There are a ton of reasons why cycling is down in Portland these days. Anyone who thinks the answer is short or simple has not taken the time to fully grasp what has happened in the past decade and what continues to happen today.

We need to acknowledge the problems that got us here and get everything out in the open. That’s what this post is about (and it’s long, so get comfortable).

I’ve read hundreds of comments and emails, have had many conversations, and have spent countless hours thinking about this decline. And it’s far from a new concept. We first reported that Portland’s cycling boom was over and that something fundamental about the culture of this town had shifted in a story our former news editor Michael Andersen wrote way back in May 2014 (that was part of a “Portland’s Cycling Stagnation” series we published mid-2013). Michael wrote that story because I just wasn’t able to get the words out of my brain. That’s common on issues like this — big, multi-layered ones I feel deep in my bones but have so much emotion wrapped into they’re hard to put into words. After listening to me rant for days in the office about it, Michael finally just said, “Let me write it.” And he absolutely nailed it.

The fact that the city happened to be painting over the huge “Welcome to America’s Bicycle Capital” mural downtown was a perfect coincidence and Michael’s idea to splice the article around a time-lapse of it was brilliant. We went on to publish 12 stories in a series we hoped would help get Portland back on its pedals. It didn’t work.

Personally, although I shared my thoughts on Portland’s cycling complacency and political crisis in 2015, I never fully reckoned with our decline in cycling after that. There were a lot of reasons why: I always figured it’d be a temporary blip; I’d staked my professional life on Portland being a great cycling city, so it was hard to acknowledge we were anything but; I didn’t want to demoralize the community with too much negativity; and I wanted to make space for a lot of other very important issues — like racism in urban planning, police brutality, gun violence, housing affordability and related homelessness — that began to dominate the local discourse and City Council meetings.

As a white dude with a lot of privilege and who many just think of as “the bike guy,” I knew the optics of me shaking my fist at the sky and saying, “But what about bikes?!” would not be great. So I mostly kept my head down, mentioned my concerns about the decline here and there, and worked hard to keep the cycling flame lit.

The new bicycle count report from PBOT (the first one they’ve published since 2014, unfortunately), forces me — and all of us — to fully reckon with these facts and speak out. Some folks say the report might have undercounted cyclists, and there is probably some truth to that (bicycle counting methods are notoriously flawed). But overall, the trend is real and it would be a grave mistake to keep our heads in the sand about it.

Cycling is too important to Portland for us to just sit back and hope things turn around.

As we continue to cover the decline and publish stories and content that push us forward, I want to share a list of theories I’ve heard and thought about thus far. Getting all this into the open is an important step, and I hope we can soon stop talking about why it happened, and start talking about what we will do to reverse the trend.

So buckle in. Below is my attempt at a full list of reasons why cycling has declined in Portland…

A socio-political-cultural shift

Too many of us took our cycling culture for granted. Between 2002 and 2012 or so, Portland had the greatest cycling culture in the world. No, we are not Amsterdam, but they can only dream of the bike culture we had (the head of bike planning for Copenhagen told me as much during my visit in 2013). It is no coincidence that our once-vaunted culture declined at the same time cycling rates began to plateau and then drop. (City Cast PDX podcast host Claudia Meza and I talked more about this in an episode that came out Tuesday.)

The hard truth is that Portland walked away from cycling around 2012. It’s a shift in culture that has troubled me for years. Some of the creative cultural elements — like the Sprockettes, BikeCrafters, and custom bike builders — waned because all cultural moments eventually fade away. But in Portland, we fanned the flames of this shift because city leaders and advocates began to lose confidence in cycling when it hit some tough times.

This doubt crept in around 2010 and the result was a new silence around cycling that is still happening today.

Remember when PBOT decided to change the name of “bicycle boulevards” to “neighborhood greenways”? Remember when PBOT embarked on the North Williams Avenue project in 2011? It was going to be called the Williams Bikeway Development Project. But they changed the name to Williams Avenue Traffic Safety and Operations Project. Or how about in 2016 when the nonprofit Bicycle Transportation Alliance changed their name to The Street Trust? Remember the Bike Commute Challenge? Now it’s called the Move More Challenge. Or the time in 2020 when City Council was poised to get re-educated on several key bike issues, then PBOT and Commissioner Chloe Eudaly got cold feet and removed the presentation from the agenda?

