use laws like those Michael has highlighted, crummy legal and physical conditions for using bikes or feet to get places are just a few reasons I can think of for why we’re in this pickle.

That’s a viable point, but there are folks who want a larger lot in the suburbs (which can be less expensive) and don’t care about the impact their commute has on anything else. How to convince those folks that living closer to work for congestion or pollution reasons may be one hurdle that can’ be overcome. Some people just don’t seem to care.

And some suburbs are actually closer to where people work (Nike, Intel, etc.)

just charge them $20 / day to park their cars

Good discussion. From your article…”A tour of this vocabulary must begin with compatibility. The concept is at the heart of land-use regulation.” Actually it is not. Regulations (zoning ordinance) must be clear and objective (i.e. permitted or conditional uses). Form and massing can be regulated (setbacks, active frontages,etc.) but must be done with caution. “Compatibility” is discretionary and best defined and addresses through design guidelines and design review process. Where communities get in trouble is when they over-reach and try to regulate development ‘style’ that may be best addressed through a design review process.

Right, compatibility, as Don mentioned, can be sought through prescriptive zoning regulations and design standards. But “compatibility”, especially from a NIMBY perspective, seems to have more to do with the gut-level feeling that something just isn’t right about the design, look, size, use, and feel of a building. The new Renaissance Homes going up as infill or teardowns in N/NE/SE Portland, for example, are completely code-compliant but certainly tend to be larger and differently-styled than many of the century-old homes in the neighborhood. Though legally compatible, they might not feel viscerally compatible. It many or may not be entirely up to code changes to address such concerns.

Single-family homes rebuilt as single-family homes are contentious enough, to say nothing of single-family teardowns for townhomes, duplexes, or even multi-family. I’m encouraged that we do have an active infill and rebuild market in established neighborhoods (some houses weren’t meant to stand forever); developers haven’t quite fine-tuned their model to inner neighborhoods, as opposed to suburbs, so I’d expect growing pains as they and we in the community shape urban development.

That said, I think we all agree that more flexibility will be needed to meet our housing needs. This includes allowing development that may ruffle “compatibility” feathers regarding size, use, aesthetics, shared housing, ADUs, and the like.

For some neighborhoods, a prescriptive approach to regulating materials and quality of construction for ‘compatibility’ may be appropriate. Rather than regulating what is appropriate, I suggest that cities should regulate what is not appropriate. Design standards can be crafted that prohibit synthetic stucco, stone veneer, simulated divided lights… yet leave room for innovation and creativity.

None of this matters however if codes are developed in a vacuum. This ‘compatibility’ issue would occur less often if cities created great neighborhood plans that are in turn supported by regulations. For any number of reasons, most cities develop comprehensive plans and then craft one-size-fits-all zoning that does not consider specific neighborhood issues and conditions. I fear that PDX Planning Bureau is falling into this trap with our current mixed use zoning project.

Don, the concept of compatibility (or my least favorite term, “neighborhood character”) is a lot more common in land use than you imply.

You’re right that a lot of development rules are clear and objective, and if you can repeat the existing pattern, no problem. But if you have a building idea or a use that’s a little different from what’s on the ground, you usually get moved over to a discretionary process, where compatibility and character get used like a club. For example, if you want to open a daycare in a residential zone, or to not build that parking space Michael refers to, or have a flat roof on your ADU, you have to go through a process where you must show, among other things,

“The proposal will be compatible with adjacent residential developments based on characteristics such as the site size, building scale and style, setbacks, tree preservation, and landscaping” (Portland Zoning Code 33.815, similar language in 33.805)

Maybe it’s a good thing to have a check on development that is a little outside the norm. But it’s true that in this sense, rules can be highly discretionary and interpretative, and set up to enforce the status quo.

A good code is never discretionary. The key for discretionary review is a consistent design review process. No free-lancing by reviewers. This is one area that the City of Portland’s Design Codmmission far exceeds most cities.

