Welcome to the week.

Before I share our news roundup, I want to thank all of our subscribers, advertisers, and supporters. BikePortland exists because businesses buy advertising and our readers step up with financial contributions and monthly subscription payments. If you are a regular reader — or if you understand the vital role community journalism plays in a healthy society — please join the effort to keep this trusted local news source alive. Become a supporter today!

And with that, here are the most notable stories our writers and readers have come across in the past seven days…

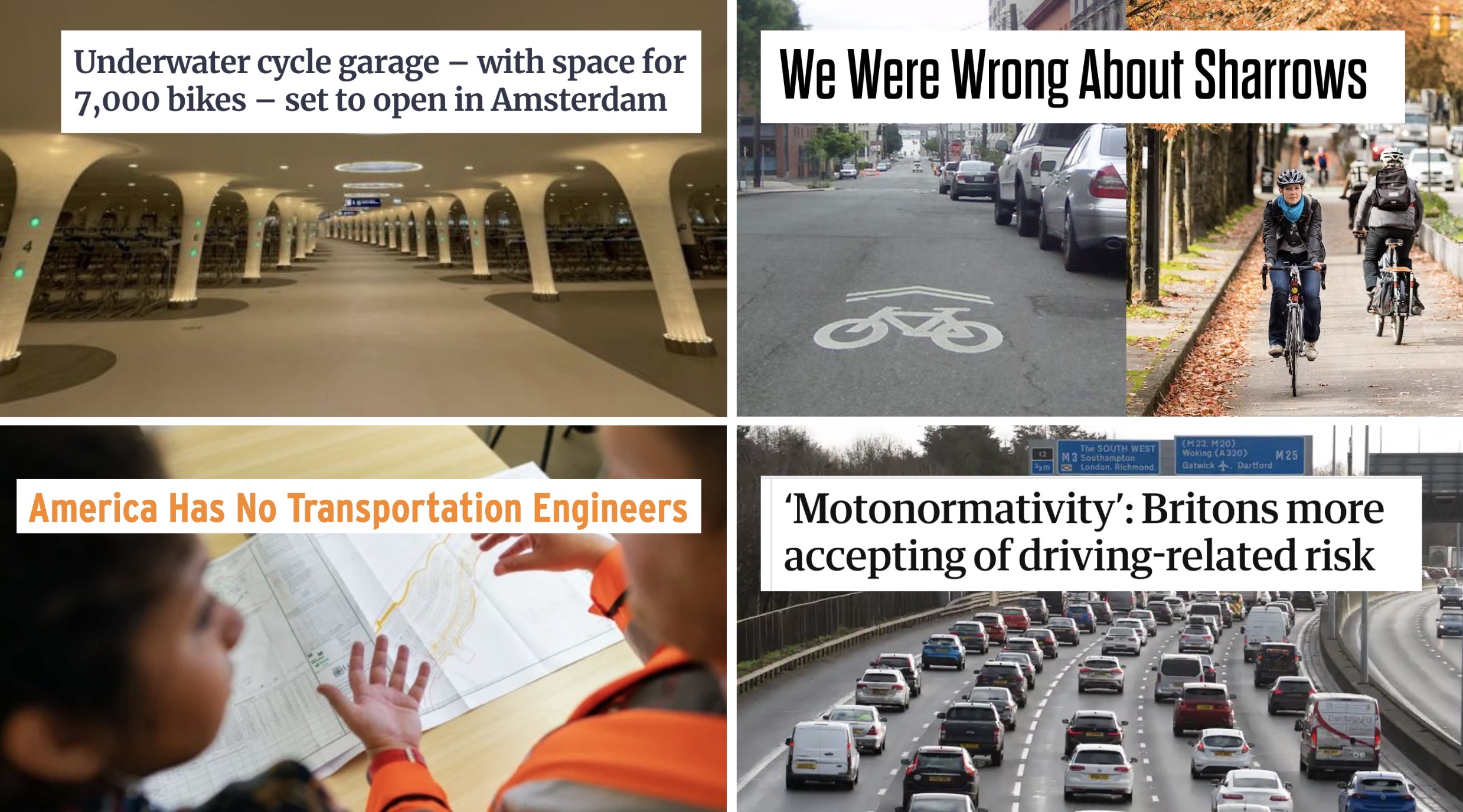

A.k.a. “car brain”: Authors of a new paper that looks into the psychology of car drivers have coined the term “motonormativity” to explain how social norms and unconscious bias make too many people unable/unwilling to address road deaths and crashes. (The Guardian)

