doors is the nerve center for America’s premier

bikeshare system.

(Photos © J. Maus/BikePortland)

An unassuming warehouse in the industrial Navy Yards neighborhood of southeast Washington DC is the headquarters of America’s most successful and largest bikeshare system.

I’ve been using Capital Bikeshare for a week now and it’s fantastic. With Portland set to launch a similar system next year (hopefully), I wanted to find out what makes the system tick. So on Thursday I rented a bike from a station two blocks from where I was staying and pedaled toward the warehouse. I was met by Capital Bikeshare General Manager Eric Gilliland.

When Capital Bikeshare launched in September 2010, it had 49 stations and 400 bikes. Today, Gilliland and his staff oversee 199 stations and 1,700 bikes that span throughout the DC region. (For context, Portland is aiming for 75 stations and 750 bikes and New York City is expected to launch in May with a whopping 600 stations and 10,000 bikes.)

The bikes and their stations have become a fixture on the streets of DC. They are part of the cityscape much like bus stops, taxis, or newsstands:

made possible by:

- Planet Bike

- Pro Photo Supply

- Readers like you!

As former executive director of a local bike advocacy group, the Washington Area Bicyclist Association (WABA), Gilliland is no stranger to working around bikes. In many ways, his mission at WABA is similar to his task at Capital Bikeshare: Get more people on bikes. And Capital Bikeshare has done just that. Since 2010, the system has served 3.6 million rides, it now boasts over 20,000 members and it’s only public transit system in the U.S. that pays 100% of its operating costs through user fees (TriMet’s “farebox recovery” rate is just 25%). Key to the system’s success are DC’s many tourists, whom Gilliland says are “big revenue generators” because they tend to ride longer and don’t mind paying the extra fees (trips under 30 minutes are free).

Unlike the forthcoming CitiBike system in New York City (which Citibank has sponsored to the tune of $41 million) and Portland Bike Share (still dreaming for a big sponsor) which are 100% privately funded, Capital Bikeshare is funded by federal grants and local governments.

When asked about funding models, Gilliland sees more a hybrid funding scheme as the best option. “We’re the opposite of New York City, but I think a middle ground would be good,” he said, “There’s a role for private funding, but it’s a transit system, so DOTs should play a role. It’s a public good you’re providing — it’s an investment in your city.”

The next step for Capital Bikeshare, Gilliland said, is to sell naming rights to a private sponsor (as evidenced by the image below which shows how the new front racks (on the left) have a spot for a sponsor’s advertisement):

While sponsorships and size tend to dominate the public dialogue around bike share, on Thursday I got to see the other side: the warehouse and workshop where a team of hard-working staff keeps the system up and running.

Capital Bikeshare employs 45 people; a mix of managers, mechanics, technicians and a street team (technically they’re all employed by Alta Bicycle Share, the system’s operator).

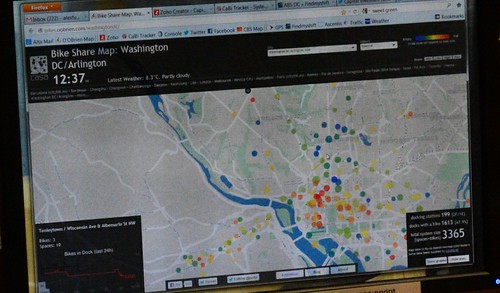

Most of the staff at Capital Bikeshare is made up of what are known as “rebalancers.” They’re in charge of making sure there are just the right number of bikes at any one of the stations at any given time. The term “rebalance” is used because they attempt to balance out the empty and full stations so users are assured either a bike to rent or a place to dock no matter where or when they need one.

Unlike a subway or bus system, where the passenger vehicles rotate through the routes consistently, there’s a finite number of vehicles in a bikeshare system and a limited number of places to park them (each bike must be secured at an electronic docking station). And depending on topography, commute patterns, and special events — mass migrations of the bicycles from one part of town to another presents a challenge. The northwest part of DC, for example, is densely populated and it’s on a hill. This means in the morning, thousands of people grab bikeshare bikes and roll into downtown.

“In the morning, we try to have [downtown] stations empty,” explained Gilliland, “As they fill up, we sweep up the bikes and try to catch another wave of commuters.”

Big events like July 4th and sunny spring and summer days also put pressure on the rebalancing crew. On Saturday, as temps neared 60 degrees, 455 bikes were being used simultaneously. During a typical day, about 200 bikes will be out at any one time. The number of daily trips taken also varies greatly depending on the season and events. According to Gilliland, the system serves about 5,000 trips per day, with that number rising to 8,000 in peak season. They expect the first 10,000 trip day this summer.

