I’m happy to introduce the Real Estate Beat, a new editorial focus that will be covered by BikePortland News Editor Michael Andersen. With his past experience as publisher of Portland Afoot Michael is the perfect person to cover this for us. He’ll help you understand why real estate development and housing issues have major implications for people who lead a low-car lifestyle. — Jonathan

—

For decades, Portlanders have been looking for bike-friendly, transit-accessible, walkable real estate to live, shop or work in.

Now, low-car real estate has finally come looking for us.

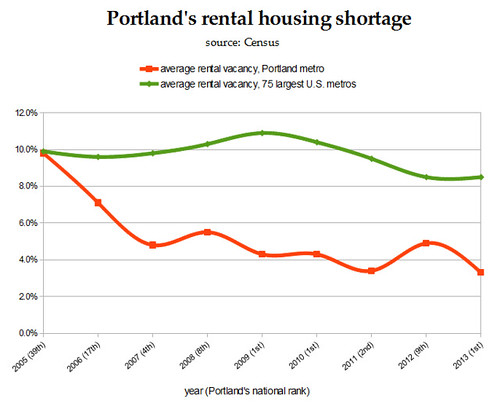

The evidence is all around. This year and next, dozens of new apartment buildings are rising in the central city without any on-site auto parking spaces, including the 118-unit Emery nearing completion in the South Waterfront and the 81-unit 37th Street Apartments on SE Division Street. These buildings are going up for a reason: Portland is fun, attractive and (compared to most of the United States) prosperous, all of which makes people want to move here, which has led to a deep and chronic shortage of rental housing.

By this spring, our rental vacancy rate was tied for the country’s lowest:

Housing shortages are hard to solve because housing takes up space, and space in a vibrant central city is expensive. But housing that doesn’t require on-site parking is far more space-efficient. In a way you can measure in dollars and cents — about $20,000 for every on-site auto parking space that a building doesn’t have to provide — low-car life is helping solve Portland’s housing problem.

Change is afoot in the world of commercial real estate, too. Portland’s booming set of talent-driven tech and marketing startups have become important tenants of local office buildings, and they’re looking for real estate that best fits happy, healthy workers who like to bike, walk, run or skate to work. Hard-nosed retail analysts are looking at the value per square foot of storefronts with good bike access and concluding that bikes can bring more customers to a store without increasing congestion or making the neighborhood less pleasant. The commercial real estate market is responding by embracing outdoor bike parking and making indoor parking and showers standard at the region’s best office buildings.

Bikes aren’t the only mode that matters here — they’re just one essential component of the world’s growing enthusiasm for urban life. Walk Score, the Seattle-based web startup that has worked itself into the heart of the U.S. real estate industry, just added Bike Score to its Walk Score and Transit Score ratings as a way to evaluate the attractiveness of a given address. Nelson/Nygaard, one of the country’s leading transit consulting firms, has begun consulting with private developers who want to understand low-parking housing projects. The City of Portland is aiming to quadruple the residential population of downtown over the next 20 years.

And all this change matters — because the most important thing behind most people’s choice of how to get from A to B isn’t politics, money or weather. It’s the location of Point A and the location of Point B.

Or, as someone else once put it: Location, location, location.

Portlanders’ location preferences are changing, and the city and country are noticing. This is the history we’ll be writing together with Real Estate Beat.

Some subjects you’ll see us cover here:

- the latest local apartment permits with low auto-parking ratios

- major new commercial buildings on bike and transit corridors

- amenities and prices at local bike-oriented apartments and condos

- ways low-car development does (and doesn’t) keep central-city housing affordable

- creative cohabitation strategies for Portlanders making the most of our existing stock of bikeable housing

- the surprising link between food cart pods and downtown office space

- in-depth interviews with the city’s smartest real estate professionals

Welcome to a story that is, in every sense, developing. If you know a real estate story that needs telling, get in touch.

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

I’d also like to see a focus on the housing justice movement, especially where it concerns people being priced out of their homes to make way for new ‘real estate’ developments. Livable streets shouldn’t be for people earning salaries alone.

