— This article is by Portland-based author, Lois Leveen.

The community protects the community. That is the very essence of corking.

Most BikePortland readers are familiar with corking from our participation in group bike rides: individuals intentionally block cross-traffic at an intersection until all the ride participants have passed through, to prevent motor vehicles from endangering riders. Perhaps you are someone who loves to cork. Sensing a need to ensure the well-being of the community. Assuming a space of vulnerability. Practicing skills of de-escalation while demonstrating to drivers how we engage in bike fun.

Or perhaps you are someone who appreciates not having to cork, knowing as you move along with the group that other members of a ride are keeping you and everyone else safe.

As vehicular violence increases locally and nationally, there is something truly beautiful about the fact that a bunch of random Pedalpaloozaing strangers who meet up in a park dressed as cats, or dressed in teal, or fanning it up over Angela Lansbury — can calm traffic.

The community-oriented act of corking contrasts with the refractory and dangerous stance of the Portland Police Bureau, which has repeatedly declared that reckless driving is so out of control in Portland, there is nothing they can do about it. This claim encourages illegal and dangerous driving. It also obscures how effective and how radical the simple act of corking can be.

In the summer of 2020, when the group rides of Pedalpalooza were canceled due to COVID, some bicyclists brought the corking practice of community care to Black Lives Matter protests, eventually developing corking protocols specifically for supporting racial justice activism. I can remember how moved I was when, after months of pandemic isolation, I crested a rise on my way to a racial justice rally at Fernhill Park and saw a coordinated group of bicyclists and motorcyclists positioning themselves to protect the marchers. The community protects the community.

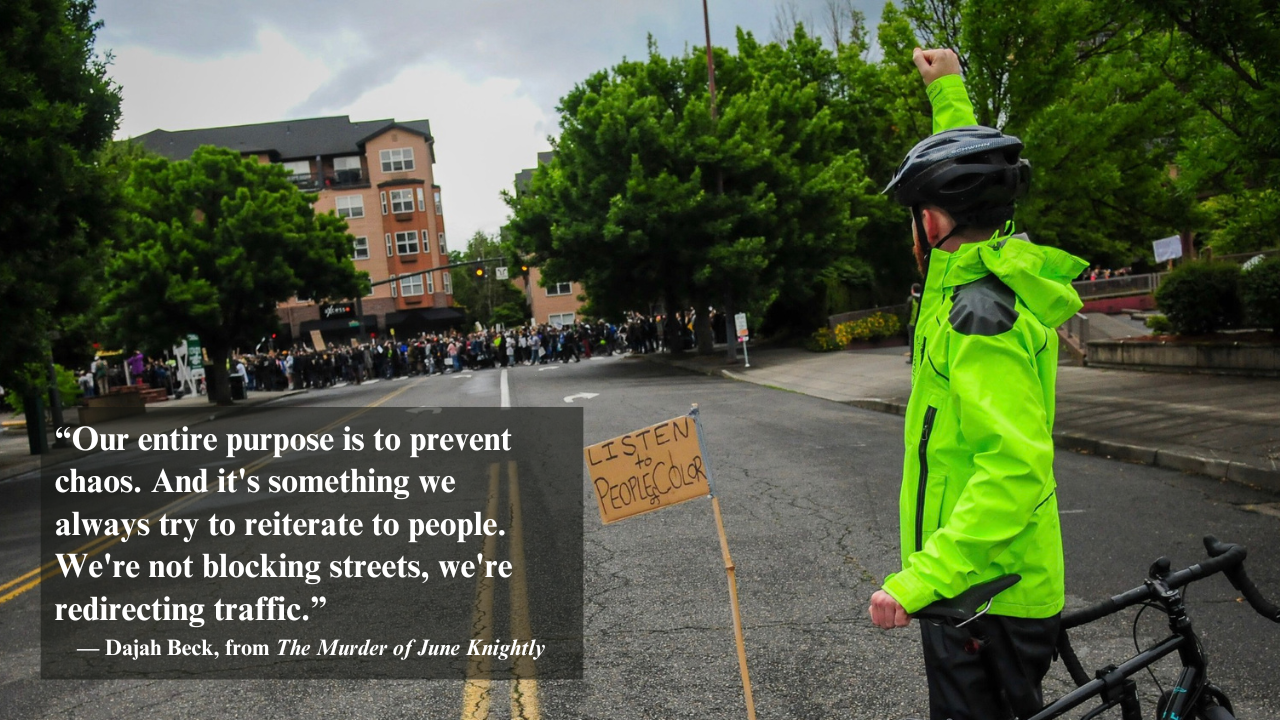

That same summer, a racial justice march passed by the home of June Knightly, and she was so inspired she began corking regularly, taking the moniker T-Rex as her nom de cork. Knightly, who walked with a cane, didn’t cork on a bike. As protests grew larger and the logistics of keeping them safe became more complicated, the focus and strategies for protest corking evolved to include cars along with bicycles and motorcycles. This wasn’t the only adaptation made to protect large protest marches. Whether I am corking a bike ride or relying on corkers when I lead a ride, I define the purpose of corking as ensuring vehicular traffic pauses long enough for bicyclists to pass safely. Dajah Beck, who became friends with Knightly as they corked together, describes protest corking differently: “Our entire purpose is to prevent chaos. And it’s something we always try to reiterate to people. We’re not blocking streets, we’re redirecting traffic. Our whole purpose is to keep traffic moving.”

