(Photo: PBOT)

Portland is changing and so are our streets. Whether those changes help or harm our city is entirely up to us.

One of the biggest changes is an increase in the amount of people who drive. Congestion is everywhere and one of the victims are bus users. During peak hours especially, they get stopped behind single-occupancy vehicles. It’s maddening when public transit is delayed by such an inefficient and costly mode of transportation.

One way the Portland Bureau of Transportation has decided to deal with this problem is to focus on getting cars out of the way of buses. For the past year or so they’ve worked on the Enhanced Transit Corridors plan, which is now in draft form and open for public comment (until March 26th, sorry for late notice). The plan aims to institutionalize the concept of “enhanced transit” within the City of Portland, and to identify projects that will improve transit capacity, reliability and travel time.

Before I share my takeaways, here are some kicker quotes from the plan that sum up where PBOT is coming from:

“Portland and the region is at a critical point in the evolution of our transit network. Our buses are increasingly stuck in traffic, and each year resources for transit hours are spent just trying to keep up schedules due to congestion, reducing the potential funding to increase transit service. This critical point calls for redoubling our efforts to improve transit…

A common criticism of the existing transit network is that it takes too long to cross downtown Portland or to get to any destination compared to driving. We are losing the attractiveness of transit every year as buses are stuck in traffic, not taking people where they want to go at a competitive travel time.”

