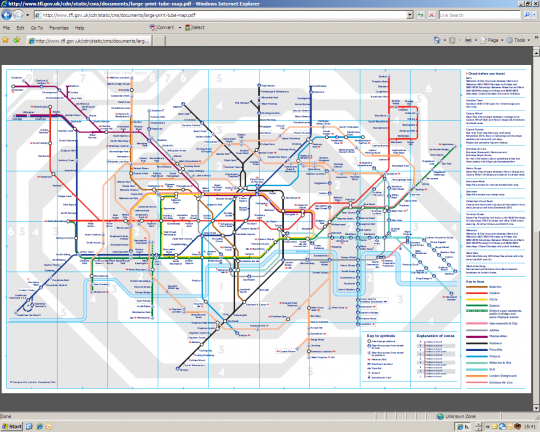

(Image: Transport for London)

London is making it happen.

“It dwarfs any equivalent program, certainly in the UK, probably anywhere in Western Europe.”

— Ben Plowden on London’s new $1.4 billion biking program

The last time he visited Portland, in 2003, Ben Plowden was several years into a job as the first full-time director of Living Streets, a small walking advocacy group. The city he worked in, London, had recently created a new regional government.

When Plowden returned to Portland last week, it was as the London regional government’s top surface transportation official – and he was here to explain how and why the region has just approved a $1.4 billion investment in biking over the next decade.

If spent as planned, Plowden said it’ll be one of the biggest municipal investments in cycling in the history of the world.

“It dwarfs any equivalent program, certainly in the UK, probably anywhere in Western Europe,” Plowden said of the $130 million annual budget, which will be divided among 1/3 education and enforcement programs and 2/3 infrastructure.

So something is working in London. But what? Last week we visited two events by Plowden, whose trip to Portland was sponsored by the public transport nonprofit Transit Center, to find out. Here’s what we learned London has.

1) An anti-congestion charge.

(Photo: Mark Ames)

Since 2003, driving a car into central London between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m. has cost $18 per day. The proceeds go into the regional transportation budget.

How was this approved? The key, Plowden explained, was support from freight customers.

“The reason that the congestion charge went in in 2002-2003 was that business knew how much congestion was causing them,” Plowden said. “It took a whole lot of discretionary car use off the network overnight.”

Here in Portland, there’s deep awareness among businesses of the job-killing costs of auto congestion. The problem, as we reported last month, is that the Port of Portland and some other freight customers believe that increasing auto capacity is the only viable way to reduce congestion; in a region where toll roads are almost unheard-of, they see an anti-congestion charge like London’s as impossible.

I asked Plowden whether toll roads were common in London before its anti-congestion charge began. They weren’t, he said.

2) A politician who rides.

The most important person behind London’s biking improvement is the one at the top: London’s center-right Mayor Boris Johnson.

“It’s difficult to exaggerate how important Boris being a commuter cyclist is,” said Plowden. “He carries his stuff in a rucksack on his back. and he’s done it basically his entire working life. … Like the mayors of Copenhagen in the 1970s, that’s a really important part of of making cycling what it is.”

After two terms, Johnson is returning to Parliament next year with his eye on becoming prime minister. Plowden said his departure will be “a sad day indeed” but called it “unlikely” that the next mayor will do anything worse for biking investments than to slow them down somewhat.

“This is actually quite an important part of the political landscape of London now,” he said.

(What about Portland? Well, as we shared last spring, no member of our current City Council spends much time on a bicycle.)

3) A very strong regional mayor system.

(M.Andersen/BikePortland)

Johnson’s commute habits wouldn’t matter much if he, like his predecessor Ken Livingstone, weren’t in control of almost every lever of power in the region.

“Ken Livingstone said if I’m elected, we’re going to have a congestion charge, and within two years we had one,” Plowden said. “Boris Johnson said if I’m elected, we’re going to become the world’s greatest cycling city. And we’re now spending a billion pounds on that objective.”

