Oregon’s 1997 freeze on taxable property values. The same law drives up the cost of new units

in inner North and Northeast Portland.

Of all the problems with Oregon’s spit-and-chicken-wire property tax system, one of the strangest might be this: It rewards developers who build new apartment buildings in Gresham while driving up the price of new units in inner Northeast.

This redevelopment penalty is an obscure but growing side effect of a system that also props up home prices in the central city and puts a disproportionate tax burden on East Portland and other recently redeveloped areas, the co-author of a new report says.

“In certain cases, it’s a disincentive to develop or invest,” Jeff Renfro of the Northwest Economic Research Center said in an interview Wednesday. “Potentially a pretty significant disincentive.”

For example: Miss Apartments, a 25-unit apartment building built in 2012 on North Mississippi Avenue and Failing Street, paid $49,910 in taxes last year — almost all of which, Renfro said, was probably passed on to tenants due to central Portland’s chronic shortage of rental housing. (Miss Apartments currently has a 0% vacancy rate, a property manager said Friday.)

“If you’re the developer, you have to make up that cost,” Renfro said. “One way to do that is to target higher-income renters.”

Meanwhile, the rented-out house immediately behind Miss Apartments, which was built in 1908 and is still protected by the 1997 tax freeze, pays a much lower property tax rate. For Miss Apartments, the additional cost works out to about $64 per month per unit, about 5 percent of the monthly rent at Miss.

It’s not a huge difference right now, which helps explain why apartment building keeps booming in inner North and Northeast Portland. But if central Portland land values continue to climb faster than those in the rest of Multnomah County, the penalty for redeveloping the central city will keep rising, too — quietly eating away at supply of new homes and storefronts in the highest-demand areas and allowing owners of the existing properties to keep raising rents higher and higher.

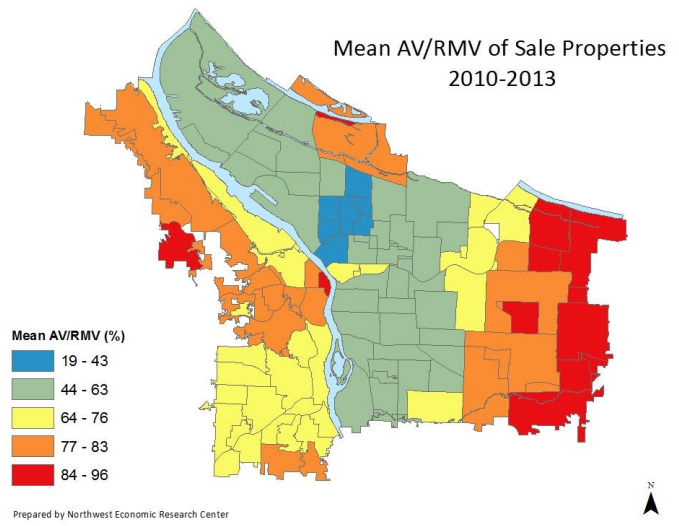

(Image: Northwest Economic Research Center)

Meanwhile, the same system would reward developers when they put up big projects in lower-demand areas. (The three-year-old 25-unit apartment building pictured above, on Southeast 148th Avenue, offers units at half the price of Miss Apartments with auto parking included. Its vacancy rate is 8 percent.)

It adds up to a system that makes it more expensive to create new homes and jobs in the walkable, bike-friendly, transit-rich central areas of Portland that are facing such intense demand.

It adds up to a system that makes it more expensive to create new homes and jobs in the walkable, bike-friendly, transit-rich central areas of Portland that are facing such intense demand.

The study Renfro co-authored, funded by the Oregon League of Cities and released Wednesday by NERC, shows that central Portland homes, especially in the formerly redlined neighborhoods of inner Northeast Portland, sell for inflated prices because the 1997 tax freeze left them with persistently lower tax burdens.

There’s an ongoing public conversation about changing Oregon’s complicated (some say “insane”; Commissioner Steve Novick says “outrageous”) property tax law. Gov. John Kitzhaber says tax reform is his top priority as he looks toward a fourth term in office.

But Wednesday’s NERC study also shows why property tax reform is poison to so many voters: even though it could equalize the tax burden and eliminate the current penalty on new development, it stands to reduce the property values of tens of thousands of single-family homeowners.

That’s exactly the problem with today’s system, Renfro said Wednesday.

“It’s not based on some sort of public policy goal,” he said. “It’s based on who bought when.”

