Is America’s latest bike boom coming to an end? Or is it just moving to different cities?

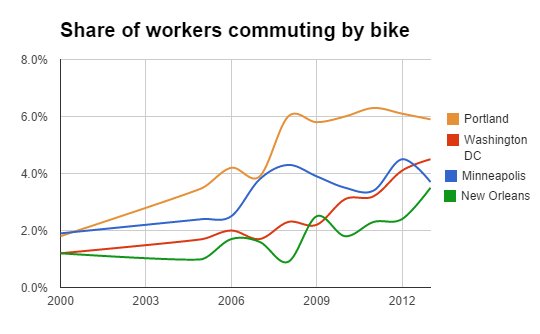

2013 Census estimates released Thursday show the big cities that led the bike spike of the 2000s — Minneapolis, Seattle, Denver and, most of all, Portland — all failing to make meaningful changes to their commuting patterns for three years or more.

Meanwhile, the same figures show a new set of cities rising fast — first among them Washington DC.

The nation’s capital seems to have shot past Minneapolis, Seattle and San Francisco in 2013 to achieve the second-highest bike commuting rate among major U.S. cities: 4.5 percent.

Portland’s bike commuting rate ticked down to an estimated 5.9 percent in 2013, from 6.1 percent in 2012 and 6.3 percent in 2011. Statistically speaking, it’s been mostly unchanged since 2008. Though Portland has added 10,000 net jobs since 2011, the Census surveys estimated that it’s actually lost about 600 daily bike commuters.

Instead, Portland residents’ additional commutes since 2011 seem to have shifted toward three line items in the Census: carpooling, walking and “other,” which includes motorcycles, skateboards and taxis.

Bike share credited for DC growth

As we’ve written before, bike-commuting rates from the Census aren’t a very good way to compare cities to each other, because they depend so much on where city borders happen to fall. But looked at over time, they’re pretty good at identifying which cities are improving their transportation systems and which aren’t.

“The plateau of the perennial leaders is certainly evident,” said Darren Flusche, policy director for the League of American Bicyclists, in an interview.

“Bike share flipped the script and showed that normal people in normal clothes biked in DC.”

— Darren Flusche, League of American Bicyclists

Washington’s bike commuting rate and its network of painted bike lanes grew gradually until 2010, when the city launched one of the nation’s first and most successful bike sharing systems. In the four years that followed, DC’s bike commuting rate has doubled.

“Bike share flipped the script and showed that normal people in normal clothes biked in DC,” said Flusche, who moved from New York City to Washington in 2009. “It’s bike share that changed the way people think about the bike. Because those bikes are so heavy and slow, it’s not about being an athlete. It’s just a more practical choice.”

Advertisement

Some cities see big biking gains, but many stall

(Photos: J.Maus/BikePortland)

In any report about Census commuting surveys, it’s worth emphasizing that they ignore all trips except the ones to work and back. Also, they require people to choose a single primary commute mode.

DC isn’t the only city once thought of as a second-tier bike town that saw big gains. Bike commuting also seems to have doubled in the last four years in New York City, which Bicycling magazine this month named the country’s No. 1 bike city.

NYC’s bike commuting population swelled from about 36,000 to about 46,000 in 2013, pushing its bike-commute rate from 1 percent to 1.2 percent. (That’s up from 0.6 percent in 2009.) In Pittsburgh, the estimated biking rate jumped from 1.4 percent to 2.2 percent; in Tucson, from 2.8 percent to 3.4 percent; in New Orleans, from 2.4 percent to 3.6 percent.

Other large cities, though, were as stalled as Portland in 2013: San Francisco at 3.8 percent, Philadelphia at 2.3 percent, Boston at 2 percent, Chicago and Austin at 1.4 percent.

Nationally, bike commuting is still inching up, though not as steadily as it was in the late 2000s. It’s now used for 0.62 percent of American commutes.

“Bicycling is still the fastest-growing mode choice in the country over the past decade,” Flusche said. “That’s great. [But] if you look at these numbers, they’re still pathetically small. … We still don’t have an American city that’s built a complete network, that’s done more than a symbolic job of building bike infrastructure.”

City of Portland: ‘We know we’ve got more work to do’

Portland Bureau of Transportation spokesman Dylan Rivera said in an interview that “we know we’ve got more work to do.”

“That’s why we’re continually seeking grant funding and the Our Streets PDX funding to make our streets safer for everyone,” Rivera said.

He added that the city believes the programs it currently uses to increase biking rates, all introduced or expanded under former Mayor Sam Adams, will pay off eventually.