Advertisement

The “lesson of the London story,” Transit Center Executive Director David Bragdon said Friday, is “unity.”

“These are the results of really good governance structures and clear accountability for who’s doing what,” said Bragdon, a former president of Portland’s Metro regional government. “Americans, we’re very much in these jurisdictional boxes. These structures, they constrict us.”

Bragdon argued that the problems of concentrating power among a few people are outweighed by the advantages of the public knowing who to blame for its problems.

4) An organization built to see the big picture.

One effect of London’s integrated governments is that it put the same agency in charge of both arterial roadways and public transit.

In Portland, the Oregon Department of Transportation wouldn’t save much money if people driving on Powell switched to buses, or if people riding buses switched to bikes. But because Transport for London runs the whole transportation system, it saves money when the whole system gets more efficient.

Transit and bikes are efficient. Transport for London noticed – and started investing heavily in making them better.

In terms of vehicle road space, Plowden said, “buses are way way way more efffieient than anything else. Cycling is second. … If we have a finite amount of space and amount of money and people are going to be moving around the city, what’s the most efficient way of doing that? You have to start making the hard economic arguments.”

But if Transport for London hadn’t been able to see the whole picture, those arguments might have fallen on deaf ears.

5) Urgency.

(Photo: Nicolas Chinardet)

For all that, Plowden said, London might have accomplished little if not for two coincidences that created a sense that the city had no time to spare.

Starting in 2004, the year it won a bid to host the 2012 Olympics, London was on a deadline. If it didn’t have a massively functional system for car-free transport by that summer, it would be swamped by traffic.

“We set an objective that nobody except an elite athlete would arrive at any Olympic event with a car,” Plowden said.

In the run-up to 2012, London launched a bike share system, improved three rail lines, started running a new high-speed rail and built a cable car across the Thames.

Then, in late 2013, a series of six biking fatalities over two weeks seized the public’s attention around the need for biking improvements. Plowden called this a key catalyst for London’s massive investment to come.

6) Great ideas from other cities.

(Photo: Bike Texas)

Plowden didn’t mention this at all last week. But one of the most important things about London’s accomplishments is that every single one of them had already worked elsewhere.

Amsterdam, just across the English Channel, has billions of dollars worth of the world’s best bike infrastructure. Modern bike sharing came from Paris; the anti-congestion charge, from Singapore. Seville, Spain, had seen biking soar from 0.5 percent in 2007 to 7 percent biking in 2012 by rapidly building a connected 80-mile network of protected bike lanes; biking advocates across Europe are now looking to it a model.

One of the best things happening in the world right now is that it keeps getting easier for ideas to spread from one country to another. London’s huge victory in the last few years stems from Londoners like Plowden who decided to start stealing neat ideas from Paris, Amsterdam and (yes) Portland, Oregon.

How do good ideas spread? One way is when smart people carry them across the ocean to talk about them.

See you again in 2027, Ben. Meanwhile, we’ve got some work to do.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

7 percent biking in 2012

6% in 2014 and commute to work mode share is much lower:

http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/jan/28/seville-cycling-capital-southern-europe-bike-lanes

also, I think Michael miss used miles instead of kilometers per your linked article

Good catch, but I think our language is actually correct: as I understand it Seville has 80 miles total, 50 miles of which were built almost at once in 2007.

Your language says ” by rapidly building a connected 80-mile network of protected bike lanes”, but as the linked article states, “a full 80km (50 miles) of which would be completed in one go.” The remaining miles were not completed rapidly. That is what i was questioning above.

Different mayor please.

We have a mayor?

Maybe we should elect a conservative, like Boris.

(kidding, I know the GOP pulls your card if you mention bikes in any sentence that doesn’t also include words like scofflaw, freeloader, or waste/pork)

It would be fantastic to get some of these changes going here in PDX. However, we will need to find a differt catalyst than what was used in London.