— The Real Estate Beat is a weekly column sponsored by real estate broker Lyudmila Leissler of Portlandia Home/Windermere Real Estate. Let Mila help you find the best bike-friendly home.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

This is the price we pay for ballot initiatives being so easy to put to a vote. “Of course I want a tax cut, and I’m not going to ponder the long-term consequences!”

They are now driven by paid signature gatherers and big money….

The obvious solution seems to be another ballot measure, eliminating Measure 5.

Not sure I follow, could you clarify? New developments of residential property statewide are given an assessed value of 73% of their market value upon completion, whether such developments are located in inner NE or outer NE.

http://www.oregonlive.com/politics/index.ssf/2014/03/three_misconceptions_about_ore.html

Are you saying that because inner NE values are inflated due to windfalls associated with “locked in” properties, that new inner NE developments are similarly given inflated values and therefore disincentivized, despite the fact that all new developments will recieve a 73% assessed value? Not necessarily disagreeing, just trying to understand. Thanks

I think the easiest way to see the incentives is to look at the map:

Where the AV/RMV is lower than the 73% you cite (green and blue), then there’s no tax incentive to redevelop the land–in fact, there’a a disincentive, since you would be increasing the tax rate.

In contrast, if your current rate is already above 73% (i.e. orange or red), then there’s a tax incentive/subsidy to redeveloping since you lower your tax rate by doing so.

I understand those incentives, but I can’t imagine them having any significant effect. Generally speaking, if you change a couple single family residences into an apartment building, you increase the property value as well as the revenue to the landlord of that property. That increase, I would imagine, dwarfs the corresponding increase in property taxes due to the AV percentage increase.

More broadly I guess I’m not understanding the development goals implicit in the article. With redevelopment, we seem to be getting higher density regardless of where it’s happening, no? And higher density=good for transit/biking/walking? And isn’t having increased density in East Portland a good was to encourage walkable and bikeable neighborhoods in these underserved areas?

Believe it or not, East Portland *has* densified on-par with much of the inner neighborhoods, but now we’re realizing it’s not only about density. It’s a about streets (which are unfinished) sidewalks (which don’t exist) street networks (which are broken) and human-scale commercial development (which is illegal due to zoning).

The East Portland problem with active transportation is bigger than density, and it’s too early to tell if the City is taking the challenge seriously.

You’re right: the post implies that it’s better to have density in a place where there seems to be high and rising demand for housing (central Portland) rather than a place where there seems to be lower demand (east Portland). Just from a transportation perspective, increasing the supply of housing and job space in the central city is especially valuable because it makes the central city more affordable to people who want to take advantage of all the proximity and infrastructure that the central city already provides. That’s not to say that East Portland couldn’t use some more density, too.

As for the size of the effect, what matters to rental prices is the property tax penalty per unit. You’re right that it’s not huge (only about 5% in the example above). The point of this post is that the redevelopment penalty is now a meaningful cost driver in some neighborhoods and that it’s probably going to keep getting bigger until something changes.

Good questions. I didn’t attempt to get into the issue of Changed Property Ratios (the technical term for the AV/RMV value after redevelopment) but multifamily residential is actually assigned an AV/RMV value of its own, based on the countywide average AV/RMV for all multifamily residential. At the moment, it’s about 58%.

So when it comes to the multifamily development “penalty” discussed here, the relevant question is basically whether a property’s current AV/RMV is lower or higher than 58%. If it’s a lot lower — as it is in Boise/Albina/Eliot, the old redline neighborhoods — then unredeveloped homes receive a tax subsidy relative to redeveloped ones, which limits profitability from redevelopment and deters infill.

Most of the inner east side has current AV/RMV ratios pretty close to 58%, so the redevelopment of inner SE Division (for example) is unencumbered by the penalty.

Michael, could you share a little about your sense of how far this reform conversation might realistically go? Is there a chance it might tackle the creation of a split rate that moves some of the burden to a land tax over an improvements tax? (This is all new to me, so I’ll take all of the resources I can get!)

Great idea! Beyond my ken.

One would think the close-in increased rental costs would deter development….

All I hear about are the huge apt buildings being built with zero parking yadda yadda yadda. If there the redev taxes are lower, will we see more of these?

This is an important issue that affects Portlanders. Although redevelopment models could be considered linked to transportation, the focus on taxes as an incentive (or disincentive) to development seems like a stretch to include in a bicycle blog. Does “Real Estate Beat” need entries even if there is no bicycle related news?

