Many Portlanders are frustrated that the vast majority of bike lanes in our city lack a key safety feature: physical protection from drivers and their cars. Video of a recent collision on Northeast 21st Avenue was viewed by tens of thousands of people before it was taken down at the victim’s request. It showed a driver veer into the bike lane and strike a rider, sending them high into the air and flipping their body head-over-heels multiple times before landing on the sidewalk.

Those who saw the video witnessed the horrific consequences of relying only on paint and flexible plastic posts to separate bicycle riders from other road users. And despite potential for more injuries and deaths, the perception of danger that keeps the vast majority of Portlanders from riding bikes will persist until they see more serious separation from drivers.

We’ve made progress in the past 15 years, but not nearly enough to keep up with growing threats. As street culture has eroded to its lowest point ever and more people drive distracted and without respect for others, the need for hardened, physically-protected bike lanes has reached a fever pitch.

Serious pressure is mounting on the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) to beef up bike lanes just as their budget is in its worst condition ever and its commissioner-in-charge is mounting a campaign for mayor.

Something’s got to give.

A brief history of protected bike lanes in Portland

We first discussed protected bike lanes in 2007. The Portland Bureau of Transportation has experimented with them since 2008, and the first major one was built on Southwest Broadway in 2009. Almost from the start of when protected bike lanes became popular in the U.S., Portland had trouble building them. We used to hear that these new, more politically-fraught bike lane designs required strong support from the “bike community.” City Hall staff would hear bike advocates arguing over whether protection was even necessary (due to a “vehicular cycling” philosophy from riders who don’t like being boxed-in) and it gave them cold feet.

But like most new ideas, once Portland built a few of them and the sky didn’t fall, they became more-or-less a standard treatment. In 2011 we shared several projects that illustrated PBOT’s commitment to separating bike users from car users. Back then I hoped/expected that the debate was over and we’d start building every new bike lane with protection from the get-go.

In 2015, former PBOT Director Leah Treat wrote a memo to all staff that stated,

“Make protected bicycle lanes the preferred design on roadways where separation is called for. I am asking for this design standard for retrofits of existing roadways as well as to new construction. I want protected bikeways to be considered on every project where some type of separation is desired.”

We should have been on our way. But despite garnering national headlines for this new “policy” (which was never a policy, just an aspirational memo), it didn’t really turn out like we’d hoped. New projects were built without physical separation and we never saw a large campaign to retrofit old bike lanes with new protection.

Frustrated by the lack of progress, in 2016 BikePortland laid out all the reasons PBOT had for why they couldn’t do more. In a 75-page technical memo, PBOT Bike Planner Roger Geller summarized the top four challenges the city faced in building protected bike lanes: fire truck access issues; stormwater/runoff requirements; auto parking space buffer zone, and truck and bus turning radius requirements. (Recall the flex-post debacle on the NW Lovejoy ramp in 2012 and you’ll begin to see how space constraints influence PBOT’s decisions to keep bike lanes unprotected.)

Another reason was the lack of an official, internal engineering design guidebook for how to build protected bike lanes. PBOT didn’t have one of those until 2018 (and it wasn’t released publicly until 2021).

But the presence of excuses didn’t remove the need for protection.

12 years after Portland first started talking seriously about protection, PBOT installed their first concrete curb separated bike lanes (on North Rosa Parks Way in 2019). Now the treatment is all but standard on PBOT projects and they’ve even retrofitted a few existing, paint-only lanes with some level of protection like flex-posts, plastic “tuff-curbs”, large concrete planters, and so on.

But there are still miles of dangerous, unprotected bike lanes in Portland.

Advocates push for protection

“The bike lanes on this section of NE 21st are separated from head-on traffic only by plastic delineator wands,” the board of nonprofit BikeLoud PDX wrote in a letter to the PBOT director and safety staff this morning. “These plastic flex-posts are everywhere in Portland. Look for them the next time you cross a bridge — battered by drivers, and often missing where they’re most needed.”

The nightmarish collision on NE 21st spurred BikeLoud into action. Their letter references BikePortland’s 2016 review of the 21st Ave bike lane project where commenters warned that a head-on crash with a driver was likely and that fixed bollards were needed.

BikeLoud is demanding that PBOT install metal bollards or some type of physical protection not just on 21st Ave, but on any street where two-way or contra-flow bike lanes expose cyclists to head-on traffic. They also want PBOT to closely track where plastic flex-posts are frequently replaced and upgrade them with physical barriers. The letter also calls for physical protection to be used on all new bike lane projects.