That presentation was scuttled because of one of the biggest reasons for the silence around cycling at City Hall and PBOT: That it’s too white and to prioritize it goes against the City’s new focus on racial equity. That’s a dangerous miscalculation. “Cycling” the noun definitely has some too-white problems (which I address below), but “cycling” the verb does not. That’s a distinction I don’t think enough local leaders understand or appreciate.

City Cast PDX host Claudia Meza and I talked about this in our conversation Tuesday (at around the 11 minute mark). “I feel like [the City is] just all about inclusivity and DEI [Diversity Equity and Inclusion] and all this stuff, but they are just not wrapping that around biking,” Meza said. “As a person of color who’s been in the Northwest for like over 20 years, cycling is not white.”

When you walk away from cycling due to misplaced fears about racial equity, you not only slow progress, you also erase all the people of color who love to ride bikes, who rely on it as a form of transportation, and who want it to be safer. And when you systematically erase cycling from your city, you should not be surprised when it disappears.

We also got complacent. For years Portland was adored by the media and the urban planning industrial complex. All that attention went to our heads and we lost our edge.

Now we’re in a chicken-or-egg scenario: We’ve lost our major cycling champions in City Hall and we have a PBOT work force that has lost confidence in cycling at the same time the culture has weakened; but we need a strong culture to (re)create those champions and get our City staffer swagger back.

The bike scene is still too white and too centrally located

Portland will never reach its potential until it reaches into every neighborhood in the city. I’m talking about both hard (concrete) and soft (cultural) infrastructure. We need safer streets near the Gresham border and the hills of southwest, and our advocacy organizing needs to go way beyond wealthy white people.

There are some great success stories here. There’s a vibrant, Spanish-speaking advocacy group in the Cully neighborhood and since the tragic murder of George Floyd by police officers and resulting protests, we’ve seen growth in local groups like Black Girls Do Bike, BikePOC PNW and others. But the struggle to expand the circle of bike activism beyond the usual suspects is still in its awkward tween years.

WTF WFH (Work From Home)