Good question, Granpa – this one does stray a little further from bicycling but it’s connected because (as we’ve been writing for years) proximity is so important to biking.

The way I see it, there are two ways to improve access to good biking: you can expand bike infrastructure to new areas, or you can make it easier for people to live and/or work in areas that already have good bike infrastructure. Most of the time we cover the first way, but on the Real Estate Beat we cover the second way.

Thanks Michael. It strikes me that the property tax code is a pretty blunt tool if one is trying to encourage cycling. My recollection is that apartment construction was encouraged in east Portland to complement the MAX line and to encourage transit based car-free living. Also it is possible that the disincentive to redevelop inner NE Portland was put in place to protect cultural resources such as historic homes, or to protect the neighborhoods that haves historically been home to Portland’s disenfranchised black community. If you think that the Williams/Vancouver kerfuffle over the bike route was eye opening, try changing the tax code to encourage demolishing old homes to put up apartments and facilitate gentrification. Like I said, the tax code is a blunt tool, but it cuts two ways. One of the sharpest of this family of the blunt tools is the CARBON TAX! It is so sharp that politicians are scared to touch it.

The type of housing we build, and where we build them, is overwhelmingly important to designing a city in which all Portlanders feel empowered to ride a bicycle as a primary mode of travel. Any cogent, intelligent analysis of how (regressive) tax policy is affecting housing development is crucially important to our work of building a bike-friendly city.

1. The map isn’t nearly granular enough. I live downtown and I know that my place has risen in value quite a bit in 3 years, much more than the 3%/yr cap.

2. When a property is sold, the assessed value is reset, isn’t it? When the house behind Miss Apartments is sold, the tax rate will jump way up.

1) If you want, you can look it up on PortlandMaps.com. That’s where I got the data on Miss Apartments.

2) Yep, on redevelopment the assessed value is reset to the “Changed Property Ratio,” which is different for each county and land use category. It’s currently about 58 percent for multifamily housing in Multnomah County. The house behind the Miss has a taxable value ratio of 21 percent, which is about average for its neighborhood. If it were redeveloped this year, the taxable value ratio would more than double. Hence the “development penalty” described in this post.

Edit: as Doug notes below, I misread your question. No, the assessed value doesn’t reset at sale. It resets at redevelopment. California has a similar law, but it resets at sale.

Michael:

Not exactly what the questioner asked. A lot of the problem with Oregon’s tax initiatives, unlike those in California, is that the tax rate does NOT reset with a sale. So, the low tax rate on a house continues as it is resold. Only upon development, it seems, does the tax rate reset. Some have talked about changing this to “rest on sale”, as a way to address some of the inequities currently existing.

Thanks for clarifying. I previously lived in Florida where a sale resets the taxed value. It discourages people from moving around but it does keep property taxes more fair. The reset on sale thing is intended as a way of hitting people who move from out of state.

I swear half the time I try to explain this to people they tell me I am wrong and that it resets when you sell, even people who lived in Oregon when measure 5 passed seem to have this misconception. One thing that can really jump your taxes is adding an ADU to an existing home that is undertaxed, which is to some extent a disincentive to building adu’s where they make the most sense. Kol Peterson had a blog post awhile back about having to appeal his initial reassessment because his tax bill went from less than 1600 dollars to over 4000. He was able to get it lowered a bit but his bill still basically doubled even after the appeal.

I think there’s a lot of splitting hairs here. Your assessed value is an amorphous thing that can be challenged on an individual basis (my friend has proven this with the threat of a good attorney, whereas I’ve lost several challenges alone). The RMV is estimated every other year and has little bearing on the assessed value and total tax amount – as an example, my condo (bought late 2001 for $135K) had a 2009/10 RMV of $360,760 ($100K too high!!) and AV of $139,050 for a tax of $2237, and 2012/13 RMV of $221,480 (a little low) with AV of $151,930 for a tax of $2433. So my out-of-pocket went up ~$200 in the last 4+ years – which has absolutely no correlation to the fact I could rent out rooms for $150/mo more each due to rise in rental market demand (and that’s not in Portland where demand’s grown much higher).

As a developer I’d build based on demand/cost and this slight variation in out-of-pocket tax amount would be jitter in that equation. Of course I may also factor in livability which is an esoteric predictor of potential RMV growth. Some developers build for current demand; a good developer builds for (and builds in) future demand.