In Woodstock ‘hood, neighbors defeat proposal at City Council using compatibility after losing at staff and Hearings Officer levels. Sole issue: whether width of two infill lots–33 and 32 feet instead of required 36 feet–were compatible with surrounding area.

https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bds/article/495638

Amanda Fritz cites this case as an example in her memo telling BDS staff they should use compatibility as a reason to reject more applications.

http://www.oregonlive.com/business/index.ssf/2015/02/under_amanda_fritz_portland_de.html

Michael, good questions.

I’d love to see one long list of all the small policy changes that could have a big impact on the housing problem.

“Why does Portland require every new house to have a driveway big enough to fit two cars?”

I’m either confused, or this isn’t actually true. The website you linked to shows a diagram with a required spot for car parking and another non-required (but allowed) spot for a second car.

Only one parking space is “required”, but the requirements for where it is located (at least ten feet down the driveway from the edge of the lot) mean that every driveway has the “optionally permitted non-required parking space”. I can’t figure out any way to comply with those requirements without ending up with enough space for two cars. Maybe on the properties that have a shared driveway between two houses that widens back out into parking spots behind the house?

I still don’t get it. Is Michael counting a garage as the “driveway?” When I get home I can post a picture of the recently built house next door to mine which definitely does not have a driveway long or wide enough for two cars. In fact, all of the new homes I’ve seen in NE Portland, though horrendously large, don’t have massive driveways.

Good question, David. Here’s how it works as far as I can tell: the actual code requirement is one parking space per dwelling. This can be fulfilled by either a garage or just a driveway. However, as the document I linked to shows, both the garage and the driveway’s “required parking space” are required to be set back far enough from the sidewalk and/or property line to fit a second car.

An alternative requirement would be to remove the setback, so you could have either the one driveway parking space or a garage that’s up against the sidewalk. Or we could require the setback only if there’s a garage. Or we could remove the minimum parking requirement altogether – which might actually be pretty space-efficient because fewer driveways mean more curbside parking spaces.

The required space in the driveway between the front of the building and sidewalk provides for several things. It allows you to out of the car to open the garage door and provides a space where a short-term visitor can park or pick-up/drop-off a resident. It annoys me no end when driveways are so short that motorists block the sidewalk with a vehicle.

That is the fault of the motorist, not the driveway. If it were designed for parking, they should call it a parkway.

Wait, are you now advocating for more free, curbside parking? Yikes.

Me? No, just trying to define the policy choices here and note that parking-lovers don’t see a net parking capacity gain unless driveways fit at least two cars, which I assume we can agree is more that a central Portland house should require.

Personally I’d rather have paid curbside parking on local/neighborhood streets than mandatory off-street parking. You don’t want bike lanes on most of those streets anyway, right? Proximity and affordability benefits, meanwhile, would be huge.

That condition was likely adopted to avoid snout houses, which were very popular back in the ’90s in the suburbs. Portlanders became very vocal and opposed snout houses, which feature, as their main design feature, a large garage oriented towards the street.

Snout houses:

http://www.nytimes.com/2000/04/20/garden/in-portland-houses-are-friendly-or-else.html

http://cityregionnationworld.blogspot.com/2012/01/ode-to-townhouse.html

the diagram seems to show that you only need to have a parking space that’s 10′ away from the sidewalk… however that means you have 10; of driveway to get to that parking space, so it’s essentially another half of a parking space….

10 feet of driveway + 18 feet of parking = 28 feet of parking…

I think the idea is to keep the front of the house clear for visibility… keeps you from breaking the law and stopping on the crosswalk in order to see cars coming down the street…

just about every parking garage in downtown has no setback and therefore every driver has to break ORS 811.550 section 4, although ORS 811.560 section 5 probably thinly exempts them…

Not totally related but since there is a post about housing/zoning here, and I just read this, here you go. Ignore, rip it apart, defend it, whatever.

