(Photos: Aaron Brown)

Welcome to the latest dispatch from our Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting Special Correspondent Aaron Brown, who’s in D.C. covering this event thanks to a funding partnership with the Transportation Research and Education Center at Portland State University (TREC at PSU). See past coverage here.

New Modes, New Research, New Challenges, New Opportunities

As TRB gears up to celebrate its centennial (a detail that conference organizers are eager to mention as many times as possible), it’s hard not to pick up the infectious enthusiasm and energy surrounding the exciting new fields of academic research and inquiry. As recently as a decade or two ago, academic inquiry on bicycles as transportation options were limited to a handful of specific universities across the country. Now, virtually every up-and-coming transportation planning student is well-versed (and frequently seeking a career in) active transportation, and the role it plays in designing communities.

TREC at PSU at TRB

In some ways, the bicycle and pedestrian advocates are being usurped (if not in size, then certainly in sexy PR and attention) by the significant boom in new forms of urban micromobility (and a fastidiously curious army of graduate students interested in studying their implementation). Representatives from all the major e-scooter companies are here, and numerous studies are focused on how scooters, bike share systems (dockless or otherwise), and e-bikes (sharable or otherwise) are exploding in popularity in small, but growing niche communities. The studies undertaken by these modes – who rides them, in what conditions, at what costs, at what benefits, for what purposes – are being rolled out at a pace only limited by the rate at which they are rolled out to the public. I saw research today showing how e-bikes in a bikeshare fleet in Utah were used, how bike trailers in German cities were ideal for cargo delivery, and how scooters were solving “last-mile” problems of connecting people to transit stations in low-density suburban sprawl.

The timing is fortuitous, considering PBOT rolled out their statistical findings from the scooter pilot yesterday. The new innovations in micromobility are going to provide a whirlwind of options for people to easily travel 1-2 miles, if municipal governance is generous enough with the road space. As Portland and its suburbs continue to densify (which seems likely, with the slate of YIMBY housing legislation on deck in Salem and Portland’s Residential Infill Project in line), all of the research is suggesting the new technology represents a widespread democratization of the 1-2 mile trip. Making it easier for larger swaths of the public to feel comfortable and invited to not drive for a short trip – dropping off a library book, getting to the transit center, picking up groceries – is only going to grow the latent desire for walkable, dense communities that are, conveniently, also perfect for bicycling.

In short: please, please BikePortland readers: let’s welcome back the scooters with open arms. Make fun of them all you want; but every person on a scooter is a potential partner in our rabble-rousing for a Portland with less motordom and more options for low-carbon, healthy communities.

Data (But for Who?)

There’s another major trend underway that has spurred a blossoming of new transportation research. Every Biketown ride, every Lyft/Uber, every e-scooter is collecting an enormous amount of data. The crew of engineers and urban planners who attend TRB are finding all sorts of way to put this mountain of numbers to use – mapping them, modelling them, running regression analyses, finding correlations and so on. Enormous datasets like these are catnip for the planners and researchers trained in a pedagogy that heavily prioritizes quantitative analysis.

The University of Oregon’s Anne Brown (no familial relation, although full disclosure, we had classes together in college) conducted award-winning research on Lyft’s travel data. She was granted access to a data set of Lyft travel patterns in Los Angeles, and was able to determine all sorts of interesting facts about the role that Lyft was playing in filling mobility gaps in automobile-oriented Los Angeles (check out her website to learn more about her findings).

Advertisement

The tricky problem, though, is that all of these ride-hailing services are notoriously fickle about sharing their information. This came up repeatedly in sessions today and yesterday – urban planners and researchers politely agreed that autonomous vehicles have the capacity to positively reshape american cities, but the fiercely guarded proprietary information held by these TNCs obstruct the ability for policymakers to appropriately plan for their arrival.

There are privacy concerns about this sort of data that need to be addressed, and there’s a case to be made that Lyft and Uber make their money on the closely guarded secrets hidden inside the data and therefore the government shouldn’t be prying into the numbers. But with the “AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES ARE COMING TO RESHAPE OUR CITIES” boosterism breathlessly championed and upheld by significant venture capital funding, it seems abundantly clear from the presentations I’ve seen today that the dearth of publicly available data on ride-sharing represents a challenge towards ensuring public sector entities can defend the public’s right to the street from all-too-eager-to-monopolize the right-of-way.

