(Photos: Aaron Kuehn)

[Publisher’s Note: This is the first part of a three-part series by Portlander Aaron Kuehn. Aaron is the outgoing chair of BikeLoud PDX, a local bike advocacy nonprofit. He recently completed the bikeway design workshop offered by the Transportation Research and Education Center based at Portland State University.]

My name is Aaron Kuehn. I’m a design nerd, and for the past year I was the chair of BikeLoud — Portland’s outspoken bicycle transportation advocacy group. I think everyone has a role to play in designing great streets, so get out your colored pencils and some sheets of paper, and join me as we design our own excellent bikeways…

As Portland savored the last sparkling swigs of Bike Summer, I went back to school for a weeklong Bikeway Design Workshop with 17 transportation professionals to learn how to design better streets for biking.

Summer group rides are a joyful pleasure, with safety in numbers and party vibes transforming almost any street into a great bikeway temporarily. Sustaining that experience year-round, outside a group ride, requires excellent bikeways.

Portland has a reputation as a Mecca for bikeway design. People attend this workshop from around the US to experience our infrastructure gallery in person, and hear from the luminaries responsible. I was there to pry back the craggy layers of Portland’s streets, to scrutinize the design process, and to share what I learned with you.

30% plans – Let’s go!

Let’s start on a 30% plan, just a rough draft of our bikeway, or what someone might refer to as a, “concept of a plan.” If you are feeling under-qualified, buck up! Sixty years ago Jane Jacobs, an activist without a degree or formal training in urban planning, exposed the entire car-centered urban planning field as a destructive and misconceived “pseudoscience.” You are part of the solution.

Things you’ll need:

- Paper

- Extra paper for revisions

- Pencil with eraser

- Colored pencils (especially green), or a computer

- Tape measure

- The MUTCD, or another big book to prop up your final design

Step 1 – Planning to fail

Look at you over-achievers already starting on your road diets — brake check — pencils down. Our new bikeways should work together and build toward a bright future, to catalyze social changes in our community that we desperately need. Before you get started with the fun stuff, read this entire 586-page Metro Regional Transportation Plan first. Just kidding!

Even the Oregon Department of Transportation just starts by drawing pictures of unrealistic hyper-expensive projects that ignore our regional transportation vision: “Everyone in the greater Portland region will have safe, reliable, affordable, efficient, and climate-friendly travel options that allow people to choose to drive less and support equitable, resilient, healthy and economically vibrant communities and region.”

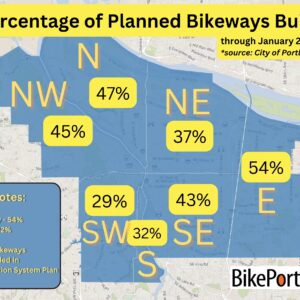

Portland also has a 20-year Transportation System Plan, and a Bicycle Plan for 2030. The objective of the Bicycle Plan is to enable 25% of trips to be made by bike! The rosiest internal assessments show a long ride ahead.

Don’t let strategic planning, or a lack of progress on regional goals stand in the way of your design process. Your project is underway and the clock is ticking.

Step 2 – The user

Once you get the hang of drawing bicycles — which is the hardest part of bikeway design — you are going to want to show people riding them. But what kind of people? Portland’s long-time bicycle coordinator in a fedora, Roger Geller, wrote a legendary paper that first identified the four types of bicycle riders. He postulated most people are “interested” in bicycling, but also “concerned” about its safety. The bicycle riders in your design should look “interested but concerned.” You should also show riders of all-ages-and-abilities, which should get your creative juices flowing.

Acknowledging that our designs must facilitate all kinds of people to ride bikes opens up new design options. Your bikeway can be anywhere on the page now, not just squeezed over to the right by the parked cars, where only the ‘strong and fearless’ dare ride.

Step 3 – The network

If you are doing a perspective drawing of your design, or even a cross-section, you will need to show some context for your bikeway. Does it connect two parks or neighborhoods? Is it a way to get to school, or to the store? Which streets will your bikeway traverse?