How is restricting dense development going to help drive rent prices down? If you don’t increase the housing supply, prices will rise even more.

Who is restricting density? There are ethical means of rent control that can prevent gentrification. The problem is that city government is also in the real estate business, so preventing displacement of poorer communities isn’t part of their agenda.

You just spoke of residents “getting priced out of their homes to make way for new developments”. If we prevent developers from leveling single family houses to build multi-family apartments, isn’t that restricting supply? What methods are you talking about here?

So I guess we just let the free market destroy existing communities of color in the name of ‘progress’, just like Portland always has.

Cities change, get over it.

That’s a pretty dismissive way of looking at gentrification.

You’re just another white guy that moved to Portland. You’re part of the problem, not the solution.

I am not dismissive. I am realistic. And knowing that there really is no such thing as a “free market” – especially for housing (although it may act like it at times) – my goal is to use policy to manipulate the market into serving our interests while acting in it’s own best interests. There are not enough resources amongst nonprofits – and not enough will in government to socialize housing for a large enough chunk of the population – to build enough housing in areas that can support it to meet demand. We need to incentivize the private market to turn a profit serving a larger share of the population so that we can free up resources to better serve the share of the population that needs it most.

Resources are finite. Investors have resources to contribute. We should use those resources to meet our needs.

Rent control is the fastest way to keep developers from wanting to add to your housing supply. If you want the private market to keep your supply growing relative to demand, rent control is the opposite of what you want to do. You want to encourage investment, for profit. If you don’t keep your supply close enough to demand levels, rents increase. The key is keeping the supply ahead of the demand curve, and just write checks to landlords for low income residents, to help keep rent affordable.

Also, the entire point of zoning codes to most cities is to restrict density. Portland is only different in that they embrace density to a point (rather than tolerate it) for its benefits. We still very much limit density of development on every square inch of this city.

San Francisco and New York is proof that rent control, at least in its current form, does not work.

Nonsense. Rent control is the only reason there are still a lot of less wealthy people in NYC. Portland needs rent control and agressive regulation of our unsavory slum lords.

NYC is an outlier. You can’t honestly compare any other American city to New York.

Not nonsense.

From the 2nd footnote on the rent control Wikipedia entry (not controversial)

“If it is to have any effect, the rent level must be set at a rate below that which would otherwise have prevailed. (An enactment prohibiting apartment rents from exceeding, say, $100,000 per month would have no effect since no one would pay that amount in any case.) But if rents are established at less than their equilibrium levels, the quantity demanded will necessarily exceed the amount supplied, and rent control will lead to a shortage of dwelling spaces.”

Easy to explain, and the explanation is easy to find. Do any housing experts agree with you? Can you explain how rent control would help the housing Shortage? The correct answer is not “People who get them will pay less.”.

Ever try to find a rent controlled apartment in NYC? I hear it isn’t easy.

“If you want the private market to keep your supply growing relative to demand, rent control is the opposite of what you want to do.”

Why would you trust the private market regarding anything involving housing at this point? That’s absurd.

Yes, yes, cynicism is a fantastic contribution to a genuine policy debate.

We know that private investors want to earn a profit. So you enact policies that make social justice profitable. If you have a housing shortage, you enact policies that make it profitable to build housing to address the segment of the market that is undersupplied.

If you fail to utilize private market to accomplish your policy objectives, then it’s up to taxpayers to address the market’s inability to do so with, in this case, government-owned housing, which nobody wants to live in or near to.

By requiring housing to be more expensive to construct (e.g., requiring parking or capping the number of dwelling units), you make it a less attractive investment, so less will be built. Instead, investors will try to maximize their profit by, for example, building higher-end dwellings whose buyers/tenants will more likely be able to absorb the cost of the construction in their unit. Since that market is presently saturated, investment in multifamily housing construction will stagnate.

If you make it profitable to build multi-family dwellings that can rent for $700/mo, then developers will do so. Under the present regulatory system, that would NOT be profitable, so you don’t see it happening.