I Am Skeptical of the Hyperloop

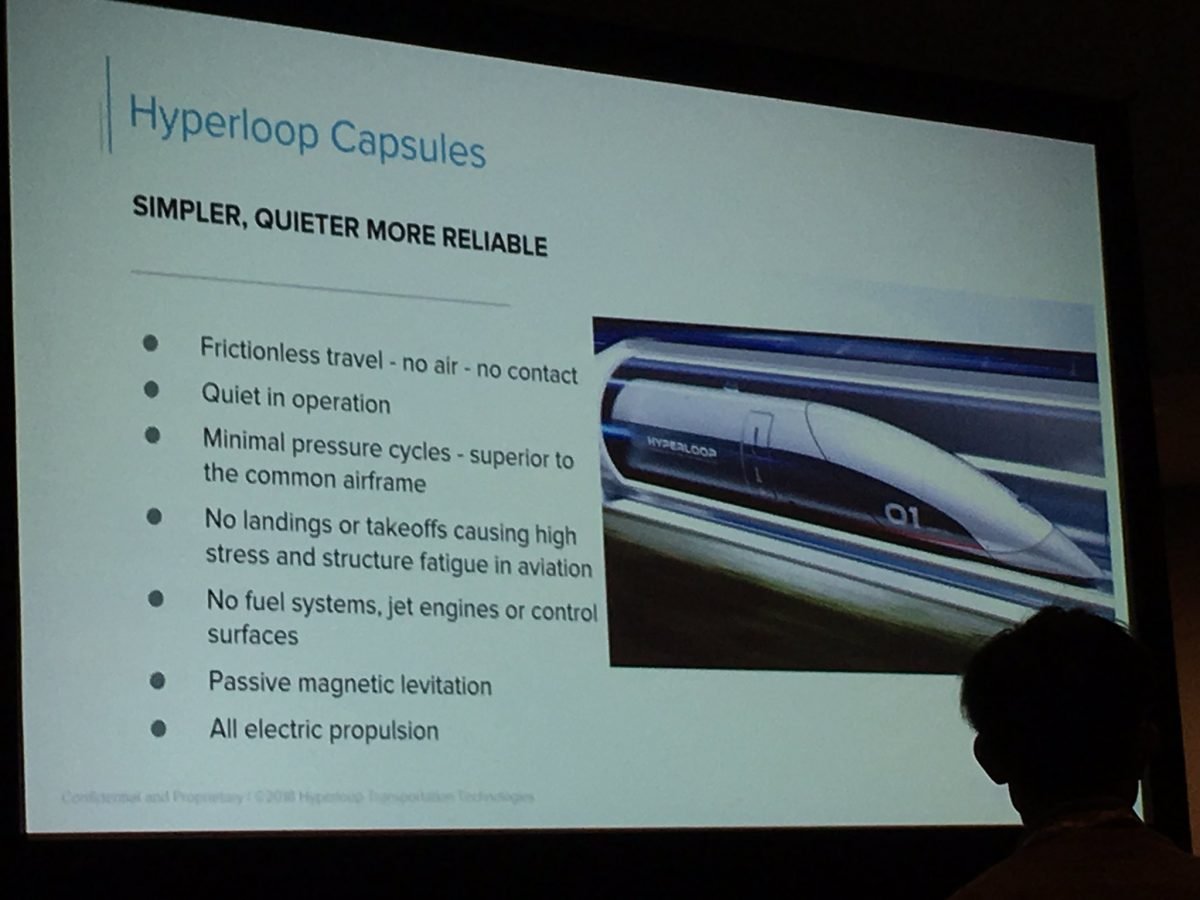

In the interest of bemused self-flagellation, I stepped in to the second half of a presentation titled, “The Feasibility of Hyperloop Travel in North American Corridors”. To my surprise, the room was packed, with at least 120 people intently listening to four presentations with fancy graphics and futuristic designs explaining how hyperloop systems could immediately be built to connect Chicago to various far-flung cities across the midwest in under an hour or two. I suppose it’s entirely defensible to be lured in by the promise of a Jetsons-esque vision of people shooting about the country at seven hundred miles an hour in pneumatic tubes, and I don’t begrudge anyone for sparing a moment to daydream about some radically fantastic new infrastructure plans (if I did, I’d have to hide all those fantasy transit maps I’ve drawn up over the years).

