(Photos: Catie Gould)

“How can bicycle advocacy be more inclusive?” and “How can we make streets safer without causing gentrification?” were central questions that Portlanders asked at a standing room only event on Thursday night.

“Transportation safety [advocacy] is tied up in other ways we decide who’s important and who’s not important.”

— Dr. Adonia Lugo

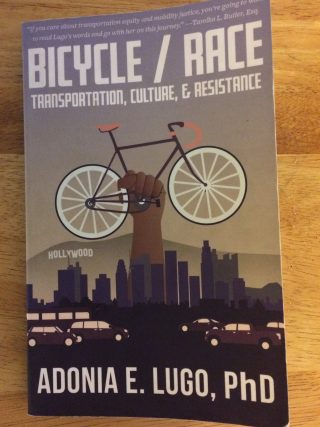

Adonia Lugo, a former bicycle activist with a PhD in anthropology, spoke at a packed event last night. Her recently published book, Bicycle / Race: Transportation, Culture, and Resistance (2018, Microcosm Publishing), follows the trajectory of her cycling experience — from becoming a bike commuter in Portland, to her work establishing the CicLAvia open streets event in Los Angeles, to her struggle to integrate equity during her tenure at the League of American Bicyclists in Washington D.C.

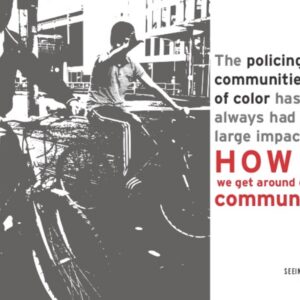

Lugo’s book looks at the way a focus on the traditional bike advocacy focus on infrastructure doesn’t go far enough to dismantle the injustices on our streets. Lugo explained that when advocates talk about street safety as a goal it usually only focuses on vehicular interactions, but “mobility justice” looks at the broader picture of how our bodies are not just vulnerable to cars, but some bodies are also vulnerable to racial profiling, sexual harassment, or even not having the right documents.

After leaving Portland and returning to Southern California where she grew up, Lugo noticed the people who biked were people of color who didn’t seem to have access to a car. And something clicked: “People who were dealing with so many kinds of oppression and so many ways of being held back and denied access to the American dream also weren’t going to be safe as they travelled because they couldn’t afford to drive. For me, looking at transportation and transportation safety is tied up in other ways we decide who’s important and who’s not important.”

Lugo sees bicycling as a powerful decolonizing force, a way for people to feel powerful and mobile in their public spaces, and a way to reduce their tie into materialism and oil consumption. But a lot of advocates don’t see biking in the same way. “For a lot of people who get involved in bicycling or bike advocacy, their lives are maybe not that bad structurally, maybe they have access to economic security, maybe they grew up in a house their family owned, maybe they got to go to college, maybe they have a six-figure job and they love bicycling, and riding a bike is that one time of the day that they don’t feel safe or they feel like something is wrong with the system.”

Advertisement

The issue with infrastructure-only advocacy done mostly by people of privilege, Lugo says, is that when we define the problem of safety so narrowly, we often come up with a narrow set of solutions.

During her presentation, Lugo walked us through how the urban planning field is fraught with inequality. This field has decided to take examples of roads in Northern Europe that we like, and change roads in U.S. cities to be similar. In doing that, a whole industry was built that perpetuates the problems of who gets to decide which urban design projects are failures, and which ones are still worth pursuing. The planning process requires access and agreement to public officials and agencies, and planning and design firms who benefit from our public tax dollars. When those people get paid for months to manage those projects before community engagement even begins it reinforces the unequal power dynamic.

What would a better public engagement process look like? There is no easy checklist to follow and Lugo wouldn’t want to create one. Often well-meaning advocates push for projects on behalf of these communities, without people from the community itself defining the problem of what needs to be solved. Engagement needs to happen much earlier — before proposals have momentum behind them — to be authentic. Funding also needs to be more flexible to accommodate types of “human infrastructure” that the community needs; such as neighborhood bike shops and programming for residents. Lugo believe we need to invest in experimental processes for a different kind of community engagement.

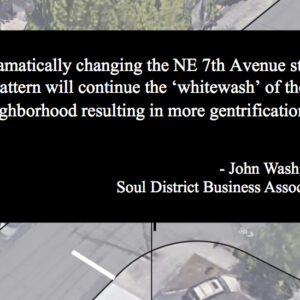

Several people in the audience asked about the controversy around North Williams, and the current tension around the Lloyd to Woodlawn greenway project. There were no easy answers about what the path forward should be, but Lugo recommended some books that dive deeper into the topic of bike lanes and gentrification such as Bike Lanes are White Lanes (2016, University of Nebraska Press) by Melody Hoffman and Bicycle Justice and Urban Transformation: Biking for All? (2016, Routledge), which Lugo also co-authored.