Closer to my home in New York, I’ve found that upper-middle-class people are the chief culprits behind the gentrification wave that is driving many poor families out of close-in neighborhoods in Brooklyn, my hometown. Stephen Smith has done an excellent job of explaining the dynamic. Most affluent people would be just fine with living in condos in Manhattan if they could afford to do so. But rich Manhattanites fight new development with every fiber of their being, which forces slightly less rich people to move to Brooklyn. Here is where things get interesting. Early on, as gentrification first takes root, these new upper-middle-class arrivals root for development, particularly when it means things like a new Whole Foods and other amenities that make their neighborhoods seem less “sketchy.” Once they have their fancy grocery stores and their Pilates studios and whatever else it is that floats their boat, however, they sharply shift toward absolutely hating new development, as new development means having to share their new amenities with more newcomers. These new restrictions on supply mean that homeowners who arrived at the right time, before the drawbridge was raised, see their homes get more and more valuable. Landlords can charge higher and higher rents.* The neighborhood gets less and less “sketchy,” which is to say less diverse and less inclusive. How convenient.

Yep. That’s how gentrification works. Good for the people who own houses. Bad for the people who rent. Good for people who want to change the neighborhood to suit their preferences. Bad for the people who liked the existing culture of the neighborhood. Change is good for some and bad for others. I think the contentious part is that in our current legal system having lived in a place for all your life doesn’t grant you any special rights over someone who just moves in and that doesn’t “feel” fair.

If in “existing culture” you mean abandoned lots, run down houses, boarded up businesses, crime, etc. then yes it is bad for people who support that.

Don’t forget poor schools and no grocery stores.

Thanks, Huey Lewis. Do you have a link to some of Stephen Smith’s work on this subject?

Sorry for the slow delay. That’s from an article I was linked to on slate. The rest of the article had not much else to do with housing and development.

Slow *reply*. Gah.

It would seem, then, that the pressure should be on continuing to provide supply so housing remains affordable. You already see the range of people in a community– there are already people in Portland who have had enough. The thing is, I believe we should build until there is an oversupply. That way rents can come down to reasonable levels. That way, any push to add housing would actually be glut. Inclusionary zoning which focuses on rentals can help with this, too. We need a percentage of new rentals to have low and middle income stock.

You may well get your way with this jeg. Portland was affected with one of the tightest rental markets in the country. The result has been the massive build up of new apt. buildings we see across most quadrants by developers the last few years. Some think it won’t stop till there’s a massive oversupply and developers take it over a cliff – there may be early signs of that even now. We saw that with commercial/retail build out in the years leading to the recession. Even before the crash many were asking just who was going to occupy the endless strip centers etc.

But for apartments, in contrast to the idea that plentiful supply will keep prices low (understandable thinking) it appears despite the residential “boom” now, rents continue to rise. Perhaps conventional models of supply and demand break down here.

Or maybe our idea of what is “a lot” of new housing is much smaller than the number of housing units needed to actually decrease or significantly slow the increase of prices. In San Francisco, the City’s chief economist says that 100,000 new housing units would be needed to noticeably impact prices. That’s similar to the total number of housing units that have been built in San Francisco since the ’20s.

As I see it, the options are:

-Status quo (rapidly rising housing prices)

-Way more housing development

-Intense command & control regulatory measures (rent control, etc.), which, unfortunately, have strong and unwanted unintended consequences (e.g. rent control makes developers leery of building in a city)

It doesn’t help that all the new development tends to be high-end, high-rent apartments. Those that exist aren’t suddenly opened up to people that can’t afford them already, and the new ones are snatched up by new immigrants and new money, never allowing the rental market to lower.

Yes, and not building housing will totally solve that. The UGB isn’t moving because we value our ecosystem and don’t want to subsidize suburbs. Building up is the solution– adding housing stock is one way to stabilize rents. If you don’t build, the rents continue to skyrocket.

Yeah, but rents don’t increase as fast in older units without a very tight housing market. Once this new crop of apartment buildings start to age, they won’t stay at the top of the market.

Also, to call them “luxury” is a total joke. How many of them offer concierge or other “luxury” features? Almost none.