At the end of the day, however, somehow, not-insignificant amounts of money are being peddled around between various consulting firms and business leaders showing up in destitute midwestern towns and promoting completely unproven, expensive technology at a time in which we can’t even fund potholes on our existing roads.

Bicycles and trains were invented in the 19th century, and while we’ve certainly improved on them in plenty of ways, the technology itself is still readily available and evidently effective at providing meaningful, scalable investments in mobility both at a national scale and at an urban scale. Forget that the idea the federal government will somehow manage to find a way to acquire the endless miles of land necessary to build these facilities, or that doing so won’t be an endless mess of litigation – is the problem with American transportation really that one can’t get to Chicago from Cleveland in under an hour? Or is it that doing so without an automobile is horrifically inconvenient, infrequent, and delayed? That Cleveland’s municipal bus system is underfunded and de-prioritized, that traffic fatalities are depressingly concentrated in low-income neighborhoods of each of these communities? What problems are we actually trying to solve, here, and what problems are only going to be exacerbated by building a gajillion dollar pneumatic tube? Whose rapid speed and movement (let alone safety) are we prioritizing, and whose are stuck waiting for some curb cuts and crosswalks?

OK. That’s all I can muster. Off to a gathering of our friends from TREC at PSU! Stay tuned.

Views expressed by the author are his own and do not reflect those of TREC at PSU.

— Aaron Brown, @ambrown on Twitter.

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I’ll have to check if you’ve posted it already, but has there been discussion of Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V) and Vehicle-to-people/infrastructure (V2X) technologies? This is the more impactful (to peds & cyclists) development area, and a key differentiation in the future of AVs co-existing alongside non-enabled entities.

I posted a comment on LinkedIn just yesterday on a video that Wind River posted showing their mobile AV lab and use cases. Lab comes up behind stopped car on multi-lane road and stops. Lab then shows automated passing of stopped car in next lane, but how is Lab to be certain the stopped car isn’t waiting for a pedestrian to cross in an unmarked crosswalk? Even human drivers don’t seem to understand such things occur, and peds are often hit because the compliant (stopped) car obscures the view of them.

On theory, V2V could solve this by the stopped car broadcasting the situation to other cars/AVs that pose a threat to this pedestrian. It’s a common real-world problem involving broader contextual awareness that simple LIDAR and video sensors can’t prevent.

Also, will we need to tether ourselves to smartphones to survive walking or riding a bike on the streets of future “smart cities”? (And what if our battery dies?).

I share all of your skepticism about hyperloop. On the technical feasibility side, I simply find it implausible that this could scale to large distances and provide an efficient and reliable means of transport. Simply put, it’s too complex to not have problems. Maintaining near vacuum over huge distances of large tubes is just an incredible engineering challenge.

But I’ll add one other thing to the “what problem is this solving” question you posed. What does this do that a maglev train can’t already? Faster, sure. Lower energy use, maybe. But, coupled with capacity, I think those are both marginal gains at incredible increases in cost and–probably–reliability. And given that this country can’t marshal the interest or resources to build a maglev that would also shuttle people intercity at fantastic speeds, doing so with hyperloop is, by my estimation, nothing but a pipe dream (pun fully intended).

“And given that this country can’t marshal the interest or resources to build a maglev that would also shuttle people intercity at fantastic speeds …”

Heck, this country can’t marshal the interest and resources to build a high-speed train on regular metal rails, outside of a couple of corridors. Even in the Pacific NW where at least the Cascades corridor is well served frequency-wise, I-5 (whether driving an automobile or riding a BoltBus) is still faster between Portland and Seattle than Amtrak. Real high-speed rail could bring the trip down to under 2 hours (making it significantly faster than flying, when you take into account the time wasted getting through airports) but isn’t even on the table. Slower than maglev, yes, but vastly cheaper and still not happening in the foreseeable future.

