— This story by Jamie Mathis originally appeared on OregonMetro.gov.

On a late summer morning, the sun is just starting to heat up the parking lot at Newell Creek Canyon Nature Park as three bicyclists get their gear together to hit the trails.

There are the standards – helmets, bike gloves – and then the bikes themselves, which are anything but standard. The three-wheeled vehicles sit low to the ground, with the rider’s legs stretched forward to the front and are strapped in, similar to a recumbent bicycle without pedals. One has a chair-like seat; another has a saddle that tips the rider forward over the front two wheels. These are adaptive mountain bikes (aMTBs), designed to allow people with disabilities to ride on rugged terrain.

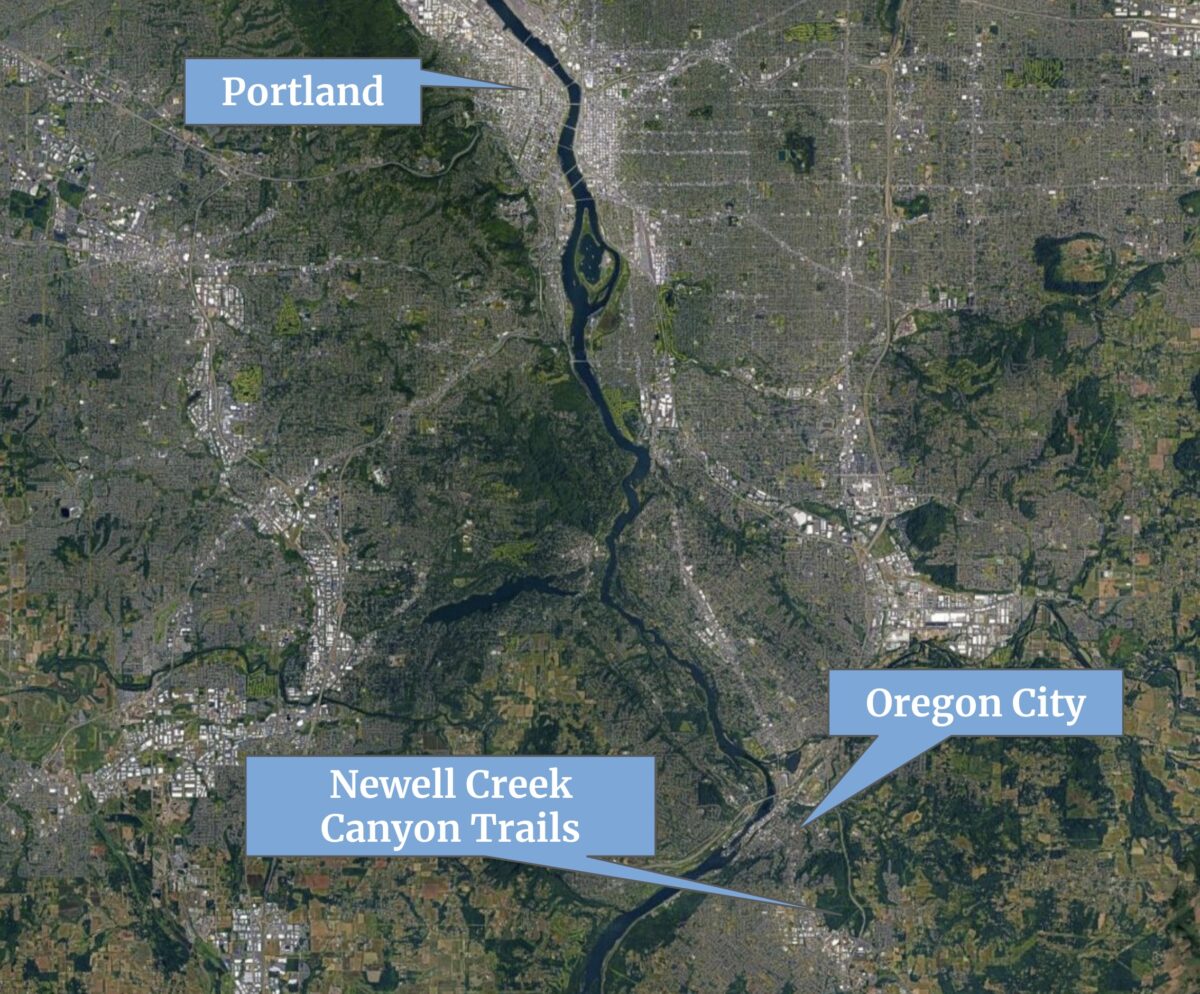

“The huge battle is getting trails we can actually ride,” says Kipp Wesslen, who works for Washington County and has quadriplegia. “This is one of the first places that has had some thought around accessibility put into place. There aren’t that many places within easy distance that we can ride, either because of gates, trail width or camber.”

“The huge battle is getting trails we can actually ride, this is one of the first places that has had some thought around accessibility.”