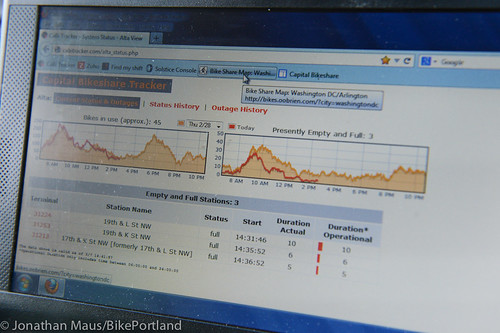

Tracking how many bikes are available at any given station falls on the shoulders of Rebalancing Supervisor Alex Fuentes. At the 2nd Street headquarters on Thursday, Fuentes sat at a desk monitoring two computer screens. Staring at an online map that shows station locations and the number of bikes available, Fuentes held a dispatch phone in one hand and a computer mouse in the other. As the evening commute ramped up, he wanted to make sure there were enough bikes and enough empty spaces so customers wouldn’t run into any delays.

Rebalancing is important not just for customer service, but I learned Thursday that Capital Bikeshare’s operating contract with the District Department of Transportation stipulates they can be fined if any station is empty or full for more than an hour.

After staring at the computers intently, Fuentes picked up the dispatch phone and gave orders to one of his truck drivers: “Go to 17th, pick up five bikes. 18th and Penn pick up fives bikes. Go to 19th and L and drop off five bikes.”

Fuentes also manages the five Capital Bikeshare service trucks. The white Freightliner Sprinter trucks are operated on two shifts per day (leaving only a few hours when there aren’t staff on the streets).

Avoiding fines and keeping users happy falls on the shoulder of rebalancers like Javier Griffiths and Veltrick Copeland. After rolling a few bikes up the rear ramp of his truck, Griffiths, wearing a reflective vest with Capital Bikeshare emblazoned on the back, hopped into the cab, flipped open a laptop and headed out on a service call. I sat in the passenger seat as we rolled out to pick up bikes from two stations near Union Station.

“It’s a fun job,” he said, as we rolled out of the warehouse yard. “Sometimes I’ll see people at a full station with no place to park and they’ll get all excited when they see the truck pull up.” Like many people that work at Capital Bikeshare, Griffiths believes in bikes. A former bike messenger who grew up in DC. and sometimes takes bikeshare to work, he spoke of their many virtues: “Biking is usually the fastest way around town. You don’t have to worry about parking… I just love bikes. They’re the future.”

Capital Bikeshare’s contracts with the various jurisdictions they operate in requires bikes to be available, and it also requires that the bikes stay in good, working condition (technically, the contract says each bike in the system must be “touched” by an employee once per month). That job primarily falls to the six full-time mechanics on the staff. I watched one of them, Timur Mukhodinov, do an annual maintenance service. He replaced nearly all the main components; lights, tires, rack, fenders, kickstand, bell, and so on.

Across the warehouse from the mechanics’ workshop, Bike Checking Street Team Manager Taylor Jones, Deputy Operations Manger Mike Garrett and Technology Manager Ralph Lucas discussed an issue in the Station Service office.

Similar to the rebalancing and mechanic crews, Capital Bikeshare is contractually obligated to keep the stations fully operable or they’ll be fined. The contract mandates that each station in the system is checked up on at least twice a month.

During my week of using the system, I never had a beat-up bike. And despite a sunny Saturday, I never had to wait or ride to a new station to rent or park a bike. It seems that, even in their infancy and with constant expansion plans, Capital Bikeshare is doing a great job managing this system. So much so that Gilliland and his crew have been sought out for their expertise. “We’ve sort of become a training academy for other cities. We had some folks from New York City in here last week.” said Gilliland.

It’s somewhat ironic that Gilliland, who once led a non-profit bike advocacy group, now oversees operations of a private company that might have even greater influence overy transportation policy in his city. The thousands of daily bikeshare users are also riding in bikeways that Gilliland helped push the city to build. And now Capital Bikeshare is doing the pushing. “All the people out riding on the bikes is forcing the City to do a better job,” explained Gilliland. “Overall, it’s been an amazing success.”

- 45 people on staff

- 61 reported crashes

- 8,900 trips in one day (the record)

- 3.6 million rides since September 2010

- 25 bikes stolen

- 11 stolen bikes recovered

- 14 bikes lost

- 10 bikes have had “extreme vandalism”

- 6 full time mechanics

- 25 rebalancers

Thanks for reading.

BikePortland has served this community with independent community journalism since 2005. We rely on subscriptions from readers like you to survive. Your financial support is vital in keeping this valuable resource alive and well.

Please subscribe today to strengthen and expand our work.

Great insight into the nitty gritty of running a bike share system. Let’s hope Portland can run it half as well as DC.

Thanks for this great behind-the-scenes look. That’s been missing from everything else I’ve read about bike share. Interesting to see the stats include “61 reported crashes.” Any idea how many serious injuries? any deaths?

No fatalities. Not sure about injuries, but since I can’t recall anything super-serious, it seems unlikely. .00017% non-fatal accident rate FTW.

Er… .0017%. I can do the division, but counting zeros can be too much.

