(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

“This incremental change is not good enough… we are failing as a state.”

— Hau Hagedorn, chair of the Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee

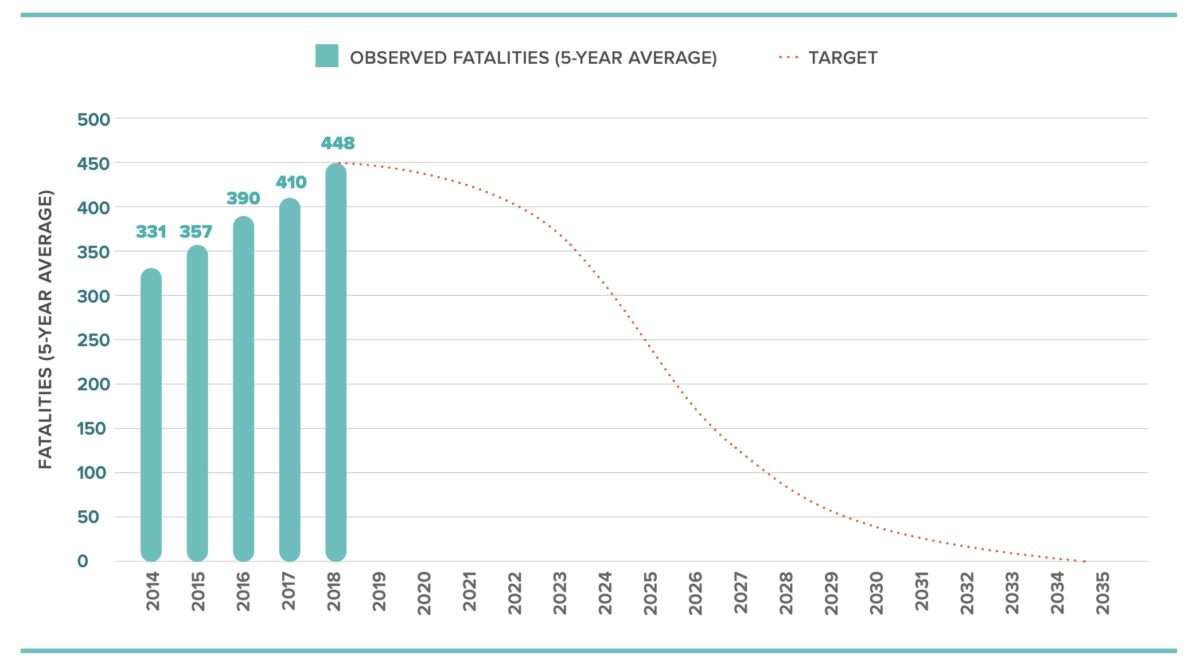

At their meeting last month the Oregon Transportation Commission adopted the Transportation Safety Action Plan, a 148-page road map for how the Oregon Department of Transportation will reduce traffic-related deaths and injuries. Given current trends, ODOT has their work cut out for them. So far this year, fatalities are up over 21% from 2020 and we’re on pace for another record high. ODOT has a commitment to reach zero fatal and serious injury crashes by 2035, but all the data points in the wrong direction.

For context, in 2010 there were 292 fatal crashes in Oregon. In 2019 that number jumped by a whopping 64% to 456 fatalities.

The TSAP (last updated in 2016) was an opportunity for ODOT to up their game when it comes to the mix of education and engineering it takes to change road safety outcomes.

According to Oregon Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee (OBPAC) Chair Hau Hagedorn, the plan gets many things right: It shares key statistics, notes the need to integrate transportation to public health, acknowledges the role of risky driving behaviors, and presents the reality of unbalanced outcomes when it comes to Black, indigenous and other people of color (especially those with lower incomes).

“However, we are concerned that this incremental change is not good enough,” Hagedorn said in testimony on behalf of the OBPAC to the OTC at their meeting on September 9th. “Evidenced by the continuing increase in traffic fatalities, we are failing as a state to reverse our fatal and severe injury crash trends.” Specifically, Hagedorn said many of the actions laid out in the plan lack teeth and are too vague. One area where the OBPAC wants more specifics is how state funding will change to meet stated safety goals.

Hagedorn also shared several other questions and concerns:

Advertisement

“How does this differ from previous plans and what is ODOT doing differently than in the past 10 years to make our entire transportation system safer?

Right now it takes two years to get crash data. If data are critical to decision-making, does the TSAP address how ODOT will resolve the issue of data timeliness?

How does the TSAP address specific actions to remediate the issues that make arterials so dangerous to all users, especially people who walk?

Enforcement is mentioned 221 times and equity is mentioned 86 times. If racial equity is a priority, there should be a focus on unbiased solutions rather than increased law enforcement actions that require the intervention of police officers.”