Speaking of Chicago, we’re only just now on the verge of getting a second daily Amtrak run to Chicago from Minneapolis, where I live. High-speed rail service to our second and third largest metro areas (Duluth and Rochester) is still in the planning stages, many years from actually happening. Part of the holdup is that the Rochester line would continue to Chicago across Wisconsin, and the governor of THAT state notoriously held up planning on this line for years – but with new leadership, WI might start get moving on this again.

In any event, I agree that hyperloop is at best a monorail vision that gives a hopeful glimpse of some distant future but probably won’t work for very many people, and at worst a distraction from what really needs to be happening. Which, in the case of intercity travel, is simply expanding and improving our bus and steel-rail service.

Key engineering problems for Hyperloop:

1. Cost of tunneling. Musk’s demonstration project hsn’t proven that they can reduce the cost of tunneling. The majority of the track would need to be underground due to our topography.

2. The physics of vacuums. A vacuum tube that long would require significant structure, due to the forces involved. Also, if a seal breaks or the tube is punctured, the shock wave would kill everyone inside.

3. No egress options. Plans can land, trains can stop and unload passengers. How do you evacuate a hyperloop tube?

4. Thermal expansion. A tube that long would stretch by hundreds of feet in the summer heat. You would need some sort of gaskets between sections, which still have to hold a vacuum and deal with the forces involved.

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Hyperloop

If those problems turn out to be insurmountable, I suspect they will not be surmounted.

I suspect the cost of tunneling alone will kill widespread adoption of hyperloops. Large scale tunneling efforts (Boston’s Big Dig, Seattle’s almost-completed SR99 tunnel, Portland’s own West Hills MAX tunnel) always seem to run into large scale delays and cost overruns. A 500 mile long vacuum tunnel through one of the nation’s most active seismic areas? Not in my kids’ lifetime.

Meanwhile, welded steel rails currently support commercial rail in multiple countries with speeds in excess of 200 mph. At least for regional trips up to a few hundred miles, I can’t think of a reason anyone needs to go faster than that. Not that a trans-California steel rail route wouldn’t need some tunnels too, but hyperloop would be orders of magnitude more expensive.

Tunnels are actually safer during an earthquake; much the same way that a submarine would barely notice a stormy sea, while a small boat would be violently capsized.

>>> I suppose it’s entirely defensible to be lured in by the promise of a Jetsons-esque vision of people shooting about the country at seven hundred miles an hour in pneumatic tubes <<>> is the problem with American transportation really that one can’t get to Chicago from Cleveland in under an hour <<<

If there were only one problem with American transportation, this might not be it, but there is room for more than one problem. Finding a less polluting alternative to air travel has got to be on the list somewhere. Maybe it would be used primarily to transport freight, or for some other purpose we haven't yet figured out.

It is up to proponents of hyperloop to prove their case. They will do this by demonstrating they can make it work, and that it is better than alternatives like trains. If they fail, it's no skin off my nose. They're spending their own money, and even in failing, we might learn something.

I only wish more people had the gumption and wherewithal to take on the big problems.

Let’s try that again:

>>> I suppose it’s entirely defensible to be lured in by the promise of a Jetsons-esque vision of people shooting about the country at seven hundred miles an hour in pneumatic tubes <<<

It’s only as defensible as the promise of a Jetsons-esque vision of people shooting about the country at seven hundred miles an hour in flying tubes

>>> is the problem with American transportation really that one can’t get to Chicago from Cleveland in under an hour <<<

If there were only one problem with American transportation, this might not be it, but there is room for more than one problem. Finding a less polluting alternative to air travel has got to be on the list somewhere. Maybe it would be used primarily to transport freight, or for some other purpose we haven't yet figured out.

It is up to proponents of hyperloop to prove their case. They will do this by demonstrating they can make it work, and that it is better than alternatives like trains. If they fail, it's no skin off my nose. They're spending their own money, and even in failing, we might learn something.

I only wish more people had the gumption and wherewithal to take on the big problems.

We have an alternative to air travel that works all over the world: electrically powered trains on steel tracks.

Hyperloop is already wasting public money. The city of Cleveland is spending $1.2mil to study it, and Chicago is about to jump head-first into a project connecting downtown and O’Hare. It is supposed to be privately-funded, but what happens when they get it 30% built and run out of money?