Early in my career, I worked in a planning job where I helped with some of the zoning interpretation and development review. I can tell you that it’s really complicated and can certainly become contentious.

I urge readers to click on some of the links Michael has provided, such as the first one on parking. Look at some of the things they are trying to accomplish, such as preventing your neighbor from parking his semi-trailer rig in his driveway.

You may not agree with some elements of the zoning code, but it was developed in a public process that involved lots of compromise.

The compromises represented by the zoning code involve tradeoffs such as those you have to make when selecting a new bike: weight/price; on-road/off-road; responsiveness/stability; hauling capacity/lightness, etc.

There are many in my neighborhood who want to make it an historic district to prevent what they see as monster house and excessive infill and or even to “protect” the style of housing. I’m opposed because I know it would have prevented me from changing the façade of my house by installing new windows that make the house more useful, comfortable, and energy efficient.

The zoning code involves lots of compromise and it’s extraordinarily difficult to foresee and adequately describe the clear and objective standards that need to be applied in all cases. That said, if any of you want to get involved, I’m certain opportunities will arise. The land use or transportation committees of your neighborhood group would be good places to start.

Actually, are you sure it would “prevent” you from doing it or just require a design review before you were allowed to proceed? That’s how they do it in Irvington, which received national historic status a few years ago. My understanding is that if you’re just planning to upgrade windows, etc., you shouldn’t encounter any resistance. A “façade change” might though, depending on what you had in mind. You do have to pay a review fee, which seems a bit onerous when you’re just changing windows and nothing else.

Thank you. A voice of sanity!

How can people get involved to make changes to these laws so they create the type of development that they want?

Perfect question to ask, Martin!!! Between the comprehensive plan, accessory structures code package, mixed use code update, and (probably forthcoming) review of neighborhood zoning issues, there are quite a few ‘trains going through the station’ that will guide development in Portland for years to come. I’ve posted some ideas on my blog (http://www.orangesplot.net/2014/04/24/new-ideas-to-meet-portlands-housing-needs/). But what we REALLY need is a more politically organized and coordinated voice from Portlanders who care about these issues. Perhaps some collaboration between Bike Portland, Coalition for a Livable Future, and Housing Land Advocates is in order… I’m trying to get that conversation started. Sounds like Bike Portland may be a great way to spread the word about ways to get involved.

gentrification is the exception, not the rule for urban neighborhoods. Check out Joe Cortright’s CityObservatory.org for more analysis.

Check out Governing magazine which is reporting that 58% of Portland’s tracts have gentrified since 2000. The exception? Hardly. It’s the design.

http://www.governing.com/gov-data/gentrification-in-cities-governing-report.html

Lenny, I read Cortright’s analysis and it seems valid on the national level but it also seems (per the Governing piece, among others) that in a few key cities, Portland and DC among them, rising prices really are leading to involuntary displacement, often of poor people of color. Seems to me that the bike-friendly neighborhoods in Portland that we spend most of our time writing about on BP are the exception you mention.

Seems like a catch 22 for this site: Many on here hate the idea of allowing free car storage in the public right of way (I think I fall into this camp when it makes sense), yet bristle at the idea of a requirement for off-street parking.

Not inconsistent. I strongly support permitting off-property parking and allowing development without parking space requirements.

Why is that a Catch-22? Cars cause untold problems, and *requiring* us to accommodate them either free in the public right of way or by statute on private property seems like a really foolish approach to take. The issue isn’t whether people will find a place to park their car(s) while they still have them, but whether our laws and rules should be built around the assumption that everyone has two of them.

“the assumption that everyone has two of them.”

Except that assumption by and large (even in Portland) is true for a majority of households in Portland.

In 2 worker households, less than 43% have 0-1 vehicle. (Less than 9% have no car).

http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk

So with that in mind, YES it makes sense to have rules that address cars that people own.

“YES it makes sense to have rules that address cars that people own.”