California (prop 13), like Massachusetts (prop 2 1/2) where I grew up, has a cap on property tax rate which was originally intended to prevent undue financial burden on aging homeowners (whose salaries tend to decrease with age toward fixed-income years). Unfortunately (or fortunately for some) it has the effect of ballooning the expense of homeownership during rising growth (thus accelerating rental demand).

was carless – you were pretty close: you do have an increase in tax amounts in CA but a cap on increase in rates, and it indeed takes a resale (unlike Oregon) to trigger a re-assessment. So yes, I moved to California specifically because I had bought a rental house in the early 90’s that I could no longer afford to pay for during the 2008 recession years, but now makes no financial sense to move out of as my current home. (My tax cost here is only 2x what it is in Oregon, despite now being worth 3.5x the OR place).

Very good story Michael. I learned a lot.

Interestingly, California is worse. You NEVER have an increase in property taxes, according to what I’ve read. There are homeowners in SF who pay less than $1,000 a year for property taxes and, since they outright own their homes, have an incentive to never sell – they would never be able to afford the neighborhood again.

I think the tax penalty exists, but I’m not sure how broadly it applies.

Consider someone who owns underutilized property. Maybe it’s a house, maybe an empty lot or store, whatever. It’s in an area that gentrified so market value increased much faster than assessed, creating a tax benefit. The owner wants to sell.

They could sell the property to someone who won’t cause a reset. The buyer would enjoy whatever use they can get with that restriction, and they get to maintain the tax benefit. That’s what they’re paying for, let’s call those two things X and Y. The property could also be sold to a developer who will make changes that reset the value. What they’re buying is the use of the land not bound by avoiding reset. Let’s call that X + Z where Z is the net value added by redevelopment. So long as Z is larger than the tax benefit Y there is no disincentive. The seller loses a little because they can’t transfer the tax benefit but they still gain by selling.

I think where there is an impact is on small rental properties where the owner wants to keep the property relatively small. A change such as adding a unit, or replacing a house divided into rental units with flats might not pay off because of the tax reset.

Good analysis. But isn’t a developer of a property on, say, Vancouver Avenue going to have to offer a tax-protected owner X+Y for a property, rather than X? Because some other buyer who doesn’t plan to redevelop is theoretically going to offer X+Y.

The tax benefits of properties with artificially low assessed values are “baked in” to their sales prices. A developer planning to do infill anticipates future taxes as part of his economic analysis and therefore what he’s willing to pay. The party that really gets screwed in this scenario is not grandma (who gets a windfall when she sells) or Greedy McDeveloper (who buys with eyes wide open), but the government, who can’t reap the full benefits of rising property values.

The tax costs will likely be more than offset by the revenue generated by the additional unit (in a healthy rental market). In a ROI calculation, the cost of building the unit is so much higher than the tax impact that the latter barely factors in. It’s the revenue projection that counts the most, and to a lesser degree the opportunity cost of the cost basis itself (i.e. low interest rates on a construction loan, or how could I better invest this money?).

Converting rental units into flats (condo-izing) makes the most sense in a growing real estate market (driven by low mortgage rates, steady job growth, and/or demographic shifts), which is different than a growing rental market (usually driven by rising mortgage rates and/or sudden job growth). In that case the tax burden also falls on the buyer, so it’s often simply neglected in the seller’s decision.

This is interesting reading, however there are many factors driving real estate investment decisions and property tax rates are not at the top of the list for developers/investors. The inner east side is largely a tremendous in-fill success and will continue because of market demand for vibrant neighborhoods evolving there.

i highly doubt that the signal exceeds the noise for this theoretical “subsidy”. if there is an effect on costs, its so minor that i would wager that there is not a single case of a developer working elsewhere or canceling a project.

fixing the property tax code is important… but not for this reason.

Yes, I agree that the impact is small for almost all projects. I think it’s more important to note that this distortion is probably only going to get larger unless/until the system is fixed.

There can be some serious downsides to infill. The Mississippi St neighborhood has sustained some this. Neighborhoods designed and planned to support walking and biking to jobs, services, school and entertainment. They also ought to be affordable…that is…truly affordable rather than ‘affordable’ based on some voodoo income formula, for people to actually live in.

In today’s Oregonian, is a story about some of the sobering consequences of infill and gentrification. Here’s a link to that story: http://www.oregonlive.com/portland/index.ssf/2014/03/affordable_housing_no_recourse.html