For Lugo, the fight for transportation justice isn’t all about a war on cars. America’s history of segregation and racism should be the main story, not just a footnote.

— Catie Gould, @Citizen_Cate on Twitter

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

All of these books sound cool as heck! Thanks for the spotlight on Dr. Lugo and her work.

Yeah… thanks for covering this!

A public policy advocacy organization can only be effective if it is narrowly focused on one specific issue. The reason for that is that in order to be successful an interest group has to present one unified front, and that can only be achieved if the membership is wholly united around one central public policy goal. Even if only a small percentage of the members disagree with a policy position that an advocacy organization has taken, then its efficacy starts to diminish rapidly. If Bike Portland wishes to be successful as an advocate for improved biking conditions in the Portland area, then it needs to focus on that mission and not become a general Huffington Post of Portland opinion outlet. For instance, we may suspect that NRA members are generally likely to favor prayer in schools, the NRA is only focused on one issue.

There are all sorts of statements in this editorial that are controversial even among people who, say, generally vote Democratic or consider themselves to be liberal. Obviously, I am not going to unpack all of them, but I will just give an example. One sentence implies that “not having the right documents,” which is an obvious code phrase for illegal immigrants, is somehow a condition that is comparable to being victimized by individuals who fail to follow the law. Last week, the Economist, a huge proponent of generally liberalized immigration policies, commented in a survey of Australia, that one of the reasons that immigration to Australia is not as controversial locally as immigration to the U.S has been is because the Australian government has secured the country’s borders. Ironically, just tonight Mark Shields, a liberal commentator, made the same point on the PBS NewsHour: while Democrats can be the party of diversity, they need to recognize that illegal immigration is illegal. So even proponents of immigration can consider illegal immigration to be problematic. If Bike Portland becomes a general website for expressing opinions on all of these issues, then its support base will splinter into dozens of little pieces. Bike Portland would do well to remain a narrowly-focused advocacy organization, and not opine on a whole range of issues that are at most tangentially related to biking in Portland.

I wouldn’t get too hung up on what is and isn’t illegal. All laws are human creations (well except for the laws of thermodynamics), and most laws are eventually overturned because they turn out to have been flawed or become untenable.

The centuries of US interference in the affairs of Central America which ruined the lives, the prospects, the future of millions of brown people should have been illegal.

Like driving and parking in the bike lane? Who is it hurting, right?

#false equivalencies are getting tiresome around here.

Power is distributed rather unevenly around these parts. People with cars, people who are white, people who are US citizens, people who are predisposed to shout ‘they’re not following the law!’ all have more; people who ride bikes, who are not white, who were born in Central America, or those who may not have papers, have rather less. Your attempt at humor, gotcha, equivalence falls flat when you take account of these asymmetries.

I agree with you. I just think you need to avoid ridiculous generalizations. It weakens the argument.

“the Economist, a huge proponent of generally liberalized immigration policies”

nonsense. the economist has always been a proponent of economic and sociopolitical darwinism.

Do you happen to read the Economist regularly? I will give you just one example of their strong pro-immigration stance: an article on March 15, 2017, published under the Free Exchange column, had the by-line that “Whatever politicians say, the world needs more immigration, not less.” And there have been dozens more pro-immigration articles just in the last twelve months.

Has the problem of illegal immigration been identified outside of “but it’s illegal”?

Isn’t that enough?

I didn’t even understand the question.

If it’s now such a high priority problem that requires the elevated response, shouldn’t it be clearly articulated what the problem is? What’s the negative created vs. what is gained? What do illegal immigrants contribute vs. what do they take away? And how much energy and money should be spent as a result? I prefer our government have a better handle on what the actual problem is before we start dropping billions. Or maybe it’s gotten a recent emphasis due to something else? Hmm…

It seems very simple to me. I love immigrants, and welcome them, and help them where I can, but people should not be in our country illegally. If we want them here, as I do, we should offer them legal status.

Do not interpret even a single word of what I wrote to be a defence of our current policies. They are a disgrace and an embarrassment. They are also very far from the topic of this blog.