Shorter me:

If you want to keep rents low, keep your supply adequate to meet your demand.

If you don’t want to let the private market address the supply shortage, then by definition, government must.

If you don’t want the private market or the government to address the supply shortage, demand will continue to rise anyway, the supply will be thusly constrained and rents will rise, forcing current tenants out to less expensive areas (this is gentrification, too).

The key is to enact policies that make it profitable to increase the housing supply in areas of the city where it can be supported.

Or, even shorter, use developers’ greed as a means to accomplishing your housing goals.

You’re presenting a false dichotomy; that the only two options are markets or government. You’re forgetting that communities have much power to control their own direction and planning when they organize. That’s sadly something lacking here in Portland, though there are several new groups building up a base of supporters to counter the growth machine that’s started taking over. Surely a lack of housing is of concern, but how and where and how big we build needs to be up to the people who already live here, not banks and corporate developers.

But communities need government to give their power any teeth. Communities groups aren’t involved with zoning, but neighborhood associations all have land use committees that are in contact with the city government.

The city needs to add to its housing stock to make room for future residents. If we don’t, those future residents will push out existing residents.

Therefore, somebody needs to be building housing, somewhere, at a pace that matches demand. Who is going to do this? Communities? Taxpayers? Or private investors?

We elect city leaders to make choices for us based on data. Some areas will change. We can either target that change or let it target us, because it’s coming, and the only thing you can do to stop it is to make your city an undesirable place to be.

How is the city going to quadruple the number of residents downtown when they enact minimum parking ordinances?

http://www.oregonlive.com/front-porch/index.ssf/2013/04/porland_city_council_approves.html

There is no room to widen the streets for additional cars. Where will all of these stored cars go when they need to drive somewhere?

Look at what San Francisco does. I lived there for 6-years, and quit vehicle ownership when I lived there. Many residents of that city live very comfortably and sustainably without cars.

Those minimums don’t apply downtown. The central city plan district, which is more than just downtown, still has no parking minimums.

There is a ~250 unit, 14-story market-rate rental housing building proposed for SW Jefferson between 11th & 12th. (The public notice in the window of the “field work” space has an incorrect height.) There will be 90-something parking spaces in 2 underground parking levels. On the block bounded by SW Clay, Market, 11th, and 12th there are two buildings proposed for PSU student rentals, one 8 stories on the SE corner and the other 5 stories on the NW corner. (I could be off on those building heights and I know nothing about the designs, including any parking, but I would expect it to be minimal given the proximity to PSU, streetcar, etc.)

There is also a 1/2 block lot being cleared between SW Jefferson & Columbia on 2nd. The owners are expecting a 25-30 story building there, probably mixed use like the KOIN Tower nearby, but there are no announced plans at this time.

Thanks for the tips! Keep ’em coming.

I should add that the property on SW Jefferson had, about a year ago, been the proposed site for a ~300 unit, 20-story building with zero on-site parking. The idea was for a luxury apartment building for “wealthy foreign PSU students”, almost all of whom arrive without cars. The developer claimed to have market research showing that the demand existed, but many in the neighborhood were skeptical. There was concern about what would happen to the building if that research was wrong.

There is more information about the proposed 8 story building at 11th & Market here:

http://efiles.portlandoregon.gov/webdrawer/webdrawer.dll/webdrawer/rec/5893804/view/

Thanks for covering this topic. Hopefully people (namely, Amanda Fritz) will realize that a substantial population in portland exists that does not want to have a mandatory auto parking spot at their their apartment for a vehicle they do not own. But I’m a little weary of the new apartments that use biking as a marketing gimmick in a patronizing way. Naming a building after a Trek Milano and using a bicycle logo and hanging a few bike racks in a storage room isn’t really accomplishing anything very groundbreaking.

Induced demand – if you build a wider road to alleviate traffic congestion, the greater capacity just attracts more traffic. The same thing happens with parking. What are we planning to do with all the cars that Amanda Fritz and the rest of city council mandates that we add to inner Portland? Thankfully, we seem to have grown past the idea of road widening. We’ve even said no to widening I-5 into Washington. So, it looks like even more traffic and longer commutes during rush hour. Unfortunately, this affects everyone, not just auto drivers. Bikes,busses and streetcars suffer greatly in traffic congestion.

