“There is no simple or singular solution.”

— City of Portland

The Portland Bureau of Transportation has released their annual Traffic Crash Report and the results are alarming but not surprising to anyone paying attention. The report paints such a troubling picture, even Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler noticed it yesterday. “These statistics are devastating,” he tweeted. “Portlanders deserve safer streets, roads, and freeways.”

He’s absolutely right. He’s also in a position to do much more about it.

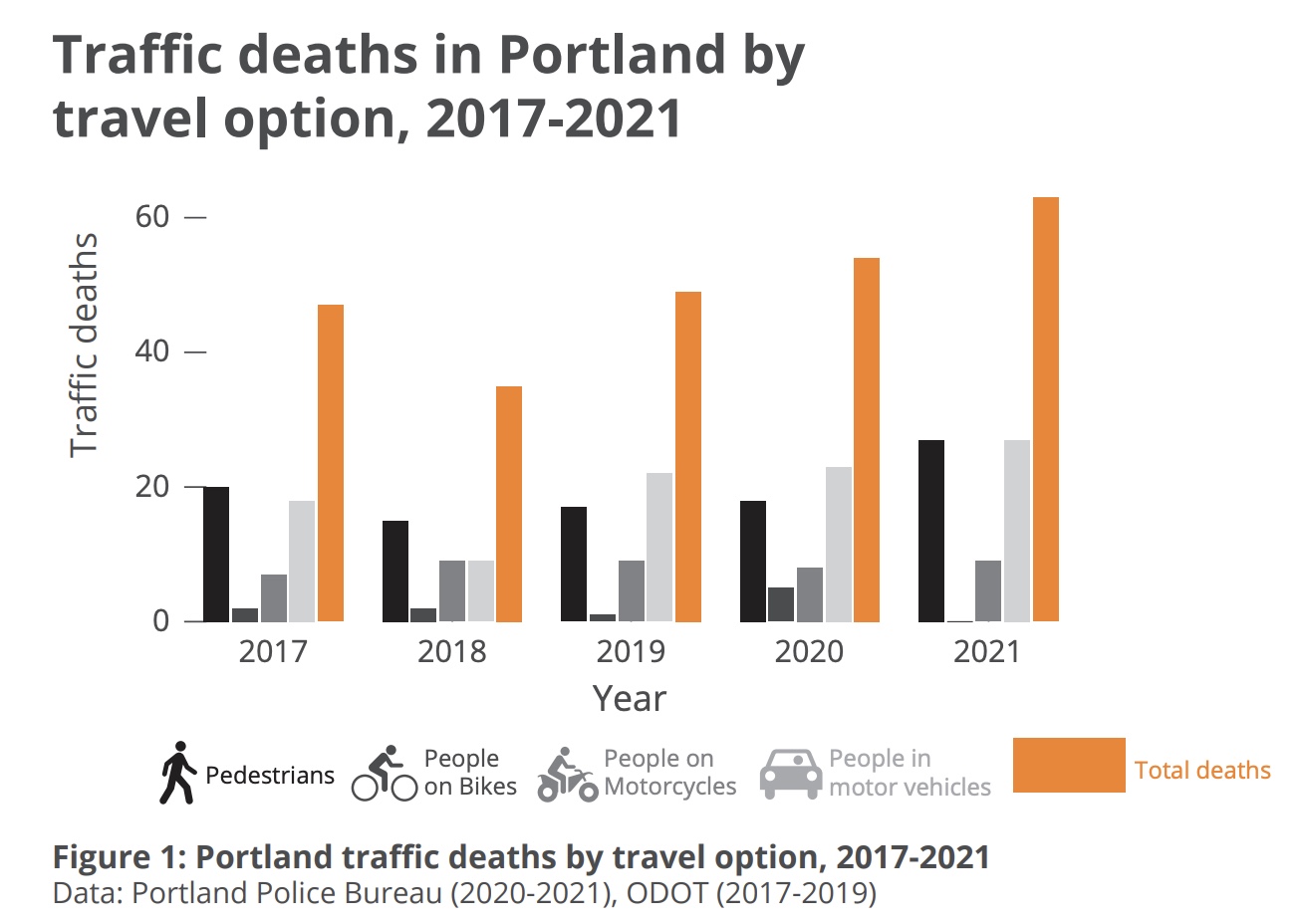

According to PBOT’s report, 63 people died on Portland roads in 2021: that’s the highest number since 1990.