I’m o.k. agreeing to disagree. My interpretation of these kinds of clauses is that there is no reason whatsoever they should not also be used to steer things in the direction we know we need to head. One of these days (and I know you love to hear me say this, davemess) we’re going to have zero cars per 2-worker households. Why pretend this doesn’t concern us, or waiting until it is upon us to translate this insight into code requirements?

“It’s a great utopian idea that people will all ‘see the errors of their ways’ and give up their cars, but we all know that’s not going to be the case 100% (or even 50%?) of the time.”

But it isn’t, chiefly, going to be about changes in preferences; it is going to be about constraints. If you can’t afford to buy gas (I know that may seem fanciful today, but wait six-nine months) or driving has been drastically restricted, the car that everyone was counting on to always be there won’t be of much use.

“steer things in the direction we know we need to head”

And that’s the rub. WE all don’t agree on this. And many (based on the stats of a majority of) people don’t agree with you and your ideal goals.

And planning for a (somewhat unlikely) possibility in the future is not sound policy for dealing with today’s problems.

“And planning for a (somewhat unlikely) possibility in the future is not sound policy for dealing with today’s problems.”

I agree. But the unlikely possibility is that we will continue to ‘enjoy’ automobility, that the future will be an extrapolation of the past.

“many […] people don’t agree with you and your ideal goals.”

If we were committed to eliminating 70% of lung, trachea and bronchus cancers, the staggering public health costs of smoking, not to mention second hand smoke, would we consult smokers, or would we develop principled guidelines that reflected our best understanding of these relationships?

Seems to me it’s the free public parking that makes the on-site parking requirement necessary in the first place. If we’d already been charging a fair price for street parking in Richmond in 2009, a lot more of those apartment buildings would have been constructed with on-site parking because the car-owning tenants would actually be willing to pay their landlord to use it.

“Seems to me it’s the free public parking that makes the on-site parking requirement necessary in the first place”

Except regarding apartment buildings (as you mentioned) its actually the opposite. The city allows parking-free buildings because of free street parking.

So again, this comes back to my point that you have to give people a place to park (as most people still have cars). Either in the street (free or pay) or off street in driveways and garages. I agree that the city should be looking to go either way, and either focus on maintaining street parking (as they clearly seem to want to do), which may have a negative effect on bike infrastructure OR have building requirements for off street parking in houses and apartment buildings. Right now the city seems to be trying to do both.

It’s a great utopian idea that people will all “see the errors of their ways” and give up their cars, but we all know that’s not going to be the case 100% (or even 50%?) of the time.

Wait, there’s a difference between “Most people have cars and it would take some very strong incentives to get a large number of them to go car-free” and “you have to give people a place to park.” Emphasis on the “GIVE.” My problem with both the zoning regulations and free street parking is that they end up distributing the cost of parking evenly across people who use it heavily, people who use it lightly, and people who don’t need it at all.

Why shouldn’t there be options out there for people who want new homes in Portland, but don’t want/need a parking space? Why should people without cars, or with fewer cars (both populations tend to be poorer than average) pay for the maintenance of the copious pavement under our on-street parking? It just doesn’t seem fair, economic, or reasonable to me.

For that matter, why should people who always park off-street have to pay for the maintenance of the infrastructure for on-street parking? User fees seem like a home run to me here, am I missing something?

Yes. We live in a society where people have to pay for things that they might not use (libraries, foster care, fire, parks, schools, roads, bike infrastructure, buses, trains, animal control, etc.).

Society (and government funding) isn’t ala cart.

(and I don’t even have an issue with charging for street parking)

“Why shouldn’t there be options out there for people who want new homes in Portland, but don’t want/need a parking space?”

And that’s assuming that the occupant of the house you buy or rent will always remain car free and not have a use for off street parking. For most properties that seems unlikely. So a new owner buys the house and then they’re parking in the street.

“We live in a society where people have to pay for things that they might not use (libraries, foster care, fire, parks, schools, roads, bike infrastructure, buses, trains, animal control, etc.).