“We think that continuing to grow our Safe Routes to School program and our high-crash corridor program will make the streets safer for pedestrians, bicyclists and transit users,” Rivera said. “The kind of outreach we do with Sunday Parkways is crucial to introducing people to bicycling as a fun transportation option as well.”

Rivera said bike sharing is also “a really important tool” for giving people a chance to experiment with bike transportation.

“We’re still working hard and hopeful that we’ll be able to launch a bike share system,” Rivera said.

I asked Rivera if he thought rising central-city rents might be a factor in pushing potential bike commuters further from their destinations, or whether Portland’s improving economy might be encouraging people who might once have biked to start using cars. He withheld judgment on both issues.

“If anything, Portland is adding bike-oriented development,” Rivera said. “When you have mixed-use neighborhoods well-served by transit and safe biking and walking infrastructure, you tend to have more active transportation use.”

“These sometimes take decades to observe,” he added. “But over the long haul, that’s proven to be the case.”

Interested in these issues? Join us at City Hall at noon today, where I’ll be moderating an expert panel featuring Portland Bicycle Planning Coordinator Roger Geller, Alta Planning + Design principal Jessica Roberts and Bicycle Transportation Alliance Executive Director Rob Sadowsky to discuss whether Portland really deserves to be slipping in national rankings. Bring a lunch! It’ll be a fun, freewheeling discussion.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I suspect that Portland has reached its bicycling limits because of lack of comprehensive bicycling infrastructure. Lots of dedicated bicyclists, but Portland is still a car city.

I have a different hypothesis. What if this is just going to be near the ceiling of what we are going to attain? What if given all the infrastructure in the world the same percentage of people are still going to choose their car or transit? (I would venture that the latest PSU study might be starting to hint at this)

This is a possible reality in America that we just might have to face.

I agree with this idea – the car ideal is so entrenched in our culture at this point.

Bingo, Dave! There is a limited number of adults who 1. Are physically fit enough to bike 2. Know how to bike 3. Like to bike 4. Have a job that is amenable to bike commuting 5. Live close enough to work to bike.

Once we face facts- we can move ahead. IMHO- the cycling advocates should concentrate on getting kids on bikes. Instilling a love of biking- whether for fun or transport- happens at a young age. My kids use bikes as transport- but I taught them to bike by three or four. Me- I still remember when the training wheels came off and I could fly down the road.

I agree to some extent. We should start building our bike infrastructure like crazy now to support families/kids on bikes. We should be actively working to reduce car-subsidies that support single-occupancy car trips- they are too expensive, unsafe and inefficient. I realize we have a car culture, but that can change, and it is likely to evolve as with generational shifts.

What do you propose to reduce car use and how will that strategy be viewed by the majority of Portlanders?

I don’t agree with all your points. But I think #3 is the biggest limiter. If people have a choice, most will just choose the car.

Which point did I get wrong?

I guarantee that more than 6% of the city fall into one, some, or all of the categories #1,2,4, and 5.

Okay. I was just listing my perception of reasons my fellow Portlanders don’t ride. I don’t pretend to know what percentage of people fall into each catagory. It’s just that many people have one or more barriers, or prefer something besides a bike for transport. I think that 6% may be a natural barrier of sorts for the time being.

Fair enough. I as just pointing out that I think that for many people the part about just not wanting to ride is the predominant reason.

If you had asked someone in October 1908 what percentage of trips would be made by automobile in 2008, I doubt even Henry Ford himself would have guessed the car would become so dominant.

People would have reasonably objected that only 25% or perhaps 50% of trips could be by car, due to the high cost of the vehicle, the high cost of petroleum, limited supplies of parking, and the small number of people who knew how to drive. And why would anyone drive a car for simple trips to the grocery store or school less than 1/2 mile a way? Certainly women, children and the elderly would not be fit to drive a dangerous, unreliable vehicle.

It took 50 years of building our cities expressly for car access and convenience to get to where we are today, where 85 year olds with memory and vision problems continue to drive, 15 year old kids are dropped off at high schools, and the majority of simple trips to churches, grocery stores, even the post office, are made by car.

The Netherlands reversed this trend by greatly improving access and safety for bikes. It did this even though car infrastructure is pretty nice, parking is often free, and most families own a car.

Portland can get to 25% of trips by bike if people feel it is a safe, easy, cheap and enjoyable way to get around.

Huge difference being that from the horse/carriage to the auto was a HUGE upgrade in speed and convenience. Switching from a car to bike kind of goes the other way. It’s definitely not going to be the no brainer choice that the auto originally was.

