This is a guest post from former news editor Michael Andersen.

The top executive of Portland’s mass transit agency said this week that the Portland region has four top transportation priorities, and three of them are to expand capacity of urban freeways.

“These are projects we’ve known we need to do for some time,” Neil McFarlane told the Washington County Public Affairs Forum on Monday, according to the Portland Tribune. “They are necessary to keep our region moving and our arterials flowing.”

Why is the head of a transit agency actively promoting freeway expansion projects?

The fourth project, McFarlane said, is a proposed light-rail line through Southwest Portland into Tigard and Tualatin, along either Barbur Boulevard or Interstate 5.

McFarlane’s words come as the state legislature is, for the second time in three years, meeting behind closed doors in an attempt to strike a late-breaking grand bargain that would increase the state’s transportation taxes and spending. A similar 2015 attempt collapsed at the last minute amid false claims by Gov. Brown’s administration that the state could reduce carbon emissions by widening its freeways.

Let’s ask: does Portland even need to be “fixed”?

Also quoted in Monday’s Tribune article: Senate President Peter Courtney. Courtney, a centrist Democrat from Salem, reportedly told the Tribune’s editorial board that “he heard a clear message from a number of groups about traffic congestion: ‘Fix Portland.'”

Let’s leave aside the questions of who these “groups” are and how large their number is, though the Tribune’s phrasing might remind close readers of BikePortland of the unnamed “stakeholders” who the Oregon Department of Transportation once cited as its reason to continue forcing bikes and cars into the same 45-mph lane on Barbur. (The stakeholders turned out to be the Portland Business Alliance, a regional chamber of commerce, and essentially no one else.)

Let’s also leave aside, for a moment, the suggestion (also endorsed by failed Republican gubernatorial candidate Bud Pierce) that the next lane added to various Portland freeways will be the one that never fills up.

Instead let’s ask: does Portland even need to be “fixed”?

Coming from Courtney, the implication is that Portland’s transportation situation is uniquely problematic, a statewide concern because its traffic congestion is a burden on the state’s economy.

It’s certainly true that the Portland region is light on freeways. We have fewer lane-miles of freeway per resident than all but four U.S. metro areas. And it’s true that cars and trucks often get backed up on our freeways, especially since the local economy started roaring back from the Great Recession to become the fastest-growing regional economy in the country, creating 71,000 jobs in eight years and driving the unemployment rate to 3.4 percent in the midst of a population boom.

Image: Google Street View.

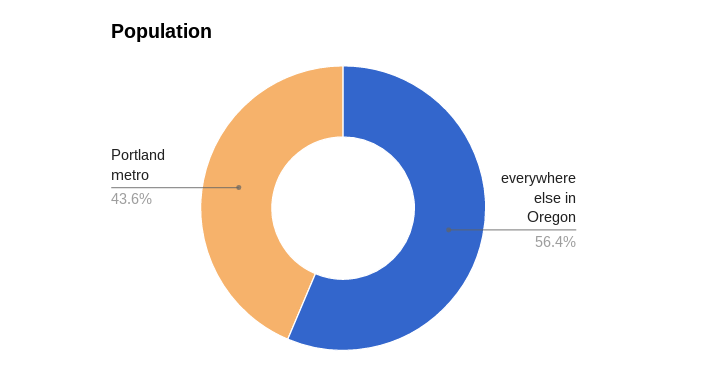

But let’s take the claim of Courtney’s unnamed stakeholders seriously and consider whether the Portland region’s admittedly congested freeways are dragging down the state’s economy. First, let’s look at the population of Multnomah, Washington and Clackamas counties as a share of the state population:

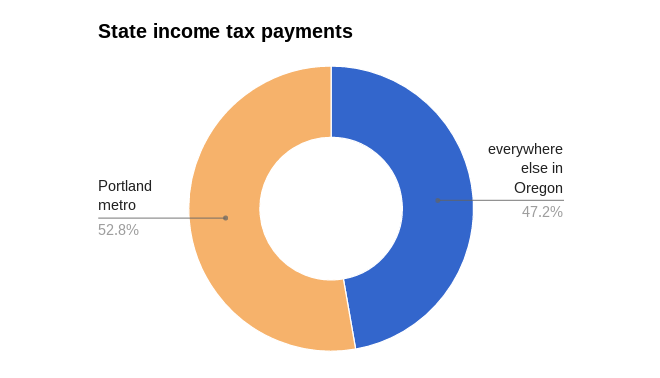

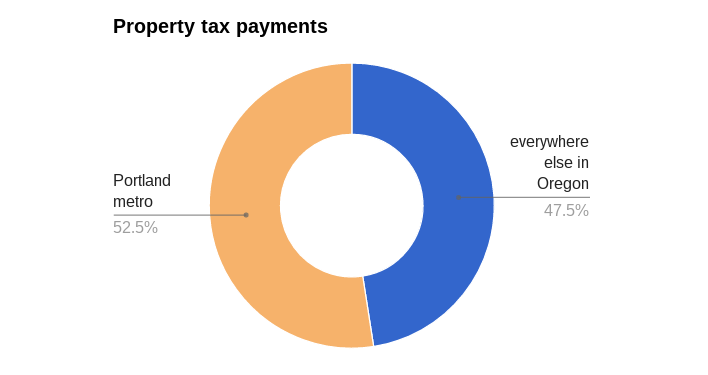

And let’s compare that to the taxes the state collects from the Portland metro area.

So despite their rush-hour struggles with congestion, Portland-area residents are unusually productive for the state. But what about Portland’s very visible poverty (another frequent complaint of the Portland Business Alliance, as it happens)? Is it a drain on taxpayers?

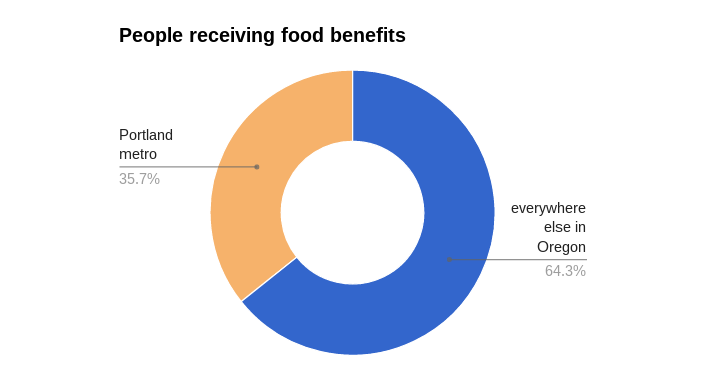

It’s hard to answer this question precisely, but let’s make an estimate by considering the location of Oregonians who receive food stamp benefits.

So not only is the Portland metro area providing more than half the state’s tax revenue, it’s using a disproportionately small amount of food benefits. (And to be fair, this is mostly because of very low food benefit claims in the suburban Washingon and Clackamas counties — Multnomah County leads the state on many economic measures but it’s in the middle of the pack on food benefit rates.)

Advertisement

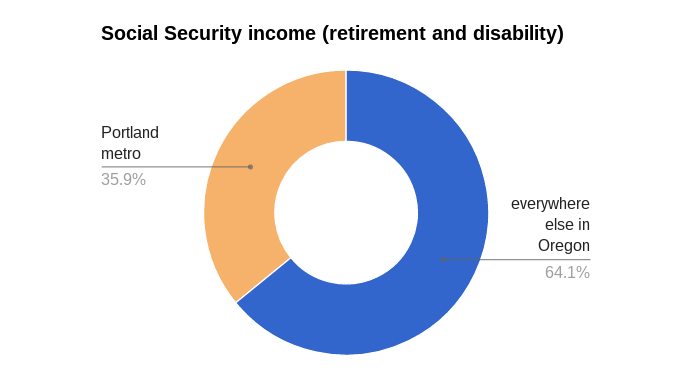

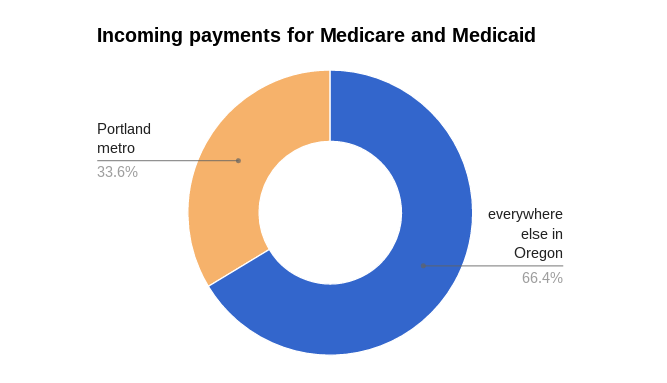

What about the country’s other three biggest social programs, Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid?