Society (and government funding) isn’t ala cart.”

Those comparisons of how we pay for public goods is a familiar reference when we’re talking about the Street Fee or onstreet parking. But I think the analogy is flawed. The list of public goods you enumerated above includes things that have, generally, stood the test of time. I think there’s pretty broad agreement that these are beneficial & contribute to the kind of society we want to live in.

But automobility is different. While for much of the Twentieth Century we assumed it to be a public good like these other things, we’ve now had enough time to discover that spending which is directed unilaterally toward accommodating cars (parking requirements like we’ve been discussing here), or paying for deterioration of our infrastructure that is due to our overreliance on cars and trucks (Street Fee)—is a dead end, is not a public good in the larger sense that these other functions are, is what we might call a public bad. The dozens of deleterious effects of automobility (blight, sprawl, isolation, carnage, climate change, oil wars, etc.) don’t inhere to the other public goods you list, nor do they inhere to other forms of transportation.

Good point, paying for something one doesn’t use is common and in many cases a good thing in government policy. But those things ought to have a genuine public policy justification that outweighs the cost to the non-users. The publicly-provided services you mentioned there have two main public-provision justifications that I don’t believe apply to free on-street parking –

1. Benefit to society at large (even those who don’t directly benefit): schools, libraries (educated population – much better for economy, also better able to participate in democracy), parks, bike infrastructure (health), buses, trains (less traffic), animal control (not bitten/harassed/annoyed by feral animals), fire (stops spread of large fires), foster care (not the primary motive, but better care for kids than being on the streets or in unsafe homes means lower safety net spending in future, less crime), roads (necessary for economy)

2. Moral imperative to provide for the less fortunate: most of the above, but particularly schools, foster care, libraries, parks

What is the public policy justification for free on-street parking? Some ideas:

*Difficulty of enforcing paid parking? (Not all that difficult, many cities have very successful paid parking permit enforcement)

*Benefit for the economy at large? (I don’t think so – although driving is indeed very important for the economy, what’s at stake here is the *additional* driving and parking enabled by free parking compared to paid permit parking, for example. The additional driving and parking might well be an economic negative for the city due to the low value to drivers of the trips – if the trips were high value, the drivers would be OK with paying for parking – the health costs of inactivity enabled by the additional driving, the additional air pollution, the additional money leaving the city to pay for fuel and vehicles, etc.)

*The bad feeling of making poor people pay for parking? (For one thing, poor people have fewer cars and driver less – and the city should just put in a low-income free permit eligibility program!)

This policy appears to me to be something that persists because it is popular because people think “Don’t take away my ‘free’ stuff!” (though in reality the “free” service extremely expensive to provide), not a because it has public benefits that outweighs the costs.

“(both populations tend to be poorer than average)”

While this may be true, I think it is more interesting to look at this, not from the perspective of the averages, but the other way around: In which income brackets do we find carfree households? Answer: in all of them. What percentage of homeowners do not own a car? In the census tracts in SE that I examined it was something like 6%.

Maybe someone can clarify this “required parking space” stuff. I recently bought a house that had essentially a gravel parking lot in front of it. Since I have no car, and therefore no use for a gravel parking lot, I have been removing the gravel and building the soil over my entire yard up to the front lot line. The idea is to plant the entire front yard with useful plants instead of having an empty, barren gravel parking lot.

Is this somehow disallowed or incompatible?

If you plan to stay in your house, and don’t tell the city about your plans to remove offstreet parking I can’t imagine you’ll encounter any resistance.

A chronic shortage of housing or a persistent longage of people?

Incompatible: The neighboring property owners have enough clout with the city to prevent new construction they don’t like.

Compatible: The property developer(s) have enough clout with the city to build whatever they want.

That is excessively polarized a view on the situation. Should we not build an allow rent to continue to skyrocket? We need to continue to build and make new rentals include low and middle income stock through inclusionary zoning.