The Netherlands reversed this trend by greatly improving access and safety for bikes. It did this even though car infrastructure is pretty nice, parking is often free, and most families own a car.

*The Netherlands instituted truly draconian excise and gas taxes that were expressly designed to discourage low-occupancy motoring.

*The Netherlands made de-autofication national policy. This involved cessation of highway building campaigns, removal of highways/ring roads in urban areas, the creation of traffic-calmed/free areas in many urban locations, and elimination of parking in urban centers.

*The Netherlands also instituted legal reforms that make motorists automatically liable for collisions with active transport.

*Active transport receives truly massive subsidies including individual cash grants to purchase bikes.

IMO, if the USA taxed gas to ~$9 a gallon we would see active mode share surge. Unfortunately, the ongoing global tragedy of the commons that is low-occupancy motoring continues to receive massive subsidies in the USA.

the 15 yr old kids being dropped off at school–theres one to work on. See it every day at Franklin HS. I also see a large number of youth walking and taking the bus. But the drop-offs are the key to congestion on Clinton/Woodward in the mornings for sure.

There is a ceiling of course, even the most bike friendly places in the world (Copenhagen, Amsterdam) dont go beyond 50%.

But 6% is absolutely not the ceiling. Look at some of the smaller places, like Cambridge MA, or David, CA, and you see rates in the teens. These are the same car-loving Americans, and yet more the twice as many of them are choosing to bike.

In cities that are predominated by universities. Not exactly comparable.

I don’t think that hypothesis is true. To be true, you’d have to assume that U.S. culture were so different from European and Japanese culture as to make 6% the ceiling rather than 20-25-35% as are commute rates in many European and Japanese cities. Sure, we’re different, and advertising has made cars seem great to many Americans, but I don’t think American exceptionalism explains such a huge gulf. There’s advertising all over the world. The vast difference in our gas taxes, parking prices, car fees, bike infrastructure, etc. seems like a much more reasonable hypothesis for the majority of that difference in commute rates between Portland and many European and Japanese cities.

So, we’d have to assume we’re different, and then you say we are different?

We’d have to assume we’re SUPER different to justify a “max” mode share that’s less than a quarter of other cities in Europe/Japan based solely on cultural factors. I just don’t think that’s reasonable. There are tons of policy factors (which I listed above) which I think are more explanatory than cultural factors.

Based on the European people I know, the transportation “culture” isn’t that different. Driving there isn’t looked down upon in high-bike-mode-share cities – indeed plenty of people would like to own cars. It’s just that driving is expensive/inconvenient enough, and cycling is convenient and comfortable enough, that biking seems like a more practical choice for them. That different calculus, it seems to me, is almost completely because of government policy (taxes, parking, infrastructure).

I would actually argue that land use/urban planning/city development and transit differences are more factors than most of the things you listed. Huge cultural differences as well. We’re Americans: we’re basically taught to buy everything bigger, move further out and get more space.

All that is driven by government policy, too – though it takes much longer for policy to have a large impact on e.g. development patterns than on gas prices.

sure, but at some level WE are the government. So yes, I do think we are SUPER different. (We’re also an incredibly conservative county in most aspects and don’t like change)

I think we pretty much agree but are stating it in different ways. Do I think that increasing bike use (and transit and walking) and decreasing car use tremendously in Portland, much less the rest of the US, will be a huge lift? Absolutely, and it’s because of the entrenched status of the car that you identify in American land-use, government policy, and, yes, culture. Do I think we need to try, for the sake of our collective health, environment, pocketbooks, and government balance sheets? Also absolutely. Do I think that government policy is the first place to work on? Yep, I think that it’s the biggest lever that activists have to pull. Do I think that culture (defined narrowly) needs to change too? Yes, but I think that’s harder to change than policy.

Yes. Good points.

My original post was just to point out that I don’t think we can just build our way to a significant increase in mode shore (through infrastructure).

Oh, maybe you’re including taxes, parking fees, motor vehicle fees, etc. in “American culture”? In that case, I maybe agree with you, although I think nice bike infrastructure on its own could get us up to 15%ish.

A lot of these raw numbers are meaningless. If a city wants to increase bike travel, it needs to stop sprawling and stop letting the car occupy such a large part of urban space.

The important thing about “modal share” is that a large percentage of people who live in the dense inner city use their bikes. Some American cities have NO dense inner city whatsoever.

If no one in suburbia uses their bike to go to work, it’s not because of anything wrong with the bicycle. It’s the suburb that needs to be changed, for this and many other practical reasons.