How do we get people who drive supportive enough of people who bike to get approval for biking infrastructure? We would need people who drive to understand that for ever person who rides a bike or takes transit, its one less car on the road to slow their commute. We would also need to further encourage people who drive to become people who bike or take transit. Perhaps if we had a congestion fee, trimet could lower fare prices to make transit more affordable while still having enough to pay for additional infrastructure and bus lines. Some areas of the city still have very long bus commutes.

I don’t think it’s about popular support as much as it’s about needing *leaders* in city and regional government to take charge and make the right decisions as a whole. True leaders will take a leap and make tough decisions that might initially face some backlash. If governments only catered to popular (or perceived as popular) opinions and the status quo we’d still be in the dark ages.

From my understanding, most neighborhood associations hold a lot of power in this city, and none of them bicycle. Freight and commercial interests also hold a massive amount of influence, but according to them “cyclists aren’t valid means of transport.”

Great points on who holds influence in Portland! It’s really too bad that old-school freight interests have such a stranglehold on Portland, because we’ve now seen dozens of studies, as well as many real-world examples around the world, in which bicycles can more easily cheaply (and with dramatically less resulting congestion) carry a huge percentage of freight within a city. In fact, just last week I saw an article touting cargo bikes as the next big urban trend.

Cars, trucks, trains and planes are great for transportation *between* metro areas, but once you’re within city limits, that space needs to be for PEOPLE, like it is for increasing amounts of enlightened cities. Transportation is about *space*, and single-occupancy cars are not only the least efficient means of moving people within dense areas that has ever been invented, but all the big-oil interests and heavily subsidized concrete walled-off rivers (that destroy neighborhood connectivity) have only made getting around in cities worse all the time. Plus, our car-focused infrastructure fully encourages (and even depends on) so much additional sprawl every single day in the U.S. that this Ponzi scheme (which is what it is: never paying in the long run for short-sighted, extremely low-density developments) is guaranteed to collapse eventually.

Therefore, what London and other cities with bold leaders are doing is the only logical way–with ALL road users in mind–to intelligently deal with congestion, as well as maximizing the value of places.

I hope their 1/3 to education and enforcement is aimed primarily at drivers. We could double mode share next month by enforcing the law and adding some signage and paint in the right places. Then, require everyone pass a road test on a bike (or trike) before getting a driver’s license and suddenly everyone might realize that it’s very rude to operate 2 tons of metal at +30mph within arm’s reach of a vulnerable user.

Having lived in London recently, I’d say that, if anything Boris is behind the curve on keeping up with the active transportation demands of his citizens.

For almost everyone in the greater London area, driving a car just isn’t feasible (congestion charge or no) due to the geography of the city and the fact that there are no urban highways or even really major boulevards.

Moreover, mass transit in London is running at overcapacity during peak periods and is struggling to cope with demand; on many tube lines they literally cannot run trains any more frequently than they already are (1-2 min intervals) and every car is full. People are desperate for more alternatives.

Compare that with Portland, where driving is the norm. Moreover, a large number of people that vote see bicycles as a symbol in a larger cultural war against their 1980s way of living. Politicians are worried about getting too far out in front of voters here with even minimal streetscape changes in favor of bicycles.

As progressive as Portland is, fighting against free parking and driving rights cuts across ideology and is a sure way to lose votes from the older crowd that likes their neighborhood exactly as it is and also happens to vote early and often.

I often think of Portland as progressive in attitude and symbolism but actually fairly conservative in practice, when it comes to changes in the metaphorical your neighborhood or your way of life.

Incredibly good points, Andrew M! It’s all the more reason for us to campaign as hard as ever to change our horrific car-centric policies that favor ZERO people, including those who solely get from A to B by car!

It’s true, as others have mentioned, that London is almost unfathomably larger than Portland, but cities around the world that are our size are doing the very same things that London is doing (if not more when considered on a per capita basis).