Inclusionary Zoning is illegal in Oregon, thanks to the Oregon Legislature, some years back. On Portland’s legislative agenda is changing that. The Mixed Use Zones project of the city is trying to write incentives into the codes in these zones (all Commercial zones), i.e. if you include affordable units you get more FAR. It may result in the situation where if you include enough affordable units, you’ll actually be able to build to the height you were able to by right, before the code rewrite.

There is an exemption to the required parking space/driveway for housing sites (with < 30 units) within 500' of frequent transit service (a significant portion of the City, particularly for close-in neighborhoods). However, few of the homebuilders that could use the exemption do (orange splot is the most visible exception).

see Joe C’s response to Governing on CityObservatory.org

Cortright’s data on Portland shows census tracks with poverty rates above 30% increasing from 8 to 18 between 1970 and 2010. Population in poverty increasing from 7.6k to 23k.

For the better part of 50 years following WWII we dis-invested in our cities, throwing all the public and private money at the suburbs. That began to shift at the turn of the century, and we should be celebrating that. Yes, capitalism sucks and the rich need (for their own sake!) to pay more, but re-investing in cities has been one of the best things to happen here and elsewhere with the upside way outweighing the down side.

Depends on what you are defining as the “city”. I’m going to guess that most of the increase in the poverty rate is not in the areas that have gotten the most funding the last two decades.

If you rent, and your neighborhood takes off, and you want to stay put…its either pay more rent or downsize. If you own, its just sit back and watch your equity (and to some extent your taxes) grow. We need to make sure that low income home owners don’t get taken with “cash now!” offers, to make sure they can get loans to do necessary repairs, etc.

For renters, we need to build, build and build some more…no more vacant lots, no more parking lots on major transit lines, no more parking requirements that jack up rents.

“For renters, we need to build, build and build some more”

Why is it so hard to recognize the limitations of a supply-side focus? This is a recipe for disappointment. Accommodating growth does not lead anywhere automatically preferable. This willful and predictable skipping over the demand part of this situation is troubling. Most of us are not developers or people with vacant lots and deep pockets. But we are citizens who can advocate for policies that stop incentivizing in-migration, reward growth.

I prefer density to sprawl, too, and think what has happened on SE Division over the past few years has yielded some pretty pleasant places and spaces, but neither of these observations requires that we skip over the option of pushing back, of reining in growth.

Hey 9watts, could you give some ideas of policy options to limit population/etc. growth? My mind goes blank when thinking about feasible (local) ways to address this – take away the child tax credit? That’s both federal and a big lift. Make parents pay for public school? Would be hard to craft such a policy that wouldn’t be anti-equity. Financially or otherwise penalize in-migrants? Just feels like a policy that would seem unsavory to a majority of people because migration isn’t seen as a “sin.”

(I’m most interested in options that are aimed at population and in-migration, not those aimed at limiting development; we already have – at least some – policies aimed at limiting development 🙂 )

“Hey 9watts, could you give some ideas of policy options to limit population/etc. growth?”

Sure. Let me give it a shot. Right now we are spending hundreds of millions of state and local tax dollars annually in Oregon subsidizing growth of the built environment and related population growth. It would be pointless to enact policies that (directly) address this growth without first recognizing and rescinding these poorly understood subsidies.

The following breakdown, compiled by Fodor & Associates, are annual figures for Oregon and reflect FY 2000:

+ Infrastructures Subsidies ($738 million)

+ Economic Development Subsidies ($257 million)

+ Subsidized Planning and Development Services ($33 million)

+ Other Growth Subsidies (including traffic congestion costs and unmet infrastructure needs) ($115 million)

Based on an estimated state population increase of 63,800 in 2000, the growth subsidy calculated above amounts to about $18,000 per new resident of the state.

These figures omit important categories such as unmet (unfunded and unbuilt) infrastructure needs as well as many of the environmental and social costs of growth which impact public health and quality of life, including:

• $880 million in annual traffic congestion costs for the state’s three largest urban areas (created by pre-1999 growth).

• $672 million in needed school facilities.