Here are my takeaways…

We desperately need better bus service

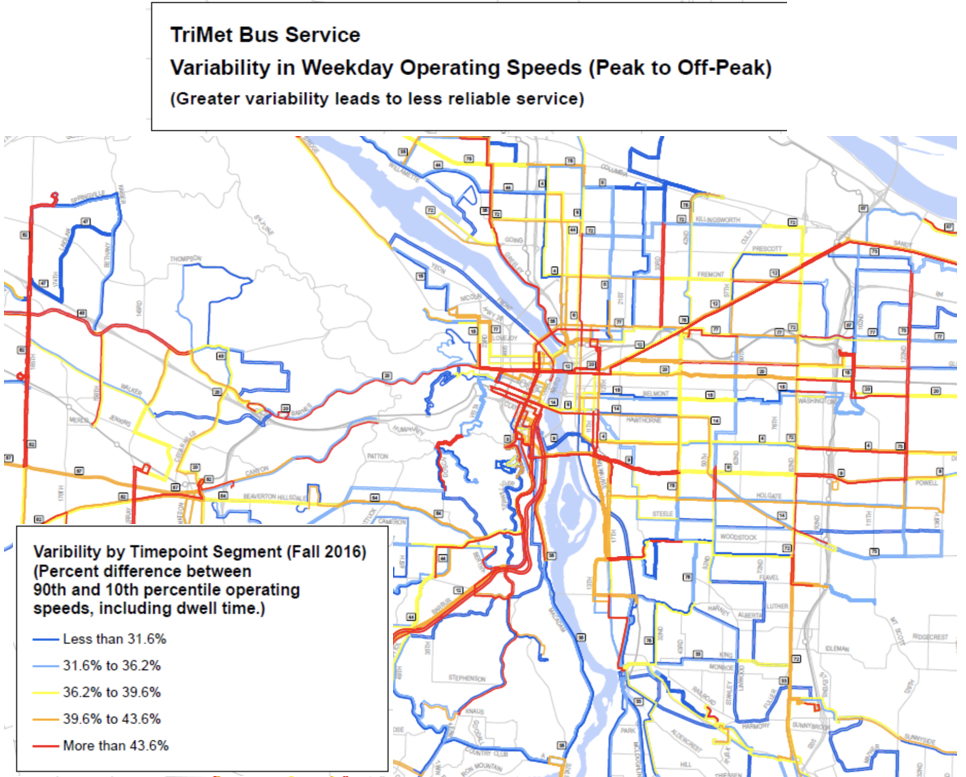

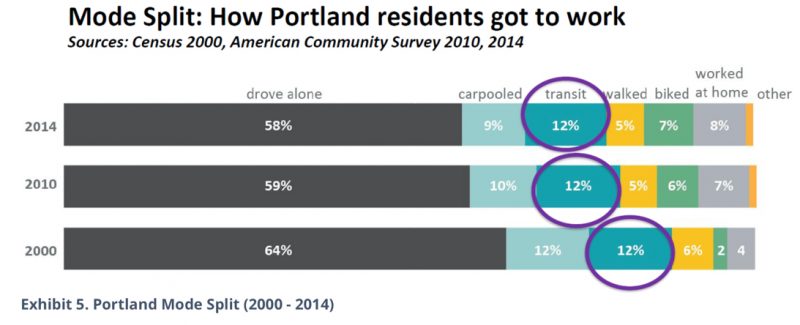

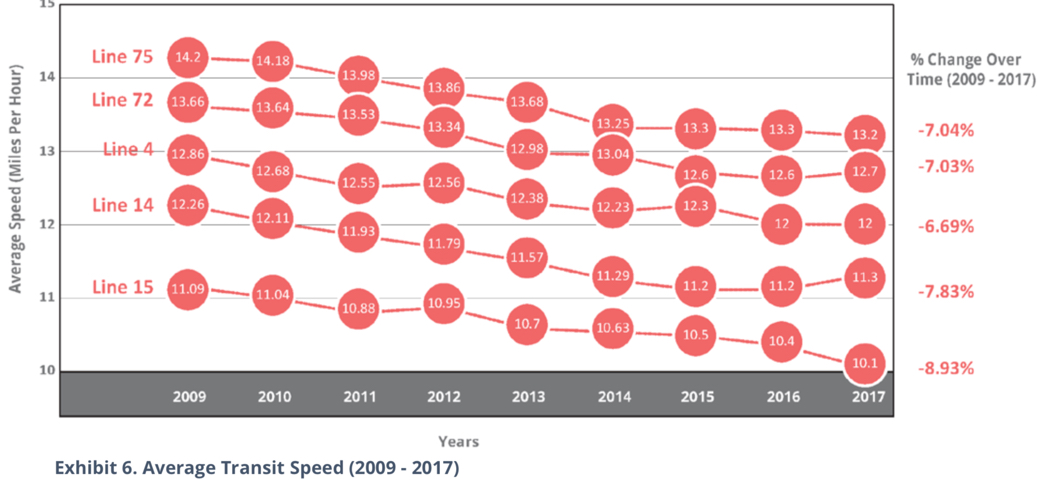

The trendlines for congestion, population growth, and transit use are not in sync. Transit use in Portland is stagnant, while congestion increases and the experts project Portland will add another 260,000 new residents by 2035. “Without substantial improvements to the bus and streetcar network,” the plan states, “it is very likely that transit service speed and reliability will continue to deteriorate.”

