(Photos by M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Call it the people’s density.

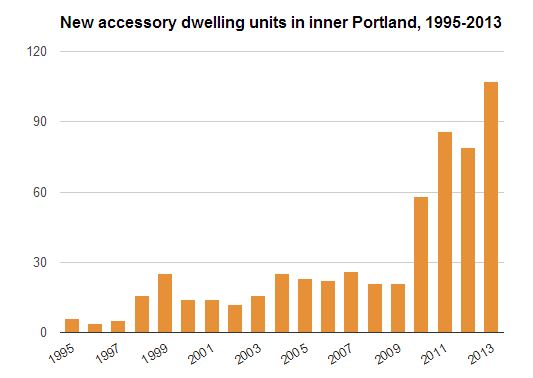

Four years after Portland slashed its transportation and parks fees for “in-law” units and other secondary dwellings in hopes of increasing the housing supply in its most in-demand neighborhoods, the city has gotten its wish.

Though they’re still far from common — it’s only about 3 percent of new dwellings citywide, and fans say those that exist remain in hot demand — the backyards, cellar doors and underused garages of Portland’s central neighborhoods are rapidly filling up with “accessory dwelling units,” which the city defines as living spaces of 800 square feet or less that have an entrance, bathroom and kitchen to call their own.

Fewer than half of them offer on-site auto parking. Then again, one in five households that live in them don’t own a single car. (Another 63 percent own one car.) And though banks still haven’t figured out a standard way to finance them — more on that in a future Real Estate Beat post — they’re popping up like mushrooms.

“In some of the inner neighborhoods, it’s as much as 10 to 15 percent of all new dwellings are ADUs,” said Eric Engstrom, the city’s lead planner on the issue.

According to a September 2013 survey that also gathered auto ownership, demographic information and many other details about ADU residents, the average rent of a Portland accessory dwelling unit was $811 plus utilities.

(Source: Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability.)

“There is this huge demand for the kind of housing that ADUs represent,” said Kol Peterson, who bought a traditional single-family house near Alberta Street in 2011 and built a new 800-square-foot home in its backyard for $110,000. Today, Peterson and his wife rent out the larger original house, live in the smaller one, and expect to fully recoup their investment in two to three years.

Some of the recent growth isn’t actually new construction. Many people are taking advantage of the fee holiday to bring longtime units up to code and make them legal. But Peterson said it makes sense that there’s “a crushing need, a huge demand” for ADUs in Portland and other growing U.S. cities, Peterson said.

Three-quarters of the households in Portland are “individuals, couples without children, or individuals living together,” Peterson said in an interview. “But the housing stock that we have is three-quarters single-family homes.”

Neither of those statistics has actually changed much since the turn of the century, which is when Portland eliminated its rule (still common in many cities) that the owner of an ADU must live on the same lot. And even the city’s fee cut slices at most $10,000 off the price of developing an ADU; more than half of ADUs cost $80,000 or more to build, according to the 2013 survey.

(Photo courtesy Moray)

What has changed, though, is Portlanders’ hunger for homes in walkable, bikeable, high-transit neighborhoods. Engstrom said that’s helped give rise to a cottage industry (so to speak) of builders and developers who have experience with ADUs.

“We were one of the first cities that I’m aware of to legalize them, but it’s been more recently that they’ve kind of taken off as an economically viable thing,” Engstrom said.

The specialist contractors include Orange Splot, Hammer and Hand and Green Hammer. They’re a rising share of the rental market, too: you can check out the current listings with this Craigslist search, recommended by Peterson.

two small homes and two ADUs developed by

Orange Splot LLC.

ADUs in the Portland area even have their own niche website, AccessoryDwellings.org, published by a few local ADU experts. As part of a temporary project funded by the Metro regional government, it’s now being updated almost every Friday with a new “case study” about a local ADU.

The case study project’s manager, Lina Menard, said she thinks Metro, the city and state all have an interest in increasing the supply of ADUs because it’s a way to increase housing supply without dramatically transforming neighborhoods or scrapping older homes. It also adds “flexibility over the course of people’s lifespan,” helping people age in place or with the help of their families without sacrificing privacy.

“This is a way to reconnect multigenerational families,” she said. “The idea of having nuclear families in single-flamily homes in the suburbs — we talk about that as the ‘traditional household.’ But it wasn’t.”