Interestingly, none of the serious injuries have been head injuries — despite the low rate of helmet use observed by several studies.

@Steven/9watts: Everyone agrees that it would be great to cut the fossil fuel use. I was part of a team that surveyed eight bike share operations around the world; only one (Denver) used bike trailers to rebalance up to four bikes, and only in one neighborhood. Given the distances between stations here, the 48 lb. weight of the bikes, and wage rates (proposed minimum of $10/hr), Alta has apparently not determined that it’s feasible.

@Dennis: That’s been done at many locations, and dozens of new stations have been added near high-demand locations. However, demand will probably always exceed supply for peak-hour, peak-direction trips.

Payton,

thanks for your thoughtful reply. I’d love to know more.

“Everyone agrees that it would be great to cut the fossil fuel use.”

“Alta has apparently not determined that it’s feasible.”

I wonder if there’s some way to see those numbers. I’m not doubting their conclusion at all, but wonder

(a) at what prices (of fuel, insurance, employee health benefits, etc., vehicle maintenance) does the extra cost of using bikes and trailers to rebalance the fleet disappear? Or, put another way,

(b) what change to the fee structure would make it work now, at current (fuel) prices?

I’m (obviously) not Alta, but the way I look at this question is not ‘it would be great’ but ‘what will it take’?

Thanks for what you do and the inspiring behind the scenes look you granted Jonathan.

Ask (google) and ye shall receive (information).

http://tinyurl.com/rebalancing-by-bike

fascinating report. I learned a lot.

I think it is nifty that you incentivize members to return/rebalance the fleet themselves. That certainly has always been my impression of how rentals of other types of vehicles do it (or rather they charge extra if you don’t). But do you know/are you at liberty to divulge how much extra it costs the system if a person doesn’t return the bike to where they got it? or participate in whatever rebalancing algorithm you have worked out for the system? I can think of a bunch of ways to offer members discounts, incentives, or whatever to take a bike uphill/counterflow/or whatever the local term is. Not that I don’t think it’s great to hire folks to do the rebalancing but if that means you need a fleet of Sprinter vans then other (crowd-sourced?) options start to seem more viable.

We are so excited to get Bike Share in NYC (Citibike) this May. I have an annual pass in DC because I go there a lot and love the system. Have also used it in Montreal. Every great city deserves a Bike Share program. There is no better solution for short inner city travel than a bike you can pick up and drop off easily. I wasn’t aware of all the re-balancing. It saddens me a little to know we have to use fossil fuels to move the bikes around. How about getting humans to ride the bikes for re-balancing (in other words, hire local unemployed youth to ride the bikes from station to station to perform the re-balancing. Just an idea for one less truck on the road. Keep up the good work.

Velib gives riders time credit for returning bikes to less popular stations. There’s still a ton of rebalancing that has to go on via flatbed truck, but the credit system probably cuts into it a little.

Capital Bikeshare had a promo at least for a while that gave you credit for riding from certain stations that get too many bikes to other stations without enough bikes.

The real help has been the increasing number of stations–it makes it more convenient to park exactly where you’re going, and it allows for alternatives if your station is full.

Super interesting article. Thanks, Jonathan.

Two things I didn’t understand:

(1) “can be fined if any station is empty or full for more than an hour”

fined for a station being full? Please explain.

(2) the rebalancing seems like a perfect task for a bike and trailer. Any particular reason that wasn’t chosen? I’d think it could even pencil out financially if you figure what that Sprinter van cost. More money stays local and the message that bikes are/could be a full substitute would be even more powerful than it is now.

If the station is full, nobody can drop a bike off.

Got it – thanks.

The problem with full stations: every dock has a bike in it, so there’s no place at that site to drop off the bike checked out to you. If the station is a block from your office, you may be forced to turn in your bike at a station 2 or 3 blocks away & not get to work on time. Meanwhile the meter’s running . . .

Really cool to see how the system works in DC.

Why so many fines? To some extent I understand that it’s an incentive to keep things moving smoothly and it seems to be working… and I don’t have any better ideas, but it just seems odd. Is that really the best idea they could come up with?

Standard performance measure to make sure the private company does their job.

Since the bike racks are mounted on a platform that is portable, it seems that a way to cut down on re-balancing would be to put out more racks where there is higher demand.

I really appreciate the effort you make to go in and explain things well. I’ve got new-found appreciation for the work that goes into operating the bike-share system as well. I don’t like how it feels though that all these East-Coast squares are doing stuff with bikes that we’ve never done before! I’m used to the smug Portland certainty that we were years ahead of the curve.

Not mentioned in the article is Eric Gilliland’s background as a bike messenger in D.C. He also worked on Capitol Hill and for several law firms…all useful experience for his current job!

Great article and photos! We DC squares love our “CaBi” and are pretty excited to be ahead of Portlandia and the rest of the country in bikesharing. But at the end of the day we’re all on the same team. A rising tide raises all boats, or something.