On February 19, 2022, as Knightly, Beck, and other corkers gathered in Normandale Park before a march demanding justice for Daunte Wright and Amir Locke (Black men killed by police officers in separate instances in Minneapolis-St. Paul), a white supremacist wearing a t-shirt proclaiming, “Kyle Rittenhouse is a true patriot” approached and began verbally harassing and threatening them, using a misogynist slur. Enraged by their refusal to engage, he charged at one of the corkers. Then, in that dark corner of the park, he pulled out a gun, killing Knightly and shooting four others, one of whom remains permanently paralyzed.

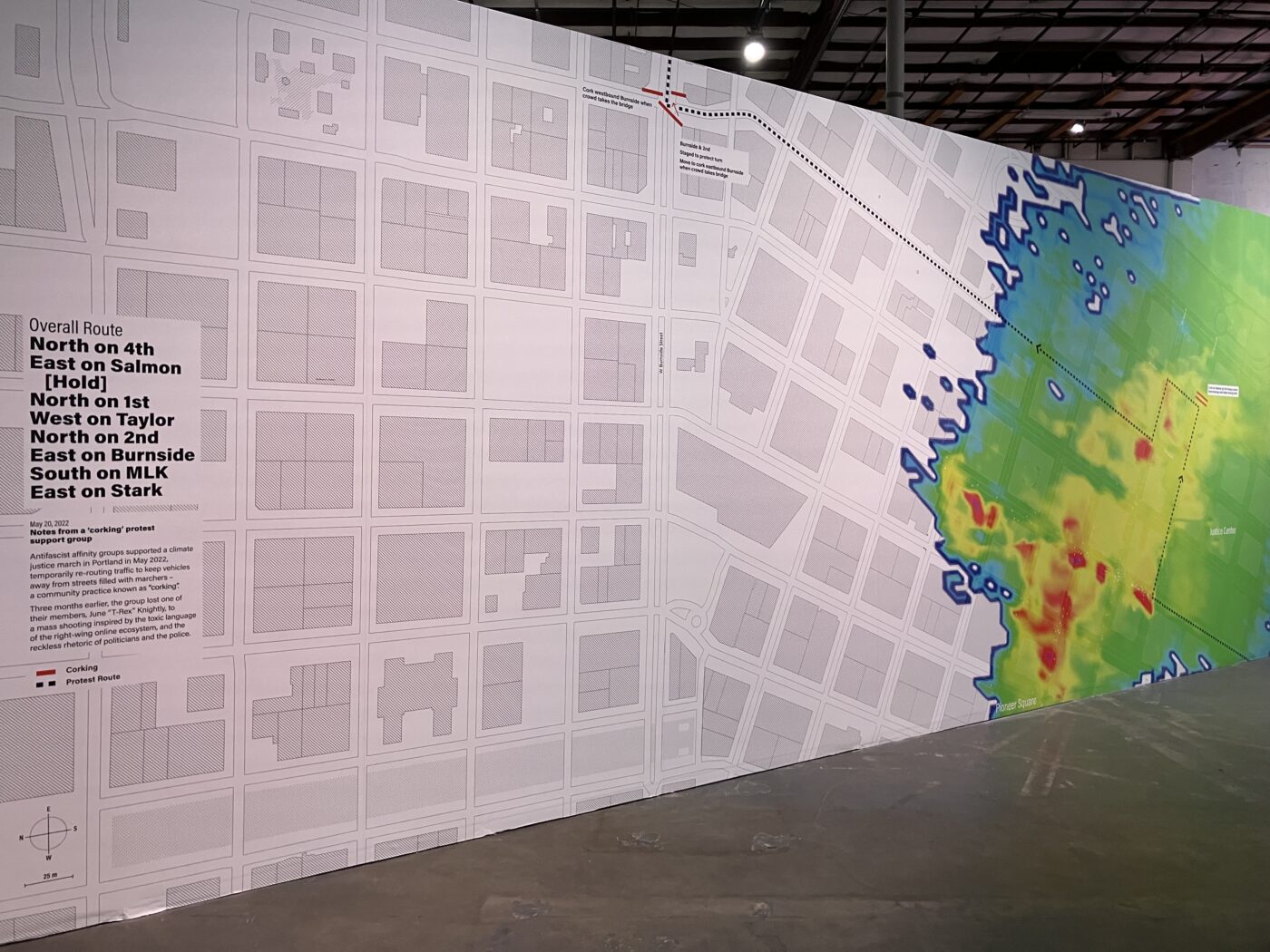

“The Murder of June Knightly,” a video produced by a team of researchers working collectively under the name Forensic Architecture, reconstructs the events leading up to and following the attack. It is currently on view at Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (PICA), as part of a larger exhibition entitled Policing Justice. (The quotations and other details I’m including in this post are taken from the video – which includes footage of the shooting recorded on a helmet camera – and from an article about it that was published in The Guardian). “The Murder of June Knightly” and the PICA exhibition as a whole provide a disturbing, moving, and ultimately hopeful understanding of our city, one that all community-minded Portlanders should experience.