— Kipp Wesslen

Indeed, until recently even Newell Creek Canyon had a barrier for aMTBs. While the trails had been designed for all-access passage, the gate to the trailhead had been made to have a narrow opening, just enough for an upright bike or baby stroller to pass through – a standard park practice, designed to keep motorized vehicles off the trails. But that opening couldn’t accommodate the much wider wheelbase of aMTBs, which can be upwards of 40 inches.

Max Woodbury, a mapping specialist at Metro who became a quadriplegic in his 20s due to a spinal-cord injury, says that the first time he visited the park, he needed to ask a ranger to unlock the gate in order to start his ride.

“That’s not really accessible,” he noted wryly.

When the park opened, Metro hired a contractor to test the aMTB accessibility of its trails and discovered the issue with the gate. At first, it seemed like it would be a complicated fix requiring a new gate. But park rangers innovated a way to winch the existing gatepost away from the gate, creating a wider opening. Today is the riders’ first time biking the park since the gate has widened – the moment of truth to see if the rangers’ solution has worked.

Once everyone is strapped in and ready to ride, they roll through the gate and pause at the top of the trail. “That’s awesome,” Wesslen notes as each bike cruises easily through.

They start onto the Red Soil Roller Trail, a series of winding switchbacks, which brings smiles to their faces as they prepare for the challenge ahead. Wesslen goes first. His bike allows him to lean forward, with his torso braced by a bucket seat and shin supports.

“You can do a lot of technical stuff on this style aMTB,” says Wesslen. “Anyone riding this has the ability to shift their weight, which makes it better for downhill. It gives you almost the exact same feeling as an upright bike.”

Adaptive bikes aren’t cheap, costing upwards of $8,000 and often closer to $15,000. Thankfully, some nonprofits offer grants to help make equipment more affordable, and the riders say the sport is growing. They generally are able to organize rides at least once a month during good weather.

Along with Wesslen and Woodbury, today’s group includes aMTBer Loehn Morris. He follows Wesslen, successfully navigating a steeply pitched turn. He whoops coming out of it and flies off down the trail to give Woodbury space to attempt the switchback.

“I went over on this berm last time,” says Woodbury. Spills are one reason why many aMTBers bring an able-bodied biker with them on rides – today, it’s Jean Perkins, a musician and caregiver to Woodbury. She follows the three aMTBers on her upright bike.

Woodbury pauses and studies the trail, debating how to best enter the turn. After talking through several options, he decides to just go for it and see if he can stay upright this time, saying, “Well, this is what makes it fun. It’s challenging.”

Maple trees shade the trail, an important feature for many adaptive bikers. “Temperature regulation is a huge issue because if you are a full-on quad you don’t sweat,” Wesslen explained. “If you get over-heated you can go into dysreflexia, your blood pressure spikes – it’s bad. You typically don’t sweat below the injury site. Being in shade absolutely helps.”

Adaptive bikers have other unique challenges. After several switchbacks, the riders approach a plank bridge with bumpers that are too close together for them to pass between. Their work-around is straddling the bumper and having an outside wheel on the overage that isn’t more than a couple inches wide. One biker rides his outer wheel up onto the bumper and rolls at a cant across the bridge.

Because trails often have hidden hazards like this, aMTB riders take a cautious approach. Before going down a section of trail they don’t know, they queue up and study it piece by piece so they can figure out where the pinch points are, like a steep berm or a rock. Then they decide which moves they need to make the maneuver successful. The goal is to be able to take it at speed on the next lap for the thrill that’s common to all extreme sports.

That’s not always possible. The trails at Newell Creek Canyon are popular enough that a Saturday ride can feel a little like being on the highway at rush hour. As the group lines up to navigate some downhill berms, a biker zooms by them at top speed, creating yet another hazard for them to navigate.

Morris reflects on an ideal environment: “I want a trail where my wheels are totally fine the whole time. This is one of the best, most accessible trails close in we have in the area.”

The riders roll back up the hill to the parking lot, using their e-assists to help with the incline. Each can pass through all sections of the trail, gate and parking lot.

The day’s heat is kicking in and it’s time to go home. The riders strip off their gear and load their bikes back into their vehicles. “Let’s get another ride together soon, guys,” says Woodbury, and the others cheerfully agree.

— Jamie Mathis, Metro

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Let’s hope Metro gives the same thought towards the trails at North Tualatin Mts, if they ever get built. Glad to hear eBikes (at least class 1) are allowed at Newell.

Yikes, that first photo with the trike wheel on the edge of the bridge really illustrates the struggle

Thank you for publishing this article! I have now discovered you published multiple articles on Accessibility cycling. I have a dear friend, Dave, who suffered a Severe TBI as I did, and he is slowly healing and has returned to Accessibility sports. Including a tricycle, rock climbing, and skiing (with assistance). Dave would like more accessibility cyclists to ride with.

I also have a friend who is now a quadriplegic after his injury. He would like more information on the type of bicycle Woodbury is using. And maybe I can connect them?

You mean “trikes”? Bikes have two wheels; trikes have three.