Nail in sharrow’s coffin?: A veteran bike advocate admits that pushing sharrows back in the 1990s was a very bad idea because they don’t work (except for wayfinding like Portland uses them for) and they give empty credit to policymakers who install them. (People For Bikes)

Diversion works: A new study from London shows that neighborhood streets with diverters reduce car traffic but do not lead to a commensurate increase in nearby larger arterial roads. (Forbes)

From Stumptown to Gravelland: A Portlander has created a website full of routes that let you ride to popular local destinations “the gravel way.” (VeloNews)

Radical vs practical: A major debate of our time is how fast we should expect society to change in response to major crises like climate change. In transportation, that debate often plays out how one sees the role of EV-cars as a solution. (Boston Globe)

E-bike subsidy: Nashville, TN is the latest city to consider a cash-back program for people who buy e-bikes. Using federal COVID relief dollars, the program would offer rebates ranging from $300 to $1,400. (WPLN)

Amsterdam’s latest: One of the world’s cycling epicenters is just messing with us by building a bike parking station with 7,000 stalls that will be completely underwater. (Road.cc)

The engineering problem: Turns out one of the big problems in fixing America’s roads lies in the fact that most transportation engineers are ill-equipped for the job. (Next City)

Avoid these five states: Statistics reveal that the states of Texas, California, Florida, Georgia and North Caroline accounted for nearly 40% of fatal traffic crashes nationwide in 2022. (Yahoo)

Thanks to everyone who shared links this week.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I liked that article about transportation engineering. As long as universities crank out transportation engineers who have no real understanding of how traffic and transportation work, we will continue to crank out highway expansion projects in the name of congestion relief.

If you’re interested in a historical account of how automotive interests used academia in the early 20th century to create the modern highway-industrial complex, I’d recommend Fighting Traffic by Peter Norton (https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262516129/fighting-traffic/)

Yes, the Netherlands also has two other helpful things going in its favor:

most traffic engineers, transportation planners, politicians AND car drivers also bike weekly if not daily rides…which helps educate them as a ‘consumers of bikeways’ vs ‘spectators of bikeways’; anda CROW manual, the national design guide for transportation cycling has been a countrywide resource since ~1970 with updates (I got my first copy in 1996) versus our 2010s NACTO guide optional to AASHTO/ FHWA guidelines plus each state DOTs regulations.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CROW_Design_Manual_for_Bicycle_Traffic

Berr’s engineer training article should also include the more typical scenario: most local cities / counties now hire consultant traffic engineers on either project specific contracts or on-call time and materials contracts. This is a reflection of both workload AND need for specialized skills. This can minimize some of the very real problems he points out, BUT the old saying applies here too for traffic engineering / transportation planning: “garbage in / garbage out”. If the city county supervising planner / engineer is weak in this area or skill set they can propose solutions and approve final construction designs that are very poor or dangerous once constructed.

I liked it, too. It aims right at the “I’m an expert and you’re not/leave it to the experts” attitude that rears up so often here and in meeting or presentations about street design issues.

One of the worst impacts of the engineering education system is that it misleads people who go through it into BELIEVING that they’re experts. (It’s not just with engineering, either–same thing happens in other fields.) That leads to not listening to input that would be valuable to a project.

Luckily it’s not universal. I really appreciate running into people (not just engineers) on projects who realize they don’t know everything. Open-mindedness is undervalued.

