(Photos: J. Maus/BikePortland)

When BikePortland reported last week that the city may slash its goal for increasing biking, the eighth paragraph contained a twist.

The obstacle to advancing our city to 25 percent of trips by bike by 2030 wasn’t actually the biking, city staff said. It was real estate.

“Even in 2035, there are too few jobs too far from housing,” senior transportation planner Peter Hurley had told the city planning commission June 13.

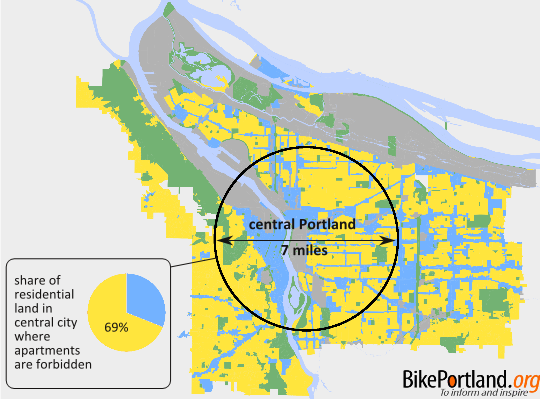

In other words: Portland wants to officially concede that its recently approved comprehensive plan didn’t legalize enough density for Portland to join the ranks of the world’s best cities for biking.

In a sense, this is no surprise. As anyone familiar with Utrecht, Copenhagen, Montreal or Hangzhou could tell you, the single biggest difference between the design of those cities and Portland isn’t the continuous networks of protected bike lanes, paths and low-stress side streets (crucial though those are). It’s the buildings everyone is going to and from.

As Elly Blue wrote on this site 10 years ago, density creates proximity — both by making it legal for more homes to exist close to jobs and by making it legal for more homes to exist close to every single retail storefront, which in turn makes it possible for crucial retailers like grocers to pack more tightly together, reducing the average distance to reach one.

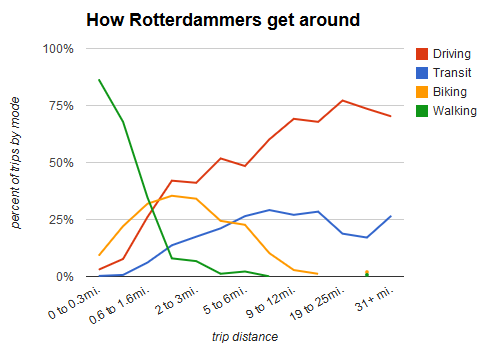

In 2014, we looked at Dutch travel habits to show that even in the world’s best country for biking, most people drive for trips of more than three and a half miles. The crucial difference is that in Dutch cities, trips of less than three and a half miles are far, far more common, thanks to Dutch density.

This is the phenomenon Hurley described in June. Even 13 years from now, too many Portlanders will have to frequently go more than a few miles to get where they’re going.

In part, that’s because most of Portland’s buildings didn’t have the advantage of being built before people used cars. But it’s also in part because city laws make it illegal for Portland to look anything like Utrecht.

Also in 2014, local wonks Nick Falbo and Elliot Akwai-Scott used Google Sheets to create an ingenious online game that challenged Portlanders to bring the citywide biking rate to 25 percent. What most people found, upon playing, was that it was extremely difficult without much-larger-than-planned changes in where people lived.

“Is is realistic to even think we can reach a mode share that high?” Falbo — who is usually anything but cynical — asked at the time.

Advertisement

Portland’s ability to keep building homes depends on its willingness to live without parking spaces

Rendering: Myhre Group Architects via Portland Bureau of Development Services.

Some people will say that Portland already seems to be getting denser, and that the city’s latest zoning plan will let this continue. They’d be right. Thanks to the post-recession surge of people interested in urban living, parts of the city have been getting substantially denser.

Biking, transit and carsharing have become the city’s best hope for creating new, denser housing and keeping both old and new housing affordable.

This seems to be working. It’s almost certain that a lot of the 5,000 new bike commuters Portland added in 2014 had something to do with the 5,000 new apartments that had opened for leasing across the city in the previous two years.

Also significant: many of those new buildings were constructed with zero on-site parking, the first apartments in decades to be built that way.

And that’s the other half of Portland’s current situation: biking, transit and carsharing have become the city’s best hope for creating new, denser housing and keeping both old and new housing affordable. That’s because these are the transportation modes that make on-site parking unnecessary in new buildings — and on-site parking has turned out to be a crucial tipping point for Portland’s development industry.