“This is a new and unexpected circumstance requiring our focus and attention,” the report states.

Last year, PBOT said the 54 traffic deaths that occurred in 2020 was “unusual and tragic.” But despite PBOT’s framing, historical stats show a clear trend upward.

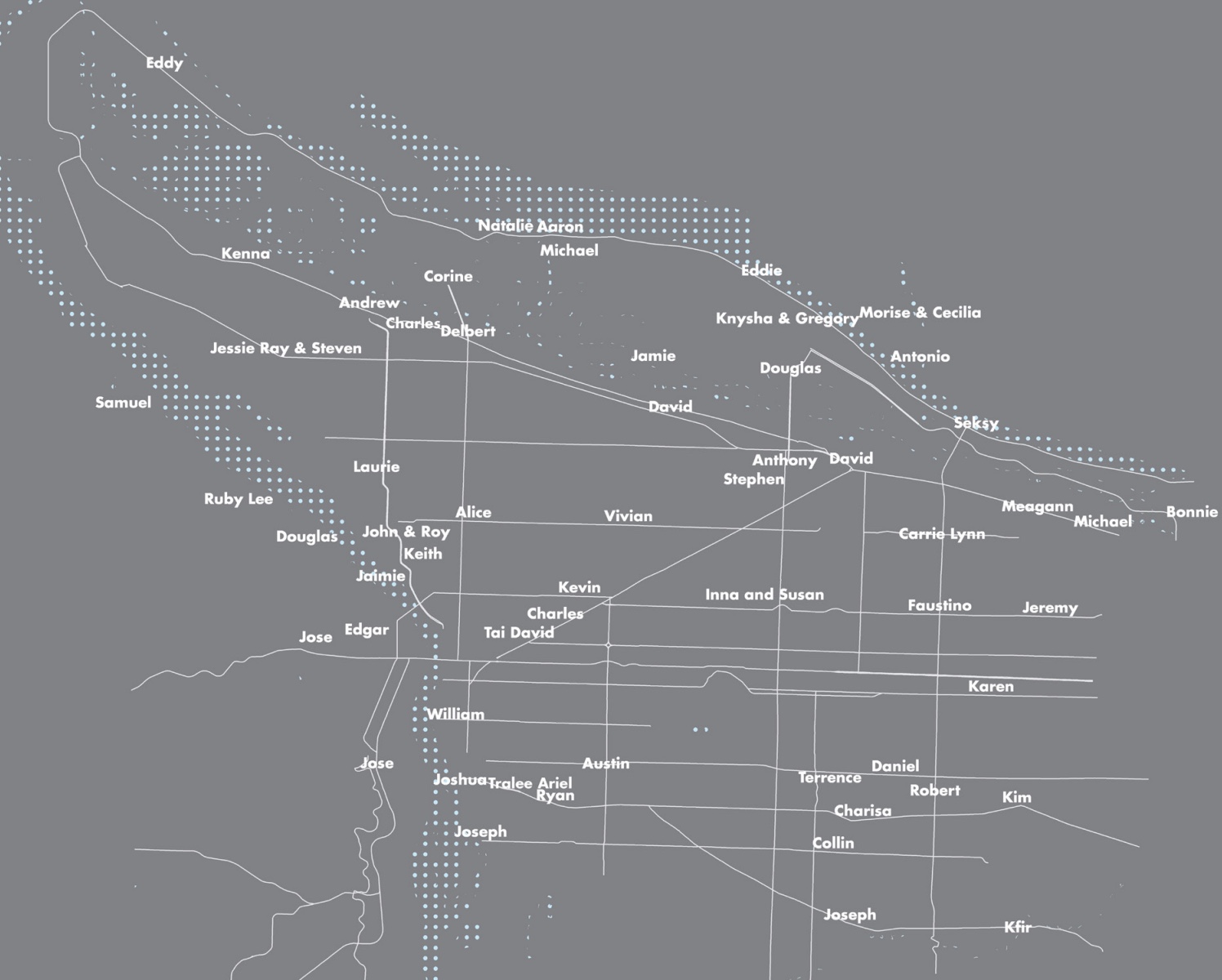

We’ve been tracking the numbers all year (see our Fatality Tracker for the comprehensive list), and it has been apparent that although Portland’s goal under the Vision Zero program is to eliminate traffic deaths by 2025, we’re headed in the opposite direction.

19 of the 27 people killed while walking were homeless. That’s 70% of the pedestrian fatalities and about one-third of the total.

The report says 60% of the deadly crashes occurred on the 8% of Portland streets that comprise the “High Crash Network,” a list of 30 most deadly streets and intersections. Many of these streets are in low-income communities and communities of color, like in east Portland. And just over half of all traffic deaths recorded by PBOT in 2021 happened on highways and interstates owned and controlled by the Oregon Department of Transportation, a significant jump from previous years.

A particularly alarming statistic in the 2021 report is how many of the people hit and killed while walking were people experiencing homelessness. 19 of the 27 people killed while walking were homeless. That’s 70% of the pedestrian fatalities and about one-third of the total.

PBOT has not tracked housing status before, so we can’t compare this year’s numbers with past statistics. But in the report and a Twitter thread outlining its details, PBOT says that it will take steps to address this alarming disparity by expanding its partnership with the Multnomah County Public Health Department, Portland’s Urban Camp Reduction Program and others to “explore collaborative approaches to increasing safety for Portland’s most vulnerable community members.”

Advertisement

“Complex social factors connected to lack of shelter, medical care and social services are contributing to the recent spike in traffic deaths,” PBOT stated Wednesday.

It should be noted that homeless camp sweeps ordered by Portland’s Urban Camp Reduction Program haven’t proven to successfully help homeless Portlanders find permanent shelter in the past, and instead can be even more harmful. Moving people around without a plan of action may put people further in harm’s way, especially if they’re forced to stay in neighborhoods with street designs they’re unfamiliar with.