The biggest gains between 2010 and 2013 were increased % walking to work. This definitely fits with your idea: all of those walking trips are short enough to be made by bike. So, if people are walking, they consider that a cheaper, easier, or safer way to get to work, vs biking.

I think it is great that more people are living close enough to walk to work, but I think they should have the option of using transit or riding a bike as well.

It’s interesting that the 2 categories to decline (significantly) were Transit and Working from Home. I suspect the latter declined due to an improved economy (more people have regular jobs, rather than trying to get by as self-employed), and Transit declined due to fare increases and the death of the free zone in Downtown.

It appears to me that the same percentage of people are driving (alone, or by car pool). The difference appears to be that more people are walking rather than riding their bike. So maybe more people are starting to live closer to work?

Lots of people work from home now.

The stats above show a lower percentage of people working from home in 2013, compared to 2010 (though it is still higher than in 2000)

Portland needs bike share and protected bike lanes. Full stop.

“Portland needs bike share and protected bike lanes. Full stop.”

This won’t happen until there is dedicated funding, and the attitude here towards the Street Fee is “no way, tax someone else.” That is sad.

I want better bike facilities and I am willing to pay taxes for them. Am I in the minority?

Yes, roughly a 6% minority if Census stats are correct. 🙁

Todd, I do not have that attitude. The street fee supports and subsidizes car trips, especially the single-occupancy commuting from suburbs! And it does this while penalizing poorer citizens and failing to incentivize alternative transportation. The Street Fee will tax TriMET and Parks! Lets raise money for infrastructure, but lets do it in an intelligent, equitable way that reinforces our goals. Lets tax surface parking lots, increase meter fees and expand metered areas, sell parking permits for more neighborhoods, increase the gas tax, introduce a sales tax, increase vehicle registration fees by weight/age, work on legislation to allow red light/speeding cameras and raise all moving violation fees. We can raise money and create safer streets at the same time. Many people have reasons to oppose that Street Fee that are not simply “tax someone else”

In general, the wealthier a person is, the more tax-averse they become. I think it’s inevitable that the pro-gentrification policies of the democratic establishment will lead to a decline in active/public transport in PDX.

It is easy to double or triple bike-commuting rates in cities notorious for some of the nation’s most congested auto-traffic: Add a few bike lanes and sprinkle in bike-share. I’m looking at you, DC and NYC.

Portland doesn’t have the auto-congestion (yet) that some of these other cities do that might push some towards non-auto use. At least Portland’s 1-person auto use is stagnant or slightly on the decline.

The only way these numbers will improve substantially is to attract to the Sunday Parkways crowd. The only way that happens is to focus on 3 things: SAFETY, SAFETY, and SAFETY. Green boxes, extra white paint, and some plastic sticks ain’t gonna do it.

We need more protected bike lanes. Plain and simple.

We also need a more proactive police department. A police department that truly takes road harassment and intentionally aggressive driving towards cyclists more seriously, that pursues and prosecutes bike theft more aggressively, and so forth.

My experience is that they’re currently not interested in either of these things in any real way, and that makes a big difference for people who are apprehensive about cycling full-time and are one negative experience away from giving up and moving back to driving all the time.

During the Great Recession, auto driving declined – not just in Portland, but in Oregon and nationally. Driving costs money, so less money -> less driving.

See charts on these pages

http://daily.sightline.org/2011/03/01/whered-the-traffic-go/

http://www.oregonlive.com/commuting/index.ssf/2014/09/portland_traffic_jams_increasi.html#incart_river

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2014/04/dot-vehicle-miles-driven-decreased-08.html

Some of this was lower employment, some was fewer unneccessary trips, and a little bit was probably shift to other modes. Even a very small percent shift in driving translates to a significant increase to other modes like bicycling, because driving is such a dominant mode. A 1% change to the 800 lb gorilla is a many 100%s change to the mouse.

Thus I think a good part of the increase in bike commuting during 2007-2009 is due to the Great Recession.

Not all of it. There are other factors. Sam Adams’ administration advocated bicycling more than Hales’ does, and there was more money available for bike infrastructure projects. But that sharp jump from 4% to 6% – I think most of that is the economic cycle.

I think, therefore, that the stall in bike commuting since then is largely due to the economic recovery from the depths of the recession. Most people avoid effort and value comfort, so more money -> more driving.

If this is right, the underlying trend of a slow increase in bike commuting in Portland is still there. That is supported by the fact that bike mode share has been flat, not declining, in the last couple years, even as driving has recovered.

