The Oregon Department of Transportation says it needs to preserve five auto lanes on 82nd so the dramatically increased number of cars that Metro expects on the street by the year 2035 will have somewhere to sit during rush hour.

Should a new high-capacity express bus line through Southeast Portland run on the most important street in Southeast Portland, or 30 blocks away?

The question seems odd. But as Metro and TriMet ask the region whether the new “bus rapid transit” line they’re planning should run on half a mile of 82nd Avenue, here’s part of the subtext: In order to get permission to run the bus line on 82nd Avenue, project planners have agreed not to aspire to do anything for biking, walking or transit on 82nd that might significantly reduce the number or capacity of cars there.

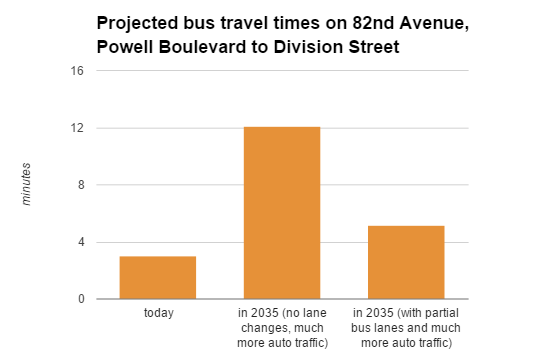

In fact, even if the highest-quality version of the project currently being considered were built, buses there are projected to travel slightly slower in 2035 than they do now. Rush-hour travel times would rise to about four to five minutes for the half-mile stretch, up from about three minutes during the afternoon peak today.

Among other factors, this is because the Oregon Department of Transportation says it needs to preserve five auto lanes on 82nd so the dramatically increased number of cars that Metro expects on the street by the year 2035 will have somewhere to sit during rush hour.

In this scenario, the major time benefits of the project to bus travel on 82nd Avenue would materialize only if the street becomes overwhelmingly jammed with cars over the next 20 years — which is what the official models currently expect to happen, despite the city and county’s official goals of cutting local auto traffic in half over the next 15 years.

Here’s why the project might be a good idea anyway: If it is not built, and if Portland does indeed fail to meet its goal of halving auto trips by 2030, then bus travel times on this stretch of 82nd will triple.

That’s because the hundreds of people in 82nd Avenue’s crowded buses would be stuck behind hundreds of single-occupancy cars — just like all the people in cars would be.

TriMet has 21 months to find funding and consensus

It’s important to note that this range of possibilities is not written in stone. Instead, this is a rare look into the pre-planning that goes on behind the scenes of every big transit project.

With this project, a quirk in the public process is opening a bit of that pre-planning to more public debate than usual.

At issue right now is a small portion of the 18-mile project: the 1/2 mile between Powell Boulevard and Division Street in mid-Southeast Portland.

The Powell-Division Transit and Development Project is a proposal from transit agency TriMet and regional government Metro to spend something like $200 million, half of it from the federal Small Starts grant program and the other half from undetermined local sources, to create an express line of big bending buses featuring flashy new stations with raised platforms and other features that make traveling by bus feel more like traveling by MAX.

Unlike MAX, however, the buses will mostly not get lanes of their own. Instead they’re expected to get, at most, a series of chances to jump ahead of cars at stoplights. To support this, some blocks would get bus-only turn lanes and others would have lanes that would at least theoretically ban cars that are not preparing to turn right.

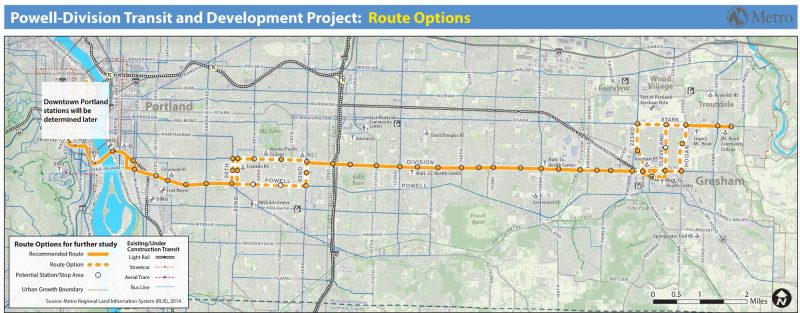

The full route would run between downtown Portland and downtown Gresham. It’d probably start on the south Transit Mall, cross Tilikum Crossing and join Powell through inner Southeast Portland. Between Powell and Division, the route will have to jog northward. That’d happen either at 50th Avenue, 52nd Avenue or 82nd Avenue.