Other findings in the PBOT report include that deaths from hit-and-run crashes more than doubled, with 14 people killed in 2021, compared to an average of 6.3. 13 out of 14 of those deaths were people walking.

(Photo: Jonathan Maus/BikePortland)

Pedestrians made up 43% of 2021 traffic fatalities, which is a jump from 38% last year. The annual number of people killed while walking from 2017-2020 was 17, but in 2021, that number jumped to 27. Thankfully, nobody died while bicycling in Portland in 2021.

[Opinion: We’ll never have safe streets if we continue to make safe choices]

The report says that “speed and impairment continue to be dangerous contributing factors in deadly crashes in Portland” and cites World Health Organization data that when average speeds increase 1%, the risk of fatal crashes goes up by 4% and the risk of serious crashes rises by 3%.

It acknowledges that many Portland streets have speed limits at or above WHO-recommended urban speed limit of 30 miles per hour and says that 78% of people died in crashes on streets with speed limits higher than 30 miles per hour.

Recent data from Portland State University’s Transportation Research and Education Center found that posting 20 mph signs in residential areas didn’t do much to make car and truck drivers slow down, but as we reported in 2020 there was a significant reduction in top-end speeding. PSU researchers say more drastic measures, like changing street design, should also be implemented to make a stronger impact on speeding.

PBOT’s addition of concrete barricades on residential streets is a step in that direction.

Portland wasn’t alone in its dramatic rise in traffic fatalities: this was a state and national trend. From data currently available we can see that traffic deaths increased 18.4% nationally during the first half of 2021 compared to the first half of 2020. Statewide, there has been a 15% increase in traffic fatalities from 2020 with almost 600 people dying in traffic crashes.

Despite this alarming uptick, PBOT says it is encouraged by recent announcements of the United States Department of Transportation committing to addressing traffic violence on a federal level after Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg called traffic injuries and fatalities a “national crisis.”

