(Charts: BikePortland. Data here.)

In the days since President Obama signed the new five-year FAST Act into law, we’ve been talking to several local experts about how it might affect Oregon.

Is this a win? Well, it depends on what you’re starting from.

The simplest answer, according to experts at the state DOT and the regional planning agency Metro, is that it’ll continue the status quo.

That’s in contrast to the previous bill passed in 2012, known as MAP-21, which was “pretty chock-full of policy changes,” according to Trevor Sleeman, the Oregon Department of Transportation’s federal affairs specialist.

“MAP-21 was a pretty policy intensive bill and in comparison, you’re right, the FAST Act is relatively light,” Sleeman said last Thursday in response to a question about the general outlines of the bill, which Sleeman was still in the process of reading. “It’s probably more of a funding-focused bill, generally speaking.”

Metro’s Ted Leybold offered a similar summary.

That’s fair enough; getting any sort of action out of today’s ideologically entrenched Congress is an accomplishment on some level, and that’s what happened over the last month. But if it’s just a funding bill, let’s look at the funding.

Advertisement

The bike-related number that’s been kicked around most often in the last two weeks is the funding for the Transportation Alternatives Program, a pot of money, mostly from federal gas taxes, created by MAP-21 to pay for things like:

on- and off-road pedestrian and bicycle facilities, infrastructure projects for improving non-driver access to public transportation and enhanced mobility, community improvement activities, and environmental mitigation; recreational trail projects; safe routes to school projects; and projects for planning, designing, or constructing boulevards and other roadways largely in the right-of-way of former divided highways.

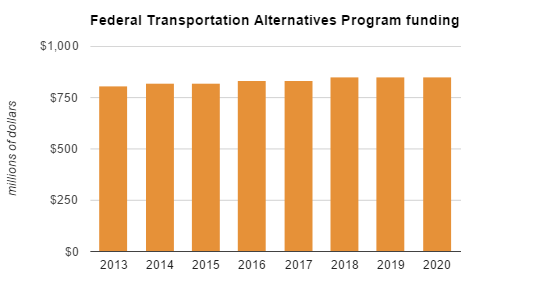

That’s not everything the federal government spends on bike infrastructure, but it’s one of the biggest chunks. In a post on Dec. 2 about the transportation bill, the low-car advocacy group Transportation for America described it as “one of the few programs where funding doesn’t grow with the overall increases in bill.”

Here’s the TAP funding agreement that’s been described by some as a victory, rising from $820 million this year to $835 million next year and $850 million from 2018 through 2020:

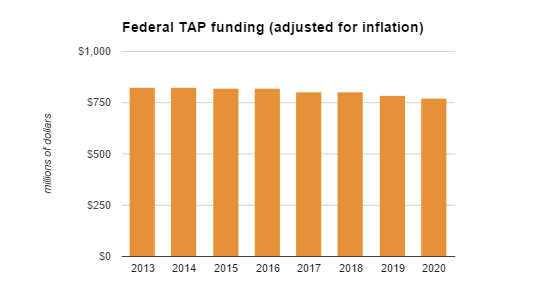

Now, let’s look at it after adjusting for inflation. (This is just inflation from the general consumer price index, not for actual construction projects — if infrastructure costs rise faster than consumer prices, the value of $850 million will decline faster, and vice versa.) This chart is in 2015 dollars. Inflation for future years assumes the Federal Reserve’s target rate of 2 percent; this is the level they’ll be trying to keep inflation at when they probably raise interest rates this month.

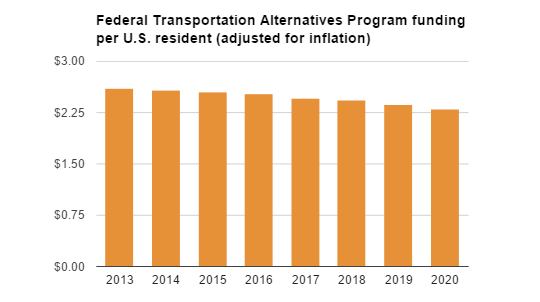

And here’s what the chart looks like after adjusting for inflation and population (this is the same chart as the top of the post):

And does the increase in TAP funding even keep up with the growth in the number of bike riders in America? Not exactly, says Caron Whitaker, the VP of government relations for the League of American Bicyclists:

.@BikePortland @BikeLeague increase in $ for bikes doesn't keep up with demand, its incremental improvement #bikechat

— Caron Whitaker (@CaronWhitaker) December 11, 2015

Is this a win? Well, it depends on what you’re starting from. Eleven months ago, an oil-industry-funded coalition of advocacy groups was sending a shot across Congress’s bow by declaring that “Washington continues to spend federal dollars on projects that have nothing to do with roads like bike paths and transit.”

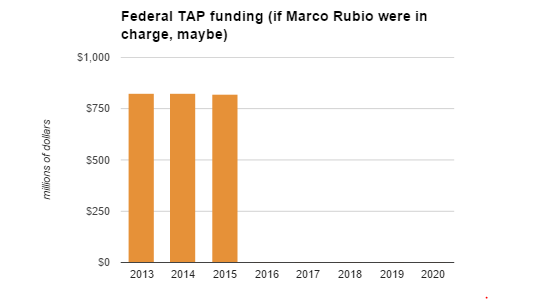

This perspective is captured by the transportation policy of, for example, presidential candidate Marco Rubio, who says he wants to cut federal gas taxes by 80 percent and “free states from the strings that come attached to federal funding,” presumably including programs such as this one. So if that view had prevailed in Congress this year, these charts might look like this:

If that happened, would ODOT keep spending meaningful amounts of money on bike-specific improvements? Probably somewhat. Another virtue of the new bill is that it lets states and regions spend money on bike infrastructure if they want to, even if it’s not marked specifically for bike infrastructure.