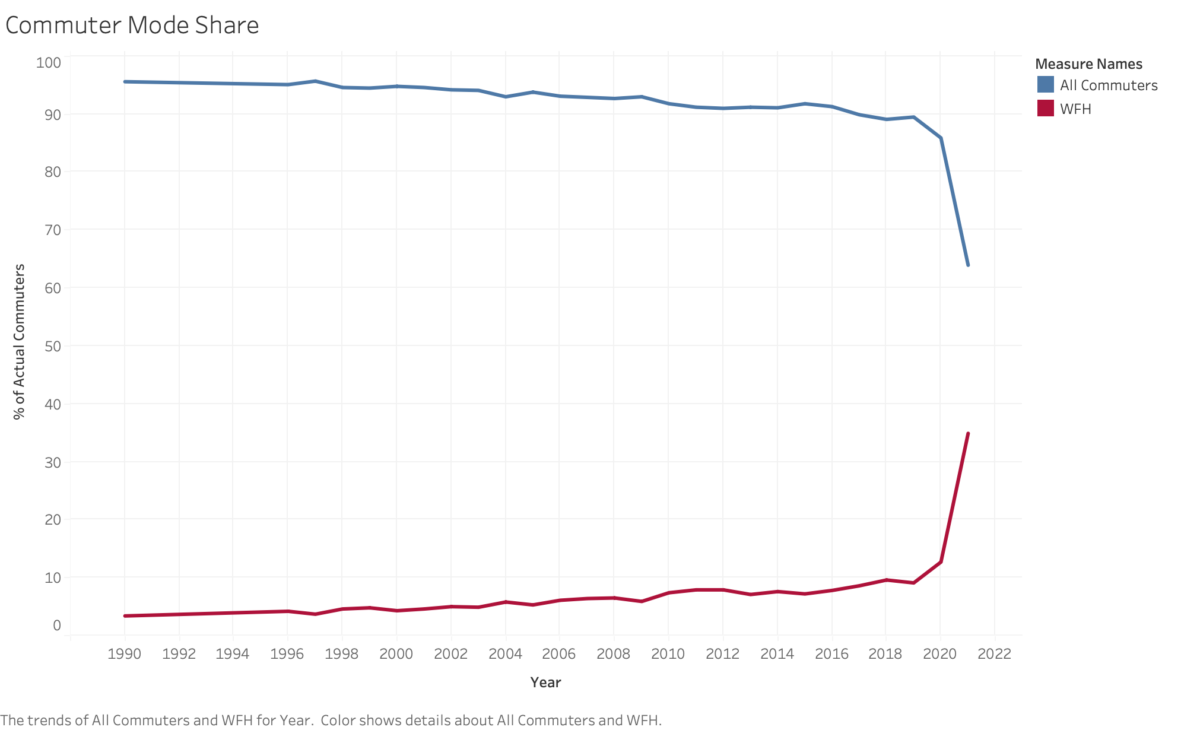

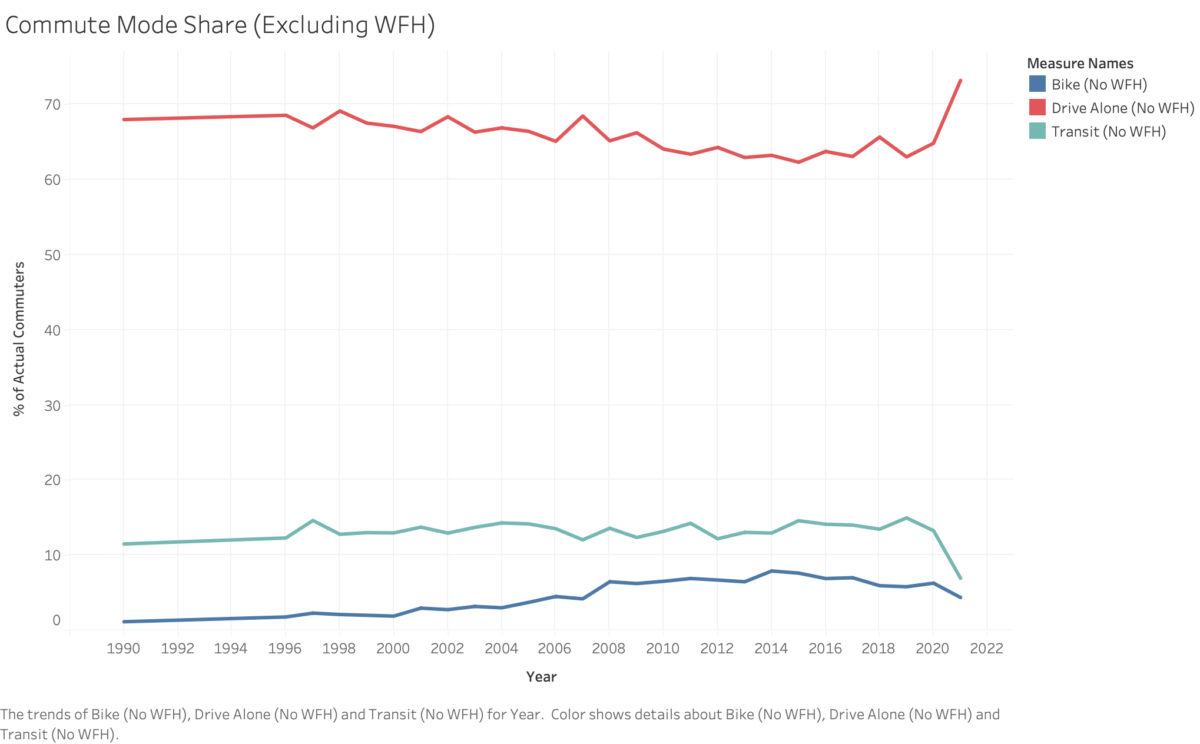

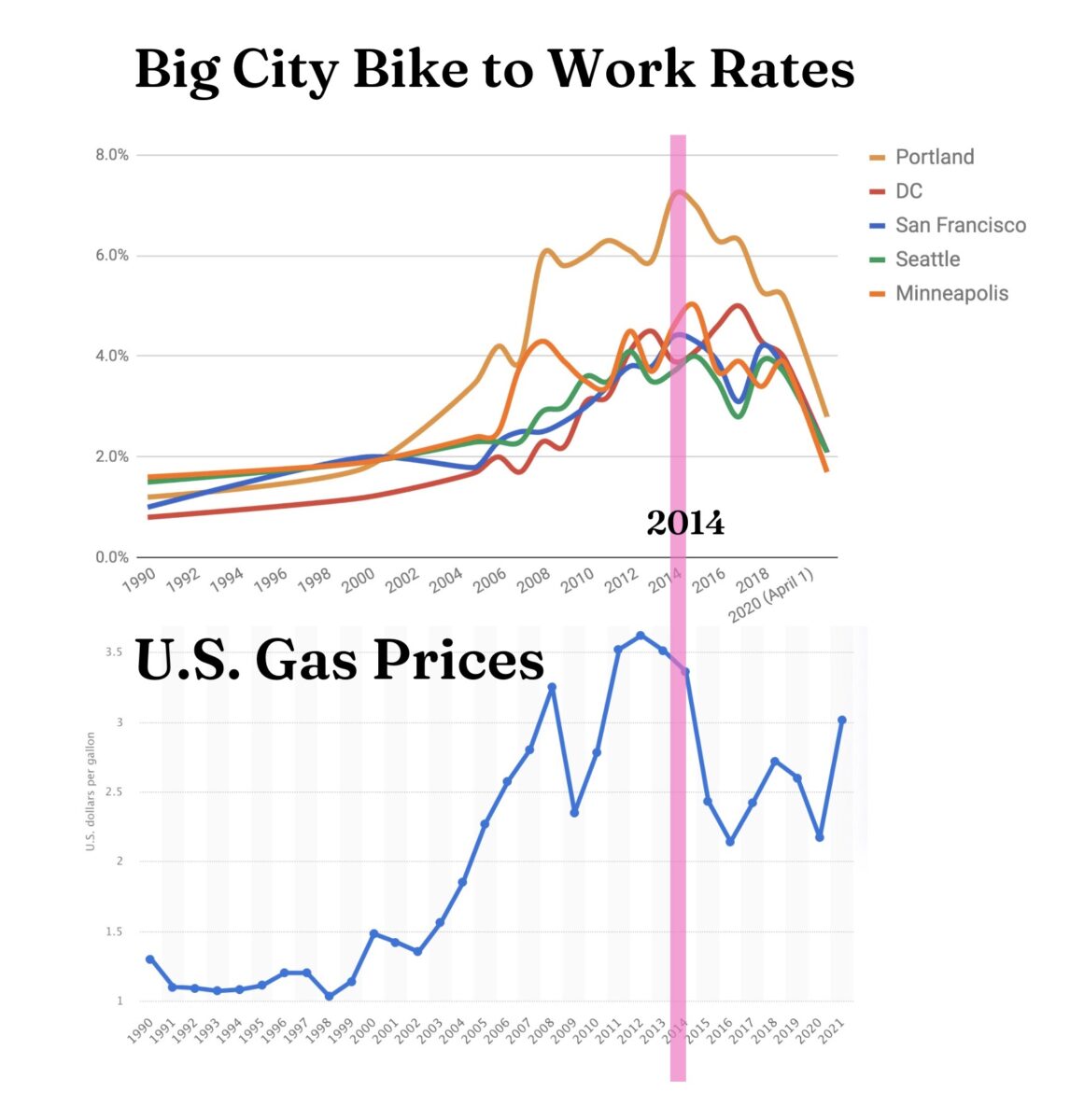

The work from home phenomenon is both powerful and recent, so a lot of people are talking about it. Recent U.S. Census data shows that Portlanders who work mostly from home spiked nearly fourfold between 2019 and 2021 — not surprising due to the pandemic (although the upward telecommute trend began in 2014).

WFH decimated commute trips and it had a disproportionate impact on bicycle riders (see charts above). When we look at Census numbers and take WFH folks out of the equation, there’s a big increase in drive-alone commuters and a related decrease in bike commuters. I’d surmise that this has a lot to do with the erosion of public safety, increased skepticism of strangers and general isolationism many people have taken to since the pandemic.