The 21st Ave collision has also inspired a new group of tactical urbanists dubbed Block Ops PDX who have taken matters into their own hands with a mantra on their social media profile that reads, “Infrastructure by people for people.” On September 6th, they installed several concrete blocks in the buffer of the bike lane where the person was struck. Within hours, the group said on their X account, “another reckless driver struck one of the bollards.”

A few days later, PBOT crews removed the unsanctioned traffic features. “This attempt resulted in concrete blocks in the bike lanes and cost the bureau time and labor to remove and fix, taking away resources from other safety work that was planned this weekend,” PBOT wrote in an X post. They said the concrete blocks created a safety hazard and urged people to not make any further unauthorized changes to streets.

So far it appears Block Ops will continue their work. “We’ll strike again soon,” they posted this morning.

(UPDATE, 2:37 pm: PBOT Public Information Officer Dylan Rivera reached out via email to say, “Our engineers have conducted a site visit on NE 21st and are developing plans, but it’s too early to provide more details than that at this time. Safe to say that yes, this is on our radar and we are looking into it.)

PBOT: “We’d love to be able to provide more protection, but…”

All this pressure on PBOT and its Commissioner Mingus Mapps (who was forced to call a press conference after a record 13 people were kill in traffic crashes in July) comes at a time when the agency is fighting for its financial life. With inflation spiking material and construction prices, dwindling resources from a lack of parking and gas tax revenue, an unexpected demand for homelessness-related expenses, and a city budget that all but ices transportation out of the General Fund, it’s desperate times for PBOT.

PBOT Communications Director Hannah Schafer told BikePortland Monday that, “We’d love to go out and harden a lot of those bikeways where we have only plastic delineators, but we don’t have the money. We are looking at a $32 million cut, which is a third of our discretionary funding.”

Schafer contends that cost is the main issue, and that lack of roadway space is another, yet far less pressing, one. It was easy to hear the emotions and concern about the budget in Schafer’s voice. “There’s a lot of feelings of frustration that we can’t do the work that we know we need and want to do… We don’t like not being able to do what we know we need to do to make our city and our transportation system function.”

“Some of the way we talk about it and the way that BikeLoud talks about it might sound a little different,” Schafer continued. “But I really don’t think we’re that far apart.”

Funding to retrofit existing bike lanes with protection would come from PBOT’s General Transportation Revenue (GTR), a discretionary pot that has allowed their Quick Build program to flourish for years. That program funds small capital projects (usually under $500,000) and many of the bike lane projects you see around your neighborhood. And it’s GTR that’s on the chopping block as PBOT girds for very uncomfortable budget negotiations later this month.

“Until we find a way to right-size, the General Transportation Revenue and find more stable funding, we will never have the money to go out and do that (Quick Build type of) work,” Schafer said. If the funding problems aren’t ironed out, PBOT will only do projects that can be funded through larger, project-specific grants (like ones for the N Willamette, Better Naito, NE 47th, and 122nd Ave projects). “So in parts of town where we’re not doing that big project, they’re going to feel less and less served,” Schafer explained.

Doing more with less

Since PBOT is low on cash, the natural next question is: How much money do they need?