Speaking of which, I’m really glad that Seville (population: 700,000 in the city & 1.5 million in the metro area) was also included as an example. I was there in October, and the protected cycling network (most of which was built in ONE year!) was everything I had hoped for and more! You just can’t believe how heavenly it is to bike on Dutch-style infrastructure. The closest approximation I’ve experienced in the U.S. is the Indianapolis Cultural Trail. If it can be done in Indiana, surely we can make this (and much more) happen in PDX! Completing 500 feet or whatever of Marine Drive trail in 10 years is not cause for any kind of celebration. We’ve GOT to move faster.

London and Seville are just two of literally hundreds of great cities around the world that are taking people-friendly infrastructure to levels that will soon reasonably approach what is seen in Holland and Copenhagen. Even Pittsburgh’s mayor is 100% committed to changes that are every bit as bold as this.

It’s increasingly important to keep pushing our “leaders” to, well, *follow* us–not to mention catch up to what you can plainly see is happening in great cities all over the world. Again, these changes will benefit ALL road users. The investment will pay back many-fold, as studies continue to clearly demonstrate. I wish we weren’t so deathly afraid to spend a dollar in Portland for such an obvious near-term payback.

Plus, London’s mayor has been biking to work for his entire work life. Would it really be so difficult for ANY member of City Council to bike to work regularly? Like the article states, it would make an enormous impact. We need leadership so very badly on the non-car-clogged (i.e., non-1950s-thinking) approach to transportation and infrastructure…

Comparing Portland to a city that’s over 10x in population and several times more dense. Totally realisitc. /s

When the return on investment is so high, not investing in bikes is irrational. So here’s to the Green Hierarchy and getting the budget fixed. Upgrading our bike infrastructure to London levels, especially around schools in the outer neighborhoods, is beyond affordable it’s the best option.

Although I disagree with Andrew about why Portland is slow. I think that biking, and maybe even more so family biking than commute biking, is mainstream in Portland. Parents choose to live here so they can have safe routes to school and so their kids can be active in the neighborhood.

In my estimate Portland is conservative because PBOT and city gov’t are scared of their own shadow. There is no coherent opposition to biking in Portland. If you conduct outreach in a certain way you can guarantee a parking-first result, but that doesn’t have to be the case. Maybe there used to be an anti-bike lobby but they are gone and all I see are NIMBYs and a city gov’t scared by their imagination.

Is the bicycling-mayor a common theme in cities that are pushing ahead infrastructure for cycling?

Yes. If not a mayor, then someone else who is a highly-visible community leader. Numerous mayor examples:

Indianapolis, Greg Ballard

http://www.bicycling.com/news/advocacy/conversation-greg-ballard

Chicago, Raum Emmanuel

http://www.triplepundit.com/2013/10/bike-loving-mayors/

Denver, John Hickenlooper

http://www.denverpost.com/election2010/ci_15673894

Boston, Thomas Menino

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/09/us/09bike.html?_r=0

Houston, Annise Parker

http://www.bicycling.com/ride-maps/featured-rides/houston-we-have-less-problem

Duluth, Don Ness

http://www.bicycling.com/news/featured-stories/town-cycling-saved

Pittsburgh, Bill Peduto

http://pittsburgh.cbslocal.com/2014/11/13/mayor-peduto-defends-citys-new-bike-lanes-answers-the-bikelash-from-drivers/

Great list, LM! For anyone who hasn’t seen this video of Pittsburgh’s Mayor Peduto, be prepared to be even *more* embarrassed by our lack of ambition: http://www.treehugger.com/bikes/pittsburghs-mayor-wants-copenhagenize-his-city-video.html.

Granted, our elected leaders continue to say that they WANT and NEED to hear from us! We have to keep encouraging them (in the most professional, respectful and positive way possible) to make Portland more people-friendly. They will only feel more comfortable to take chances on reversing decades of car-first policies if they are confident that they have lots of support from the community.

I think the “Portland process” scares them (very understandably). Plus, to make things more challenging, we have a “weak” mayoral system here, as everyone knows. So, they need help and encouragement from citizens perhaps much more than many other big-city leaders would need to rely on.