Engstrom said he also sees ADUs as a way to increase the population of a given neighborhood enough for more of the city’s commercial corridors to support everyday services like neighborhood grocers, hardware stores and coffee shops within walking distance.

“To the extent that we can have more people near them, it makes those streets more livable more likely to have basic amenities instead of just being trendy restaurant rows,” he said.

— The Real Estate Beat is a weekly column sponsored by real estate broker Lyudmila Leissler of Portlandia Home/Windermere Real Estate. Let Mila help you find the best bike-friendly home.

You can sign up to get an email of Real Estate Beat posts (and nothing else) here. Correction 2/26: An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the funding of AccessoryDwellings.org.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Having previously lived in Seattle, which is chock-full of ADUs, I’ve been surprised not to see them much at all here. It’s about time, and I’m glad the city is seeing the wisdom of allowing more of them. They can be a very important part of the density puzzle.

Having an ADU confuses the heck out of a lot of bankers and finance people. I lived in an ADU sized house and then built a new larger house on the front of the lot. I have been refused insurance and refinancing because my property doesn’t fit into a check box on their forms. “Wait, you have two houses on one lot???? Does not compute, error 405 file not found, mind blown” Getting a good property value assesment is also difficult. Once you get things figured out though, it is easy to manage property that is 15 feet away.

Anyone know where I can find a homeowner who would either rent one of these to me, or let me build one on their lot? All of the resources I’ve seen are for existing homeowners who want to build an extra house in their backyard. I imagine the legalities of this would be tricky, though.

It’s funny to hear spaces under 800sq ft called accessory dwellings. Most apartments I’ve ever lived in in this city have been half that size! Our current studio is just over 400 sq ft. Does that mean we are an accessory du too?

Garden sheds only.

Yeah, I hear you – 800 sqft is plenty for lots of households, it’s just very unusual in most new construction markets because so many of them are constrained by minimum lot sizes and bank loan formulas are written on the (often reasonable) assumption that more square footage always makes a lot more valuable.

One big thing that’s probably different about ADUs than your place now is that they have to be installed on the same tax lot as another, larger home. And you can only have one. They don’t have to be freestanding garden-shed style, though: basements, attics, etc., also count as long as they have their own kitchen, bathroom and entrance.

I was sorta being tongue-in-cheek. I know apt units in multi-unit buildings are not ADUs. But I just thought it was hilarious to read that spaces twice the size of our apt are considered ADU when on same tax lot!

By that definition, my house is an ADU. For the first few years of my ownership, I was aware of living in a perfectly good single-person house that had become sub-code just by being too small: no more such useful little houses would have been permitted. I’m so glad that has changed. I’d love to be able to build two more like it right on the lot.

My pal Brennan specializes in ADU construction…

http://micro-structures.com/

So my understanding of ADUs is mostly based on them being rental properties: converted garages, sheds, basements, attics, etc. that are rented out by the property owner. Seattle makes that pretty doable.

Offering them up for sale, on the other hand, is a whole different animal, and I’m sure entails big legal complications to have the lot subdivided, address numbers assigned, etc.

One way I have seen this done quite a bit up in Seattle is where duplexes were split into two tax lots. The terminology up there is “ZLL” (for “zero lot line” where the property is split right through the building). Other than that, I’ve never heard much about ADUs being sold off as separate properties.

I’ve wondered if they could be converted to freestanding condominiums so that the individual structures could be bought and sold, making it more affordable for people who want to be homeowners and for giving people an out if they decide they no longer want to be landlords.

GlowBoy is right — accessory dwelling units are (by definition) part of the same property as some bigger dwelling. The main house and the primary dwelling have, by definition, the same owner. If the property is split up legally so that the parts can be sold separately, that’s something (condos? subdivisions? who knows?) but it’s not what real estate people mean by accessory dwelling unit. And believe me real estate people, lenders, etc, are already confused enough. 🙂

The relevant point is that the size of your dwelling (whether it’s apartment, house, ADU, whatever) is probably the single biggest factor in its long-term environmental impact. A small code house can be gentler on the environment than solar palace. Accessory dwellings, tiny house, apartment, whatever — any way you can live smaller and still be happy is good.