Trek Milano? Not possibly, the fashion mecca in Italy (where bikes are kind of popular)?

My bad. Its a Bianchi Milano, not Trek. A previous article stated that it was named after the architect’s bike.

How about a Mint Milano?

Gentrification in Portland will be here as long as the Urban Growth Boundary exists here (it was kind of invented here). In the 20+ years I’ve lived here it’s happened quickly in Sellwood, NW/Nob Hill, Pearl, LLoyd, Alberta, Mississippi. Happening currently but at a slower pace in St. Johns and Kenton (mostly spill over from Mississippi and Alberta there), Cully. And I’m seeing the starting of it in Montavilla, Foster/Powell, and somewhat even in Lents. And I have no doubt that in the next 10 years or so it’ll start spilling over the 205 into Gateway/205, Parkrose, down Halsey,Glisan, Division, and Powell.

It is the intended consequence of the UGB to do this. Which though it sucks if you’re poor (and believe me I’m by no means rich – I am the 50ish%) it does keep the city on a whole updated and clean. It also keeps suburban sprawl to a minimum which is also good. One need not look too far to see how most cities in the US are with rotted cores and all the “action” in the burbs.

And though the effects of gentrification are both good and bad I really believe that there is more good about it than bad. And like in all things you can’t have it all.

I think we need to recognize the difference between “revitalization” and “gentrification” … The former is good, and is what you’re talking about: new businesses, improved buildings, improved housing, better places. The latter involves displacement of existing communities, and many consider it to be a travesty.

To a certain degree market forces keep gentrification closely intertwined with revitalization. But there are methods to try and create more just, equal places. Building more, denser housing can help, but I’m not sure if the too expensive, market rate micro housing often praised here is the answer.

Being poor shouldn’t mean you have to live in a shitty place. We can create good places where diverse groups interact.

“Micro-housing” is not the answer.

There are some people for whom that may be the answer, but it is not a mainstream solution.

There is a major imbalance in the type of housing people want, and the type of housing available. Due to the dearth of supply for the type of housing people want, you see rents rise faster (sometimes much faster) than inflation for those dwellings. As a result, many people are forced into non-ideal housing options because the supply of ideal housing is so constrained.

We need to enact policies that make it profitable to increase the supply of housing across the entire spectrum of housing types that people want. That would include some micro-housing, some boarding houses, some single-room occupancy, but must also include larger dwellings for families so that they too can afford to live a low-car lifestyle.

The houses are there, they just might not be in the “ideal” neighborhood for many. Increasing public transportation and the continued work of neighborhood improvement will help alleviate this. More people will realize that they don’t have to live in Buckman, and that Lents or MontaVilla will be good places to live.

Part of the problem is that too many people aren’t will to just compromise and live a little further out. And frankly too many people in this town have a really warped sense of distance (like how houses that are 5 miles from downtown are just so far away…)

People with the means to do so will pay rents they deem fair to live somewhere they desire. It will always be this way. If we increase the supply where demand is high it will alleviate pressure on other areas of the city to contribute. If we don’t target density, it will spread more uniformly without respect to available services and we will risk losing the character of all neighborhoods, not just the desirable ones. This is more than just psychological, it’s important to have a variety of housing stock to meet the needs of your citizens, present and future.

True, but many would argue that increasing density will also change the character of neighborhoods. (i.e. taking a neighborhood that was predominately made up of single family homes and jamming a bunch of small rental apartments into it, is going to drastically change the neighborhood)

And service requirements change with a changing city. That’s not a good enough excuse to ram through any density increase.

I’m basically just saying that more people have to be realistic and possibly change their “ideal” housing situation. Portland is unique in that it is by far the cheapest city on the west coast to buy a house (and I’m not talking about $400k houses, I’m talking about people who can buy a house in Lents for under $100k).