Of those three, the likeliest prospect is 82nd Avenue, a state-run five-lane highway that doubles as a main street for much of Southeast Portland. It already carries one of TriMet’s most-ridden bus lines, the 72; the new express bus line might also run on that stretch.

(Map: Metro)

TriMet started applying for federal funds last May. It has until Oct. 2, 2017, to come up with a detailed plan for the route and a general sketch of how to pay for everything, including the new buses, stations, road work and all the associated planning efforts.

On March 28, the project’s steering committee is expected to choose a final route, including the decision of whether to run the big buses on 82nd. From there it’ll go to Metro, to the cities of Portland and Gresham and to other relevant agencies. If all goes well for the project, it’d open in September 2020.

For project managers, this is the moment they’re hoping to get buy-in from people who care about 82nd Avenue.

“There are a lot of attractions there; it works for the community,” Metro planner Elizabeth Mros-O’Hara said Jan. 8. “But they need to see what it’s going to look like enough to understand what the potential impacts might be.”

‘Every little bit counts for transit’

Though they won’t get full lanes of their own on 82nd, the new buses would use digital communications with stoplights on the route to get traffic signal priority.

“It’ll say ‘Hey I’m coming! Stay green,’ or it’ll say ‘Hey I’m coming! Shorten that red and go green,'” said James McGrath, a project consultant for CH2M. “We’re using station placement to garner little advantages. … Every little bit counts for transit.”

McGrath is hoping that the buses, each of which would have room for something like 86 people, will be allowed to load and unload passengers right in their lane rather than pulling over and waiting for a gap between cars to get moving again. But McGrath said that’ll only be “possible” if having buses stopped in the right-hand lane isn’t expected to greatly slow auto traffic.

“If we’re allowed, if the traffic modeling shows that it’s possible, the bus will stay in the travel lane as opposed to pull out,” McGrath said.

On their approach to busy intersections, buses would get either a short left-turn lane or a right-turn lane that can also be used by cars turning right into a driveway.

And at the corner of 82nd and Division, the new buses might get a new diagonal stretch of road to skip the stoplight completely.

All of that together, project planners said, adds up to quite a bit of travel time savings for people in buses — almost as much time as dedicated lanes would save, they said. But the planners couldn’t say precisely what difference dedicated lanes would make, because the project has not bothered to calculate them. That’s how far off the table dedicated bus lanes are.

TriMet has also not yet estimated what the travel times will be in the year 2020, when the project first opens.

At some intersections, McGrath said, the stoplight changes might add up to travel time savings for people driving.

Because so little road work is anticipated, the whole thing comes out to quite a bargain compared to a new transit line that would have new dedicated space. TriMet’s Orange MAX Line that opened last year cost about $200 million per mile. The entire 18-mile Powell-Division project, by contrast, is aiming for $200 million total, half of it from local money that has yet to be identified.

For comparison’s sake, a bike lane protected by concrete or hardened plastic bumps costs about $50,000 per mile, but only if it can be put on road space currently used for something else.

‘We have to try to make things better for everybody’

I asked the four public transit planners assembled at the Jan. 8 meeting what the problem would be with slowing auto traffic if it were to significantly improve public transit.

After a moment Jeff Owen, TriMet’s active transportation coordinator, answered.

“We have to consider all modes and all users.”

– Don Hamilton, ODOT on why the agency won’t consider full bus lanes on 82nd

“Our partners,” he said, referring to the state and city governments. “We can’t really do that much alone.”

The city didn’t have anyone at the meeting, but ODOT spokesman Don Hamilton was there. As the other people in the room waited for him to say something, he answered my question too.

“Because we look out for all users of the corridor,” he said. “We have to try to make things better for everybody.”

Even if that’s in the service of using devices that are destroying our planet and killing 30,000 Americans a year, I asked?

Those are larger problems beyond ODOT’s control, Hamilton replied.