Oh boy, I wish an electric train could get me from Portland to NYC in less than a day next week – maybe I wouldn’t have to wait two hours in a TSA line to take my shoes off! Seriously, I took Amtrak (diesel, sorry) from Boston to Albany (NY) and worked quite comfortably and productively for the seven+ hours it took.

Given my experience with passenger trains in the US, there’s no way I could reliably schedule meetings with my stakeholders and expect to show up on time. I assume when you say “all over the world”… you mean the rest of the world.

Boston to Albany in a car takes 3 hours, for those who don’t want to make a day of it. It’s also a fair bit cheaper, even if you rent a car; doubly so if you travel with a passenger or two.

I’ll also note that scheduled train service from Boston to Albany is closer to 4 hours, so your reported 7 hour travel time, which seems par for the course for Amtrak, is part of the problem with train travel in America. You have no idea when you’ll arrive.

Bingo! My work is in Schenectady; my family in Boston. I often use Greyhound to visit over weekends before jetting (again diesel, sorry) to other east coast or European work locations. My sister volunteered to drive me that day, and if you’d ever spent three hours in a car with my sister, you’ll know why I raced to the Amtrak web site immediately!

Was quite a cozy ride with scenery, but yeah, we spent a lot of time sidetracked. When I lived in Albany, OR, I’d take Amtrak to Seattle and learned to take a later train, which would pass the earlier train on a regular basis.

Speaking of electric trains, lets ask Jerry Brown how the electrification of Caltrain in the Bay Area is going (politically)…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDOI0cq6GZM

I knew it before I clicked on it :). Cue Nelson

Ha ha!

>>> Bicycles and trains were invented in the 19th century <<<

The hyperloop concept has been around since the 18th century.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vactrain

Not to get too far off on this tangent, but there is a vast void between “a concept” and “invented,” as being used here. While some dude drew up the idea of a “vactrain” in 1799, none was ever built. The only thing remotely similar that was ever put into practice used a pressure-differential tube to propel a traditional train car (i.e., the train itself was not in the tube). That’s a vast difference from the hyperloop idea, which again was just a sketch until now.

“…every person on a scooter is a potential partner in our rabble-rousing for a Portland with less motordom and more options for low-carbon, healthy communities.”

We can parse motor size, fuel source, etc., but technically, every person on an (e-)scooter is a disciple of motordom.

Low carbon is good; high lithium is terrible.

We should not lose sight of the fact that people on skate boards, roller skates, feet, and bikes manage to thread this needle. No tradeoffs, IPOs, leveraged buyouts, smart phones, public-private partnerships, or lithium required.

Is a scooter really “high lithium”? I mean, compared to the (originally) 24 kWh and now 100 kWh or larger battery packs contained in electric automobiles, their batteries are pretty small – on the order of magnitude of laptop batteries. Are you out campaigning for laptop users to switch to desktops too, so that we can reduce global lithium demand?

“Is a scooter really ‘high lithium’?”

One scooter isn’t, obviously, but several thousand, thrown out after four months, makes, what, 6,000/yr… just for Portland …starts to add up.

“I mean, compared to the (originally) 24 kWh and now 100 kWh or larger battery packs contained in electric automobiles, their batteries are pretty small – on the order of magnitude of laptop batteries.”

This is where product life and the total number come into play. Now that we know something about the dastardly, toxic, human and ecological toll from extracting and processing lithium, never mind it’s finished, the question shouldn’t in my mind be how we in the overdeveloped world can justify this or that application, but how we can back out of this lose-lose situation.

“Are you out campaigning for laptop users to switch to desktops too, so that we can reduce global lithium demand?”

Another false dichotomy. Why not try to imagine a solution with fewer externalities rather than this sort of gotcha retort?

#whataboutism

It’s not whataboutism, it’s about perspective and not looking at lithium use binarily.

What about titanium bikes? Disciples of motordom or threading the needle? Heck, steel and aluminum mining aren’t pretty either. My point, of course, is that drawing a line at lithium is a rather arbitrary exercise. Carbon has impacts. Mining has impacts. Manufacturing has impacts. While I won’t argue that lithium mining is a good thing, I just can’t see how a certain degree of externalities in mining translates well to motordom. While not by any means suggesting we ignore environmental impacts, I’d suggest measuring “motordom” is probably better done by looking at personal harm (in the injury sense) and impacts on local resources (e.g., land use and development).

