It’s always fun to see the Tilikum Crossing bike counter tick up as you pedal across the bridge, checking out how many other people have biked on the same route that day. But bike counters are an important tool beyond just novelty. People working to plan bike infrastructure projects – and acquire government funding and political support for them – need to know how many people are biking and where they’re going. In order to do that, they need to make sure they’re getting the most accurate count possible.

There are many tools to count bike trips; but each of them has its drawbacks. Ones that use smartphone data from apps only capture people who use them (and that have phones). Bike counters like the one above are expensive and don’t scale (they are also easy targets for vandals).

It’s a problem that has plagued cycling advocates for years; but researchers from Portland State University’s Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) think they might have a solution. They call it “data fusion.”

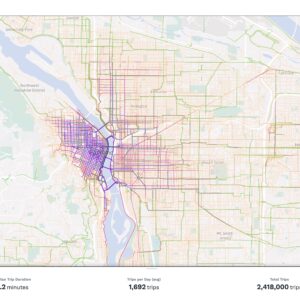

A project team led by Dr. Sirisha Kothuri wanted to find out what happens when data from different tools are mixed. Their work was based on the idea that a more accurate picture of cycling traffic can be made by combining, “traditional and emerging data sources.”

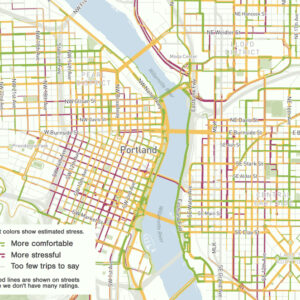

The team looked at three newer “big data” sources — the Strava smartphone app, Streetlight Data (and analytics firm), and GPS figures from bike share systems — in six cities (Boulder, Charlotte, Dallas, Portland, Bend and Eugene). They fused that data with more traditional bike counters cities have used for many years.

They then created three location-based models to run the data through. “In general, the various data sources appeared to be complementary to one another; that is, adding any two data sources together tended to outperform each data source on its own,” reads the project summary. The findings from this study indicate that rather than replacing conventional bike data sources and count programs, big data sources like Strava and StreetLight actually make the old ‘small’ data even more important.”

“At ODOT we just adopted ‘Bicycle Miles Traveled’ as a new key performance measure, and we need a way to measure it, so this project very much helps to fill the gap on how we’re going to do that.”

– Josh Roll, ODOT research analyst

Oregon Department of Transportation Research Analyst & Data Scientist Josh Roll sat on the project’s technical advisory committee and said the insights could help his agency get a better grasp on how well (or poorly) they’re serving bicycle riders. “At ODOT we just adopted ‘Bicycle Miles Traveled’ as a new key performance measure, and we need a way to measure it, so this project very much helps to fill the gap on how we’re going to do that,” Roll said in the project summary.

While creating this report, researchers uncovered another problem: despite support from agencies and jurisdictions, gaining access to the bike count data was difficult. Researchers noted that agencies appeared disorganized and were using questionable tactics when deciding where to place permanent count mechanisms, tending to “locate permanent counters in clusters of similar location types, resulting in little information about bicycle activity in different contexts.”

Portland is doing this better than most cities. The Portland Bureau of Transportation brought back its annual short-term bike counts this summer and Biketown has a transparent and robust data dashboard.

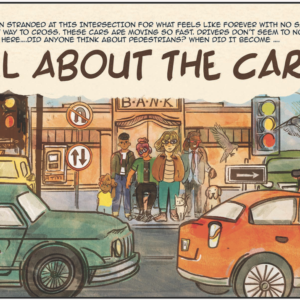

The lack of accurate bike counts and ongoing challenges in accessing the data are yet another way our system tilts in favor of car drivers. If we want to get more people on bikes and save our cities and our planet in the process, we’ve got to up our game when it comes to non-car traffic counting.

But don’t just take our word for it: “For transportation agencies wishing to support active travel to meet various sustainability, public health, and climate- related goals, quickly having accurate data for the entire network would be a giant leap in the right direction,” the report says.

Learn more and view the full report here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

They also need to consider adaptive bikes. Every time I’ve ridden my recumbent trike across Tilikum I never trigger the counter, but my upright bikes do. Very frustrating to miss out on data for the adaptive cycling community.

Strava data has a problem of capturing almost entirely sport-cyclists as opposed to people running errands, commuting, going places etc. I wonder if Google/Apple maps have better data that can differentiate between when someone is biking vs riding in a car (I know Google maps can at least differentiate between car trips and motorcycle trips based on the acceleration felt going around corners). Trying to collect good bike/ped data could make the case for Trimet to make their Trip Planner webpage into a proper app so that they can collect the data that way and share it with Metro transit agencies.

I think this is a misconception. While it may not represent the larger Strava userbase, many people I know use the app almost exclusively to log commutes/errands. Regardless of the intentions of the user, I think the Strava Metro data can be a useful tool for urban planners.

However, it only tracks those wealthy enough to subscribe to the service so isn’t going to be at all useful for those that don’t.

I get that we need numbers and counts to manage the motorized vehicles on our streets, but the bike network design should not be relying too heavily on counts, IMO. WE have a woefully incomplete network. What we have is riddled with holes and gaps and dangerous segments. This design is much more map-based. We know the areas that need connections, we should be focused on creating simple, direct and safe connections. The counts of people biking are inherently flawed: you cannot count the people who WOULD be using the bike network if the network was complete.

I just think it’s incredibly rad that someone working for ODOT is named Josh Roll.