The exhibition situates the recent years of racial justice protests and the Normandale Park shooting within a larger history of abuses by Portland police. It also addresses decades of local policies and practices like redlining, land forfeiture, and environmental racism that have targeted Black Portlanders in particular. The harm resulting from these practices extends far beyond those who have been directly targeted, as “Tear Gas Tuesday in Downtown Portland,” a second video by Forensic Architecture included in the exhibit, methodically documents. If you were bicycling, walking, playing, living near, attending school, or working in areas of Portland proximate to where Portland police and federal forces deployed tear gas at protestors, you were exposed to highly toxic substances banned by the Geneva Convention. In one night of June 2020 alone, our air contained levels of toxins hundreds and even thousands of times higher than the levels that federal agencies have determined are “immediately dangerous to life and health.” These toxins entered the soil and the Willamette River, doing lasting damage to the entire ecosystem.

Grim as such details are, the PICA show simultaneously reflects the dedication and the determination that drives social justice activism: a belief that we the people can improve our city and our country. As journalist and activist Mac Smiff notes in the exhibition catalogue, “Policing Justice” seeks to “explore Portland’s history of policing in relation to racial, environmental, spatial, and juvenile justice; give voice to the lived experiences of those most directly impacted by police misconduct and the criminal injustice system; and create space to imagine a multitude of possible futures for public safety that are intentionally inclusive and driven by community.”

Given the urgency of those first two goals, it is notable that they are integrally linked to the third. During a symposium at PICA, Kayin Talton Davis, who works for the Albina Vision Trust and who collaborated on several pieces in the exhibition, reminded the audience that for many Portlanders (and many Americans), asking, “what does my future look like?” is “a radical and essential question.” Another of the artists, Robert Clarke, posed an equally radical and essential question: “What is your vision for a world where you are not policed, where you don’t have to fear for your lives?”

Compared to other nations, America incarcerates a far higher portion of our population; prioritizes spending public dollars from on policing and incarceration rather than fully funding healthcare, education, affordable housing, clean water, and other basic necessities; and sacrifices more than 1,000 Americans who are killed by the police each year (a number that continues to increase even after outcry following the murder of George Floyd), amounting to execution without trial or conviction. Despite these evident failures, policing is so ingrained across our society that most Americans cannot begin to envision an alternative. Bicyclist, pedestrian, and public transit activists, deeply concerned about America’s deadly addiction to car culture, must counter a similar inability of most Americans to envision and embrace safer, more healthful, and more community-oriented alternatives. (This analogy between dismantling car culture and dismantling the carceral state is especially relevant because, as the book Cars and Jails shows, America’s dependency on cars and car culture dramatically contributes to America as a carceral state.)

And yet, the alternatives we need to envision begin with the same simple truth: The community protects the community.

Ben Smith, the white supremacist shooter, intentionally targeted June Knightly, Dajah Beck, and their friends as they stood far from where racial justice protestors were assembled on the other side of Normandale Park. As corkers, they had cared for and protected fellow community members countless times, and on that night, it was community members who came to their aid. Trained volunteers who were supporting the march disabled and disarmed Smith (without harming any bystanders), and immediately began administering medical aid to everyone who had been shot, including Smith. By contrast, when ambulances arrived, they were delayed in treating anyone because the 9-1-1 operator dispatched Portland police who insisted on first interrogating those who had been targeted, treating the racial justice activists with open suspicion. Despite the testimony of the victims and witnesses and the helmet camera footage provided by the corker, in the hours that followed the Portland Police Bureau intentionally released a public statement with misinformation about what had happened. The police crafted a false narrative to make it seem like the incident began with armed protestors threatening a homeowner. Two years later, the Portland Police Bureau continues to promote this false and dangerous version of the event.

During my most recent visit to PICA, I watched “The Murder of June Knightly” along with two other people, a young man and an older woman who (based on their responses to the video) may have known one or more of the people who were shot. We were the last three people in the gallery that day, and the quiet of the space made the weight of what we were seeing even heavier to bear. But the video doesn’t end with the shooting, nor with the police circulating the false report that was picked up across local and national news and right-wing social media. It ends with June’s friends corking again, as they have regularly done in the two years since they were attacked. The footage of this more recent corking includes a joking exchange with an annoyed driver, one that deescalated the driver and made all three of us viewers laugh out loud (thank you, corker). The final image and sounds in “The Murder of June Knightly” are of teens chanting and marching, demonstrating once again that we the people have the power and the responsibility to make our city and our country better. The community protects the community.

— Policing Justice is on view Thursday & Friday, 12:00 – 6:00 p.m. / Saturday & Sunday: 12:00 – 4:00 p.m., through May 19, at PICA, 15 NE Hancock Street, Portland. Exhibit website.