Could they create a co-op, which is extremely common in NYC apartment buildings? The property wouldn’t have to be split into two lots in that case. The way co-ops work is that you own shares of the entire building, and the number of shares you own (in relation to the other owners) varies according to the characteristics of the unit you occupy. If a building has 10 apartments that are exactly the same size, then perhaps every owner in the building would have 10 shares each of 100 total. If five apartments were twice the size of the other five, then the owners in those apartments would likely own 15 shares (75 shares in total) each and the others would have 5 shares each (25 shares in total). If you have more shares, you will pay higher maintenance fees, the asking price for your unit will be more expensive, but you’ll also get a larger tax deduction for your share of the mortgage on the building. Essentially, you become part owner of the whole building, rather than owning your own specific unit like with a condo. The only time people have trouble getting loans for buying into a co-op is if the co-op itself has been very badly managed and is in danger of defaulting, but that’s pretty rare. (And in any case, you’d have to be pretty foolish to buy into a building that has been that badly managed.)

Substitute “lot” for “building” and I don’t see why that couldn’t work in situations where a single tax lot contained both a main house and ADU. A person buying an ADU would actually be buying shares of the entire property. Obviously, they would have fewer shares that the occupiers of the larger house, but they would become owners instead of renters.

Maybe it’s too communist-sounding for libertarian Portland — I mean, jeesh, co-operatives!

A small correction: To clarify the story’s comment about AccessoryDwellings.org : the web site is not a project of any government agency. It is a grassroots effort started and edited by me, Kol Peterson, and local developer Eli Spevak. The series of case studies by Lina Menard we have every Friday have been funded through Metro and the Oregon DEQ. Thanks!

The once-small town that I grew up in, in SW FL, had these all over the place. We called them “guest houses”. It was a very vacationy area and it was a good way to give your visitors from “up north” a place to stay that had some privacy. Lots of them got rented out or used for mother-in-law suites, too. I don’t recall any that got sold as independent properties, though. Most were one-bedroom cottages or studios and all had baths & small kitchens. Some also served as pool houses in the nicer parts of town. It was a great way to give yourself less yard to mow and it still makes sense.

I just find it funny since my house (1920-30ish) kit house is only 850ish sq. feet not considering the basement. Every other house down the the block is nearly identical to this one. The only real differences are little add on’s (a built up entry way on this one, perhaps an attic addition on that one) but the layout is the same in each one.

You really want to talk of complications, my neighbor and I have easements on each others property for a shared driveway and garage. We’ve talked of doing a ADU on the shared garage, since either side can hardly handle even the smallest of cars. But the complex legalities of it (since it’d be one or two units on two separate properties) even during a casual conversations became apparent.

I do gotta admit that having grown up in the burbs most my childhood, the smaller sized house appealed to me. I hate to clean, and less space is more time for other, more important stuff like trolling local bike blogs…..

Michael, not sure what you are trying to show here. ADUs are great, but “people’s density”? Really? 50% of ADU owners have incomes over $100,000. Most ADUs are relatively large footprint (800 sq ft). Most were financed out of owner savings, meaning the people that built them had $80,000 sitting around.

These are great, but let’s be honest about what they are: a way for wealthy homeowners to build a rental property.

Let’s see where these are being placed and who is living in them before we think they are some sort of solution to density and not just a way for upper middle class folks to rent out part of their property.

Its still not giant developers and property managers.

If an ADU is being rented for $800/mo, it is providing an affordable housing alternative for the occupant, regardless of who owns it.

You raise great points, Paul. I noticed those income stats, too. As I say above, we’ll be covering the troubling financing barriers in a future post. There are signs that it could be shifting to make ADU construction more accessible for the middle class.

Also, as John and Psyfalcon say, most of the benefits of these projects go to (a) not-necessarily-rich tenants and (b) upper-middle-class homeowners rather than upper-class developers.

In any case, what I’m trying to show here is that ADUs have very quickly become much more common, and to explain why.

Paul G, you are totally right to point out income issues, which totally deserve examination — but your numbers are bit off. According to the DEQ report (which I assume you are drawing from) the percentage of ADU owners with household incomes of $100,000 or more is 36%. That comes from taking the numbers in table 68 of that report and adjusting for the number of people who refused to answer the question. Hope that helps! Martin

I am building a tiny home on wheels, which I hope to have completed by the end of April. If you are in the Belmont/Cesar Chavez neighborhood, come check it out. It is located across the street from the Walgreens. It will be for sale too!