About the five states… I’m always skeptical when people throw out stats like that, but those states only have 34% of the US population. Interestingly, when you look at states with the highest per capita road fatalities, none of those states are in the top five. So the real truth is that those states are more deadly than average and also more populous than average. The actual worst states for fatalities are: Mississippi, South Carolina, Alabama, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

This data is much more useful:

https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/state-by-state

The gist is, don’t drive on rural roads, especially at night. Rural roads with uncontrolled intersections are incredibly dangerous. High-speed “stroads” are a close second.

As a North Caroline resident, I appreciate Jonathan’s innovative new spelling – it sure beats North Clackalak.

Regarding diversion works in London. The reason for the reduction in local road traffic without an increase in boundary road traffic is not hypothesized in the article as far as I can tell. My speculative hypothesis is that the traffic that declined was local residents making local trips, such as dropping children to school or making a trip to the local shops. With the diverters in place, these trips may have become more cumbersome to achieve by car and more practical to make on foot or by bicycle. If my hypothesis is correct (no guarantees), then this would be a win-win in the sense that active transportation that increases an individual’s activity is better for their health in the long run, all other things being equal.

Generally in the past research on road diets (and in my direct experience in Vancouver WA)…about 10% of the corridor traffic “disappears”…choses a new route, combines trips, or mode shifts.

RE 5 Deadly States:

Someone noted in the story comments that the 5 named states represent 34% of the US population and 37% of the road deaths. Considering the number of rural highways in these states this doesn’t seem crazily out of line. I’d be curious to know (but not curious enough to find out) how New York would compare if you subtracted out NYC.

So, sharrows are useless (except for wayfinding) – but advisory bike lanes are going to save us.

Is it any surprise that 40% of the traffic fatalities are concentrated into 5 of the top 10 populous states with 32.6% of the total population combined with heavy, heavy car dependent setups?

Sharrows: This is clearly written directly about PBOT, right?:

Sharrows didn’t fail b/c they don’t work, they failed because the local DOTs and the state’s respective DMVs never mounted a proper education and enforcement campaign directed at motorists, explaining to motorists what sharrows meant and how they were expected to drive on streets with sharrows installed.

It’s not the sharrows’ fault or shortcoming that most motorists don’t know they are required to yield the right of way to cyclists in the lane in front of them, that is the fault of the DMV, for failing to properly educate motorists.

I think of sharrows as an incomplete solution. If it is not paired with traffic calming and traffic diverters to discourage through car traffic, then it deserves all the criticism we can level at it. I love the Portland greenways, and really miss them in Tigard. What “greenways” we do have are just sharrows – and they suck.

One thing I like about sharrows is that they embolden me to ride in a more lane-centered position because “I’m just following orders”. Riding out in the middle of the lane is usually safest.

The transportation engineering article suggests a reasonably easy long-term strategy for the Portland metro area. PSU could create a transportation engineering major at PSU to train the next generation of traffic engineers, inspired by the Netherlands model. OIT might do the same.

If ODOT and local DOTs around the region are willing to offer jobs to “transportation engineering technicians”, PCC could develop a program to train and certify them.

Those programs could also offer evening classes that would be available to current transportation engineers, as well as continuing education.

It would take a few years to develop and implement such programs, but they could produce real results down the line.

I disagree. I think Sharrows are a very important step in getting drivers more bicycle aware. I probably would not have taken the lane over the St. Johns bridge Sunday if they had not been there. Of course I would not do this during rush hour, yet. I do, however take the lane on Sharrowed neighborhood streets on a regular basis. Living on a grid in North Portland, an impatient driver can easily find another route around me. So far, drivers have kept a safe distance behind me. Of course if I did have an impatient driver behind me, I would let them pass at my earliest convenience. And if it were a psychotic driver, I would hop onto the sidewalk as soon as I heard the roar of their engine, or the thumping of their stereo. I want to be seen, not stupid. I believe most drivers will actively avoid hitting a cyclist if they see one. Except for the Texas rolling coal incident, it seems to me that the drivers in bicycle collisions never even noticed the cyclists that they hit.