ODOT has to answer to more than concerned committee members. The TSAP includes performance targets tied to federal pursestrings. If ODOT doesn’t meet targets for specific types of fatal and injury crashes, they lose control over parts of their budget. For instance, under current federal transportation law, ODOT has to double the amount it spends on rural road safety because deaths have increased over the past two years. These federal requirements might be why the agency has moved its targets. As Willamette Week reported back in June, ODOT’s latest TSAP has increased its target of annual traffic deaths from 300 in 2017 to 444 in 2022.

For road safety activists who want to push ODOT to turn the death curve downward not upward, the TSAP is a great resource to gain a better understanding of the baseline numbers and issues.

Here are a few of the charts and data points that caught my eye (data is from 2014 – 2018)…

A daunting road ahead for ODOT (and they can add three more very tall columns after 2018):

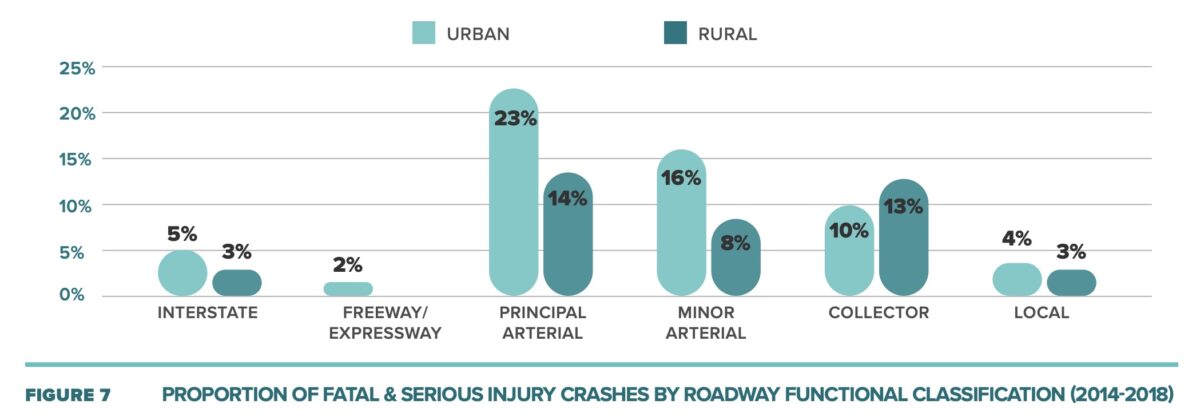

Urban arterials are the deadliest type of street in the state:

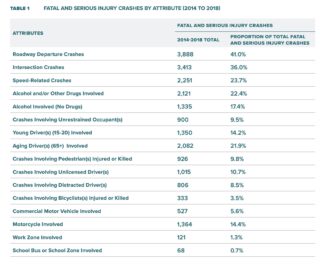

Only 3.5% of all serious injury and fatal traffic crashes involved a bicycle rider and about one in 10 involved a pedestrian:

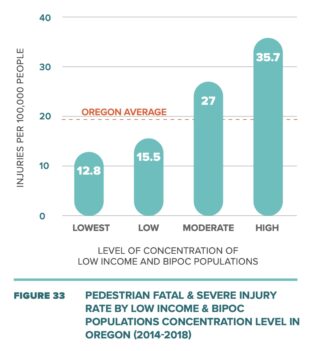

BIPOC and low-income Oregonians suffer the most injuries and deaths per vehicle mile traveled (VMT):

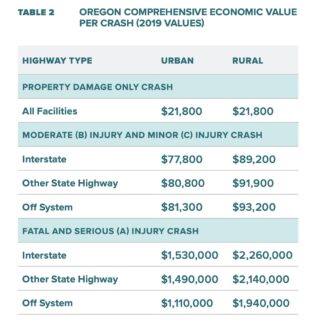

The economic cost of crashes in Oregon from 2014 – 2018 averaged $5.81 billion annually or more than $15 Billion in total:

Download the TSAP and learn more at Oregon.gov.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

We are lucky as a state to have Hau. Wish we had her on Portland’s bike committee.

Imagine if other state or city agency had such a growth in negative outcomes…many of which are under their long term control…it would be an “all hands on deck moment” with action…especially as ‘principal arterials’ are one of their principal “product lines” other than highways.

Time will tell if this new important data creates a successful pivot point for 100 years of past decisions (with little reporting) or just another call for a new report on “progress”

I served on the committee for the previous (2016) version of the plan, as the only “non-motorized” voice. Hau’s observations describe the same problems we saw then. ODOT responded to failing to meet the crash reduction targets from the 2016 plan by pushing these watered-down targets for the new plan. The solution would be to give the plan teeth, rather than let ODOT and the consultant go thru the motions every 5 years (with a new batch of well-intentioned but not empowered volunteer committee members).