Are you saying that more people want small apartments with no parking? (I didn’t think so as you just stated that micro-housing was not the answer)

We have an overabundance of single family houses. We need a diverse mix of housing types to address the wants and needs of today’s – and tomorrow’s – housing market. Presently people who would prefer apartments are renting or buying single family houses because that’s what we have the most of, and apartments are heavily competed for. Many times this means renting a SFH with roommates even if you’d prefer to live alone. This creates competition for people who do want single family houses, raising the price of renting or buying their preferred housing type, and perhaps driving them into the suburbs, where they’re more likely to need a car which will create a hardship when that shouldn’t be necessary.

If we build more apartments where the density is supported by infrastructure & services, we can add to our housing stock, diversify our housing stock, forego expensive infrastructure upgrades to support the new dwellings, and preserve our stock of single family homes and neighborhoods for people who want that housing type.

Do you not agree though, that changing neighborhoods which you say are predominantly single family houses to apartments will change the character of the neighborhood? Many neighborhoods in Portland are the way they are because of their housing make up.

I do agree that we want to preserve a lot of the single family housing stock. That’s why we need to allow very intense development of transit corridors. We need to give up a lot in certain places so we can preserve a lot elsewhere. If we fight intense development where it fits best, we will push development into the neighborhoods where people really don’t want it. We have to pick our battles because we can’t have it both ways, the development has to go somewhere. Intense development along transit corridors should be encouraged specifically so that we can preserve the housing stock and character of the existing neighborhoods.

The point is not to replace neighborhoods of houses with neighborhoods of apartments, it’s to line transit corridors with apartments and retail. This will increase and diversify the housing supply, bring jobs, services and retail closer to neighborhoods of predominantly single family houses without threatening them, and create more demand for transit, justifying improvements in transit service and amenities, as well as pedestrian and cycling infrastructure.

I think that you’re discounting the fact that MANY people in shared houses do so for the lower prices in rent, not necessarily just because there aren’t enough options. The key is that there aren’t enough dirt cheap apartment options (as there probably shouldn’t and won’t be in a desirable inner neighborhood). If some of these shared rental houses are replaced with apartments that rent for $800-1200 month, I don’t think many of the folks that are used to paying $250-500 would be psyched to move.

I’m curious where you get the idea that we have an abundance of single family houses. I just bought a house and I’m amazed I even found a house to buy and won a bid. The first one we bid on had 10 offers. Yes, I see some new houses being built, but they seem to be above $350K. (I was lucky and got something under $300K, only 1/2 hour ride from downtown.) Yet I see apartments being built all along MLK, and Williams/Vancouver. In other words, I see more apartments being built than houses.

@Paul Cone:

The pool of housing available to somebody who needs a mortgage to buy is a subset of the actual stock of housing for sale. Many rules (sometimes laws, sometimes arbitrary bank rules) often prohibit or discourage banks from lending for anything other than a single family home in great condition. When buying a home, you can only truly consider buying from the pool of housing that is available to you. As long as lending rules reduce the pool of housing available to a buyer, it will distort the market in favor of that pool of housing. It is not reflective of what people might actually want in an unfettered market. This distortion creates an artificially larger pool of buyers for an artificially reduced inventory of housing. It also increases the sale price for housing stock in the pool of saleable inventory which makes sellers happy, creates an incentive for people to sell who might not otherwise, and thusly gives the appearance of a healthy housing market, whether or not that’s really the case. Lastly, there simply isn’t enough housing available in Portland to meet demand, period, so any available housing is in demand.

By increasing the pool of housing that is not single family housing, you’ll reduce demand for the pool of housing that is single family housing. Plus, our land supply is so constrained that there simply isn’t room for much new single family housing, so you won’t see much new single family housing construction as a total share of new residential construction. Again, the argument is for single family housing to be a smaller share of overall housing, not to remove large quantities of single family houses from inventory. Some will need to be replaced with apartments, but by limiting that to transit corridors we preserve the stock deeper in neighborhoods.