To sustain that underlying trend, the city has to continue expanding bike infrastructure and otherwise making itself more bike friendly. Look, bike commuting is not all that easy. The 3 mile flat amble from close-in NE Portland to downtown on a sunny day is easy, low-hanging fruit; the 6-10 mile slog from outer east or west, maybe over hills, in the rain is not so easy, that fruit is harder to pick.

Some people think the city should actively make itself less car-friendly. I disagree: deliberately making life hard for the large majority of people who are drivers invites a big backlash, and anyway increasing congestion and cost is already making the city less car-friendly. I don’t think you have to tear down your neighbor’s house just to make yours nicer.

Other cities have different circumstances. Where bike infrastructure has gone from nil to something, bike mode can start to make the initial increase that Portland saw years ago (think NYC). Bike share can also help grow bike mode (think NYC, Washington DC). Some cities were largely unaffected by the Great Recession (think Washington DC).

We don’t need to actively try to penalize driving, but removing some of the vast subsidized and regulation that favor driving is fair and necessary.

There is no reason to have parking minimums in zoning codes, and street repair should not be subsidized by general tax dollars while the gas tax remains so low. Motorways and bridges should have tolls that pay for their maintenance, rather than being subsidized by general tax dollars.

Most importantly, some of the space currently given away as free parking or excess lanes for cars should be used for bikes and transit. There is only so much space on city streets; if we are going to make bikes, walking and transit a reasonable choice then some space will have to be taken from cars.

Fortunately, if parking, gas and bridges are fairly priced by the free market, the roads will be even less congested than now, as people choose the form of transportation that makes the most sense for them.

As biking, walking and transit use increase, the roadways will have plenty of room for people who choose to continue driving, even if some lanes or parking spaces are reused for other purposes.

None of this is penalizing driving, it’s just using limited space in a more reasonable way, instead of continuing to subsidize driving so much. We are just so used to the status quo of limitless parking and subsidized roads that a fair transportation system seems anti-car.

Just a counterpoint to your argument about general tax dollars being used for road repair…..if the vast majority of people drive to work, doesn’t it make sense that “general tax dollars” are used? You’re hitting up the majority of people with a tax that everyone is hit with. I’m also going to reiterate that I firmly believe that raising the gas tax will hurt the poor much more. As Portland gets more expensive to live in the core area, the poor are being pushed further out. Thus causing them to drive more to get to work, services, etc.

Yes, the gas tax is (somewhat) regressive. I’m pretty sure that many of the poorest people do not have cars, even in East Portland, but I’d bet car use doesn’t increase all that much from working-class to middle-class to upper-class.

Does that mean an increased gas tax is bad? In my opinion, it just means that we need to offset an increased gas tax with some sort of payments or tax credits for the poor.

Taxing everyone, including the poorest, with what almost amounts to a flat tax, to pay for motor vehicle infrastructure which only people of moderate means or better generally use, seems even more regressive than a gas tax increase to me. Taxing everyone to pay for motor vehicle use which pollutes and divides our neighborhoods also seems like a bad way to align incentives. I say we should tax motor vehicle use, which causes the vast majority of the infrastructure needs and has giant negative consequences (local air pollution, killing/maiming people, carbon pollution) to boot.

If you don’t want the gas tax to hurt the poor, than make it revenue-neutral. Problem solved.

In general I think it’s true that wealthier people means less bike transportation (I suspect Portland’s job recovery is pushing biking rates down a bit), but the economy didn’t really crash until early 2009. Portland’s big biking gains were in 2007 and 2008. That’s the gas price spike, not the recession … but the bike boom happened on a much larger scale here than it did in other cities that also saw gas prices soar. Maybe the difference is that the human and physical infrastructure were already in place in 2006, waiting for people to haul out their bikes.

The great recession started on Dec 2007 (NBER). By early 2008 net household wealth was in free fall and by the middle of 2008 personal consumption expenditures were in free fall.

http://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2011/july/impact-great-recession/

BLS data shows Portland MSA unemployment numbers bottomed late 2006, started rising late 2007, accelerated rapidly in 2008, peaked early 2010. Employment peaked late 2007, went sideways until late 2008 (while labor force was still rising), then dropped hard until bottoming early 2010.

I’d forgotten about the gas price spike during 2007. I’m sure that had an effect.

Your comment about the bike infrastructure being here and waiting for increased usage seems very plausible.

Wealthier people means less bike transportation? That strikes me as a very strange comment. Perhaps you mean that employed people are more likely to drive than the unemployed?

“I don’t think you have to tear down your neighbor’s house just to make yours nicer.”