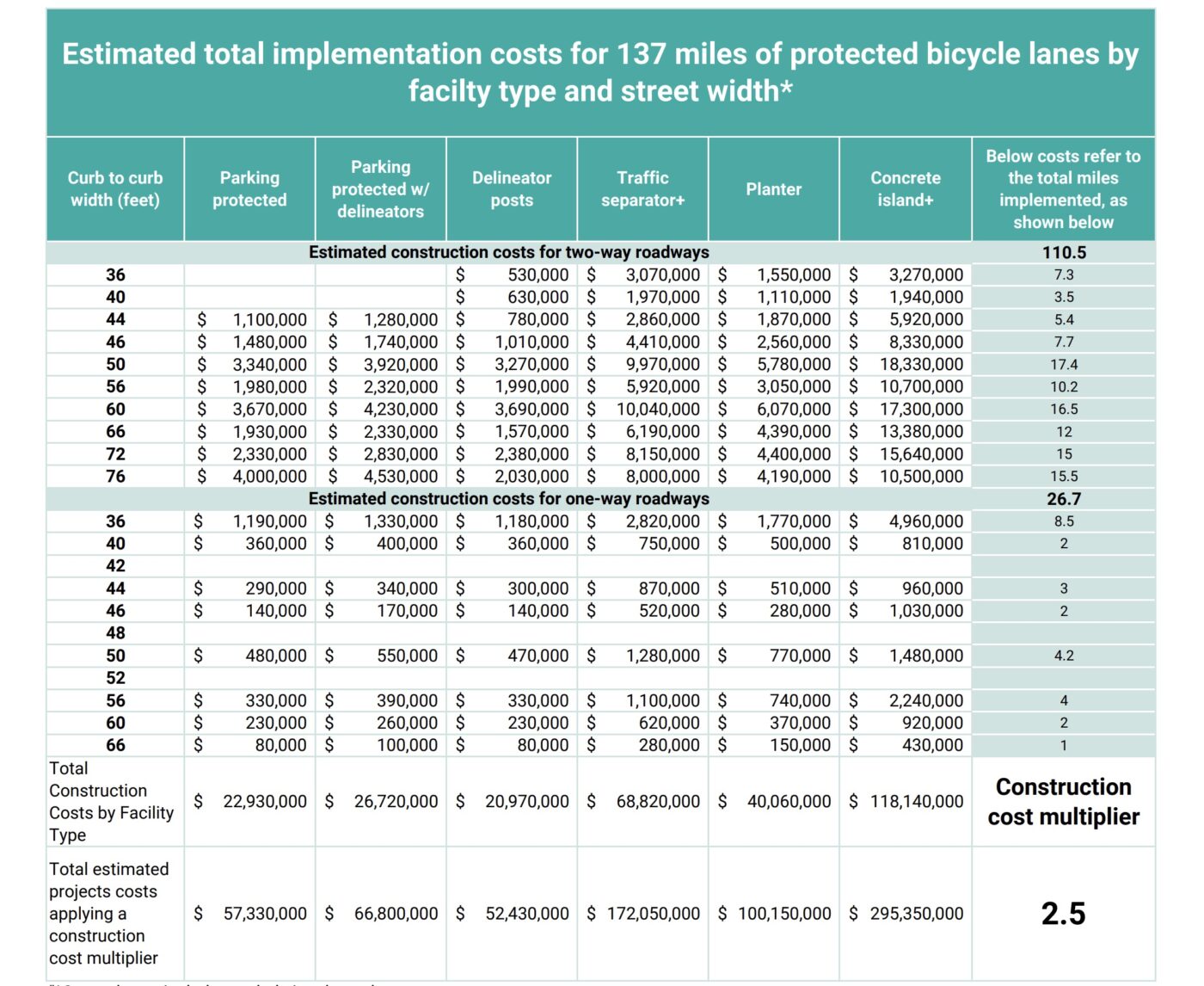

In their 2018 Protected Bicycle Lane Planning and Design Guide (above), PBOT laid out detailed cost estimates for all the different levels of protection — from flex-posts, all the way up to concrete islands. The cost estimates in that guide are woefully outdated due to skyrocketing inflation on construction materials (which PBOT has told me has gone up 50% in less than three years), but the relative cost differences are still valid.

In general, on a per-mile basis, a bike lane with a full concrete median island costs PBOT about six times what it costs for them to use flex-posts. In 2018 dollars their report said it would cost $295 million to build 137 miles of concrete island protected bike lanes (not including traffic signal work) and just $52 million for flex-posts (an online inflation calculator says those figures are $355 million and $62 million in 2023). A traffic separator (some type of shorter, plastic curb) would be about half as expensive as a concrete island and three times the cost of flex-posts.

If PBOT’s budget gets hammered as much as some people fear, we’re not likely to see any retrofitting of existing bike lanes and we’ll only get new protected bike lanes as large, grant-funded projects get built. But if the budget can be stabilized, there’s a chance more protection can climb up the list of funding priorities.

Whatever the future holds, if advocates want more protected bike lanes, they’d be wise to think about two approaches: attach their pitches to PBOT’s Vision Zero Work Plan (which will have an update published later this year), and find opportunities to phase it in.

A good example of the phased-in approach is PBOT’s work on Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway. It started out as a five-lane road with paint-only, five-foot bike lanes. Then in 2013 they re-striped two miles of the road with a buffer at a cost of about $20,000. Five years later they returned again and added a concrete median (see photo). It took 10 years, but it happened.

“When we don’t have funding, we create the space and then upgrade as funding becomes available,” PBOT Public Information Officer Dylan Rivera told me via email this week. That might work well for PBOT, but increasingly, Portlanders might not be willing to wait that long for the basic service of safe travel.

Another advocacy avenue might be PBOT’s Vision Zero Plan. Despite it being battered by critics amid record deaths, the plan remains the city’s guiding document when it comes to safety-related transportation funding. At least that’s how Schafer sees it. “Vision Zero will continue to be the way that we guide our safety improvements. Using a Safe Systems approach with Vision Zero as the goal, will continue to be the way that we direct our work.”

If PBOT doesn’t figure out how to protect more bike lanes soon, the only zero they’ll reach is the number of people willing to risk cycling on Portland streets.