(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

At long last, Portland has an official guidebook to build out its protected bike lane network.

If you’re feeling a bit of déjà vu, that’s because we excitedly shared this same news back in June of 2018. But for some reason, after it came out in draft form, the guide was scrubbed from the Portland Bureau of Transportation website pending more internal reviews. Many advocates were excited when the guide was set for City Council adoption in September 2020, but (former) PBOT Commissioner Chloe Eudaly and PBOT leadership scuttled that plan at the last minute due to concerns over racial optics. I’ve been hounding PBOT ever since about when it would be released, and then lo and behold, I just happened to stumble upon it on their website a few days ago. It looks to have been finalized and published in May 2021.

More of the backstory here is that the PBOT has not built enough protected bike lanes to entice the masses to ride. Portland has built just 38 miles of protected bike lanes — less than four miles per year — since 2010. One of the reasons we’ve been given for this glacial pace is that PBOT staff (engineers, planners, project managers) haven’t had an official guidebook to work from. If you know anything about how government works, you know that in order for things to get built, staff must have guidance to not only help them understand what to do, but also to absolve themselves of legal and/or political fallout if things don’t turn out well.

In the U.S., engineers are trained with guidebooks from the Federal Highway Administration and state DOTs, and have only recently been using a more progressive one created by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO). But none of those resources have the detailed, hyperlocal knowledge necessary for city staff to confidently implement protected bike lanes right here in Portland.

That’s where the Portland Protected Bicycle Lane Design Guide (PDF) comes in.

Why does this thing matter? Because like I shared above, it gives city staff an authoritative source for decision-making. This guide offers detailed cross-sections, data, and insights that give engineers, project managers, and planners the ability to simply plug-in their street characteristics and see what type of protected bike lane design is feasible, how to build it, what to consider when doing so, and how much it’s likely to cost.

Speaking of cost, the detailed breakdowns of how much money it will take to build a protected bike lane network are one of the coolest parts of the guide. PBOT says costs range from $73,000 per mile to build parking-protected bike lanes (on one-way roads) to $1.1 million per mile to install concrete island-separated bike lanes on a two-way road.

Here are some other key nuggets in the 125-page guide:

Advertisement

— PBOT addresses maintenance issues by saying they are still trying to find a sweeper that can get into five-foot wide protected bike lanes (the narrowest variety). The guide also addresses access considerations for mail delivery, garbage bins, and delivery vehicles.

— The guide says PBOT’s preferred width of a one-way protected bikeway is 6.5-feet of clear space in the “bicycling zone” (not including a buffer or necessary shy distance, both of which are explained in detail). 5-feet is the absolute minimum and should only be used where there are less than 150 riders per hour at the peak. If there are more than 750 riders per hour, the preferred width shoots up to 10-feet on a one-way street. For bidirectional bike lanes, PBOT sets a minimum of 10-feet and a maximum of 16-feet.

— As frustrations mount about the use of cheap and frail plastic wands, some of you might find comfort that PBOT acknowledges the issue in the guide. “Jurisdictions across North America that rushed to install protected bicycle lanes with delineator posts are replacing them with more permanent materials,” it reads. “Delineator posts may require frequent maintenance if they are hit often. For example, some of Portland’s existing delineator protected bicycle lanes require replacement of approximately 10% of installed posts every six months.”

— One detailed I loved to see was how PBOT understands the problem with low-hanging tree branches. Because many protected bike lanes create a bicycling zone where there typically isn’t one (next to the curb), they state in the guide that, “once [the curb zone] becomes a bicycling zone, low-hanging branches and other intruding foliage present a hazard to people bicycling.” PBOT says trees must be cut to a minimum height of 11-feet above the roadway.