With 55,000 streets in Portland, if each street segment was a brain cell, the network would be as complex as a slug brain. Slugs aren’t very smart, but they can design transportation networks — using desire lines.

Like slugs, bicyclists leave a shiny trail behind that can be observed in the right light. Location based services on phones, e-scooters, or bikeshare show the popular street segments and routes that people actually prefer – the slug trails. Lots of slug trails are on streets without existing bikeways, or on streets with bikeways that need a refresh. Pick one of those “desire lines” for your bikeway, and you will be ahead of state-of-the-practice designers.

Step 4 – Political willies

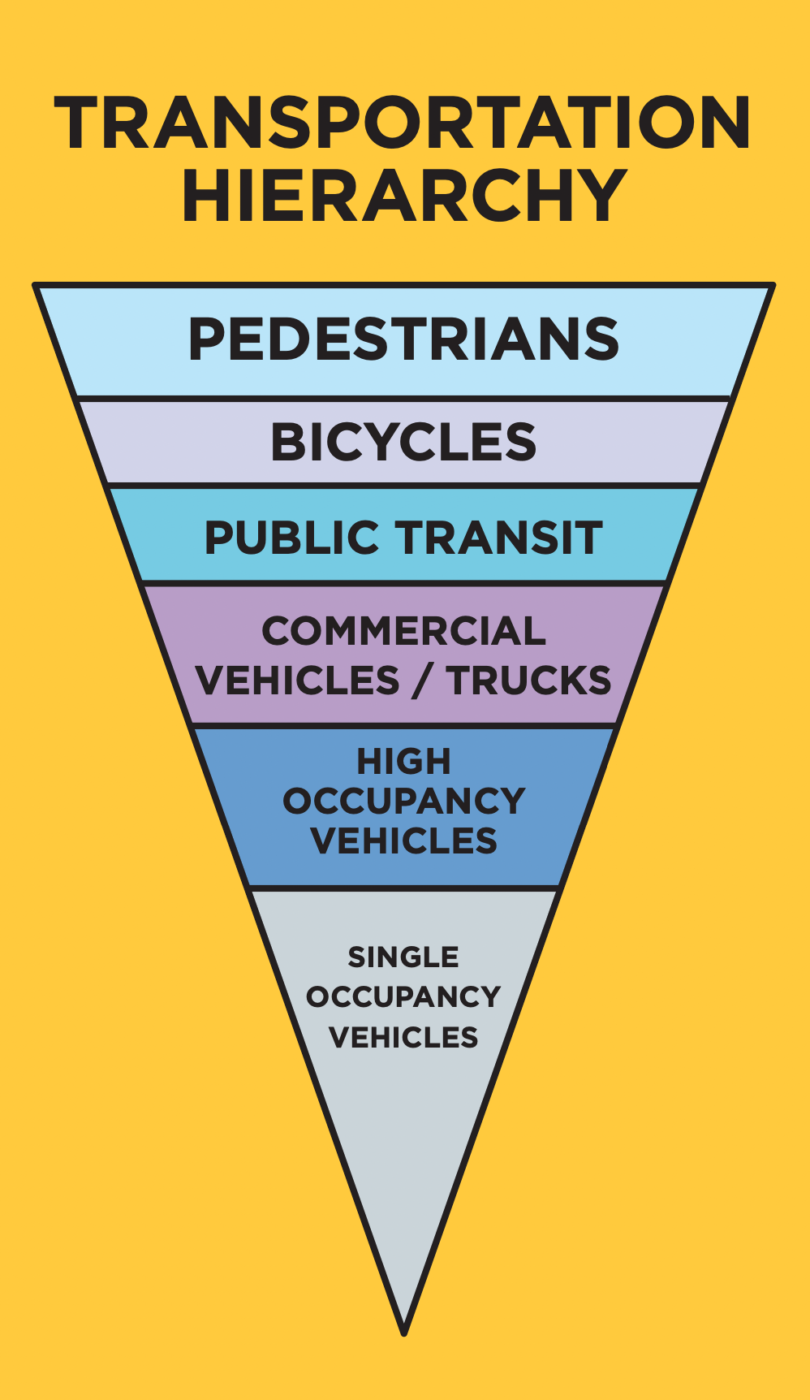

Drawing bikes and people is hard enough, does your design need to show cars too? Portland answered this in the 2009 Climate Action Plan. According to the “Green” Transportation Hierarchy, people walking and riding bikes should be the most prominent elements in your design, and cars should be considered last.