Later, I asked Hamilton to clarify if “make things better for everybody” literally meant that ODOT couldn’t support any transit project that would increase auto travel times.

Hamilton said he hadn’t meant that.

“I meant that more generically, that we have to consider all modes and all users,” he said.

No bike lanes without more money, TriMet says

OK, so what about bikes?

Last month, Jonathan wrote about the unexpectedly tense meeting between the project staff and the Portland Bicycle Advisory Committee at which TriMet staffers tried to talk down the possibility of continuous bike lanes on this stretch of 82nd.

Officially, the project is considering what it describes as the “high-impact” scenario of putting continuous bike lanes on 82nd. There’s also a possibility that some compromises could be found between that scenario and the “minimum impact” one that has no bike lanes — a short bike lane might be added to improve a crossing or connect to a particular bus station, for example.

But after looking at this in detail and asking quite a few questions, I have to agree that it would be difficult for this project to include bike lanes. Here’s why.

“I think the reality is a lot of this area would have parallel bikeways.”

— TriMet active transportation planner Jeff Owen on bike access to 82nd

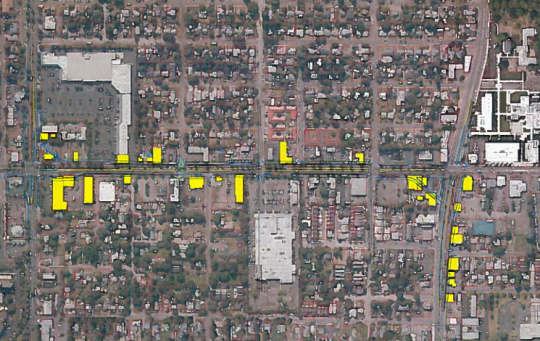

82nd Avenue currently has two auto lanes in each direction plus a center turn lane. Installing bike lanes as part of this project would require, more or less, one of these three things:

1) You could widen the roadway, which would force TriMet to buy and demolish various buildings. Much of the property facing 82nd is currently parking lot, but not all. If the acquisition were split evenly on both sides of the roadway (which would preserve the existing trees on both sides) this would require some level of demolition or relocation of buildings on properties. Metro and TriMet haven’t done any research into what this would cost except to say that they don’t think the project can afford it at its current scale.

2) You could have auto and bus traffic share a single lane in each direction with a center turn lane. This would make 82nd Avenue much easier to cross and open up room for wider sidewalks, but would greatly increase bus travel times.

3) You could remove the center turn lane and use a curb to block left turns. McGrath said this would require new space for U-turns at Division and Powell and probably also at Woodward, where Asian superstore Fubonn anchors a major strip mall. He said that tapering the lanes to allow those U-turns wouldn’t end up saving much space along the corridor; you’d still end up buying a lot of land and demolishing a lot of buildings.

Since none of these options have much appeal without significantly more money than the project expects to have, the project staff is convinced that the next best alternative is for the city to create a new neighborhood greenway on 79th and then make it easy to get over to 82nd here and there.

“I think the reality is a lot of this area would have parallel bikeways,” said Owen.

It’s possible to argue that half a mile of bike lanes on 82nd Avenue isn’t a big deal, since the rest of the street will still lack them. But there’s another side to that coin: If the project is built without bike lanes, will people spend the next 50 years saying there is no point putting bike lanes on 82nd at all, because this crucial segment won’t have them?

One possible answer to this is that as these properties gradually redevelop along 82nd, the City of Portland could require each developer to set aside enough space beside the road for both a sidewalk and a new bike lane. That would take decades, but it might work. The city currently has no such requirement.

As I’ve put this story together I’ve talked to quite a few people about the Powell-Divison project, and most people seem to have genuinely mixed feelings about it. We’ll cover those more as the project moves forward — and in the coming days we’ll also have a piece looking closer at plans for the 70s Bikeway that’s proposed on 79th Avenue.

— Michael Andersen, (503) 333-7824 – michael@bikeportland.org

BikePortland can’t survive without paid subscribers. Please sign up today.

Corrections: An earlier version of this post misstated the date of a meeting between BikePortland and various project officials. It was Jan. 8. It also misstated the passenger capacity of the bending buses (it’s 86) and the west terminus of the new line (probably the north transit mall, not the south transit mall).