I’m having an interesting discussion on twitter about ADUs right now. A friend called it “humane densification” but I counter with “who is it humane FOR?” My super bikey vegetarian car-lite family (3 kids + 2 grownups + 1 dog) is highly motivated to move into the central eastside AND we’re in the top income quintile. We are poster kids for go-go green density rah rah. But the runup in housing prices is pushing us out.

Different densification schemes favor different demographics. Condos favor DINCs (Double Income No Kids) or single professionals. Rowhouses and townhouses favor young families. ADUs favor established homeowners and relative transient renters (because the ADU can’t be sold) — more singles. Obvs. there are exceptions; I know a family of four living in a 1BR apt with no car and they love it. But across a broad demo, most families won’t go for that, so they’re looking outside the city core.

ADUs are popular because they don’t much alter the character of a neighborhood, which is great if you’re established in the neighborhood already. But the side effect is that housing stock for families (2+ BR) become prohibitively expensive, and those people are forced out of the core.

“ADUs are popular because they don’t much alter the character of a neighborhood, which is great if you’re established in the neighborhood already. But the side effect is that housing stock for families (2+ BR) become prohibitively expensive, and those people are forced out of the core.”

Not sure I’m following your logic. How does the establishment of ADUs contribute to the runup in prices of homes for families? I don’t see how ADUs would be a major factor in how much prices have gone up.

But the family that buys the house with a rentable ADU then gets the rental income from it which helps pay the mortgage. And the family that buys a house with no rentable ADU has the option of building an ADU to get that rental income. The vast majority of Portland houses still have no ADU.

Suppose an ADU produces a monthly rental income of $800 ($9,600/yr) forever,i.e. an annuity. Using 6% discount rate, the net present value (NPV) of that stream is $160.000. Which means that if you can build that ADU for $80,000 – and it should cost less if you do some of the work yourself – then it is financially a good opportunity. Put it another way, if you spend $80,000 to build an ADU and get $9,600/yr in rent, that is a 12% annual return which is very attractive.

That is if you do not plan on selling the house soon. I suspect – no evidence – that currently ADUs are not fully valued, meaning an ADU with a NPV of $160,000 is adding far less than that to the home’s market value. In that situation, the buyer of the house with a rentable ADU is getting the better side of the deal.

My house has a basement that could potentially house an ADU. Alternatively, the one-car garage could be rebuilt as a two-story with an ADU on top. Both are intriguing options. I could certainly use $800/month.

Caveat – my thoughts above did not consider the tax treatment of ADU-related income and expenses.

There are many restrictions on the look and location of an adu. It is great that the city is continuing to waive the excessive fees, but it would be nice if they would back off some of the codes a bit as well. Kol’s class is excellent, I took it when we were considering adding an adu to our property.

@Glowboy, @John Liu — Look, I’m basically pro-ADU. I don’t think ADUs are responsible for the runup of prices in inner SE/NE. And I know there are specific cases that can make ADUs make economic sense — our own family is in this position so I’m doing the math in a really personal way. (Although that math also means becoming a landlord, not a great prospect for everyone.)

What I’m talking about is the general fabric of the neighborhood, and the overall trends that encourage/discourage certain demographics.

Imagine you’re a family of 4 making $65K (top 40% in Portland) and at a stretch you can afford about $300K or $1500/mo for housing. Which neighborhood are you more likely to move to:

a) one with mostly 2BR townhouses for $300K

b) one with mostly 1BR condos for $300K

c) one with lots of 3BR houses for $400K, and some 800SF studio ADUs for rent at $1000/mo.?

(I’m leaving unspoken d) a surburb with lots of 4BR houses for $300K, but a 40min commute on a freeway.)

Can you see now how ADUs would encourage certain demographic patterns? Michael even points this out in the article: “Three-quarters of the households in Portland are individuals, couples without children, or individuals living together.” Those demographics are better served by ADUs.

Excellent idea. In the early days of our marriage we rented a self-contained guest wing in a larger estate home.

I understand your point, but I think the character of Portland’s close-in neighborhoods is already fairly set. Developers are not tearing down blocks of single-family houses (your type “c)” neighborhood) to convert the neighborhood to multi-family (your type “a)” and “b)” neighborhoods). Nor are they doing the reverse. There are some multi-family buildings going up in neighborhoods that are otherwise mostly houses, but they are usually going on the commercial streets, not in the residential interiors. That is what I see, anyway, I don’t pretend to know about every neighborhood.

