(Photos: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

We bike lovers talk a lot about what we ride and how we ride, but we don’t talk enough about where we ride. And I don’t mean comparing “epic” routes in the wilderness. I’m talking about the history of the places we pedal through.

If you ride in Portland there are a few things you should know. If you’ve been here a while, you’ve likely heard some of what I’m about to share. But if you’re new to town, listen up!

And yes, this post is about racism.

There’s a lot of race-related history to uncover about our state (which was formed to exclude Black people and with a vision to be a “perfect white society”) and our city.

Here are just three bits of history to help you on your educational journey…

Portland’s Racist Planning History

That’s not me calling Portland’s planning history racist, that’s the City of Portland itself. Believe it or not, our city has a page on their website devoted to, “How historical racist land use planning contributed to racial segregation and inequity for people of color in Portland.” The meat of the site is a 2019 report that outlines in detail how planners purposely segregated Portland along racial lines.

From what types of housing was allowed to be built to covenants on deeds that intentionally excluded Black and other people of color, the way Portland is built today directly reflects a racist past. Ever notice how some streets you ride on — like Southeast Ankeny through Laurelhurst or along the bluff on North Willamette — are lined with big, single-family homes, while other streets feel much more crowded with multi-story apartments?

I highly recommend taking a few minutes to click through the links on that page, especially this interactive Google Map of racial covenants in Portland. Then plan a bike ride to some of the locations and ponder how the neighborhoods still reflect these planning decisions.

So much of our debates about density, housing, transportation and bike lanes can be tied to this planning history. Know it better and you’ll be more informed for those important discussions.

Advertisement

Vanport

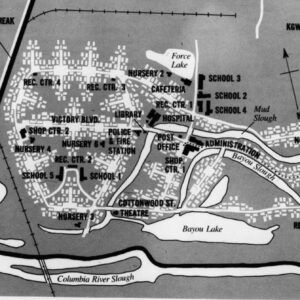

(Map of Vanport overlayed with Google satellite image)

(Map of Vanport overlayed with Google satellite image)

The path along the Columbia Slough near Portland International Raceway north of Kenton is one of the most popular places to ride in our city. It also has a view of one of the most dramatic and important events in the history of Portland.

72 years ago a flood wiped out a major city that was built where PIR now stands. Yes, the same PIR that has hosted many of your favorite bike races like MTB Short Track, the Cyclocross Crusade, Monday Night PIR, and others.

At its height in the mid 1940s, 40% of Vanport’s 40,000 residents were Black and it was the second largest city in Oregon. When the levees broke on May 30th 1948, 15 people died and 6,300 Black people were displaced.

As detailed by NPR, the aforementioned racist planning that pushed Black people away from many parts of the city, directly contributed to Vanport becoming overcrowded and led to a lack of urgency to protect it from this disaster.

If you want to ride over there and learn more about it, our friends at Pedalpalooza have put together a bike route and page with more information.

North Williams Avenue

Another popular bike route that’s steeped with racial history is North Williams Avenue.

“We have an issue of racism and of the history of this neighborhood. Until we address that history and… the cultural differences we have in terms of respect, we are not going to move very far.”

— Michelle DePass, July 2011

Before Vanport, most of Portland’s Black residents lived in the Albina district east and north of the Broadway Bridge. By 1920, 62% of Portland’s African Americans residents, and 80% of African American families with children, lived near Williams Avenue. This led to a thriving culture of music venues and other Black-owned businesses. At one point it was called the “Black Broadway” because of all the jazz clubs.

The beginning of the end of this era started in the 1960s with discriminatory “urban renewal” plans by the City of Portland. The construction of Memorial Coliseum, Interstate 5, and Emanuel Hospital decimated hundreds of homes and businesses — and the communities that once thrived because of them.

Nine years ago the Portland Bureau of Transportation wanted to build a new bike lane on Williams and this simmering history boiled over. At a meeting for the project in July 2011, longtime residents of the area objected to the bike lane project. Michelle DePass, a woman who was born in the hospital where the meeting was taking place (Legacy Emanuel) and who lived in the area around Williams Avenue all of her life, spoke up. “We have an issue of racism and of the history of this neighborhood,” she said. “Until we address that history and… the cultural differences we have in terms of respect, we are not going to move very far.”