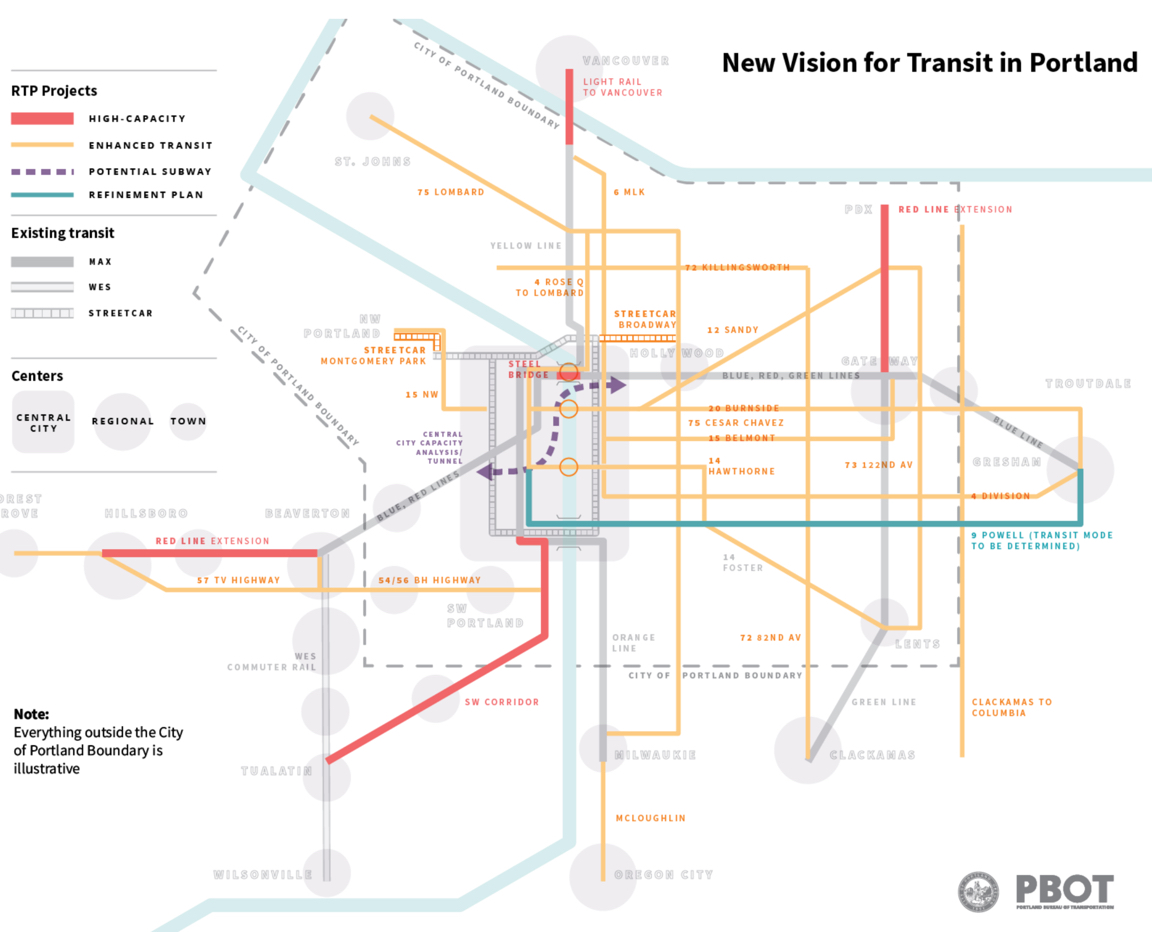

Portland’s transit mode share goal is 25 percent of all trips by 2035 (part of a goal to have 70 percent of all commuters do something other than drive a car). While MAX light rail has increased in recent years, the amount of people using local buses drags down the current transit mode share down to 12 percent — the same level since about 2000. PBOT recognizes that TriMet already has an established “backbone” of frequent service routes like the 4, 72, 20 and 75. They’ve smartly focused this plan on those routes.

Buses are flexible, relatively cheap (compared to MAX and freeways), and when done right they can integrate very nicely with bicycle use. If we don’t make them work better, we’re in a lot of trouble.

Too much driving is screwing everything up

We could write volumes about how car abuse is hurting Portland. But let’s look specifically at its impact on bus service.

From the plan:

“… buses and streetcars are increasingly stuck in traffic, leading to longer travel times and less travel time reliability, making bus and streetcar transit less competitive with driving, bicycling, and other transit modes.”

And here are the charts to back that up:

Advertisement

PBOT wants into the transit game

Transit plays a crucial role in whether or not Portland reaches its transportation goals. The problem is, PBOT doesn’t control much of it. Beyond funding operations and some other ties, TriMet manages their own bus and MAX service and Portland Streetcar Inc. operates separately from the City of Portland. PBOT currently has staff with titles of Bicycle Coordinator, Freight Coordinator, and Pedestrian Coordinator — but not Transit Coordinator.

That might be changing.

The ETC plan feels like a serious attempt by PBOT to play a larger role in transit. The plan calls for a “closer relationship and active cooperation between transit operators and PBOT” and the development of a City Transit Program. PBOT also wants to, “Develop future MOUs [memorandums of understanding] and IGAs [inter-governmental agreements] to further forge TriMet and PBOT partnerships.”