HK, you’ll notice a tendency for far lefties or righties to interpret any disagreement as you being completely against everything else they believe in.

Many progressives can’t understand that a liberal can want strong borders, and many Tea Party types cannot understand that you can be critical of your country but still think it is exceptional.

I would prefer that illegal immigrants felt safer riding bikes than driving without a license.

Tangential but possibly related: you can see many California license plates in Oregon agricultural communities during harvest, partly because Californians voted to grant driver licenses without requiring citizenship. (Opponents argued that driving is a privilege that should be extended only to legal citizens whose taxes pay for the roads, whereas proponents argued that DLs don’t prevent people from illegally driving so at least the education and fees and insurance associated with licensing will help prevent some of the safety and financial issues of illegal driving).

” legal citizens whose taxes pay for the roads”

Those opponents are, I think, rather misinformed. Those who I know here in aoregon who don’t have papers pay into the system in all the ways the rest of us do (gas taxes, income taxes, property taxes, etc.) they just get less back (social security).

So we’re clear, I am summarizing here the viewpoints expressed by opponents of the measure (several years ago). For the record, this is not a summary of my understanding of public infrastructure financing.

” the NRA is only focused on one issue.”

Maybe not –

“That’s when we decided we were a ‘Liberty Education’ organization,” Vernon said at his dining room table, reflecting on the organization’s decision to give up its laser focus on Second Amendment causes and begin promoting the teaching of conservative values to children. “Membership increased significantly when we started saying, ‘Look at what’s in our textbooks,’” Vernon said.

https://undark.org/article/climate-change-science-textbooks-classrooms/

Thanks, Catie, for your excellent synopsis. Lugo’s insights and perspectives are profound and illustrate the magnitude of the challenges of we face as a country. Her suggestion of broadening our definition of safety could be transformative. At the local level, having repeatedly felt disenfranchised by the public involvement process, I couldn’t agree more about the need to engage the public earlier in transportation projects and just about any other public endeavor.

Lugo is happy to express, at length, her academic gripes, but when it comes to concrete positive suggestions, she bails out.

Why does that invalidate her message to you? Criticism is a thing. There is no compulsion that someone with a sound critique also symmetrically offer solutions.

It does not invalidate her message, per se, but I expect more from an academic. If they have put so much thought into a subject, I feel they have an obligation to offer solutions. Otherwise, they are just editorial writers or blog commenters. . We have plenty of them.

“I feel they have an obligation to offer solutions.”

I get that. And appreciate the sense that balance would be good, helpful, constructive. I’m all about solutions. But your original post seemed a bit harsh. Some people (academics?) are simply better at interrogating the problem, revealing how we got here, what went wrong. I can appreciate if some are reluctant to wade into policy, solutions.

it’s funny how you complain about “academic gripes” but are unable to list even one of them. it’s almost as if your comment has more to do with bias than genuine policy differences.

How about ‘infrastructure-only advocacy only by people of privilege’? I could find more examples, but you can do your own re-read.

And despite your claim above, that comment directly suggests a solution: more of an emphasis on infrastructure advocacy from marginalized folk.

“…weren’t going to be safe as they travelled because they couldn’t afford to drive.” -Adonia Lugo

Ugh, there it is again, that constant messaging that riding a bicycle is much more dangerous than driving. If that were the case, people who ride wouldn’t have longer life spans than those who don’t.

Some people get injured and even killed while riding bicycles, but so do people who get into motor vehicles and the rate of roadway death isn’t much different for these two modes. Also, both are quite a bit safer than walking, but we don’t often hear stories about how brave one must be to walk. (Could that be because people who are addicted to driving have to walk to and from their car?)

I’m so weary of this tired anti-advocacy that is embedded in the “scary to ride” message I could scream. The problem is, how can you get separated infrastructure built if you don’t send out this message? I would say that if the scary messaging is necessary for the type of infrastructure you want, then you’re going to have some awfully unused infrastructure, because that messaging is “driving” potential and former cyclists back into cars in droves.

Should read “weren’t going to *feel* safe…”

B,

Can you point us to sources of those comparable rates?

Although it’s a bit dated now (wow, time flies), Jeff Mapes’ “Pedaling Revolution” covers some of the studies that attempt this comparison, as well as the difficulties in measurement and cause attribution of ‘unsafe cycling’ practices (wrong-way riding, sidewalk riding, etc.).

(And I have to do this here these days – to be clear, I am not saying the examples I gave are unsafe cycling practices, I am quoting some of the factors Mapes’ found attempted to be recorded (accurately or not) in crash investigations).