Wise words, John. You are a good advocate for cycling infrastructure. I could see your arguments resonating with the broader public.

What happened in 2008 to make PDX and MPL level off? Did the recession just mean less jobs for people to go to?

Mode share leveled off in 2009, not 2008. Gas prices had fallen dramatically from their ~$4/gallon 2008 highs to as low as $1.75/gallon. The financial markets were also in recovery due to unconventional monetary policy.

What is the source for the numbers in this story? The link does just leads to your Google doc.

Source for the census data on commuter travel modes is the U.S. Census, American Community Survey, American Factfinder. Look at advanced search and search for table B08006 and your geographical area of interest:

http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t

Note that this is a fairly small sample, all the more so when divided down to just one city and only bicycle commuters, so almost all of the jitter you’re seeing in the data for a city for bicycle commuting from year to year is nothing more than statistical noise. For city-sized samples of bicycle commuting data you need to average 3 or even 5 years before you have enough data for the signal to cut through the noise.

In small words, don’t get overexcited about one-year up or down jumps in bicycle commuter percentages in one city.

I agree completely. The “mode share” of commute for biking seems to have stabilized presently at 6%. As a full and part time bike commuter over the last 7 years that strikes me as pretty much an asymptotic limit when thought out. Given that the average city commute is about 8 miles and the average suburban commute is about 12 miles the number of commuters for whom biking is a viable choice is limited out. Also given that the work force (take my word for it!) is aging faster than the topography is flattening out; makes it very hard to substitute infrastructure or conversely driving “penalties” to compensate. It is always a wise and efficient choice to promote biking, walking and living closer to employment centers; but none of these efforts is going to have a “silver bullet” effect on vehicle miles traveled, health, happiness, etc. There are no “bogeymen” and there are no panaceas to urban problems of congestion, pollution and high real estate prices. We just edge by one small step at a time.

I am really disappointed that there’s so much of this “glass ceiling” line of thinking here in the BikePortland (of all places!) comment section. Seems like a sign that we really have lost our mojo…

Buck up people! Imagine a better, bikier Portland! Other cities around the developed world have achieved 20, 25, 30% bike mode share and you’re saying that 6% is our fate forever because Portland is so “special”? Change the land-use, the infrastructure, the tax incentives, the culture that you think is in the way!

http://www.bikeloudpdx.org/

Thanks, Brent. And here’s a link that should pull up the table with the cities listed above. You can only link to one year at a time, so this is 2013. Change the “13” in this URL to another year to see the others.

http://factfinder2.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/13_1YR/B08006/1600000US1150000|1600000US2255000|1600000US2743000|1600000US4159000

I biked as my sole mode of transportation for about 15 years in Portland before buying a car a couple years ago. I almost never ride anymore. Why? Ultimately I just stopped feeling safe on the roads. After a while, every bike trip was a hair raising mega stressful experience. Biking wasn’t fun anymore, it felt like an arduous task and one I grew to dread. These streets weren’t made to cater to such heavy auto traffic. Without dedicated bike lanes, true bike boulevards and urban cycle tracks, I’m remaining checked out and my hat’s off to those braver than me.

I can’t speak to the particulars of your situation, but I am surprised. I took a 10 year break from bike commuting (resuming in 2012), and things are so much better now than they were in the early 2000s.

I’m not sure how worse auto congestion can make for a better bike ride, but I’ll take your word for it. Definitely wasn’t my experience as the years progressed. Lots of out of state drivers with very little knowledge of bicycle laws.. the amount of close calls grew as time progressed and eventually it just wasn’t worth it.

I didn’t notice worse auto congestion (again YMMV), but the improved infrastructure helped me, and the increased bike traffic provided safety in numbers by making the activity both more normal and something that drivers needed to be mindful of.

The first plot could be a lot better. Without data points it is hard to tell what type of smoothing you are using. Without error bars it is hard to see if the dips and rises are meaningful.

One major issue (though not the only) is that after all of these years we are still refusing to make cycling inviting, safe and accessible for the type of trips where cycling is most competitive with or outright beats other modes. Forget commuting. Focus on short and local trips. Let’s say I leave from my house near Alberta street, place a take out order at Via Chicago (20th & Alberta), head over to the Alberta Co-Op (15th & Alberta) to pick up a six pack and then head up to Vide-o-rama (27th & Alberta) to rent a movie before heading back to VC to pick up my pizza and take it home. Using Alberta street to make all of these stops makes cycling competitive with if not faster than driving when you consider parking, etc. For most people such a trip is not going to happen by bicycle because cycling on Alberta is not safe, accessible and inviting for them. The alternatives, Going or Sumner, add distance/time to the trip which makes cycling less convenient and makes driving more attractive. This is my main problem with PBOT’s focus on neighborhood greenways: they don’t connect destinations in the most convenient fashion. When I visited Copenhagen last year, what struck me most was that you don’t need a “bike map” to get around the city. You just need a regular map and you can rest assured that the most direct route to your destination will have safe and inviting cycling facilities for you.