Before Covid, I recall city staff extolling the virtues of WFH as a welcome weapon against climate change and congestion. Now, as downtown struggles and no one wants to return to offices, they might be changing their tune.

Erosion of public safety

This is a big one. Another thing that started in 2014 was massive encampments of people living in tents along popular bike paths. Ever since those camps on the Springwater Corridor, and the decision by local leaders to not address it, I’ve heard from readers that they simply do not feel safe riding on multi-use paths. In 2016, we reported on the leader of a bike summer camp who cancelled their activities due to these fears. And by 2019, before the pandemic started, it reached a boiling point.

These paths were the lifeblood of many people’s riding habit. When they fell off the map due to these real and/or perceived issues, it was a massive loss.

Fear of bad interactions with people on paths is just one part of this. The general sense of lawlessness in public spaces brought on by rampant drug use and many people in need of mental health care, combined with the reluctance and/or inability of our government to do its job and keep people safe, has been a knockout blow.

Infrastructure & traffic safety fears

Way too many Portlanders are afraid to use our streets without a car, and I can’t blame them. Our infrastructure has not kept up with our rhetoric and people can only be disappointed so many times before they simply give up.

Our streets are filled with people on their phones, people who use massively oversized and dangerous vehicles for doing everyday things, people whose brains are hijacked by motonormativity, and people who have been told repeatedly by the Portland Police Bureau that they are not likely to get caught if they break traffic laws.

At the same time, our bike infrastructure is not nearly as good as folks in the Portland Building and City Hall think it is. PBOT Bike Coordinator Roger Geller recently said “Our strategy of ‘build it and they will come’ is just not working anymore.” That’s only half true. If we actually built excellent and connected bikeways and safe, welcoming streets, people would come (see this 2016 BikePortland op-ed, If we’re serious about cycling, let’s get serious about cycling infrastructure). Look what happens at Sunday Parkways: We tame drivers with redundant diversion and the presence of enforcement, and thousands of people walk and bike with joy and freedom.

We could have Sunday Parkways (in some places) every day, but too often we build projects that are politically safe instead of building truly safe streets.

It’s 2023 and Portland still does not have a single fully-protected, signal-prioritized, “8-80 safe” bike corridor that gets people from homes to destinations without a spike in fear.

Our bike network is full of gaps, we lack an effective maintenance strategy to keep them clean, and we still cater too much to drivers and the powerful voices who defend them. (We can return to 2014 for an example of this: We had a chance to install a bike lane along a popular commercial area of SE 28th, but after some business owners got in the City’s ear, PBOT scrapped the plan.)

I’ve been a broken record on this point: When it comes to street design and network connectivity, we are simply not doing enough to counter the rising threat of drivers and their cars. The gap between that threat and our anemic reaction to it is where people die and/or decide to drive.

We can’t only blame users of the system, we must also expect more from the architects of it.

The enforcement problem

Local transportation officials and advocates (I’ll include myself in this) have gotten enforcement wrong. It was right for us to be wary of the role of armed police officers in traffic stops, but the reflex to distance ourselves from enforcement entirely has left us in a bad place. As we sought to protect vulnerable people from police, we never communicated or implemented an alternative plan to enforce traffic laws.

The message was, “We don’t trust the police, so we are moving away from enforcement.” The message should have been, “We don’t trust the police, so here’s what we’re doing instead.”

The alternatives are right in front of us: automated enforcement cameras, bolder street designs that encourage safer driving, and a larger role for PBOT and non-armed civil servants to enforce some traffic laws. We’ve made some progress on all three, but not nearly enough.

Driving is too easy

It’s not enough to make incremental progress for cycling, we must simultaneously reverse progress for driving. As a driver myself, I would happily trade less convenience for a healthier, more humane city (which I did by supporting a diverter at the end of my block). PBOT has made some strides on this, but we must do more, and more quickly.

Currently there are numerous key cycling arteries that are dangerous only because of the presence of drivers and a lack of physical protection between their cars and bicycle riders. SE 7th, N Interstate, SE Foster, SE 122nd, NE Marine Drive, NE Lombard, SW Barbur Blvd — we could place concrete barriers on all those streets today and they’d be much more appealing to bike riders tomorrow.