So I don’t see that there is an overall trend to more type c) neighborhoods and fewer type a) and b) neighborhoods. I think there is a slight trend of type b) and c) buildings creeping into type a) neighborhoods, but basically the mix of neighborhoods looks largely static to me.

I do get that ADUs draw singles and couples to type c) neighborhoods. Demographically that would mean a slightly lower percent of type c) residents are families and a slighty higher percent are singles/couples. But that isn’t actually blocking a $65K 4-person family from moving to a type c) neighborhood, because they can’t live in the ADUs anyway.

Unless, as we discussed, ADUs are causing house prices to rise so much that these families are priced out of type c) neighborhoods. The house with an ADU certainly doesn’t increase the value of the surrounding ADU-less houses, so the only houses whose value is increasing is the few that have ADUs. But it would be the same for any home improvement that those homeowners did; a kitchen remodel would also increase the house value, to the chagrin of the hopeful buyer.

Maybe off topic – the price of housing is rising fast in Portland because there is significant demand (desirable city and people who put off buying for 5+ years during the housing crash), mortgage rates remain low by historical standards, and inventory of houses for sale is pretty tight (housing development stopped dead for the crash years, some homeowners are still underwater and can’t sell). It will keep rising until that combination of factors eases, and then it will rise at more of a long-term inflation rate, until the next bubble/bust cycle. That’s my view anyway.

I think we agree violently.

My point is that when the densification tools favor existing homeowners, the net result is to price out most families as Beth comments below. The ADUs themselves aren’t forcing out families, but they lock in existing stock and prevent other schemes (rowhouses, etc.) that might smooth out the price curve. There aren’t enough commercial corridors for the apartments the city would need.

My fear is that we will see the increasing density and think the affordability problem is solved. ADUs will let us house students alongside semi-millionaires. But if you fall in the middle: good luck in the suburbs! There’s less and less room in the city center for families like mine, especially if they’re not as rich as mine.

So my goal here is not so much to shout down ADUs — I like them! — but let’s not kid ourselves that they’re going to relieve the housing pressures you describe.

I shudder to think that $800 a month for a small, one-bedroom apartment is now consided to be an “affordable” and “reasonable” rental rate. Anyone working at $10 an hour or lower cannot afford to qualify for such an apartment. When the prevailing guideline for landlords to approve new tenants is that housing costs should not exceed a third of one’s income, I fear that Portland is becoming a city of mostly upper-middle income adults. That’s not a sign of a healthy, diversified housing market, or a healthy economy.

Woe to the city that depends upon its upper-middle income earners to make the local economy thrive. That segment of the poppulation is shrinking fast.

If you think $800 is bad for a small 1BR, try housing a family that includes (I hope) non-wage-earning kids. Additional bedrooms don’t cost much less than the first one. 3BR houses have suddenly pushed up near (and usually above) the $2000/mo mark in most of semi-inner Portland.

Do a quick search though. You can find cheaper apartments but not by much. Anything less than 700 is either in far SW or out past 205. Its been that way for years too.

@beth ADU’s are more expensive to build per square foot than other homes, so if you build one to use as a rental it isn’t going to be on the low end of the market. However if you build it like Kol did they are quite energy efficient so residents can get some of their rent back from lower utilities.

What I wonder is, given land, construction and financing costs, what is the lowest rental price (maybe on a per sq ft basis) economically viable for a housing development in close-in Portland? By “economically viable” I mean the rent has to provide enough profit to the developer that it makes sense to borrow the money and build the project? Does anyone have good cost information?

Maybe the reality is that, just to pick a number, $500/mo, in new construction only buys a very small square footage.

My understanding is that in the “old days”, I mean in the early 1900s, a single person earning the lower end of the wage scale at the time – the equivalent of $10/hr today – would commonly live in a rooming house. Basically like a dormitory for working adults. They wouldn’t typically have an apartment of their own. That wasn’t just young people recently out of school. It was older adults as well. People who were earning somewhat more might have lived in one-room apartments, with hide-away beds (“Murphy beds”), essentially studios.

I believe that after WW2, living standards changed and the typical person started occupying more space, at every income level. Buildings could be constructed quickly, incomes were more equally distributed, there must have been many reasons for this shift.

Perhaps the pendulum is swinging back. Maybe in the Portland of 2030 and 2050, it will be common to live in rooming houses, which we’ll call “micro-apartments”. A studio apartment may be quite a few steps up the income scale. Middle-class families may be pleased to have a two-bedroom apartment. And you may have to be some considerable distance up the income scale, bordering on affluence, to own a house, any house, even a small house.

