How can a city encourage affordable housing residents to use transit and shared bikes and scooters more often? Results from an ongoing Portland Bureau of Transportation pilot program and a new report from Portland State University suggest one way to do it: make it free.

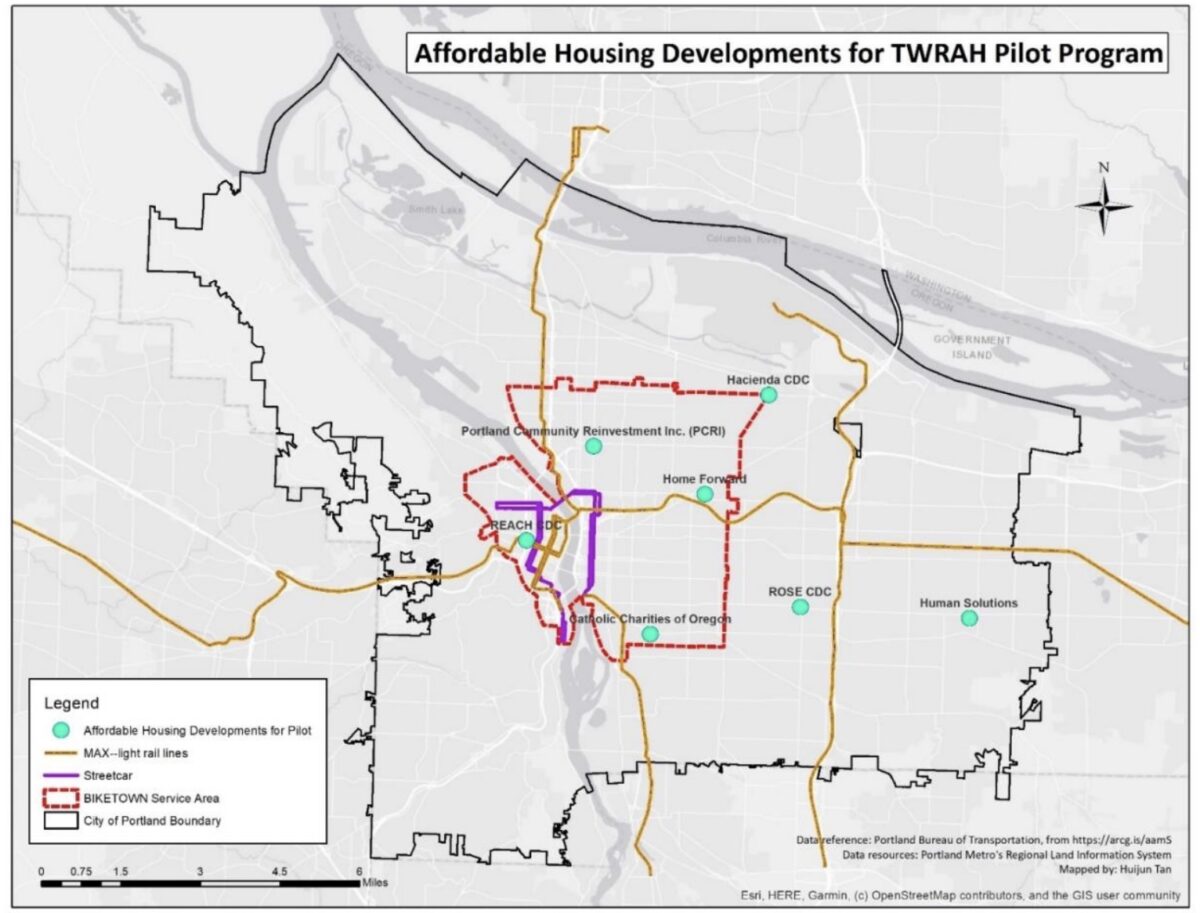

Since PBOT’s Transportation Wallet for Residents of Affordable Housing (TWRAH) pilot program launched in 2019, hundreds of residents of affordable housing across Portland have tested the hypothesis that removing cost barriers is a crucial way to make our transportation system more equitable. Now the program has been further validated by a new, federally-funded report from the Transportation Research and Education Center at Portland State University.

Other cities across the U.S. have implemented similar programs, and the idea of “universal basic mobility” (UBM) has recently become a hot topic. A 2018 Bloomberg CityLab article suggests that “the right to freedom of movement…[is] not merely a human right, it’s the foundation of a healthy democracy.” Not only would access to a basic level of mobility improve one’s individual quality of life, the UBM framework suggests, it’s also instrumental in creating less car-dependent places with healthier communities and thriving economies.