We could also make driving much more expensive, but because Portland officials haven’t figured out how to decouple equity concerns from transportation planning efforts, we are still stuck in the mud. Higher gas taxes, EV charging fees, parking prices, congestion charges — there are a lot more ways to create revenue from our transportation system. We should try more of them.

Bike facility maintenance (and lack thereof)

It’s not actually a bike lane if it’s covered in debris, trash and/or a large puddle most of the time.

ODOT simply doesn’t care enough to keep bikeways on their roads clean and passable, and PBOT has cut funding for maintenance crews for years and has struggled to keep enough workers on the job. And with more protected bike lanes in the network, PBOT still hasn’t figured out how to sweep them efficiently.

Whatever the official excuse is, the amount of leaves, gravel, snow, mud, water, trash, cars, glass, and so on and so forth, is unacceptable. Neglected bikeways send a clear signal to the people: We don’t respect cycling and we don’t expect anyone to use these spaces. That signal has been heard and people have reacted accordingly.

Gas is too cheap

I know a few smart people who say the best way to predict cycling rates in the U.S. is to look at gas prices. The correlation between high gas prices and high bike ridership — and vice versa — has long been a solid argument. But I would posit that the correlation will weaken going forward in large part due to the forces I’ve laid out in this article. As people get even more fearful of others, inequity and selfishness grows, and as long as options to driving are not as attractive, most Americans will simply pay whatever it takes to keep driving.

Demographic forces

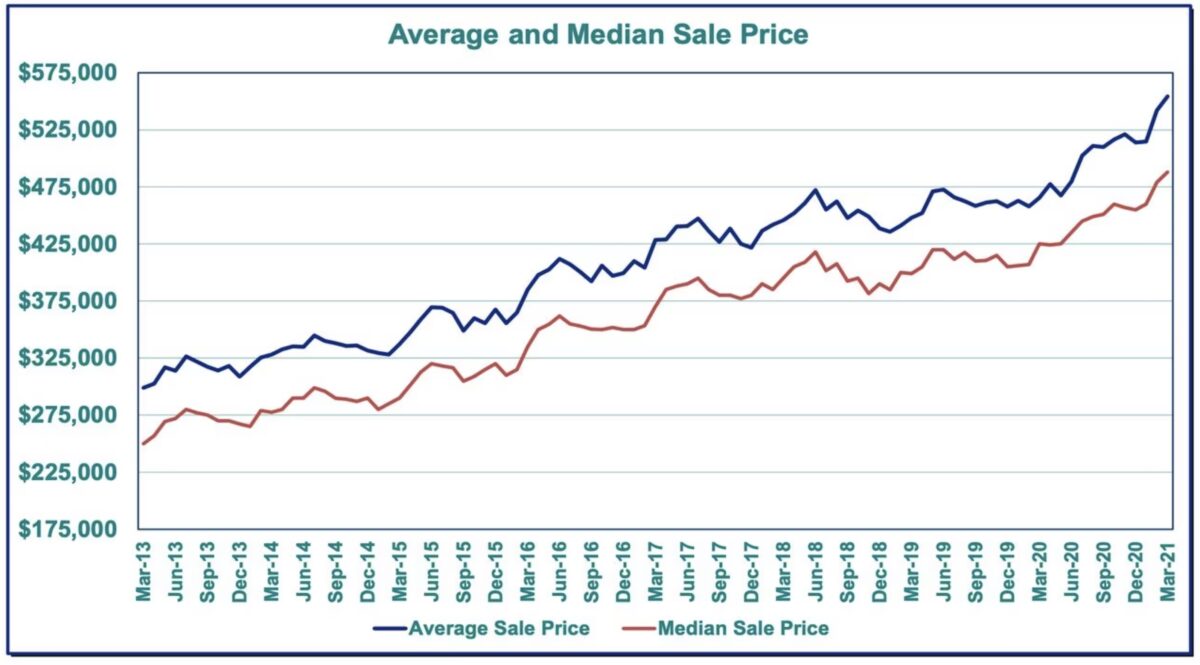

This topic is beyond my area of expertise (actually all of these are, but why stop now?!). I include it on this list because I’ve heard it brought up many times: The combination of new Portland residents moving here in droves around 2012, and higher housing prices brought on by a lack of supply, has forced younger, lower-income people out of the most bikeable inner neighborhoods and into less-bikeable ones. This was a double-whammy because those bike-oriented people now have longer trips and less safe infrastructure to ride on; while those new residents have more money and are less likely to have cycling play a large role in their everyday life.