It might not be just economic forces driving this. On this blog we talk about plenty of other forces that point in the same direction. The desire for more urban living, smaller environmental footprint, traveling shorter distances, using more bike and foot and transit. All these point to denser living in smaller spaces.

Does that sound plausible? Or maybe my knowledge of history and sense of current trends and economic/social forces is all wrong?

I ink your analysis makes a lot of sense, but I don’t the majority of Americans — and that ain’t the “typical” city center Portlander anymore, sorry — won’t go along willingly or quietly. I think any movement towards what you describe (and which I agree with a lot of, BTW) will be ugly and fraught with complications as those with means try to pay their way out of the kinds of scaling down you describe.

Good article. Thanks!

The “tiny home movement” is a sham. Time and time again, it’s wealthy people trotting out eco / minimalist / zen ideals to justify their lives of fairly-well-off luxury. They live small because they can afford to– and spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to build on a split lot that used to be somoene’s backyard or side lot. This is definitely changing the character of Portland’s inner neighborhoods, particularly in SE right now, and it’s almost universally for the worse. Developers can get away with flipping the main house AND selling or building upon even a modest yard. Both homes go to deep-pocketed transplants from out of state whose only goal is to live near trendy bars and restaurants– who cares about the neighbors that now have 1′ of clearance between their house and the uptight new folks next door? The new folks’ expectations are spelled out completely by the large mortgage and luxury SUVs parked out front– so much for “simple living when they start calling in noise complaints on long term residents who don’t fit their imagined ideal of affirmational Portland living.

And let’s not forget that the majority of tiny home dwellers do not have children. A mostly-adult community, if that’s really the trend we’re seeing evolve in inner eastside neighborhoods, not only changes the feel of a neighborhood, it also changes the politics and tax revenue of that community, as many young, childless single adults are not inclined to support public education or afterschool opportunities for kids — nor are they as inclined to support measures that assist the rapidly aging part of the city’s population. If this movement really picks up steam it could mean the rise of socio-economic monoculture.

Data, please.

Beth’s correct about the family type of most ADU dwellers. You can see it in the report linked above: http://www.deq.state.or.us/lq/sw/docs/ADUReportFRev.pdf

But Beth, what I think you (and some other folks in this thread) might be overlooking is the idea that increasing the supply of one type of housing takes pressure off a bunch of adjacent types of housing. Even if ADUs are mostly inhabited by “relatively transient renter” singles, as Paul correctly points out, that means that those people aren’t competing quite so much for space in three-bedroom houses, which makes the three-bedrooms slightly more affordable to families. And so forth.

I’m not saying that the type of units we build doesn’t matter at all, and a lot of good points have been raised here about the ways it does. But people (particularly Portlanders, maybe) are so good at adapting to whatever weird-ass housing circumstances are available that I think the most important factors in the price of all variety of market-rate units are fundamentals like overall housing supply and demand. Supply and demand for each the various niches is relevant but secondary.

Given the current oversupply of single-family housing stock that Kol brought up in the article, if anything our housing stock is currently engineering the city to be full of nuclear families … and failing.

I design in the Park Model RV Format. 1.5 bath, L.E.D.lighting, On Demand H/W, D/W, W/D and the ability for Solar power. These homes could fit most ADU standards if built with SIP’s. Finding a Factory to build them is the issue. Factories are geared to build Modular Homes and Park Models are just a sideline. I am sharing Ideas on facebook after visiting nine factories with no interest in new Ideas for expanding their markets.

what I am missing about the cost?

From what I surmise, the demand for ADUs must significantly exceed the capacity of contractors to build/install. In the prices 2017 I have been quoted ($250/sq foot+ for a PREFAB unit), there is of course no land component as I already own my residence and the land. Therefore, the cost should not vary much from one market to another ESPECIALLY on a prefab as the cost to build it is the same whether that prefab gets installed in Alabama or California (only labor cost of install should vary). However, In Alabama I can buy a new home, stick built including land for under $150/sq foot. So how can a prefab unit, no land, be $250+? The only conclusion I can reach — the manufacturers/builders of these units are putting too much profit into these and some foolish homeowners who don’t know any better will buy. I am in California so why I am getting these ripoff prices as our state just reduced the cost, time and requirements to install ADUs.