The TWRAH pilot is now in its second phase. The first phase, which ran from late summer 2019 to early 2020, provided 500 people living in affordable housing with a prepaid Visa card loaded with $308 — the price of an annual TriMet reduced fare pass — to spend on transit of their choosing, including TriMet, e-scooters, Biketown and ride-hail services like Uber and Lyft.

Advertisement

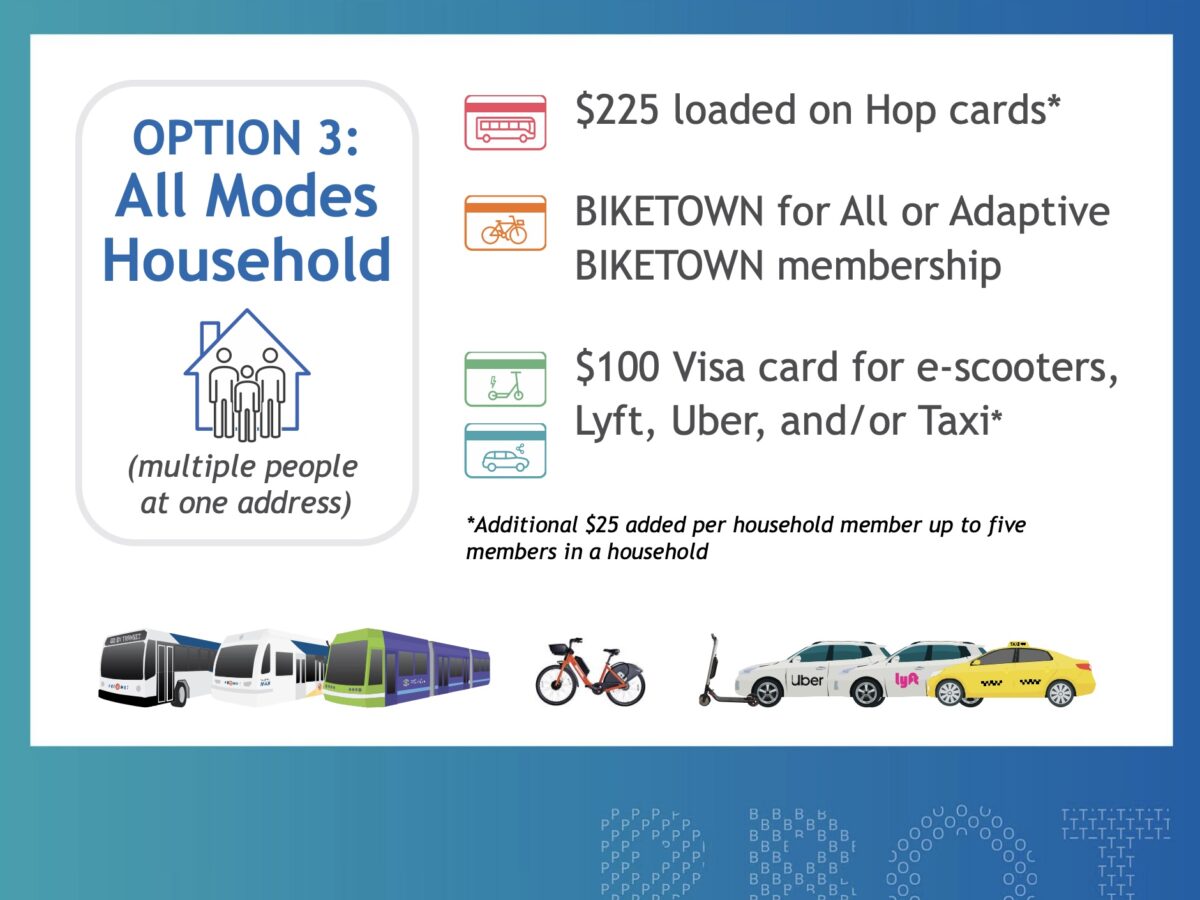

The second phase of this pilot program, which began in late summer 2021 and is ongoing, provides people with more opportunities to cater the Transportation Wallet plan to their needs, whether they want to explore riding e-scooters, Biketown bikes or stick to TriMet. The program has also expanded to accommodate multi-person households, encouraging each member of a family or household to use the transit offered.

The TWRAH pilot isn’t the first time the city of Portland has experimented with a subsidized model to incentivize people to get around without cars. This pilot was modeled on PBOT’s original Transportation Wallet program, which began in 2017 to provide people who frequent some of Portland’s most car-congested areas the opportunity to access significantly reduced rates for non-driving modes.