How many other DOTs would do so? How much?

As with all legislative sausage-making, it’s hard to say what might have happened.

Tim Blumenthal, president of biking advocacy group PeopleForBikes, said Tuesday that with the bill, the country has “turned the corner” on the debate over whether bike infrastructure and programs deserve federal funding.

“It provides five years of steady funding for bike projects with the type of long-term certainty that we haven’t had since 2004,” he said.

— Learn more about the FAST Act in this summary prepared by Toole Design Group.

(Disclosure: PeopleForBikes is my other half-time employer, but I rarely interact with the team that lobbied on this bill and didn’t follow their work. This is written as third-party journalism and isn’t informed by my PeopleForBikes work.)

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

The Interstate Highway System is built. Devolution would make perfect sense at this point if Rubio’s plan weren’t such an obvious “drown it in the bathtub” small-government ploy.

Taxpayers need not weep every time adjusted spending is flat or down. Bureaucrats don’t even mind keeping the budget excuse in their back pocket.

The legislative priorities concern me, though. With spend-spend-spend enginerds at ASCE have data showing TAP’s proportion of highway spending dropping almost perfectly by 10% over the course of the bill. In five years, will alternatives be just 90.03% as important as they are now?

To follow up on the Rubio graphic…I would assume the funding cliff would take at least 1 year to kick in, so 2016 would likely have some funding as it trailed off.

PS. It is too bad that libertarians and small government types do not embrace bike projects for urban areas (cut all the suburban car projects) and use the savings for their rural areas. The bike should be their perfect vehicle. But it is not (for now).

Todd, Id disagree with the notion that the bike ought to be the perfect mode of transport for conservatives and other small govt types. We tend to prioritize liberty and to limit undue govt intereference in our lives. Hence, our favorite mode of transport is whatever maximizes our freedom of movement.

Further, conservatives do, I think encourage mutli-modal transportation plans…at the state and local levels, though. Our small govt focus is on a smaller federal government. Thats why its often hard and misleading to apply what Republicans and conservatives at the federal level are saying and simply say thats what they believe across all levels of govt. I suspect that Rubio would say that the less money being pushed to the fed govt for transportation is more money available to the state and local levels. The federal government is horribly bad at national transportation policy and even worse as an inefficient funding conduit for transportation projects. We ought to all want to limit the number of $ getting to the federal govt. Additonally, it makes zero sense that Iowanss are paying for bike paths in Oregon. Another reason to very narrowly tailor the federal govts role in transportation to purely national transport systems and infrastructure.

Can you provide a few examples of very conservative states that have good multi-modal transportation policy? I have never been to one, personally. I’m a bit intrigued.

MN, UT, WI are all in LAB’s top 10:

http://bikeleague.org/content/ranking

MN and WI have voted to elect the democratic candidate for the past few decades now. Even in 2004 when Kerry lost by a decent margin nationwide.

I’ll concede Utah, but add that they have some unique policies in that state to begin with. They definitely don’t fit the “conservative” mold in America.

Personally I wouldn’t describe Minnesota or Wisconsin as conservative, but Tennessee is a standout, too.

What no conservative states have done, as far as I can tell, is internalize the idea that there is a tradeoff between pleasant driving and pleasant everything else.

For what it’s worth, BeavertonRider, I think you and I might personally agree on some of this:

http://portlandtransport.com/archives/2014/07/actually-lets-bother-fix-federal-transportation-funding.html

Alas, one of the biggest shortcomings I see is not necessarily in funding, but in a lack of bicycling as a stakeholder in routine maintenance, such as repaving and repainting. I see SO many places – and have had so many conversations around – where small, minor variations in paint would undo lane width variations, driver and bicyclist uncertainty as to roadway positioning, better delineated yield/merge locations, etc. There are simply no real guidelines – and yes I include NACTO – to tell engineers and project managers how to undo age-old paint placement and replace it with decades of bicycling (and driving) experience as more and more people take to the road (doing both).

I say this as I just rode through a freshly repainted section (here in Santa Clara) where nothing changed, despite a multi-page proposal (with twenty-seven eight-by-ten color glossy photographs with circles and arrows and a paragraph on the back of each one of them… 😉 pointing to NACTO and CA MUTCD standards, reviews and approvals by city and county BPACs and engineers, and multiple assurances the problem (lane flaring at the expense of substandard bike lane width) would be addressed… two months of phone calls and meetings and emails (and it’s not even my ‘real’ job)… yet the old stripes went right back in. And more people will be hit here – mark my words. (For the curious, this is the intersection of Homestead and Lawrence Expressway, a few blocks east of the new Apple HQ).

I don’t wonder why California cities are being successfully sued by victims’ families. And I couldn’t help but think of Jeffrey Donnelly…

Sorry. Keep fighting the good fight.