One of the many outcomes of that controversial project was the Historic Black Williams Project, an educational effort (backed by PBOT in partnership with the community) that included a series of signs displayed along the street. If you ride up Williams today, I strongly suggest stopping to read them. They highlight cultural events, Black community leaders, and Black-owned businesses that once thrived along the street.

For links to more great educational resources about Williams Avenue, check out the links on the Black Williams Project website.

There is so much to discover! I find that having a visceral connection to a place — like when I bike through it — inspires me to do the necessary work of learning about how our past has informed the present and how to embrace them in order to create a better future.

I hope you are embracing this moment to gain more knowledge about the places we ride through, no matter what path you’re on.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

it’s weird to me to see so much support for the BLM movement from the portland bike community… i am an avid bike rider… part of the reason why i moved here 20 years ago was to take advantage of all of the outdoor activities that are available here… but as a black man… one place i’ve never felt comfortable… is in the larger biking community… whether it’s pedalpaloza events or naked bike ride or sunday parkways… whatever… i’ve never felt any of the major events in town to be the least bit inclusive nor have i felt any sense of community when i’m out riding my bike… as a result… i don’t ride much anymore… and haven’t ridden my bike much in the last 5 or 6 years…

i hope my cynicism is misguided and that this push towards more inclusiveness in the biking community in portland is really becoming a reality but based on my 20 years living here there’s a long way to go.

Hey Zuul,

I just wanted to let you know that your cynicism is not misguided. As a POC living in Portland, I have never felt welcomed by the outdoor community, but especially the biking community here. I’ve dropped out of some of my hiking groups here due to the same reasons you stopped riding your bike as much. I too hope that things are actually changing this time.

Hi zuul,

Thanks for sharing this. I’m sorry to hear you never felt comfortable or felt a sense of community at the bike events you attended or during your time riding in Portland. I too hope that is changing for the better.

One thing to keep in mind is that the “Portland bike community” isn’t really a neatly defined thing IMO. It’s no monolith. It’s made up of all types of different people. Within all these people who like and use bicycles you’ll find a wide range of beliefs and values and perspectives.

That being said, I hear you and agree with you that there remains (among a certain number of Portland bike riders) a cliquey-ness and white-male-ego-driven thing that is pretty disturbing and likely/often manifests in the unwelcomeness you felt.

I like the plaques, they are very educational but part of me feels like they are a consolation prize. Black families had their neighborhoods wiped out by the Rose Quarter, the hospital, and now gentrification. I’m working on a family housing complex on Williams, there’s a marker right there. I hope occupancy will be mostly people with a connection to the neighborhood.

Thanks for this item, I look forward to stopping and learning more about the neighborhoods I have been cycling through and shopping in for 20+ years.

In addition to the “red lining” practices and Van Port mis-management noted in this article that impacted “black” “brown” and “yellow” people, the use of the then new “urban renewal” tool funded by Federal taxes was ALSO a tool against “class”, thus impacting anyone who was not wealthy…especially the neighborhoods destroyed for the ‘mad-men era” SW development areas around the [Ira] Keller Fountain. It might be interesting to investigate the city “fathers” with names on fountains and buildings from this era and how they were involved (for better and worse) and how to move forward: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1335&context=oscdl_cityclub

With all the progressive rampaging and book burning going on lately what they should do is completely raze these neighborhoods and give them back to the displaced people to start anew.

Please take the time you spent typing this bad faith argument to read just the dust jacket of “The Case For Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates. You can probably find it at your local library.

Nope. Library is closed due to CONVID.

And yet I managed to pick up a load of books from the library just yesterday.

It seems to be kind of a soft opening, you can’t just walk up but if you go on line you can get books. They are also taking books back now.

It’s getting harder to hold out with Old Ned Ludd.

It does beg the question as to whether the Progressives living in these neighborhoods are going to vacate their homes to help with diversity.

I mean, saying you are concerned is great but are you going to move so that others can reclaim a neighborhood?

Repeating the history of an area, much of which occurred long before any of the current residents lived there is going to accomplish what?

It’s far easier to just stick a BLM sign in your yard and head down to New Seasons for some kale and kombucha.

The issue now is more economics. Most POC are just priced out of these gentrifying neighborhoods. Take the Albina or MLK areas, you’re not going to reverse the trends unless POC have the same economic powers, which is a whole other systemic problem.

I completely agree with you on that. I understand the opinions that past offenses need to be atoned for, but in my mind the most fair and attainable things we can do is ensure equity and opportunity moving forward. Some wrongs can’t be fixed.