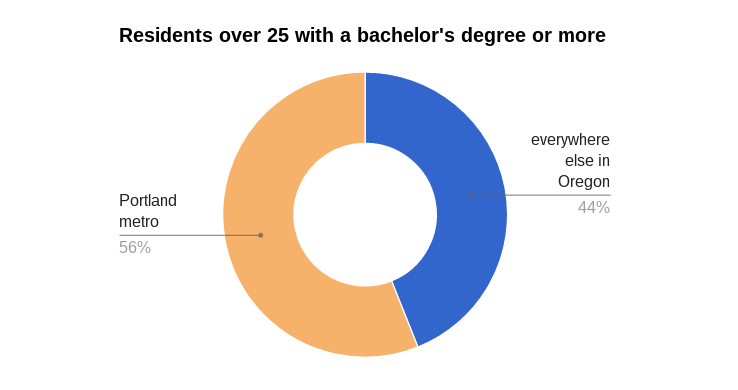

OK, now let’s stop focusing on all these costs of a civilized society, and check some things we know are good. For example, there is no more reliable predictor of future economic growth than education. So where do Oregon’s college graduates live?

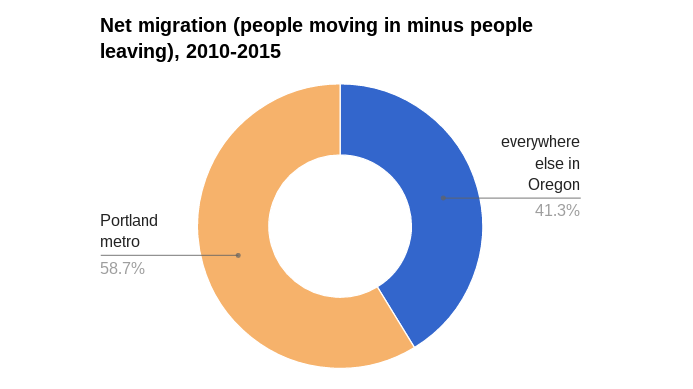

Lastly, let’s look at maybe the single simplest measure of whether a place is succeeding — whether people are moving there faster than they’re moving away. Here’s what that looks like:

Every picture tells the same story: The freeway-poor Portland area is not only a non-burden on the state economy. It is the main force driving the state economy. The Portland region is out in front of the rest of the state’s economy and much of the rest of the state is drafting off it.

Here is a different Google Street View of Interstate 5. This one is from Woodburn, a city in Sen. Courtney’s district. Food benefit usage is 56 percent higher than in the Portland metro, median incomes are 26 percent lower and bachelor’s degrees are 63 percent less common. Since 2010, the city has added 641 additional residents. But freeway traffic is pretty light!

Is the point of all this that cities outside the Portland area are bad or worthless? Absolutely not — there’s a lot more to life than money. Is the point that Portlanders shouldn’t be paying more than they receive in public services? Not at all, and in fact Portland-area residents tend to be enthusiastic about all the services listed above. Generally speaking, all they ask is to be allowed to continue their disproportionate funding of public services, which improve the state and country for everyone.

The point of all this is that traffic congestion is not a cause of economic collapse. It is an effect of economic success.

In fact, the choices that lead to congestion — a relatively compact urban area that hasn’t been sliced up by freeways, and has spent its money on things like mass transit and libraries and parks and restaurants instead — might actually be a cause of economic success.

It is true that the Portland area’s auto congestion is annoying. But attempting to “fix” it — at least in the way that Courtney and apparently TriMet are urging us to — is the last thing Oregon’s economy needs.

It’s worth wondering whether your state legislators have been hearing that from anyone.

Thanks to Charlie Tso for calling attention to the Tribune piece.

— Michael Andersen: (503) 333-7824, @andersem on Twitter and mike.andersen@gmail.com

BikePortland is supported by the community (that means you!). Please become a subscriber or make a donation today.