I’m sure lots of the ‘old timers’ here have already read this 2009 book, but I recommend it.

The reason I asked is because I suspect the statement was (politely) hypothesis.

As a rate is a comparison between number of events and some other representation of population or use, and the denominator is almost impossible to come by for people that walk or bike, the rate for such users is therefore almost impossible to come by, so to imply they are comparable is a WAG.

http://www.pedbikeinfo.org/data/factsheet_crash.cfm

>>> Often well-meaning advocates push for projects on behalf of these communities, without people from the community itself defining the problem of what needs to be solved. <<<

Sounds to me like a call for communities to have more self determination in setting landuse and transportation policies. If so, count me in.

For every self-determined individual, there’s nine Ipad users who could care less…

Also true: “Often well-meaning advocates push against projects on behalf of these communities, without people from the community itself defining the problem of what needs to be solved.”

Some “well many meaning advocates” have a bit of a savior complex.

“Sounds to me like a call for communities to have more self determination in setting land use and transportation policies. If so, count me in.” Be careful what you ask for Hello Kitty; there are plenty of “communities” (nowadays an increasingly abstract and almost meaningless term) who feel there should be no bike lanes at all. Or even no sidewalks. These “communities” are entirely car culture oriented. So do we we bow to their wishes? Are we disrespecting those communities if we don’t follow their demands? The various real and imagined communities should have their say, but at some point listening is over. Things are going to be done or not done, and some of these communities will not get what they want. If you’re looking for a solution that makes everyone happy you’ll be waiting a very long time.

It’s a tough issue, I agree. The alternative seems to be to give communities less say in what happens to them, and I’m not sure that centralizing planning has had an overwhelmingly positive effect in most cases.

Generally, I trust people to know what’s better for them than larger, more distant bodies. You could easily come up with a dozen examples of where this isn’t true, as could I, so it’s not a perfect solution, nor would I apply it in every situation.

However it is generally where I start, and for me, the burden of proof is on those who would make decisions at a higher level to show why the outcome would be better. But, I freely admit, sometimes higher level is better.

Where was this event? Doesn’t look like Powell’s.

I wondered the same thing, gotta agree here. I know blogging isn’t journalism but I do miss Journalism 101 principals in writing nowadays. You know, “who, how, where, when and why” as a basis for an article.

Great article, but you forgot to rep the event and sponsoring organization!

Bikes for Humanity at Bingo Used books on 33rd and SE Powell Blvd

Thanks for the clarification, Dardanelles! I’m excited to see so much attention given to tough questions on Bike Portland, and that our event on Thursday inspired the conversation.

We see and respect Dr. Lugo’s forward thinking, and connect to it philosophically as an organization. The content of Bicycle/Race resonated with me, especially as our presence is on Powell, whose sidewalk sees as many cyclists as some greenways. It is precisely those cyclists who are left out of conversations regarding spending of public money on bike infrastructure, as Adonia discussed at the event. For folks who can’t afford to maintain a car, who can’t fulfill their mobility needs with TriMet, or who can’t afford to take TriMet, a bike will always be an empowering option. We are committed to refurbishing and redistributing bikes that may otherwise fall into the waste stream, and to make the financial barrier to riding a bike $0 for folks to whom that makes it exclusive.

Each year we provide 50+ earn-a-bike experiences to folks who want to ride but can’t afford the cost, 25 through our partnership with Central City Concern, and we grant dozens of bikes to Bike Safety Education graduates in Title I schools served by the Street Trust. This is not work that is done through grants or to fulfill other funding. We do it as a crucial part of our mission, funded only by the in kind donated hours and work of volunteers, used bikes and parts from the community, and profits from refurbished bikes sold in our space. Safe Routes to School BSE, community-based repair projects like ours, Bike Farm, Community Cycling Center, PSU Bike Hub, WashCo, and all the other DIY projects in the area, as well as basic safety improvements east of 205 are the future of an inclusive bike advocate culture, IMHO, and you can follow our work here http://www.b4hpdx.org/blog! Thanks again for covering this conversation!

Thanks for those elaborations.

Bikeportland commenters tend, or would appear to tend, toward the other end of the spectrum, and consequently sometimes seem to have difficulty putting themselves in the shoes of someone for whom the bike serves as a free, unfettered, point to point mode of transport, and for whom the motorized alternatives don’t really figure. I appreciate your work with that group and bringing it to our attention.