Through this original Transportation Wallet program, people who live or work in Portland’s Northwest or Central Eastside Industrial Parking Districts can access reduced rates for TriMet, Portland streetcar and Biketown. All it takes is $99 — or trading in your annual parking permit — to receive almost $700 to spend on non-car transportation.

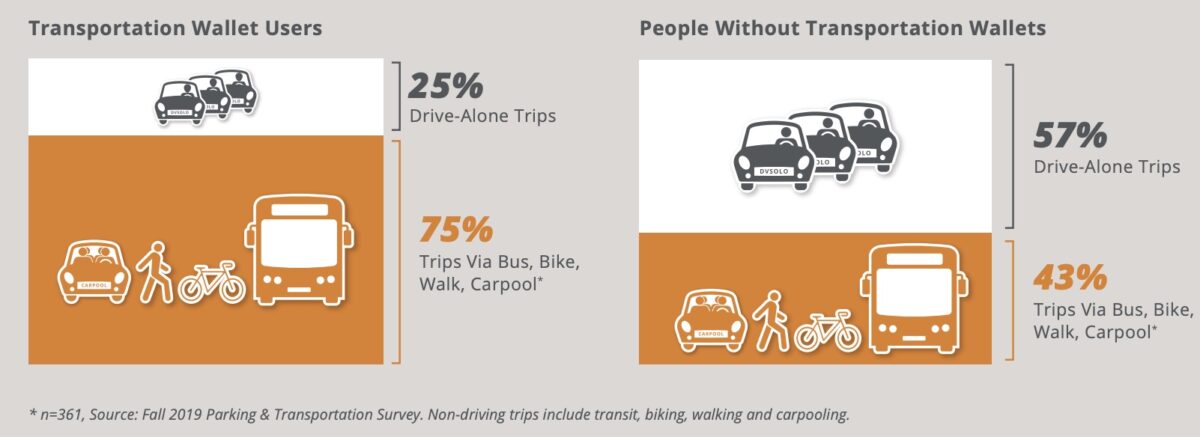

According to PBOT data (PDF), there were 4,000 Transportation Wallets in circulation from September 2017 to November 2019, 60% of which were received in exchange for annual parking permits. Almost a third of PBOT survey respondents said they drive less as a result of this program.

Along with simply providing funding, TWRAH project managers at PBOT say it has also been important to eliminate other barriers that might prevent people from utilizing new methods of transportation, like how to find and use an e-scooter or bike share bike.

“The TWRAH funds ended up being a totally fungible source of income… The money that would’ve gone toward transportation could go to something else.”

— Nathan McNeil, TREC at PSU

Both Transportation Wallet programs aim to encourage people to expand their transportation options. But Nathan McNeil, one of the PSU researchers who evaluated the first phase of the TWRAH pilot, points out that most of the participants in the program directed toward residents of affordable housing were already using public transit. 71% of the TWRAH participants interviewed in the PSU evaluation didn’t have a vehicle to begin with, and many were using TriMet already.

For them, having their mobility subsidized was a source of stress-relief, giving them a little more room in their budget: 32% of the participants surveyed in the PSU study said the best thing about the transportation wallet was money-related.

“The TWRAH funds ended up being a totally fungible source of income that helped out people’s bottom lines,” McNeil says. “The money that would’ve gone toward transportation could go to something else.”

The ability to use the Transportation Wallet funds to subsidize existing TriMet usage is an important part of the program. But the majority of participants surveyed in the PSU report said they did try to use different modes of transportation that they wouldn’t have used otherwise — an insight that shows the importance of funding and educational outreach.

Skeptics of universal basic mobility need only look to the people anonymously quoted in the PSU study for reasons why everyone deserves the ability to get around easily. And car sympathizers should hurry to find an explanation for why owning an expensive motorized vehicle provides more freedom and independence than owning a subsidized transit card.

“I can go wherever I want without [thinking about] where I will get the money to ride the bus or the train,” one participant said.

Incentive Program for Residents of Affordable

Housing in Portland, OR, by TREC at PSU)

It’s also clear, however, that more big-picture work will have to be done so people can ditch cars entirely. Three of the seven affordable housing providers PBOT worked with on phase one of this study are located in east Portland, which doesn’t have adequate e-scooter and bike share coverage yet, and isn’t as dense with TriMet options, either. 69% of East Portland residents used ride hail services more than once, a figure that drops down to 44% for people living elsewhere.