Part of that has to be ensuring it is easier to be upwardly mobile. We’ve been working at that for decades, but so far haven’t been as successful as we need to be. I don’t know what the answer is. More money? Better programs?

I think part of the solution has to be better economic integration, and, sadly, we’ve been losing that, both in Portland and nationally, for decades. Once gone, it’s awfully hard to get back.

Let’s not forget the doomed Mount Hood Freeway and Prescott Freeway Projects et al from Robert Moses, which would have been ploughed deliberately through predominantly at the time black neighborhoods.

The Mount Hood Freeway was intended to roughly replace Clinton St, which was, as I understand it, not a predominantly black neighborhood. Generally speaking, Portland’s freeway system cut through white areas, though I really shouldn’t be spoiling the narrative.

Were they black neighborhoods? Don’t know for sure but I assumed it was white middle class neighborhoods which is why there was the political clout to stop the freeway from being built.

The Mount Hood Freeway would have been built through a poor dilapidated inner city neighborhood. It had no clout.

Another example,right through the heart of NE, and not that long ago (the 70s I believe) was the reconstruction of NE MLK, Jr. Blvd. (a state highway). It added medians which blocked east/west travel across MLK, and removed on-street parking. Businesses on MLK were already having some difficulties, and this project wiped them out. The purpose of the improvements was to improve commuting for people driving between the central city and Vancouver,at the expense of people–largely minority–living in NE.

It wasn’t just anti-black and anti-Asian, but really anti-anything-not-middle-class-WASP.

The South Auditorium Blocks were raised because it was a “notorious blighted neighborhood full of Jews, Italians, mixed races and hippies” according to my PSU planning professors. The Lloyd District was Slavic before they raised it.

Another neighborhood area with racist restrictions was the Ascot Zoning areas in the Russell and Wilkes neighborhoods, but that is East Portland so of course the Portland planning department would ignore it.

And of course the city still engages in this sort of crap in East Portland, Cully, and Brentwood-Darlington, tolerating housing discrimination and deliberately engaging in community neglect, to a certain extent in SW too.

Check out the Vancouver Junteenth Protest march going back and forth across the I-5 Interstate Bridge…for the next 15 minutes …traffic cams…

https://www.wsdot.com/traffic/vancouver/NorthPortland/default.aspx?cam=1267

Excellent statement. Though I don’t live in Portland (yet) I believe your sentiments strike at the heart of inclusivity and the absolute need for equity in city planning and reconciliation. If future plans do not take into account the injustices of yesteryear we are doomed to repeat their mistakes.

Speaking of racist planning in N/NE, the Albina Community Plan, which was quite recent (1990s) and had many good aspects, had some poor ones too. A main goal was to increase residential densities. But wealthier, whiter neighborhoods (Irvington, etc.) fought against increased density. In response, the project rezoned much of NE MLK to RH (high-density residential). Much of MLK property was blighted at the time, wiped out by the 70s median project that turned MLK into almost exclusively a through highway at the expense of its ability to function as a community main street. Quite a bit of MLK land at the time was minority owned.

With the rezoning, small businesses could not expand without building residential space, new commercial space could not be built, and even small residential projects could not be built due to not meeting minimum unit densities. There was a limited market for residential space on MLK, and projects meeting minimum densities could not be financed. For several years, the bulk of new residential space that eventually was built was at the south end, which was zoned EX vs. RH, and allowed more commercial space to be included and less residential. Eventually MLK developed, and the City very recently has taken steps to allow increased density in the wealthier neighborhoods that successfully fought it in the 1990s.

My takeaway is different. I see upzoning leading to displacement, especially where existing structures are less expensive. In most cases, the new development is far more expensive than what it replaces, and in the case of Albina, was targeted at a completely different demographic then the people already in the neighborhood.

Sure, blame Irvington, but the real cause was economics.

Yes, there are reasons why Irvington didn’t want upzoning, and yes, new development is more expensive than what it replaces. And people in single-family residential areas generally do not want developers to be able to come in and replace houses next to them with multi-unit projects. And Irvingon was wealthy enough to keep upzoning out.

But the zoning that minority-heavy property owners on MLK got was far from ideal for them and the businesses on those properties. Literally acres of businesses because “nonconforming” under the zoning code, with the problems that entails.