Any particular reason you have the San Francisco info in the spreadsheet but didn’t plot it out with the others?

Five cities just made the chart look like spaghetti and I wanted to include Nola (because it’s surprising) DC (because the growth is momentous) and Minneapolis (because it’s Portland’s classic rival).

do you have a link to the ACS data?

It’s important to note that the vast majority of bike commuters in the Boston Area’s urban core are not in the city proper – so even if the city itself remained stagnant, surrounding areas might have increased – especially since the primary focus in Boston has been on areas where commuters would be coming from the direction of Cambridge/Somerville/Brookline. There hasn’t been much bike infrastructure progress in the crucial neighborhoods of Dorchester and Roxbury – and there are a still a few major gaps that restrict access from the south to the major business districts on the north side of the city – plus ACS doesn’t count “mixed modes” which is a large number of people around here (namely, bike to transit).

Here’s the link to the 2013 data I used:

http://factfinder2.census.gov/bkmk/table/1.0/en/ACS/13_1YR/B08006/1600000US1150000|1600000US2255000|1600000US2743000|1600000US415900015

For other years, you can change the “13” to something else.

thanks for posting the link for data. I know none of you guys really care about Boston, but I think it’s worth showing for comparison sake.

Here is the bike mode share for the core urban areas of Boston Metro:

Boston Proper: 2% (no change)

Somerville 7.8% (up from 3.7% in 2012)

Cambridge 6.5% (down from 8.4% in 2012 – still within margin of error – also 25% of people walk to work there)

Brookline 4.2% (2012 data only – no change from 2009)

two other urban core cities worth including, but note that they have very poor bike access into Boston and extremely high transit use – only data is from 2012:

Everett 0.3%

Chelsea 0.6%

Inner Ring Suburbs worth noting – (every place I’ve listed would fit within land area of Portland btw):

Newton 1.4% (no change from 2012)

Medford 2.1% (2012 data)

Malden 1.1% (2012 data)

Watertown 1.4% (2009 data only – likely much higher)

Belmont 1.1% (2012 data)

Arlington 2.9% (2012 data)

Milton 1.0% (2012 data – up from 0.3% in 2009)

I think the somerville jump is probably due to a whole bunch of bike lanes appearing along with bikeshare expansion within the past couple years…

Well if your neighbors house is 6 stories high, blocks the sun, dumps untreated sewage, and more, maybe it needs to be taken down a notch or two.

Sounds like SE Infill- four stories high- blocks the sun- looks like sewage …

But those are only along busy commercial streets, and are much better than parking lots…they actually house your neighors!

They are putting four story cheaply built infill houses in my neighborhood- which is not commercial.

The headlines are misleading. Maybe bicycling has leveled off in Portland, but the percentage of people commuting by car continues to shrink. This in spite of all the work ODOT does to support the asphalt lobby…

I’m surprised by how many commentators seem to dismiss the role of infrastructure. Portland had high rates of cycling DESPITE a lack of low stress bike infrastructure downtown. I think this speaks to the limits of encouragement and education efforts. If it doesn’t feel safe, most people won’t do it. If you look at Montreal, bike use there shot up once they completed a protected bike lane across the downtown, and id bet heaps of cash that the same would happen in Portland with similar connections. Given portland’s current inertia, I think it will be soon dethroned as the bike capital. Maybe DC will take the crown soon, given its network of protected lanes downtown, bikeshare, and a plan in place to link the city with many more protected lanes. Watch out Portland, DC is seriously nipping at your heels.

I’m dismissing it, but also have some data to back that up (like the recent PSU survey that showed for a majority of people NOTHING would get the to start bike commuting). There are MANY people out there, who are just not going to bike, regardless of how much separated infrastructure you build.

Sometimes, people say something that’s not true about their behavior, or people don’t have enough context to realize that something is true. Given that, in my opinion, we have no areas in Portland that have a *network* of good bike infrastructure – good enough to get people safely, comfortably, quickly, easily, and intuitively from A to B for all reasonably close-by As and Bs – I’d imagine that almost all survey respondents don’t really have a view in their minds of what good bike infrastructure looks like.