Our local crisis is not new. It’s just become so severe it’s finally working its way into the broader public and political consciousness.

Read the full 2021 Traffic Crash Report here.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

And yet PBOT still refuses to install stop signs at intersections until there are enough accidents. Even uncontrolled intersections don’t get stop signs. I get that there are psychological reasons not to have a stop sign every block in that drivers will start to ignore them. Still, how is it that I live on a street that goes eight blocks with zero stop signs in any direction? At least the potholes seem to help slow some people down.

The main street into my neighborhood is 1 mile long, nearly straight, with zero stop signs. You can well imagine the speeding that goes on.

The side streets do have stop signs feeding into the main street. Guess how many people actually come to a full stop and look both ways? Very few as they are so concerned about beating a car onto the street that might delay them 10 seconds.

As a heavy pedistrian user of my neighborhood I definitely noticed the uptick in folks ignoring some of the basic laws in the past couple years.

I only wish we had potholes to slow them down.

Hi there Taylor/Jonathan,

I’m going to quibble again with the characterization of “20 is plenty” as not doing “much to make car and truck drivers slow down.” The study looked at about 130,000 individual speeds on the “before” leg. The number of drivers going over 35 mph (1.11%) decreased by about 50%. So, back of the napkin, it fell from about 1,400 drivers to 700—with a confidence interval of 95% (that’s statistically significant). Those going over 30 mph fell by about a third. Those are the drivers you want to slow down, this is a solid result.

But Lisa, let me quibble with your view of the stats and whether the reduction is even relevant. I’d argue that the people you are slowing down are the ones already obeying the law. The ones you NEED to slow down are the ones who NEVER follow the law. And anyone who rides a bike or walks or spends any time on the road outside of a car knows that speeding in Portland is out of control right now – not among the people who were already obeying the law but among the scofflaws who know there is virtually ZERO enforcement of traffic laws. Your quibble about the efficacy of “20 is plenty” is a distinction without a difference, IMO.

Fred, it’s not “my view” of the stats, it’s just the data. People going over 35 mph in a residential district are not obeying the law. “Distinction without a difference?” Not so, the difference can be calculated, with a high level of significance, to be about 700 fewer cars travelling over 35 mph in residential areas because of “20 is plenty.” (Over the period of the study.)

I’m not following you. The drivers going over 35 mph in neighborhoods are not following the law and more importantly are going at speeds that are very dangerous to pedestrians. Reducing their number by half even if they’re still going over the posted speed limit makes the neighborhoods safer. The same goes for people going over 30.

People going slower while still technically going over the posted speed limit is still a safety benefit. I’ve noticed something similar on 82nd people aren’t going 30 mph but most of them are going under 40.

I’m one of those that follows the law for 20 mph in my neighborhood. You should see the number of people who get upset when they are behind me. I notice it mostly from the parents that are dropping off/picking up their kids at the neighborhood school.

I sometimes think about driving a circuit through my neighborhood to slow people down, but then I figure someone will get triggered and do who knows what.

I live in Bend and the average speed on ‘back streets’ is probably in the low 30s, but sometimes over 40. As Bend has grown, but added almost no new major street infrastructure, traffic volume has more than doubled the past decade. Drivers now ‘hunt’ for a quicker way around bottlenecks. Of course, anyone living in a city knows that phenomena. The last time I asked, Bend had two, yes two traffic teams, and that is for a 24-hour day. There is rumor that there are now three teams, but that is for a city now in excess of 100,000. I have never, never once, in 20+ years seen traffic enforcement on back streets. Not even streets that house schools.

I was truly stunned by the homeless pedestrian fatality rate, until it dawned on me that, Of course, the homeless’ primary form of transportation is on foot. It would be interesting to do a quick study of just how much of the walking population count is homeless. I am certain that they walk a whole lot more than the population in general.

I think the combination of walking + being forced to stay in dangerous areas (in terms of cars – think shoulders of interstates, high volume arterials) + mental health struggles really makes for a population that is extremely at risk for getting killed by motor vehicles.