If you don’t show cars at all, people might get offended and say your design doesn’t look like a real street. You might hear there is not the political will to build your design, or there is no reason to build a bikeway without the traffic volumes to justify it.

The hysteria and passion people have for defending driving is a result of motonormativity, where attempts to reduce car use are interpreted as an attack on personal freedom. Because motonormativity is prevalent not just in drivers, but pedestrians, cyclists, transportation engineers, and throughout society — if your design doesn’t show cars you’ll have some explaining to do.

Set up at least one meeting with community members and other stakeholders to gather their feedback. Engineers still use the Decide Announce Defend (DAD) strategy during community meetings to ward off costly revisions, but you can use sticky notes, a multilingual survey, or other engagement tools to capture public sentiment.

Another way to involve the community in your design is to invite them to participate, or even make budget decisions. Sincere dialogue between project partners, like the City and the public, builds trust and begins the process of identifying the real interests that underlie our steadfast positions. When our real interests are identified, it’s easier to create designs that successfully respond to them.

Step 5 – Fieldwork

If at any time you feel stuck, or just need to exercise your legs, go out into the field for a site visit. Riding your bicycle is an important part of the design process. Imagine you are a real person riding on your future bikeway, what would you want? You can tell when a bikeway is only designed on paper — go ride it!

Our 30 Percent Plans are taking form. In the next part we’ll move onto 60% plans and incorporate the community feedback we received and make some big decisions using standards and best practices.

— This series is by Aaron Kuehn, a veteran cycling advocate, Bike Happy Hour regular and former chair of BikeLoud who rides a Marin Pine Mountain with hi-viz streamers. Read the full series here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

One radical idea I’d like to see more of is the following:

Let’s take all of our existing roads, cut them in half, and make travel one way for cars and trucks. The other half will go to bikes, peds, and transit. This way you save trees. which we desperately need – you can’t keep widening streets ever further to add bike lanes, MUPs, sidewalks, etc.

Out here in SW Portland where I live, this is the only way to achieve any meaningful infra for bikes and peds. I hope city leaders are listening.

Hamburger style 🙂

I agree. It doesn’t even have to be “all” our roads. A handful here and there could make an absolutely amazing bike network with very little impact to automobile access.

I disagree. One-way routes would simply encourage car drivers to drive in the bike and pedestrian lanes, faster, and the police never bother to enforce any law or street design they themselves don’t like, plus you still have to deal with driveways. I think a better solution would be to reduce the posted speed limit to 20 kph (about 14 mph), remove all yellow striping and all stop and yield signs, add parking lines on alternate sides of the street to create a chicane effect, and reduce any 4-lane stroad to one lane each way, no yellow stripes nor center turn lanes, and take away traffic lanes and replace them with concrete barrier-protected bike lanes, and walk lanes where there are no sidewalks.

Fred,

There is a proposal just like that floating around that is pretty cool! These big idea visions benefit from community support, input, and feedback: https://bikeportland.org/2023/10/05/urban-trails-a-bold-plan-for-the-next-generation-of-portland-bikeways-380055

Thanks Aaron! This is much needed.

“Like slugs, bicyclists leave a shiny trail behind that can be observed in the right light.”

Oh man, that one got me!

I take issue with step 3: Desire lines. It is important when doing fieldwork to study and acknowledge how people are currently moving around, but that needs to coupled with a an inventory or obstacles, missing infrastructure or or negative impulses that impact how a person instinctively moves around. Its like the quote ‘You can’t justify a bridge by the number of people swimming across a river‘ you shouldn’t design a bike route based on desire lines because you may be missing the transportation need. In other words desire lines may simply show what people want to avoid rather that where they want to go. I would also like to plug a few design principals for designing bike routes that PBOT often overlooks:

Excellent points maxD. I would add that tracking where most people on bikes go (e.g., the strava heatmap) is an example of a survivorship bias. Sure, it’s one of many good tools to use, i.e., an indicator. But it’s has its complications, for example, the type of people who use Strava, and the purpose of their rides etc.