Alex, it has been shown time and time again that people are not 100 percent forthcoming on surveys- and that the level of honesty varies by country. Now, how does your argument work when we look at the “interested but concerned” respondents. How many of them are just trying to say something unobjectionable? Maybe they don’t want to admit that they would never go to the effort of buying and using a bike? Maybe they lack context too?

It is human nature to discount facts that challenge our beliefs. The data is not really supporting your vision, right now, IMHO.

The major data I’m using for context are the bike mode shares over 10% in at least 22 good-sized developed-world cities. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modal_share#Cities_with_over_1.2C000.2C000_inhabitants Until someone gives a convincing argument as to why Portland is extremely different on topography, weather, or culture from all of those cities, I’m going to continue to think that different government policy could get us a significant increase.

I think a survey of PSU students is orders of magnitude less indicative of the long-term potential for cycling in Portland than the example of tens of cities who have actually achieved high mode share.

As to why I focus on infrastructure – I think (although it’s certainly not easy) bike infrastructure is the easiest of the levers that need to be moved. The others include land-use, density, gas tax & motor vehicle fees, parking provision and pricing, and truly good public transport options. I believe all of those are much more politically difficult than bike infrastructure.

Is bike infrastructure alone what works for cycling? No, but it does appear to be one of the big factors.

Of course, from one perspective, Portland is “extremely different” culturally from those cities. But do you really think that if you plunked down Portland’s population in Copenhagen’s built environment and policy environment (things are dense and close together, bike infrastructure is great, owning/using a car is really expensive and inconvenient, public transport is a great alternative when you don’t want to/can’t bike or walk) that the Portlanders’ mode share wouldn’t shift significantly towards biking?

Interesting points, Alex. And I now understand why you focus on infrastructure- it is more feasible. Yet- your theories need to account for the last 5 years- because you are swimming against the tide. People flat out love their cars, and you won’t be getting rid of cars (or guns) anytime soon.

Portland is plopped down in the middle of the Old West, in some ways. My neighbors have trucks, chainsaws and guns and boats. Very handy when

a tree comes down, or if there’s a wounded varmint to put down. They aren’t going to start biking.

500,000 cars and the neighborhood associations in revolt. Your theory needs to account for cycling’s small numbers and the pushback against New Urbanism.

“People flat out love their cars, and you won’t be getting rid of cars (or guns) anytime soon.”

I’m not persuaded that the pegging the love-meter is all that relevant for our understanding of the future of cars. Sometimes you can’t keep the thing you love the most, not because you don’t love it enough but because its time has come. We here in the US are used to having our way, calling the shots; but our ability to make it all happen is on the decline.

You’re combining a bunch of stuff together to try to make a point, and I think it’s a little disingenuous.

None of the things you mention are contrary better bike facilities: Love of cars, firearms ownership, trucks, and boats.

As a Clackamas County resident, I’d argue that biking where I need to go for my work or errands is incredibly self-sufficient. Further, it means I can be a little less practical with my outdoor vehicle and tire choices.

And even if your neighbors don’t want to bike themselves, I’d be very very surprised if they don’t want to live in a neighborhood where people do bike and have places to bike to.

Recently did a vacation in Portland (I’m from Vancouver), as was really surprised at the lack of bike infrastructure for a place that’s often billed as a “bike capital.”

There is virtually no physical separation, the network felt disjointed and hard to navigate in places, many of the painted lanes are narrow and flush right up against parked cars, etc.

You folks have a really well developed bicycle culture, but I think way better infrastructure will be required to move ahead with mode share. It’s just too unfriendly out there for casual riders.

One factor to bear in mind with the Minneapolis downturn is that the weather could have had something to do with it. They have just gone through two winters that were unusually brutal and long even for Minnesota. IIRC last year they had foot of snow in May – and I don’t think I ever saw a snowflake in May in all the years I lived there, despite that having been before climate change started making their climate milder.

But then again, I don’t think it’s coincidence that a lot of places saw major gains in bicycling as the Great Recession hit and we saw (except for a short blip) sustained gas prices in the $3-4 range. In retrospect I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that a recovering economy, with more people working and more able to afford driving, is part of the leveling-off.

Personally, I don’t think we’re anywhere near “topped out.” I believe we have the potential to reach 20-25%. But I think we may be approaching the limit of how many people are willing to ride using the infrastructure we have.

To get to 20-25% we’ve got a lot of changes to make. But it’s worth it: the more walkable and human-scale spaces we’re going to create in doing so will provide livability benefits far beyond just getting 20-25% out of cars and into active transportation.