Yes. There’s a composition effect! I don’t think it should change the policy response (*get people housed!!!!!!!*), but it should be totally unsurprising that homeless people are over-represented.

I wonder if, in part due to stay-at-home Covid caution, as well as the discomfort some people feel about walking around town these days, the ratio of homeless pedestrian miles traveled vs housed pedestrian miles traveled is even more exaggerated in the last year.

These interwoven crises are a real indictment of Portland’s ability to solve problems.

Substance abuse is also a factor with homeless pedestrian fatality rates. My bike commute has me on paths near and through homeless camps. There are times that the individuals do alarming and unexpected things that require me to take evasive measures. If I were driving I would not be able to stop or turn quite so quickly.

Thank you for this reporting, Taylor. Sobering stuff.

The most disturbing fact from the report is 13 of the 27 pedestrian deaths were categorized as a “Hit and Run.” This shows a blatant disregard of the law and a minimal compassion toward other members of the community. The mindset of a person to leave a fellow human behind after causing harm (intentional or not) tells us more about the climate on the roads in PDX than the raw numbers themselves.

Agreed. One might even call it sociopathic.

How many of these hit-and-run drivers were liberated to leave by the city’s failure to enforce license plate laws? If they’d been required to have license plates, would they have driven as recklessly? Or felt as free to flee rather than render aid?

Oh – as a pedestrian – how I wish it were 2011 still…in many ways.

Three words to ponder for Portlanders concerned about traffic fatalities:

“NO TRAFFIC ENFORCEMENT”

This city needs to install more traffic cameras, YESTERDAY. Automated speed and red light enforcement are affordable, have fewer unintended consequences (such as traffic stop shootings), and don’t require as many police officer hours (which we don’t have anyway, because officers are burned out, have the “blue flu”, or they just don’t want to work here).

Won’t happen as long as Joanne Hardesty is in charge. First she was against cameras (they would somehow be discriminatory) and now she has put the process in slow motion by attempting to remove sworn officers from the citation process. It may be better (cheaper, etc) to do this but I think this attempted removal has more to do with her anti-police bias than a desire to actually enforce our traffic laws.

She testified in favor of civilian review of the automated cameras. She’s not slowing the process down, the legislature is now the impediment.

We need to do both:

None of the most egregious and dangerous “traffic moves” I’ve personally witnessed in the past months would have triggered cameras, either because they were so bizarro or because they happened in places no one would consider setting up a camera.

So while cameras may help, they are no substitute for humans patrolling and keeping their eyes open.

Agreed.

Agreed. We need both cameras and cops. The Joanne Hardesty concept that traffic enforcement is bad needs to be jettisoned along with her as an elected official.

Isn’t is probably far more likely that these statistics indicate that we are not sweeping remotely enough? It can’t possibly be the solution that we need to sweep less and allow the homeless to continue to just reside wherever THEY want, which is obviously at great risk to them.

Sweeping camps is the Sisyphus boulder of solutions to homelessness. If that is our only solution we are condemned to toil for a lifetime. I have heard nobody suggest that they like seeing tents scattered throughout the city, but constantly sweeping tents, at great cost, just moves the problem to a different street. Criminalizing their existence in order to incarcerate them(AKA the 90’s approach) is very expensive and a violation of their human rights. Housing first, then treatment, is the long term cost-effective solution… or we can just keep pushing our boulders around the city until the end of time.

Sweeping camps is not our only solution. Terminal 2 at the Port was a great solution. We could have had a lot of people there with wrap around services and transit provided for a fraction of the cost of housing first utopian visions of grandeur, but that was squashed by the non-profit industrial complex and the activists as inhumane. It took forever for Wapato to be used as a shelter, all again due to the non-profits and activists keeping it from being a logical solution. The level of misplaced compassion in this city is insane, people would rather homeless live outside on bike paths, under bridges and in doorways to deal with their addiction and mental health issues alone all while confronting violence and abuse regularly, just because there isn’t a housing unit to place them in this minute. But yeah, you’re right, sweeps are just the worst.