The biggest thing going on right now in Portland housing development is that even as thousands of new apartments are being constructed, almost none are currently being designed. The number of large residential buildings being newly proposed fell to almost zero six months ago Tuesday: Feb. 1, the first day that Portland’s inclusionary housing ordinance took effect.

No new buildings in the pipeline means that unless something changes (either in the law or in how buildings get designed and financed), Portland’s housing shortage and further rent hikes are on track to return with a vengeance in approximately 2020.

The inclusionary housing law requires new buildings of 20 homes or more to offer 10 to 20 percent of their homes to lower-income people for less than market rate, essentially paid for with various offsetting subsidies. But if those offsets are too small and almost nothing gets built, the law could backfire — not only would few market-rate homes be built, few below-market-rate homes would be, either.

Almost every developer in Portland is currently convinced that the inclusionary housing law is out of balance. By their estimates, either the mandate is too big or the offsets are too small. If they thought differently, they’d still be adding projects to the pipeline.

But one developer has actually been thinking differently. He’s Dennis Sackhoff (who Battlestar Galactica fans may be interested to know is Starbuck’s dad), a former suburban tract developer whose company, Urban Development Group, has found a niche in the city: apartments with relatively few amenities and no on-site parking. For example, UDG is behind the new Alexander on East Burnside:

Love or hate their buildings — and some have been less than beautiful — Urban Development Group seems to be the only developer in town that’s enthusiastic about the new inclusionary housing rule, for one key reason: one of the offsetting incentives is a waiver of the city’s on-site parking requirements for buildings near frequent transit lines.

Most developers are still looking to include on-site car parking, in part because most of the city isn’t close enough to good transit. But UDG has been able to build without parking, which means the inclusionary housing offsets it’s able to take advantage of are bigger than the ones other developers are getting. In fact, UDG is so enthusiastic about the new rules that it’s been rifling through its backlog of projects designed before Feb. 1 — ones that are exempt from the affordability rule — and voluntarily opting into the program so they can get out of the parking requirement.

- At 2548 SE Ankeny St., a planned 77-home building with about 26 parking spaces and no homes below market rate is set to become a building with 81 market-rate homes, 15 below-market-rate homes and no on-site parking.

- At 316 NE 28th Ave., a planned 74-home building with about 25 parking spaces and no homes below market rate is set to become a building with 101 market-rate homes, 18 below-market-rate homes and no on-site parking.

- At 2789 NE Halsey St, a planned 30-home building with no parking spaces and no homes below market rate is set to become a building with 45 market-rate homes, eight below-market-rate homes and no on-site parking.

- UDG is also asking to convert a trio of projects in Sellwood and Moreland from 187 homes with 55 parking spaces and nothing below market rate to 175 market-rate homes, 35 below-market-rate homes and no parking.

Assuming they’re built, will these buildings turn out to be profitable? Only if people want to live in neighborhoods that are almost certain to become much more crowded with on-street cars.

In other words, these buildings will only work, and other developers will only be able to copy UDG’s template, if the residents are taking most of their trips with something other than a car.

How to weigh in on housing

Fortunately for Portlanders who want to shape the future, the city is in the midst of several different projects that could greatly affect proximity and affordability in the years to come. Last week, the city’s planning bureau sent an email plugging this useful website summarizing them.

The city has five different projects going, all at different levels of completion:

- The “residential infill project” focuses on re-legalizing duplexes, triplexes, cottages and internal home divisions in lower-density residential zones, while also reducing the maximum size of buildings in those zones to reduce demolitions and McMansions.

- The “better housing by design” project focuses on tweaking rules for higher-density residential to balance open space, parking and setback requirements against the need to hold down housing prices.

- The “Southwest Corridor equitable housing strategy” focuses on adding below-market-rate homes along a possible future Barbur Boulevard rail line.

- The “design overlay zone amendment project” focuses on setting more objective standards for design of new buildings so fewer projects will pile up debt while they wait more than a year for approval by a volunteer panel.

- “Inclusionary zoning,” discussed above, aims to create more below-market-rate homes by requiring them in new buildings and providing offsetting subsidies.

You can follow the links to learn more, sign up for notices about each project, or get in touch with their project managers to share your thoughts.

(Disclosure: I work a few hours a week as a writer for Portland for Everyone, an advocacy campaign for abundant, diverse, affordable housing in Portland. But I don’t speak for it here — this analysis is my own.)

— Michael Andersen, @andersem on Twitter

Never miss a story. Receive our daily headlines via email.

BikePortland needs your support.