A dozen years ago Alternatives to Growth Oregon commissioned a study of growth subsidies in Oregon from which the statistics above are taken. The executive summary and report are both linked here:

http://www.agoregon.org/page82.htm

Other related documents including the Governor’s 1999 Impacts of Growth study can be found here:

http://www.ocva.org/docs/index.html

Thanks! That’s some interesting stuff for me to chew on.

OK, now I’ll bite (speaking for myself rather than as a journalist, to the extent that’s possible): subsidies aside, defining “growth” to include both migration and birth seems to me like a fundamental moral error. To me, those are totally different things.

One values people (and the planet, etc.) above the possibility of people. This one makes sense to me.

The other one values some people (those who happen to live in an area attracting migrants) above other people (those who want to migrate). This one makes very little sense to me.

If you were proposing that Portland’s population be fixed by randomly deporting 10,000 additional Portlanders every year to make room for the 10,000 extra people who want to move in, I guess that’d at least make moral sense to me. But that doesn’t seem to be your proposal.

“subsidies aside,”

well, to be fair, my point was the subsidies.

“defining ‘growth’ to include both migration and birth seems to me like a fundamental moral error. To me, those are totally different things.”

Sustained, compounding, rapid growth (in anything) is not the natural order of things, is not something we can sustain, is disruptive, costly, and interferes with our ability to attend to the needs we already had before we got distracted incentivizing more people to come here, live here, build here. We obviously see this differently, come at this from different perspectives, but I’m not sure I’m not following your critique, Michael.

If we focus, as I think you are suggesting, on fecundity but ignore asymmetric movement of people we aren’t going to get a handle on this challenge. That would be akin to the tiresome global North-South argument over which is the bigger environmental problem: population growth or consumption growth. Besides, my point was not about deporting or anything of that sort, but about our billion dollars of subsidies that we’re spending to attract people here. Why we remain unaware of these subsidies, and consequently fail to grapple with this level of misallocation. You skipped right over that.

“to make room for the 10,000 extra people who want to move in”

Maybe this is one way we’re talking past each other. I would suggest that that figure of 10,000 people annually who want to move here is in no small part a result of the degree to which the aforementioned subsidies reward and encourage this movement. Let’s imagine we didn’t spend ~1B/yr subsidizing this movement/expansion/growth. How many of those 10,000 would still end up here? Since by a number of measures we are falling behind in our ability to provide services for ourselves (infrastructure, schools, social services, etc.), would a smaller number of additional Portlanders or Oregonians really be such a problem?

There is (or should be) no iron law of accommodation, whereby every municipality that enjoys high rankings of the sort that attract new residents must do everything it can to make room for any and everyone who might respond to the call of the new, now and forevermore. We seem to be operating on a version of that principle, but in so doing we precipitate a thousand little and not-so-little problems for ourselves down the road.

I’m not 9watts, but I’ll give you two excellent ideas on how to limit population growth.

1) The US is overpopulated to an unsustainable level. Stop all immigration – legal and illegal.

2) Raising children in a healthy home environment requires significant resources. Far too many men father children when they can’t even feed themselves. Solution: At birth, all males born in the USA shall be given a vasectomy. After attaining adulthood and showing responsibility in the form of being able to earn a living that could support a child, the state shall reverse the vasectomy for free.

Overpopulation problem solved. Society improved. USA goes from current “3rd world” status back to former “developed nation” status. Many other benefits too numerous to mention.

“stop incentivizing in-migration, reward growth.”

You want to sabotage our economy? How odd.

If we can’t come up with an economic system that does a better job of protecting what people value, the foundations on which our lives depend, then yes, I would be pleased to go on record as sabotaging *that* economy. I have no interest in an economics that ruins everything except for profit.

Oregon “enjoyed” out migration in the early 80’s. It was not fun.

Joe’s data is by census tract, so you can see where change is happening and not by clicking on each one. Go to CityObservatory.org for his response to Governing and for the research showing gentrification as the exception, not the rule.