@davemess:

I posit that a larger pool of new $800-1200 apartments would reduce the rents on older apartments that could bring those within reach of the shared housing renter’s comfort level in many cases. Throughout my 20s I was competing with families for renting single family houses, and I would’ve preferred living in an apartment for double what I paid to live with roommates. That still wasn’t enough to get an apartment in the city. Rents on older buildings don’t need to pay off construction loans, so there is a lower revenue floor that will still net a profit for the owner. Presently older buildings are pulling big rents because of the supply constraint. By building more dwellings in the 8-12 range, older building owners can still turn a profit while targeting a different segment of the market, it just won’t be as big a profit as they’re earning right now. But profits are merely an incentive for investors to provide housing, the important thing is that we have enough housing to meet demand.

@Joseph, I think you are saying that we have an overabundance of single family houses vs. other types of houses? I certainly ran into the problem of banks not wanting to loan for anything but the house in perfect condition. Also, the house we lost the bid on went for significantly less than our offer, but I’m almost certain the winning offer was cash. There is a lot of cash out there, creating even more demand and driving up prices.

Joseph, you honestly think landlords will reduce rents? So in essence you’re looking to flood the market into the opposite direction that we’re currently in (i.e. you want to have a high vacancy rate)? The amount of housing it would take to achieve this would be pretty immense. I still don’t necessarily agree that the rents in older buildings would then drop to a level where the people currently renting shared houses would move into them. It’s an interesting idea though.

Paul, I agree the market is crazy competitive right now, but there are plenty of houses well under $300k within a 30 min. ride of downtown. I’m about a 30 min ride (I guess I ride kind of fast compared to the average person), but my neighborhood averages $110-175k houses (Just had friends buy a place in Lents for $100k). It’s just about the desirability of the neighborhood, not necessarily just the proximity to downtown.

Glad you found a place though.

@davemess: Yes, landlords will reduce rent if that’s what it takes to keep bringing in tenants. A room that makes less profit than last year is better than a room that makes none at all. As a social justice initiative, we should reduce the incentive for landlords to bring in new tenants at the expense of existing tenants. When rents rise faster than inflation, people are forced out of their homes when they’d prefer to stay and can afford the existing rent, or, for members of the workforce, when they could probably deal with annualized increases at the rate of inflation. This isn’t fair. A goal of the citizenry should be to ensure the supply of housing is such that average rents increase at no more than the rate of inflation, and find a way to help fixed-income citizens stay in place. This may involve some rent control or directly subsidizing rent for certain citizens (I prefer the latter).

Rather than flood the supply, I’d prefer to set vacancy rate targets that would be low enough to ensure that existing tenants have a fair shot at keeping their homes but high enough that rental properties are still a worthwhile investment.

The dual-pronged goal is vacancy rate targets and average rent targets, likely indexed to a formula including city income and inflation rates.

@Paul Cone: Yes, I always use too many words but that’s a correct read on my comment. Through many complicated mechanisms, the available inventory is artificially reduced for the vast majority of buyers, so it creates an artificially high level of demand for whatever is included in that “available” inventory. Then builders build more of what is “in demand” so you get more of that same type of inventory. This has been going on for a couple generations now, so that’s why there is so much monotony in the housing stock.

And you’re right, there is a lot of cash out there competing with conventional mortgage buyers which further increases prices for the “available” supply. Normally cash buyers would do so to improve a less than perfect house to sell (one that wouldn’t be available to a buyer who needs a mortgage until they fix it up), now it’s often to rent it out because the rental market is so tight – and profitable. So the rental crisis can impact homebuyers too, by removing from available inventory viable homes for use as rentals, restricting the supply and driving up prices.

when the city lacks the backbone to resist the vocal motorists complaining about parking-free apartments then progress comes to a halt… they enjoy THEIR free parking too much to share, and like many issues that people shouldn’t be allowed to vote on they will likely band together to slow the progress of car-free living…

Thanks for doing this, Michael and Jonathan. No one is better placed than you and BikePortland to develop a strong counter-narrative on this issue. I’m tired of hearing that there’s “no market” for smaller housing with less parking. I look forward to trying to change some minds by pointing them to articles here.