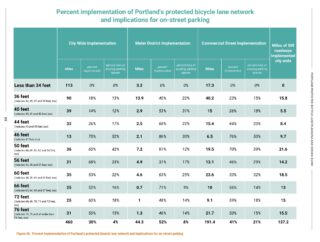

— Parking removal gets a lot of attention since it’s often the #1 controversy when building protected lanes. The guide has a detailed spreadsheet (above) about how much car parking is estimated to be needed to build all the different types of designs. To put it into perspective, PBOT estimates that if they build just 30%, or 137 miles of the 460 total miles of protected bike lanes Portland needs, it would only result in a loss of 4% of the overall on-street space currently used for parking cars. They also break that number down for meter districts, where half the proposed protected bike lanes (about 44 miles) would result in a loss of 8% of metered parking spots. And in commercial districts, if we built 41% of the 191 miles of protected bike lanes called for in our existing plans, it would result in a reduction of 21% of existing on-street parking spots.

— Back to costs, if PBOT built out a majority of these 137 miles of protected bike lanes with plastic delineator posts, it would cost just $57 million. To retrofit street with 4-foot wide concrete traffic separators, the cost is about $1 million per mile. These figure are “fully loaded”, meaning it has a 2.5 multiplier over construction costs that takes into account design, administrative staff, and so on.

According to League of American Bicyclists Policy Director Ken McLeod, guides like this one are “rare”. He says none of the other top cycling cities in America like Madison, Boulder, or Davis have such detailed operating instructions for protected bike lanes. Their plans usually just reference national guidebooks like NACTO’s Urban Bikeway Design Guide.

There’s a ton of great information in this guide and we hope it becomes a powerful tool for both PBOT staff and advocates alike. We have just removed one of the main excuses for not building protected lanes. So let’s get to it.

One last thing: The completion of this guide would be a great excuse to get cycling some attention in City Hall. I’ve asked PBOT if they plan to present it to council for adoption and will update this story when I hear back.

If you’re wonky and you know it, click here for the PDF.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

A quick question – is there anywhere in there guidance for deep set storm drain gratings in the protected bike lane (or, more accurately, *not* having them?).

I can *almost* keep my right wheel from dropping in the ones on BHH just past Oleson heading towards town – but I have to skim wand bases with my left tire. On Bertha with no wands I just spend most of my time with my left wheel outside the lane. On non-“protected” bikelanes with a buffer I just run the left wheel in the buffer.

This is one of the reasons I’m not fond of the protected bike lanes PDX has been installing. My width is 32″ – I should be able to ride in a 5′ wide lane without massive jolts from hazards on the right side of it.

Before anyone comments about them not being designed for 3 wheels – a trike meets the state definition of a bicycle allowed to use bike lanes.

Yes. See page 34 of the guide:

Excellent – Thanks!

Too bad this storm grate guide wasn’t around when they repaved Tillamook through Hollywood.

…or just about any other street in town.

Note the word “should” rather than “must” – it’s advisable but not required to have the right grate.

Sounds great on paper, but when are they going to retrofit the thousands of hazardous drainage grates on existing facilities?

Once upon a time they said they would stop using double-wide drainage grates but that never happened either.

Trike Guy, are you the one that designed the cool trike (Bill)? Cool concept.

If they make you ride in a bike lane in the gutter, protected or not, there will always be hazardous drainage grates no matter what the city code or the engineering standards say. One more reason I will never use these facilities! Drainage grates, poorly repaved utility cuts and other pavement and ROW hazards are concentrated in them.

This looks very promising! Lets hope PBOT will use these to fill in the Skidmore Gap (between N Michigan and NE 7th)!

The two issues I have with protected bike lanes relate to maintenance or, more specifically, the lack thereof. Protected bike lanes appear to be seldom, if ever, swept. Second, plastic wands disappear at an alarming rate. There appears to be no interest in replacing them. There are blocks of SE 45th where no plastic wands remain! Overall, I’d guess half are missing for the entire segment.

If we can’t maintain it and make it safe to use, is it worth the expense?

Is PBOT’s long-term goal to have all bike lanes moved up to sidewalk level?

My experience is that having the bike lane at a different level is good between the sidewalk and bike lane but less important between the general travel lane. If there’s a barrier it can be the same level as the street. People walk around and if the bike lane is the same height they’ll walk into it, with a curb they won’t.

It’s cheaper to just put in a barrier and leave the existing asphalt than to add asphalt to a higher level.

For those curious to compare cities’ plans, Vancouver, BC follows the NACTO guidelines as well as Canada’s TAC guidelines but also, like Portland, has made some of their own.