Those younger residents that helped create the fertile comedy grounds that the hit show Portlandia germinated from, had less money, but they also had fewer life responsibilities (no mortgage, no kids, and jobs that fit their lifestyle) and more time to create, organize, and advocate around cycling. When they grew up and left, they were replaced by folks who had a different relationship to Portland and to cycling.

The local advocacy ecosystem

In 2014, two years before the BTA changed their name to The Street Trust, there was already talk about how the group had stopped being a loud voice for cycling in Portland. In a comment to a BikePortland story that was part of a series intended to help us break through the stagnation, the co-founder of then-BTA, Rex Burkholder, couldn’t stay quiet any longer. He felt the organization had lost their voice and wrote, “It’s time for the BTA to return to its roots, or step aside.”

One week after that comment, we reported on how the BTA had made an intentional shift in strategy to move way from bicycling and toward something they felt would be more appealing to business interests and suburban partners. The BTA changed their name to The Street Trust two years later and has drifted further away from cycling ever since. Two weeks after we reported on the BTA’s shift, activists saw the writing on the wall and launched Bike Loud PDX. That group has been growing ever since, but still has no paid staff and doesn’t have the resources or legacy to wield major influence.

The BTA was a force to be reckoned with in its early years. Today, The Street Trust continues that legacy, still does vital advocacy work, and celebrated their 30th anniversary last year — but their shift away from cycling has come at a cost. One source inside City Hall told me this week that, “Bike advocates have no presence or political capital in city hall at the moment.”

It’s also notable to me that The Street Trust hasn’t made any statement about the counts report or the decline in cycling since it was released over two weeks ago.

Another element of this topic (unrelated to The Street Trust) is the demoralization of many bike activists. The past decade has been tough on Portland’s legendary bike advocacy volunteer troops. From the lack of urgency on the 2030 Bike Plan, to the myriad decisions where Portland leaders followed the path of least resistance instead of sticking to our velo-centric values, some activists just got fed up and moved on.

Bike theft

The bike theft problem has plagued Portland for a very long time. And it persists, despite our best efforts to do something about it. Regardless of stolen bike statistics, many people simply don’t think their bike will be secure if it’s locked-up outside. Heck, thieves even target locked bike storage rooms in apartment and condo complexes! Until we reverse the perception around this issue and are able to show that the City of Portland is making a sustained effort to remedy the problem (similar to the effort they’re making for stolen cars), it will continue to dampen enthusiasm for cycling.

The rise of carsharing and micromobility

Remember when Uber and their drivers forced their way onto Portland streets, despite not having a permit? When Uber and Lyft burst onto the scene, they likely ate up some bike trips and might have gobbled up some on-the-fence bike riders. And other types of non-car vehicles have also gained a toehold in the bike lanes in recent years. E-scooters, one-wheels, and e-unicycles have all contributed to the erosion of the cycling habit for some Portlanders.

So now what?

We need to continue to learn and share information, then we need to use that knowledge to course-correct and get back on track. For my part, I’ve been soaking up perspectives and feedback since the count report came out two weeks ago. We’ve published several stories about it, I’ve done two podcasts so far (ours and I was on the City Cast PDX pod Tuesday), and tonight (Weds, 4/5) we kick-off a new Bike Talk Happy Hour event we co-organized with three businesses on SE Ankeny and 28th.

Everyone has a role in this rebuilding process. Getting mad and pointing fingers is helpful only up to a point, then it becomes detrimental.

I believe Portland is “The City That Works… Better With Bikes.” If you believe that too, let’s work together. I don’t want to return to the “old days.” I want us to build something that reflects lessons learned in the past decade and that is even more exciting and beautiful than we could have ever imagined.

If anyone wants to talk about this, I’ll be at Gorges Beer Co on SE Ankeny just before 28th from 3-6 pm. Come join us at the inaugural Bike Talk Happy Hour.