Developers and investors getting rich off of greenwashed schemes that hurt the poor, gentrify, and are weak “solutions” for environmental crises. But the privileged liberal bubble gets to go a few decades longer without bursting. “Density” is the mantra of the privileged. Notably absent are any social justice concerns.

Get outta here with that “we’re doing it for the poor” crap. I’ll believe people are serious about density if Irvington and Eastmoreland go first.

If we were really doing it for the poor, you’d see policies that incentivize developers to build dense housing near transit that is basic enough in design to build inexpensively and turn a profit from rents that could be afforded – without direct subsidy – by families in lower-income brackets.

With current policies, it’s really only profitable to build luxury housing, so that’s what we’ve seen the most of. Since the luxury market dried up (years ago), you saw developers start to address non-luxury market-rate housing. Then we turned around and sent them a very clear message earlier this year that we want to disincentivize that sort of thing, so now it’s only profitable to build very small complexes (to get around parking requirements) or luxury housing (which is still saturated). Small complexes alone will not meet housing demand, so we will continue to see increasingly anemic multifamily investment combined with rents rising faster than inflation, pricing families and lower-income residents out of their homes.

Which is great if you’re a landlord or an investor whose investment was already built.

I think a lot of people are confusing cause and effect re: gentrification and development. People see a lot of new development in a gentrifying area, and rents rising, and assume that the new development is causing the rents to rise. The relationship is probably mostly in the reverse direction – rents are rising because an area is popular, so it becomes profitable to build new apartments in that area (because you can charge higher rents and rent units faster).

On the contrary, the new apartments actually slow down the rise in rents because they increase the supply of housing. Even if they are at the high end for the area, they attract renters who would have competed for the existing mid-end options in the area, so then the mid-end landlords have to lower prices (or not raise them as much) to attract tenants.

*Complexities include: if the home you’re renting is demolished for new development, you have a legitimate beef. Not one that justifies never having new development ever, but a legitimate beef.

*Also, if an eyesore is demolished and replaced with a shiny new complex that may cause an increase in rents in that immediate block or two.

*Gentrificaton ITSELF (even without new development) does increase rents and push lower-income people out of existing communities. But gentrification and new development are not the same thing and need separate public policies to address them.

*I’m sure there are more complexities but more housing units mean rents overall go up less than they would have otherwise.

“But gentrification and new development are not the same thing and need separate public policies to address them.”

Precisely, there are ways to address housing shortages and displacement at the same time. We don’t have to pick one or the other.

We cannot, however, keep rents in check without increasing the supply to keep pace with demand.

Nobody’s arguing against increasing the ‘supply’ of housing. Seems like you’re deliberately missing the real concerns here. I’d recommend reading Paul L. Knox’s ‘Metroburbia USA’ and David Harvey’s ‘Rebel Cities’ if you’re interested in learning where I’m coming from. If not, keep on reading Money magazine or whatever it is that’s taught you to worship capitalism.

But you have already read them. Maybe you could provide a compelling bullet point or two about the “real concerns” you learned about after reading the books?

Seems like a deflection to avoid discussion as it stands. You don’t seem to be making a very good case on your own for your cause, so it’s just “Go read this book, money worshiper, I have no more points to make, myself.” You suggested rent control, but then didn’t really defend the idea.

Your comments remind me of old anarchist “truths” about how business and govt are inherently bad for people. Since pre-govt societies have endured much higher homicide rates, (well documented by S Pinker) I am skeptical!

It strikes me that we both basically want roughly the same end result but have different ideas about how to arrive there. That doesn’t make us enemies, yet you seem very eager to lump me into a category in which I really do not fit.

The problem is that we have a housing crisis in not only Portland, but the entire metro region, and it’s a crisis now. We’re in the top one or two for tightest residential and commercial rental markets in the country – landlords are already getting their way and people in existing apartments are seeing their rent jacked up by sometimes $100s a month each year/lease renewal. People are being priced out of their existing homes right now, even with the current pace of construction.