And you know they’re serious when they put money on the table. PBOT wants to create a new program for “transit priority spot improvements” that would be funded at $500,000 annually (the fact that the plan comes out when the agency is flush with cash for the first time in decades probably isn’t a coincidence).

A subway!

It’s nice to see PBOT share a bold vision of anything these days. Look closely at their “new transit vision” and you’ll see a “potential subway” under the Willamette River between downtown and the Lloyd District.

Listed as a possibility to be built in the next 20-40 years, PBOT calls the subway one of several major new transit “concepts” that can, “make transit more attractive and competitive while maintaining the basic accessibility that transit needs to attract riders.”

Red is for buses only

If the ETC gets adopted by City Council, PBOT is going to join an ongoing study at the Federal Highway Administration that’s analyzing the effectiveness of red-colored lanes for buses. San Francisco is already using red for bus-only lanes.

PBOT took this same step with green for bike lanes (and bike boxes).

What does this mean for bikes?

It’s mostly good, but I remain cautiously optimistic.

The ETC plan is just one part of PBOT’s larger work to redefine our streets. That new definition pushes single-occupancy driving nearly out of the picture and elevates cycling, walking, and transit into starring roles. Keep in mind that PBOT isn’t doing this ETC work in a vacuum. In the near future, when they look at a street to fix a major safety problem, they’ll also lean on the ETC plan to determine whether transit upgrades could be made at the same time. Likewise with bike-centric projects.

In fact, PBOT is already talking about an integration between the ETC and the Central City in Motion plan. That’s the plan to build a network of family-friendly bikeways they’ve been working on for many years (more to come on that soon).

But their are pitfalls. As we know, right-of-way is precious and more space for buses means less space for everything else. It’s possible for buses and bikes to coexist wonderfully together — but if things like bus-only lanes, floating transit islands, and curb extensions (all recommended in the ETC toolkit) aren’t built with low-stress cycling in mind the result could be a reduction in service for bicycle users.

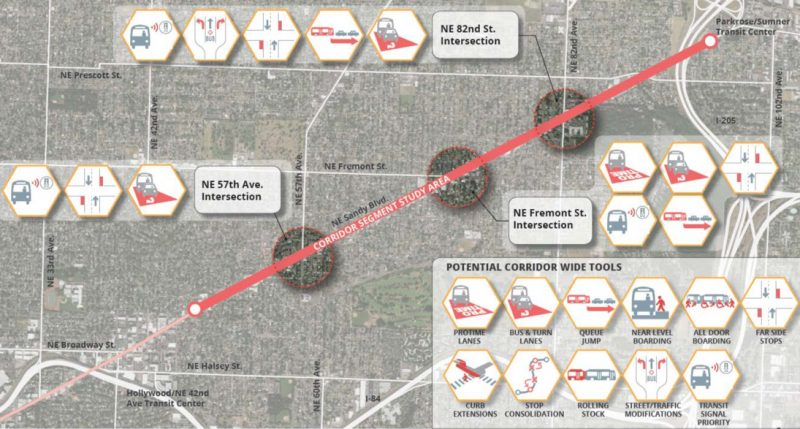

For example, below is a graphic from the plan of a potential enhanced transit project on NE Sandy. Keep in mind that Sandy also needs a protected bikeway in the future. Can we do all the stuff in the graphic below and still make Sandy the great cycling street it’s meant to be?

I’m glad to see this potential for conflict is acknowledged in the ETC plan. “Great care must be taken when implementing… treatments that can reduce the safety and comfort of people walking or bicycling, or preclude the future provision of appropriate bicycle facilities on streets classified for bicycle use,” reads one passage. Another section warns that according to the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO), “[Shared] bus-bike lanes are not high-comfort bicycle facilities, and are not a substitute for dedicated bikeways,” and that, “Special care must be taken not to require bicycle and bus traffic to mix at high speeds.”

Learn more about the ETC plan at PBOT’s website.

— Jonathan Maus: (503) 706-8804, @jonathan_maus on Twitter and jonathan@bikeportland.org

Never miss a story. Sign-up for the daily BP Headlines email.

BikePortland needs your support.