When building a network we need a simple (intuitive), functional (direct), and safe system geared not towards people using an app, and certainly not exclusively based around the preferences of people who are currently using the system (which skew male and athletic), but towards the vast number of people who don’t bike or bike infrequently because our current separated network is neither simple, functional nor safe.

Great points! The bridge metaphor is especially true when the bikeway is literally a new bridge. The Blumenauer Bridge, for example, opened up new routes and new desire lines that were inconceivable before it existed.

Strava Metro, which I do use for observing “desire lines,” does skew toward certain demographics, less than you might think though.

The Location Based Service I linked to in Step 3 is Ride Report, which by incorporating e-scooter data and bikeshare data, skews instead toward those populations we are more interested in prioritizing, people who don’t bike or bike less frequently.

For example, the large amount of users observed riding e-scooters and bike share presumably on the sidewalk on 82nd Ave, to me shows a strong “desire line” case that there should be some type of enhanced accommodation for those users. Strava users by contrast, like you point out, are less likely to bike directly on 82nd. LBS tools aren’t the only measure of desire, and each one individually has its quirks. They are like you say, convenient tools to use as indicators, especially when you also consider the demographics they are likely to represent.

The problem with just building what we presume to be intuitive, direct, and safe networks, without using observation tools, is that we are massively over valuing our own biases about what is intuitive or direct for us. I love to see usage patterns that surprise me, routes I would never consider, or data that doesn’t conform to my expectations. When we choose to observe those patterns of desire, we are beginning the process of empowering the users to design the system, even if it is only a subset of the users.

It’s also excellent to understand that all this is work in progress. Desires change and adapt, as people change and adapt. LBS and other tools are especially good at observing trends over time, even hour to hour. With construction projects, street closures, and a city in motion, there are ‘natural experiments’ happening all the time. Having measuring tools already in place, on every street, gives us the ability to use retrospective observations of these experiments to make more informed design decisions.

I agree with your points about “Safe” and “Connected”, but I disagree with “Simple”. A lot of design criteria are borrowed from car culture, which Aaron alluded to as being so dominant that it even permeates bike route designers. In those cities where car routing is “simple”, car drivers drive faster and non-car users are put in greater danger – the most extreme example being freeways. In those (rare) communities that have really complicated car infrastructure, with frequent changes in lane width, number of travel lanes, shared bike or bus lanes, frequent crosswalks, parking types, no parking, etc, (car) traffic moves much more slowly, really no faster than the freight truck or bus in front of it, particularly when scooters and bikes are actually mixed in with the car traffic – think about downtown streets, but even more notorious are “college town” main streets in much smaller communities, where lots of pedestrians are crossing every which way. “Simple” bikeway designs more often encourage car users to move faster.

I strongly recommend the #5 Fieldwork to include visiting other towns and cities and see how they did it, not just physically, but talk with local city staff, advocates, and the press about the projects to see how it was done politically. You need to recognize that no matter what community you live in, someone else somewhere has done it better. It’s also good to learn from other’s mistakes and why a design didn’t work, worked in the past but doesn’t any longer, or why sometimes doing nothing is a better option.

Another great point. Step 11 in Part 3 of this article will cover design principles, their importance, and why PBOT often overlooks or reduces them in more detail. Stay tuned…

All bikeways and infrastructure are designed and built in a political context.

One of the BTA’s (the Bicycle Transportation Alliance of Portland) greatest achievements was the coordination of a concerted advocacy campaign around the creation and adoption of the 2030 Bike Plan. Although the follow up momentum surrounding Build It / Fund It lost momentum as it’s champion Sam Adams got derailed by scandal, for that moment and never since then has it felt like all of the institutions and efforts in Portland were aligned to support municipal bicycle transportation infrastructure.