We don’t have time to wait. We don’t have that luxury right now. We certainly don’t have time for a paradigm shift in government or the housing markets. Great long term goal, but we need solutions on the ground, yesterday.

Given the rules we have to play by right now, I’ve staked out my position and I believe it’s the quickest way to stop the hemorrhaging responsibly.

I welcome your suggestions. This is a very serious matter.

How about giving us a synopsis of these books?

The problem with your stance, and others stances like it, is they simply criticize without giving any viable solutions.

That’s what you are: someone who critiques without giving any ideas. It’s all about the “system being corrupt” and “victims” and “justice” and other emotional charged, hyperbolic language. It’s pure obfuscation of the situation at hand.

And then when you and people aligned with your ideology try to explain it, we’re accused of not understanding and we’re berated that we just don’t get it and we’re intellectually inferior.

Do you know why people understand capitalism and their various forms? People understand it. I have no idea what you’re talking about because I have to cut through the quixotic fluff.

If things need to be corrected at the “free-market” level, that is what government is for whether it’s through tax incentives, subsidies, or zoning. Currently, we do both, and Portland is rather sensitive to housing issues and we probably do better than any American city there is.

Go ahead and bash the Pearl, but it does have its fair share of housing where there are income maximums people can have, right next door to expensive condos.

So you came back to the discussion to ad hominem Bloomberg, but no thoughtful response to these thoughtful folks? (Excluding myself)

Bummer!

Sure we can: public housing and rent control.

You’d just push demand to the other side of the boundary where rent control applied, or you’d have to increase the supply of public housing at the rate of demand. Either way, you haven’t really solved the suite of problems that need to be solved by land use choices over the next generation. The public debt involved with increasing the supply of public housing to meet demand over the next twenty years would be crippling or impossible to secure under the present state property tax laws.

Most of the low or no car new buildings are going up in already expensive neighborhoods, how is this “hurting” the poor. If anything I would think it is freeing up moderate-low tier housing in other parts of the city that these folks would have moved into.

I don’t think anyone is claiming they’re “doing it for the poor”. At the same time I don’t think they’re “sticking it to the poor” either. Doesn’t have to be one or the other.

> the most important thing behind most people’s choice of how to get from A to B isn’t politics, money or weather. It’s the location of Point A and the location of Point B.

Exactly. I hope that Portland, with its fairly bike friendly street grid and vibrant neighborhoods, can absorb the greatest majority of new people moving to the area because if Portland doesn’t, car-centric suburbia will.

The greater the population Portland can capture (and get walking, biking, and busing), the better we as advocates can push for regional funding of active transportation investments (compared to, say, the tens of millions Hillsboro is spending on widening Hwy 26, which counteracts much of our work by encouraging Portlanders to drive to Intel rather than take the max).

I’d also be interested in seeing coverage of policies that prevent small scale but wide spread increases in density (i.e. ADUs, tiny houses, etc).

This is an great read related to parking and housing:

http://daily.sightline.org/2013/06/05/whats-in-your-garage/

Great idea, Peter.

“Cities change, deal with it.”

Wasn’t that Robert Moses?

Bloomberg re: high line

Bloomberg is a joke.

Hart Noecker said…

“You’re presenting a false dichotomy; that the only two options are markets or government.”

I mean, that would be a false dichotomy if that were what he were doing, but that’s not actually what I’m seeing Joseph argue. He’s talking about using government to shape the environment in which the market works via incentives. And that’s a vision which doesn’t preclude the input of an active, organized community, either.

Allowing for input is only the illusion of community control. This neoliberal view of building cities for the most profit is a soulless enterprise, and victimizes thousands in the process. City hall is in the real estate game, that’s for sure. And that’s something that needs changing.

I like everything you said.

Thank you. This is a very important issue to me. I’ve given it a lot of thought. I just need to coalesce a like-minded group to help pursue change where it is needed to support these concepts.

I’ve been following along. I think this article from Washington DC hits many of the same points. http://greatergreaterwashington.org/post/19662/raise-the-height-limit-thats-part-of-a-bigger-question