Thanks Michael for writing this. You have a gift for making people excited about changes happening elsewhere in the world!

Oh please… a strong regional mayor? We don’t have one, unless you count the Chair of the Metro Council. Wait, wasn’t that Bragdon?!? More to the point: why we’d ever want to embrace someplace else’s system and culture of governance is beyond me. Do bike advocates really have a need for top-down leaders? And what happens when they leave office and we get a top-down leader for, say, a large, multi-lane bridge over the Columbia? Sorry, but this is not persuasive. Find a way to make Portland more like, well, Portland AND advance your goals for bikes, and then we have something to talk about.

How cool to have Ethan Seltzer weighing in–I love it! And David Bragdon was obviously not referring to his former home of Portland. 🙂 And I’ll stay out of the debates/comments after this, but I was only saying that a mayor in the more traditional system might be able to more effectively advance non-car-dominated infrastructure and budgetary decisions, since we’re all feeling frustrated by how little is being done in Portland on the people-friendly front. It had nothing to do with emulating another city’s system-wide practices.

The point is well taken regarding the risk of having a top-down mayor who advocates for a totally insane CRC (as opposed to George Crandall’s wonderful alternative proposal), but I often feel that it’s worth the risk. At least we could professionally persuade one powerful leader instead of whatever it is we’re currently attempting to do.

Also, I think it’s incredibly enlightening and valuable to see what other cities are doing. They provide real-world test cases on what might or might not work. Plus, they are taking the risks for others, and, most importantly from everything I’ve witnessed, they are demonstrating how unbelievably far behind we are getting when it comes to getting out of the 1950s car-centric model.

However, I totally agree that we need to solve this in a very *Portland* way. That’s our best strength, although our best days in innovating on the transportation and environmental fronts were clearly the early 1970s. Fortunately, we still “Keep Portland Weird” in many wonderful ways (no other city has the food cart culture that we have, although Austin is trying). And no other city I’ve seen or studied has anything like our City Repair. Plus, one word: Portlandia. 🙂

Anything we can do to be unique (as well as, like you said: more Portland!) is incredibly valuable. And there are very easy, Portland-specific things we could do that would have a HUGE difference literally overnight. For example, we have very nearly the highest percentage of urban land devoted to *streets* of any city in the U.S., large or small (due to our 200-foot-between-intersection blocks: GREAT for pedestrians and horrible for biking). Like I’ve told many people, if we converted just 5 or 10% of our urban street space to bike-only use, our bike mode share would skyrocket, and there would be more than enough room for ALL street users (especially those who drive, interestingly enough). There are now dozens of great reports and demonstrations from urban planners around the world that can attest to this often counterintuitive land use (Vancouver’s Brent Toderian is just one of many who has great examples of how constricting auto use benefits everyone). Not to mention other cities, though. 🙂 Plus, I know I’ve mentioned that point enough by now, so I’ll stay out at this point.

Finally, not to advertise another channel (I always try to avoid doing that, but it’s useful in this context), but I can’t recommend the Strong Towns podcast enough; this is where I saw, very clearly mathematically, the huge percentage of street space that we can easily allocate to non-car uses. Chuck Marohn also talks about the perils of multi-billion-dollar “solutions” that often make the problems much worse (hello CRC).

I can’t recommend that podcast enough for learning about transportation and infrastructure issues. It helps me see some very wise, unique to our specific needs, and incremental approaches that we can take in Portland, as opposed to what we see London doing. This can work out well for us because we don’t like to be “spendy” (*such* a Portland term!).

Again, thanks so much for your great comments, Professor Seltzer!

I often share this skepticism, but thought I’d add that Bragdon seemed to be framing his case for a strong centralized mayor as a way to improve public involvement (everybody knows who’s in charge) and internalize the incentives (see item 4 above). Not so much a case for dictatorial power, at least as he pitched it.