“drawing a line at lithium is a rather arbitrary exercise.”

Perhaps, or maybe not. A very short-lived (throwaway) product that relies on a lithium battery, is pretty low on the scale of responsible material use. Steel could easily be argued to be an order of magnitude less burdensome. My steel bike I bought thirty two years ago is still going strong.

But, your larger point, that we are running out of most things, is valid, and we would do well to take that seriously.

We are not running out of most things.

Right.

https://www.amazon.com/Race-Whats-Left-Scramble-Resources/dp/1250023971

We’re actually eerily on track for what the Meadows and Randers predicted in 1972’s Limits to Growth.

“As Portland and its suburbs continue to densify (which seems likely, with the slate of YIMBY housing legislation on deck in Salem and Portland’s Residential Infill Project in line), ”

Portland’s R1 zone already allows triplexes and 4-plexes and with far fewer zoning disincentives/restrictions than the residential infill project but development of triplexes and 4-plexes has been virtually non-existent on these lots.

Why would the anti-renter residential infill project change this long-term dynamic? (The Residential Infill Project is riddled with provisions and restrictions that discourage rental unit development.)

A very very small portion of the city is zoned as R1. Even along our high-capacity transit corridors, most of the housing is R2.5. Nearly all of the remaining housing areas are R5. Are you just ignoring all of these properties?

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=2ahUKEwiFgqbio_PfAhWhMX0KHREQAlsQFjABegQICBAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.portlandoregon.gov%2Fbps%2Farticle%2F59265&usg=AOvVaw05n7JyoGnpFUyBNBqvF8_7

Those properties are precisely my point.

The current RIP proposal will do little to change the mix of housing types in those zones because it disincentivizes productions of the “plexes” it purports to enable while incentivizing production of owned single family homes.

To reiterate: the R1 zone represents a natural experiment of what will likely happen when R2.5, R5, and R7 are re-zoned under the current RIP proposal. Despite the fact that R1 allows for triplexes and 4-plexes almost none have been built. Moreover, unlike the RIP proposal, R1 zoning does not restrict 4-plex units to an insulting ~700 sq ft and does not allow for lot subdivisions which encourage single family housing. Essentially we have a zone that is far more permissive to small multifamily rental housing than the RIP proposal and this zone has utterly failed to produce significant amounts of additional rental housing.

Instead of ridiculous half-measures we need upzoning that actually encourages affordable rental unit production, not more unaffordable single family homes.

What is the Residential Infill Project? Somehow I missed this.

“Every person on a scooter is a potential partner in our rabble-rousing for a Portland with less motordom and more options for low-carbon, healthy communities.”

Exactly the point I made on the scooter thread. We expand the constituency for non-car transport with these scooter programs.

When you expose people who drive to what it’s like to navigate around and near cars, you likely yield more conscientious drivers when they get back behind the wheel, too.

Now that… is the first plausible argument in favor of these devices I’ve read here in these pages. Thank you.

Given that a substantial fraction of scooter users are in the “never bike” demographic you may also create a new pool of people interested in giving cycling for transportation a try.

Possibly. I guess I don’t know enough to speculate whether that is likely or plausible. Anyone know of an attempt to gauge this possibility, this imagined effect?

Additional problems with Hyperloop: The vacuum tubes are supposed to be at a pressure equivalent of around 150,000 feet altitude. This is to lessen air resistance and because the speed of sound is faster than an altitude of about 60-70,000 feet. Unprotected at about 60-68,000 feet (I forget the precise number) your blood will basically boil, which is why U-2 and SR-71 pilots wear full pressure suits. With others stating that a rapid return to normal pressure is not safe, and a sudden depressurization is not safe, how do you make the current concept safe?

Possibly the concept would work at a vacuum equal to about 60,000 feet. The air resistance would be higher, and the the top speed lowed due to the speed of sound being slower, but the problems are economics rather than fundamental safety problems. More cooling and more propulsion energy would be needed due to the higher air resistance.

However, I suspect the energy (cooling, propulsion, and vacuum systems), vacuum system maintenance, and construction costs would make the hyperloop way too expensive to be a viable form of transportation.

The challenges are indeed formidable. It will be interesting to see how they are addressed.