But they did not have the political clout to protect their interests the way the wealthier residential areas within the Albina Plan area did.

My view is that all neighborhoods should have a voice in how their zoning is structured; community leaders and members generally know what will serve them best more than the planners at City Hall do. That said, I suspect that many local owners did well from the rezoning, and may well have supported it (somebody clearly made a lot of money).

As usual, it’s lower income renters that get screwed when we upzone.

Of course people should have a voice. And, yes community leaders and members generally know what will serve them best. And yes, many local owners did well from the rezoning, and yes, many supported it, and some did make a lot of money.

That’s all at the heart of my point. It was generally wealthier people in wealthier, whiter neigbhorhoods who did well, at the expense of people in poorer, less white areas. Those in wealthier neigbhorhoods knew what would work best for them, and got it. Those in poorer areas also knew what would work best for them, and did not get it.

I don’t see the “at the expense of” part, but I do see that Irvington residents are likely better able to advocate for what they want than some other areas.

If Albina did not get the planning it wanted, and Irvington did, it was because the Planning Bureau does not generally give people a voice unless they demand it, and some are better at making noise than others.

If we instead approached planning by starting from the premise that the community should be driving the process (as we used to do with our “neighborhood plans”), then that would reduce the disparity between those who are effective at advocating and those who aren’t.

The “at the expense of” part was the rezoning of much of MLK to RH (High Density Residential). Residential neighborhoods in the Albina Plan fought against it (except Eliot). The poorer parts of MLK (north of Stanton) got it. Planning staff told me it was a compromise. They had to show zoning that created the potential of a certain number of new residential units, but they also readily admitted that MLK did not have the conditions to support RH development for many years. Also, there was virtually no residential on MLK in the areas rezoned to RH, but there were many businesses. RH was horrible zoning for them, because of its limitations on commercial development and its requirements for minimum residential densities.

So single-family residential neighborhoods preserved their single-familyness at the expense of businesses and property owners on MLK. They wanted commercial or EX zoning but did not get it because those zones would not allow Planning to get the higher potential residential densities for the Albina Plan area that RH would give.

Do you have any idea why planning staff “had to show” anything? The way you phrase it suggests there was a higher political objective in mind, one that might not have been in the best interests of Irvington or Albina.

Pitting one neighborhood against another is an awful way to do planning.

I don’t remember hearing where the goal came from. City Council? Internal Planning Bureau goals for the plan? PDC? I’d guess it was a combination of those entities creating a goal, perhaps driven by a need for Portland to show certain statistics to the State in regard to State land use goals or requirements, maybe related to the Urban Growth Boundary. I’m guessing.

I agree, pitting one neighborhood against another was bad.

PDC was also heavily involved in the plan, to its detriment as far as serving the needs of the neighborhoods, in my opinion. PDC’s problems with race and equity in N/NE Ptld could be a subject in itself.

Or even really big single family houses.

Speaking of the 1992 Albina: https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/handle/1794/6186

Thanks. That’s a useful resource I didn’t know about. Looks like 3 people don’t like it for some reason–odd.

It is a very useful resource! And 6 people voted you down for saying so lol ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

EX zoning is about as flexible a type of zoning as the Portland code allows – you can pretty much do anything. It was put in to encourage minority property owners more flexibility and to increase their property values, but it backfired over time for the reasons qqq & hk have cited. And as usual PBOT and Planning/Zoning never bothered to work with one another to match the zoning with transportation improvements (or with the reverse, to make the street match the zoning). The story of any poorly-planned area.

Good point about PBOT and Planning/Zoning not working together (although on MLK it was mainly ODOT). Zoning was changed to require more pedestrian-focused development (buildings built up to the sidewalk on MLK, no parking in front of buildings, etc. Property owners said, “Fine, but give us some pedestrians.” ODOT and PBOT said (with their actions), “No, MLK is for through traffic. We can’t give you pedestrian-friendly sidewalks, on-street parking as a buffer, or regular east/west crossings on MLK”. It was a problem for years after the zoning changed. A lot of ground floors of new projects on MLK ended up being laundry rooms and empty spaces with shades on the windows,versus the retail the zoning envisioned.

“That no part of said land shall be used or occupied by any Italians, Greeks, Hindus, Armenians or Indians, except that persons of said races my be employed thereon as servants.”

This feels peculiarly and specific, Mock’s Crest.

I can’t believe they left Turks out of that.