Still, mass transit and micromobility advocates shouldn’t worry that a few free Uber rides will make people scoff at car-alternatives. 83% of east Portlanders in the study said they used TriMet more than once, and 63% said they took mass transit more than 15 times. One study participant — whose residence location is unknown — talks about ride hail and cab services more as an occasional treat than a trusty transportation standby, saying it was “nice to have cab fare for rainy days, emotional days and for animal appointments.”

PBOT officials say the future of this program is yet to be determined, and more information will be available after the second phase of the pilot is completed in 2022. As it stands however, the program appears to be one effective way to identify barriers that prevent people from being as mobile and low-car as they’d like to be.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Excellent report and great coverage, thank you!

And this isn’t to diminish the need for the Transportation Wallet at all, but relatedly, TriMet fare should just be $0. A very small percentage of their revenue (less than 10%) comes from fares, and transportation should be a public service like roads and parks and street lighting and libraries and fire stations. Having to means-test free access to public transit is a lot of unnecessary overhead.

Metro should follow the lead of Corvallis, Wilsonville, Olympia, Walla Walla, Kansas City (Boston may be next with mayor-elect Michelle Wu) — and Tallinn, Kuala Lumpur, Dunkirk, Luxembourg and other world cities — and just make public transit free of charge.

In spring of 2020 after we (my employer) relocated from close in eastside to Clackamas I started riding the train a lot more (my bike commute went from 10.5mi 1way to 20mi 1way).

Then I stopped.

The 1st and 2nd Red Line out of Beaverton at that time were literally rolling homeless camps. People sleeping across 4+ seats, including with their legs across the aisle. Panhandling. Crack smoking. I saw it all in a very short time. From April 2020 to June 2020 I rode 200 miles/week to avoid the trains. If I were a less dedicated active transportation person I would have purchased a car.

Now, imagine I were a driver attempting to reduce my driving and I got on a train like that.

The only reason this changed was a concentrated enforcement action by TriMet, and the main tool they had to remove most of the campers from the train was non-payment of fares.

Subsidize them, by all means, even to the extent of qualifying people getting free transit and a bit of extra for last mile micro-mobility or ride-share/cab to take an animal to the vet.

I’m all for it.

But having had experience of Fareless square back in the day and more recent experience with this and the fact that portions of a possible bike route for me are unusable due to homeless camps, simply removing fares from transit is a *terrible* idea.

Abuse of the system is an issue in many cities, but as you have already attested fares are not an effective way of keeping homeless people from taking shelter on our transit system, so it makes very little sense to maintain a fare structure that creates many negative outcomes to accomplish something that we already know fares are incapable of doing.

what part of “and the main tool they had to remove most of the campers from the train was non-payment”

Was not clear? This situation was unsafe. I’m 6’2″ and fairly buff. My 4’10” partner is *not* I did not feel safe, how do you think she would have felt?

You want people to drive less? Letting the MAX become like the stretch of the I-205 path between Burnside & Stark is *not* the way to go about it.

In addition to Bjorn’s excellent point, I find this line of argument just bizarre. The solution to houseless folks finding shelter on public transit is to…raise more barriers to people using transit?

Like, why not charge $50 a trip — get rid of the poor! Let’s also require you to be able-bodied so we can get rid of slow accessible boarding, and drop the bike carriers because that slows things down too. And why not demand proof that someone is traveling to a legitimate destination — no more lazing-about taking up seats from productive members of society! Then the (few) people who qualify will enjoy their wealthy chariot processions. Is that really an equitable vision of public transit?

The presence of houseless (or whom you perceive to be houseless) people on public transit is, to me, so blindingly obviously a symptom of a broken system. The solution isn’t to sweep undesirable people out of buses any more than it is to hide them away from one part of the city to another. The solution is to house more people.

Surprisingly to you, I would guess, is that when people have more reliable and accessible public services — like, you know, free public transportation — they are less likely to end up experiencing houselessness in the first place.

If we took your logic to its rightful conclusion, there would be no public services. Smelly people in the library? Start charging admission! Drug users starting fires? Tell the fire department to refuse to put them out! Someone sheltering under trees in a public park to escape the rain or for relief from heat? Institute required passes to local property owners only!

These kinds of “solutions” don’t address the problems, they just hide the symptoms.

Like any other form of public good, public transit should be free and accessible to all.

Hmmm, you failed to actually read the post. Good job.

Here’s what I read:

The “main tool” we as a society have is to ensure that “campers” have places to live, and not use high barriers to a public good to solve a problem that is to a large extent the result of people facing high barriers to livability in the first place.

You’re making a critique, rather than engaging on whether zeroing out user fees would harm Portland’s transit system and the people who depend on it.