Yes to more and better community programming! Owning a bicycle that is useful for commuting in Portland is a big up front cost. While bike share could help with some trips is isn’t enough. How about a city wide bike loaner program that includes all the gear you could ever need to give riding a bike a try?

“Owning a bicycle that is useful for commuting in Portland is a big up front cost.”

Please don’t spread rumors.

This is only true if you buy everything brand new. I’m sure many do, but there is absolutely no reason to do this.

Bike, racks, fenders, lock, lights, helmet: $150-$200 if you are patient.

I totally agree. There are perfectly usable bikes on Craigslist for under $150. I bought my bike that I use regularly on Craigslist.

$150??? I got a sweet sweet Cannondale Synapse Carbon Disc Ultegra SE from a guy walking along the I-205 path for $35, 14 aspirins, and half a bottle of Pepsi. It even came with part of a cable-lock already attached to the frame.

Ah, but yours didn’t have the goodies that Kiel wants for his commute.

I had an XL Fuji Sports 12 (cranberry colored) purchased in the early 1980’s that I donated to the Community Cycling Center, thinking I was doing a good deed. (Admittedly I wrote off the donation on my taxes for ~$50 value). A few years later I saw it posted on Criag’s List and I emailed the OP; it had just been sold for ~$200. (Some capitalist apparently helping the ‘community’… I’m going to guess a small profit was made).

P.S. Coincidence… I think we get our aspirins from the same guy!

This is just standard Portlander gear lust, nothing more. You ever notice how so many people will put on their $250 ultra-lightweight mountaineering shells here when it’s cloudy out and they need to get from their Prius to the New Seasons door? Those same people also insist that it’s expensive to buy a bike with everything you “need” for commuting.

I can make fun of them because I am one too, my current commuter (former ultralight touring bike) was around $1700 in parts, and I have a spreadsheet somewhere with all the components, plus alternate options, listed out by cost and weight in grams. Portlanders think that in order to commute here, you don’t just need a bike – you need to have a commuter style. Only flat bar road bikes are allowed, EXCEPT if you have bar-end shifters for your drops. You MUST have disc brakes, 32mm 700c wheels, and Gator Skins. Nutcase helmets are preferred, but any skate-style helmet is acceptable. You will literally DROWN unless you have full fenders front and back. A back rack is mandatory, and it should either hold a milk crate on top (best) or a single pannier (not quite as Portland, but still jaunty).

Don’t even get me started on clothing.

Amortizing out all my costs, I’d be shocked if I spent over $50 per year for everything I need to get almost everywhere in the city, and also to points well beyond (including several century rides). Not including beer, of course.

What Portlanders think that? You should see the wide variety of bikes & gear in the Lloyd Cycle Station. It’s all over the spectrum.

What do all Portlanders wear? I’d like to make sure I’ve got the right uniform.

Gatorskins may not be necessary, but changing a tire in 38 degrees with cold and wet hands is a real PITA (esp if you have a schedule to keep).

9… I haven’t fully agreed with you on a comment in 5 years. I fully agree with this one.

I’m blushing. Thank you.

And just so you don’t think it was a slip up on my part, here’s an elaboration on that theme right here – from three years ago:

https://bikeportland.org/2015/07/07/guest-article-biking-cheap-145985

In my experience it costs about $500 per year, including rain gear, warmies, bike, tires–everything to operate a bike for regular commuting in PDX.

Ugh. This is why we can’t have nice things in Portland, everyone wants their opinion on every unrelated issue. Just build the protected bike lanes already. Everyone can use them equally.

How do you protect bike lanes in intersections?

Stop cars.

Or delay them with differential signals.

Start by getting rid of judges who think bike lanes offer no legal protection in an intersection.

I wasn’t claiming anyone was defending the current policies. I’m advocating for defining what the problem is before we drop billions to intervene. “because it’s illegal” doesn’t meet that threshold for me. I think that illegal immigration being elevated to such a level of important problems to solve is a result of being told it’s a problem and nothing else.

Ok, sure, the problem is pretty obvious. We have an election tomorrow. And by setting an extreme position on the issue, our president can draw his political opponents into an argument where they sound like they are defending illegal immigration, which is a losing position, both morally and politically.

But, that aside, the illegal part of illegal immigration is a legitimate problem. It is not, in my estimation, our most pressing issue, and would not be where I would spend our money, but then you didn’t choose me to be your president, so I have less say in setting our priorities than he does. Sadly.

Vote Kitty 2020!

I appreciate your clarification, bendite, and agree with you.