Of course there’s a world of change, including the good (better Natio) and not so good (Lloyd to Woodlawn Greenway) since then that has happened and will continue to happen and real political obstacles to achieving support for safe, connected bicycle transportation infrastructure.

I very much appreciate BikeLoud and it’s many grassroot efforts. But I also want to acknowledge the gaping hole on the local political front by no longer having a staffed professional bicycle advocacy organization in this town like the BTA. I don’t currently see that kind of organization in Portland.

As we approach a new form of politics in Portland with the coming election we would get alot of mileage out of such an organization helping to steward our elected leaders and their hired administrators toward planning, funding and building the next chapter of bicycle transportation infrastructure.

You are absolutely right twenty-five percent plans. NYC has Transportation Alternatives, which is a gigantic, well funded non-profit, that has an enormous effect on the outcome of local bills and media exposure. BikeLoud is still all volunteer I believe. Without a well-funded non-profit willing to take direct action when, for example, a council member wishes to remove a separated bike lane on SW Broadway, we rely on ad hoc and volunteer organized groups without a single vision. This is likely one of the many reasons why Portland has been spinning its wheels without any real momentum for decades.

I also totally agree, and really appreciate the entirety of your well constructed comment. I am happy to inform that BikeLoud will be contracting it’s first part-time non-volunteer starting this fall. This PCEF funded staff person will be dedicated to the BikeLoud Bike Buddy program, but it begins the process of having staff at all, which is a big jump. Contracting a second staff person is now a high organizational priority.

BikeLoud is the work product of a growing circle of very passionate, skilled, and dedicated volunteers, and has historically been funded entirely by member donations, which ensures the political power and flexibility other organizations seem to lack. BikeLoud doesn’t always take credit for everything that is accomplished because volunteers are busy doing the work instead, but when Portland’s wheels do get traction it’s often on BikeLoud grit. Maintaining independence as BL seeks additional funding is tricky but seen as essential.

BikeLoud’s member donations will need to increase to reliably cover even one part-time staff person, without compromising the ability to stay loud. This won’t bring BL to the level of Trans Alt, which is an unrealistic but inspiring comparison, but it will help to ensure organizational stability to consistently engage on long-term projects, which will likely have a noticeable impact. You can donate here: https://bikeloudpdx.org/donate/

That’s great news! BL is invaluable to Pland, and I assume often takes a rather thankless role. This may be beyond BL’s capacity, but TA has a system of campaigns that are a mix of advocate- and TA- in origin. These focus advocacy on one specific goal (e.g., NE Broadway/Weidler) and get frequent communication going between advocates and local council members for that one goal. And if people ask “What are you working for?” that can be a solid answer. I think it’s a possibility here.

I agree with your comment in some respects. I don’t think the community fully understands what it meant when The BTA changed its name and stopped doing on-the-ground, in-your-face, reactive work like they used to do. It was a massive shift and nothing took its place. BikePortland became the lone loud voice in this space in many respects, until BikeLoud began to step up. But yes, BL are still not able to be what The BTA was for various reasons.

I’ve always thought that if I was in charge of The Street Trust when BikeLoud first started having meetings, I would have offered to bring them into TST so that we’d have one, stronger group that could do all types of advocacy and have the benefit of TST legacy and funding heft. Sort of like an older company might gobble up a startup to stay relevant or something like that.

But now I’m glad BL and TST aren’t connected because BL has a real shot to become something special and I’m not sure I know what TST wants to be.

You have completely missed one of the most important parameters – why. Why do people ride bicycles? There are casual riders, kids, and those who occasionally want to get out on a nice day. There are recreational riders, out for a regular workout. Then you have commuters. I can assure you the reason the last two types don’t use bike paths in Portland is too many stops signs. If you’re trying to keep your heart rate up, you cannot stop every other block. If you’re trying to get to work, you will take the fastest route, not the one the that doubles your time en route hunting down as name stop signs as possible. Given that Portland is hostile to cars, in favor of bicycles, you should design a bicycle route system that gets cyclists, even timid one, to their destination safely and efficiently.