(Photo: J. Maus/BikePortland)

Yesterday the Portland Bureau of Transportation released the final report of their East Portland Arterial Streets Strategy (EPASS). This marks a key final step to an effort we reported on when it started back in late 2018.

A goal of EPASS is to inform advocates, community members, policymakers, leaders, and even PBOT staff themselves, about how best to move forward in taming east Portland’s notorious arterials.

East Portland is home to about a quarter of the city’s residents, yet suffers over half the traffic deaths. Underlying this disproportionate statistic is the fact that 28 of the city’s 30 high crash intersections sit east of 82nd Avenue.

“People have urged us to make sure we’re considering our streets as a system, not just making changes in a vacuum on each street.”

— Chris Warner, PBOT Director

The EPASS study, which covers 42 miles of the east Portland arterial network and runs 68 pages long with 10 technical appendices, has several objectives. One, it seeks to better understand the cumulative, system-wide effects of the numerous capitol projects planned, underway or completed in east Portland. As PBOT looks to make significant changes to street designs, EPASS addresses the public’s concerns around the question of “What will happen to traffic patterns when we change multiple streets in the same area?”

It also attempts to communicate with the public the process, safety findings, and best-practice interventions that have guided PBOT toward “the most appropriate and effective tools to reduce crashes while making sure people can still get to their jobs, schools and other destinations on time, whether by walking, biking, taking transit, or driving.”

Advertisement

And tucked in toward the end, the report also states that it is “decision documentation for PBOT staff as we move forward with implementation of projects and programs.” In other words, it also serves as internal documentation of the overall strategy and goals for the area, and how individual projects fit into them.

During the height of the Covid shutdown, traffic decreased by 60% in the central city, but it only decreased by 30% in East Portland.

The importance of a coordinating document like this should not be underestimated, especially in an area like east Portland which is benefitting from over $200 million in safety projects under several different programs, including Vision Zero, Neighborhood Greenways, Transportation Demand Management and the East Portland Action Plan. The EPASS report should help keep everyone on the same page — PBOT staff, neighborhood advocates, the community, even curious media like us. It can be viewed as a meta-document for the area and a resource for basic facts and project history.

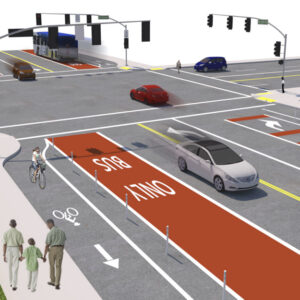

The report recommends new lane configurations (reducing the number of travel lanes) on a third of the arterials they studied. This accommodates more or better protected bike lanes, pedestrian islands, center turn lanes, and bus-only traffic. The EPASS project website has a video which explains that traffic signals at intersections are the “pinchpoints,” which is why road diets will not significantly increase travel times. The Corridor Summaries Guide section of the report has a two-page summary of vital stats for each of the 11 corridors analyzed (above) and it shows recommended street cross-sections. This alone will be a useful resource. Currently there are 15 funded safety projects underway and PBOT is seeking funding for an additional nine projects.

There were a few findings in the report that caught my eye. During the height of the Covid shutdown, traffic decreased by 60% in the central city, but it only decreased by 30% in East Portland. This is consistent with the bifurcation of Americans into “essential” workers who had to show up to their jobs working the register, delivering food, treating patients, providing care, keeping the community safe, and those of us who work can work from a home computer. The difference also speaks to the different land-use patterns and safety of infrastructure for non-driving trips. The natural experiment provided by the pandemic has helped PBOT model what travel will look like in the future and has led the bureau to predict that east Portland will continue to be car-dependent relative to inner-Portland neighborhoods.

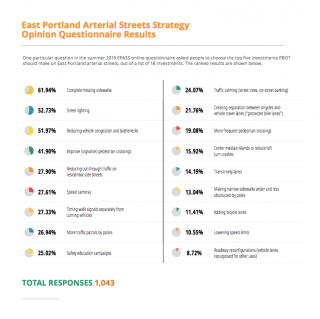

Also, only 22% of respondents to a 2019 online survey shared in the report (above, right) considered protected bike lanes to be a priority investment, and only 11% prioritized adding new bike lanes. And scoring last, at a little under 9%, the public really did not see road diets favorably. It was interesting to notice that, despite the survey findings, new bike lanes or better-protected bike lanes were part of the proposed cross-sections of all of the corridors studied.

— Lisa Caballero, lisacaballero853@gmail.com

— Get our headlines delivered to your inbox.

— Support this independent community media outlet with a one-time contribution or monthly subscription.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

If there are less lanes at the traffic signal ‘pinch points’ the line of cars waiting for the light will be longer and consequently wait times for the lights will be longer and it will most definitely increase travel times. Just sayin’

You clearly didn’t watch the video, check it out from 1:45 on. The road diets are mid block, but they retain multiple lanes at the light. So traffic moves in a line at a slower/safer pace, and then stages at the light. Thus you avoid the classic case of getting passed by a speeding car, only to catch them at the light.

I’ve driven the new configuration on Glisan, and the extra lanes at the lights are no where near long enough to hold all the cars waiting at the light during rush hour, and some of them are turn only lanes as well.

That happens all over east Portland anyway. Have you driven on Stark during rush hour? 4 lanes the entire way, and it will back up for miles at the major intersections.

It’s almost like there’s no more room for single occupancy vehicles and some other solution has to be thought of…

BTW, the bike lanes on outer Glisan are now basically in the gutter and are full of hazardous drainage grates, poorly patched utility cuts, debris and other obstacles for cyclists, and I rarely see anyone using them.

Given that PBOT has “owned” nearly all East Portland streets since annexation ended in 1991, I’d like to see the appendix that lists all the excuses PBOT will state for doing absolutely nothing about making timely improvements over the next 30 years.

…and another appendix for the past 30 years also.

I think a lot of it is that many of the people who live there don’t want these kinds of improvements. They want more car capacity. It’s easier to make safety improvements in inner neighborhoods because the residents there are more supportive.

Hence the problem with Portlands ‘public engagement’ form of government. It’s rare to get people who are passionate about changes for safety. If you tell most people that you are going to make an intersection safer, they say ‘cool’ and move on with their life. The type of people PBOT ‘engages’ with are the people who have a full blown meltdown if you want to take their sacred parking or marginally slow down a street.

PBOT should but wont move to a model of evidence-based safety infrastructure regardless of community input. The bar should be extremely high to kill a safety project, like a true hardship.

We can’t let NIMBYs or businesses decide how safe the area approximate to where they live or work is going to be for everybody else who lives/works there or simply needs to pass through. It’s absurd.

FWIW, businesses on SE Hawthorne changed from opposing bike infra in the late 90s to ostensibly supporting it in 2020, and it didn’t make a difference to PBOT either way. Also, all traffic from outer SE PDX heading downtown has to funnel through the inner city neighborhoods at some point.

FIFY:

“It’s easier to make safety improvements in inner neighborhoods…because the residents there [are mostly white, mostly wealthy, and mostly expect to benefit from racist privilege].”

That is the conventional wisdom. I don’t think it’s accurate.