This is a simple guide.

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/design-guidelines-for-all-ages-and-abilities-cycling-routes.pdf

Complete streets policy framework for AAA cycling routes

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/complete-streets-policy-framework.pdf

Catalogues of protected bike lanes (3 years old, in 2 parts)

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/protected-bike-lane-catalogue-part-1-one-way-bike-lanes.pdf

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/protected-bike-lane-catalogue-part-2-two-way-lanes-and-pathways.pdf

I’d rather have pedestrians occasionally wandering into the bike path than vehicles parked and left there for hours, which already happens in Portland’s “protected” bike lanes.

I’m impressed with this guide as well as the updated traffic design manual volume 1: https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/751333

My community is redesigning a major ugly and proven fatal stroad called West Gate City Boulevard, 65 feet curb to curb. I’ve already forwarded Portland’s recommended designs to our various transportation key gate keepers. Using the valuable tables on pages 102 and 103, the cost to retrofit barrier-protected bike lanes ought to be no more than $2 million for the 1.8 miles that need improving, and not the $11 million local estimate.

Please don’t spread Portland’s poor design standards elsewhere!

On the concrete island protected lanes, why is it that a 10-foot auto travel lane gets a 1-foot shy zone, which makes it an 11-foot lane, while a 10-foot bike lane doesn’t get an added shy zone, making it really a 9-foot lane?

We all know which vehicle is at greater risk from accidentally scraping against the concrete island…

The low hanging trees are already a substantial problem for those who ride stand-up bikes.

Less and less people are biking in the city. It seems like we are spending lots of money on things that don’t help most of Portland. And congestion gets worse. Why do a very small group now get all the bridges, lanes, protected lanes, and laws that are one sided?

so what do you propose the money such as it is gets spent on? For example, bike infra is a whole lot less expensive than highway expansions, and no doubt better for the climate also.

Have you ever seen anyone biking on the Fremont or Marquam bridges? Or anyone biking in any lane on any Portland freeway? Which laws are “one-sided”?

I thought PBOT had the mini sweeper for bike lanes? I’ve never seen it, but it’s existence and operation has been reported on BP.

Yeah they have a super small sweeper but either they are choosing not to use it or it’s still too big.

With City Hall still closed and all staffers still in the WFH mode it seems like not much is getting done. Schools are open, libraries are open. Target is open. It’s time to open City Hall

In what universe is working from home not being “open”?

There are a lot of reasons to complain about City Hall, but staffers working from home for theirs’ and others’ safety is not one of them. I can call or email staffers just as easily (and usually more quickly and efficiently) than I could have gone into meet with them.

The manner in which this “guide” dropped — as if PBOT is embarrassed to publish it — is not something to celebrate. Moreover, the fact that the council never bothered to vote on it suggests that its impact will be negligible — PBOT’s leadership take their cues from the politics of the current city council not from the piles of “plans” and “guides” rotting on shelves in their sub-basement storage room of failure.

I also think the unchallenged acceptance of PBOT’s “38 miles” is wishful thinking. I expect many of these “miles” include ped facilities where people on bikes are allowed to share some space (which is hardly ideal for people walking or cycling).

I’d like to see the planter with parking option (apoligies if I missed it in the document). Those plastic popsicle sticks are not the best looking and seem to break into little pieces destined to be washed into the river. Maybe some water-filled barriers could be a good option to gauge placement/ flow and then move to the more permanent concrete? See my link if you like. Cheers, D

A quick review of the guide shows no mention of jersey barriers – real protection IMO. They’ve been used in Portland before, as on Greeley, and I’d like to know why they weren’t included in this guide?

I see the guide relies on the federal definition which cites “vertical elements” as protection. That’s beyond weak.

Jersey barriers ought to be an option – indeed, a preferred option – if safety is not be trumped by cost, drainage, sweeping*, and all the other considerations that make this work challenging.

Seriously, the only design I see here that is truly protecting vulnerable road users is parking-protected … the irony of being protected by parked cars should not elude us!

* – why can’t someone come up with a sweeping solution?! [cough, cough]