In Wednesday’s StreetsPDX post, I covered the features of its new website, its flow, tools, and the information about city code and policies it brings together in one location. StreetsPDX project manager Mathew Berkow presented the project last month to the transportation committee of southwest Portland’s soon-to-be-defunct coalition of neighborhood associations, SWNI (Southwest Neighborhoods Inc).

Today, I want to follow up on that post and share a bit of the conversation that happened after Berkow’s presentation, between Kurt Kruger, Portland’s new public works permitting czar, and a few experienced transportation advocates. Kruger’s group decides what public works, like sidewalks or bike lanes, the city will require a new development to build in the right-of-way.

Why is this exchange important? Because it got to the heart of what I’m hearing from every transportation advocate in the region, including most BikePortland commenters. Folks do not want same ol’ same ol’. The status quo is not acceptable. And the SWNI committee was no different, it seemed like they were expecting something more or different from StreetsPDX.

One participant asked, “I know that your goal is to create this comprehensive thing that makes decision-making clear and transparent for people. But, what’s the larger goal, is the larger goal to make the city better? Is there not a larger goal?”

Another participant, Don Baack, began with colorful language, mentioned “punching the card,” and ended with, “it is totally disgusting that we can’t figure out reasonable ways to solve problems that are very clear to most people on the ground.”

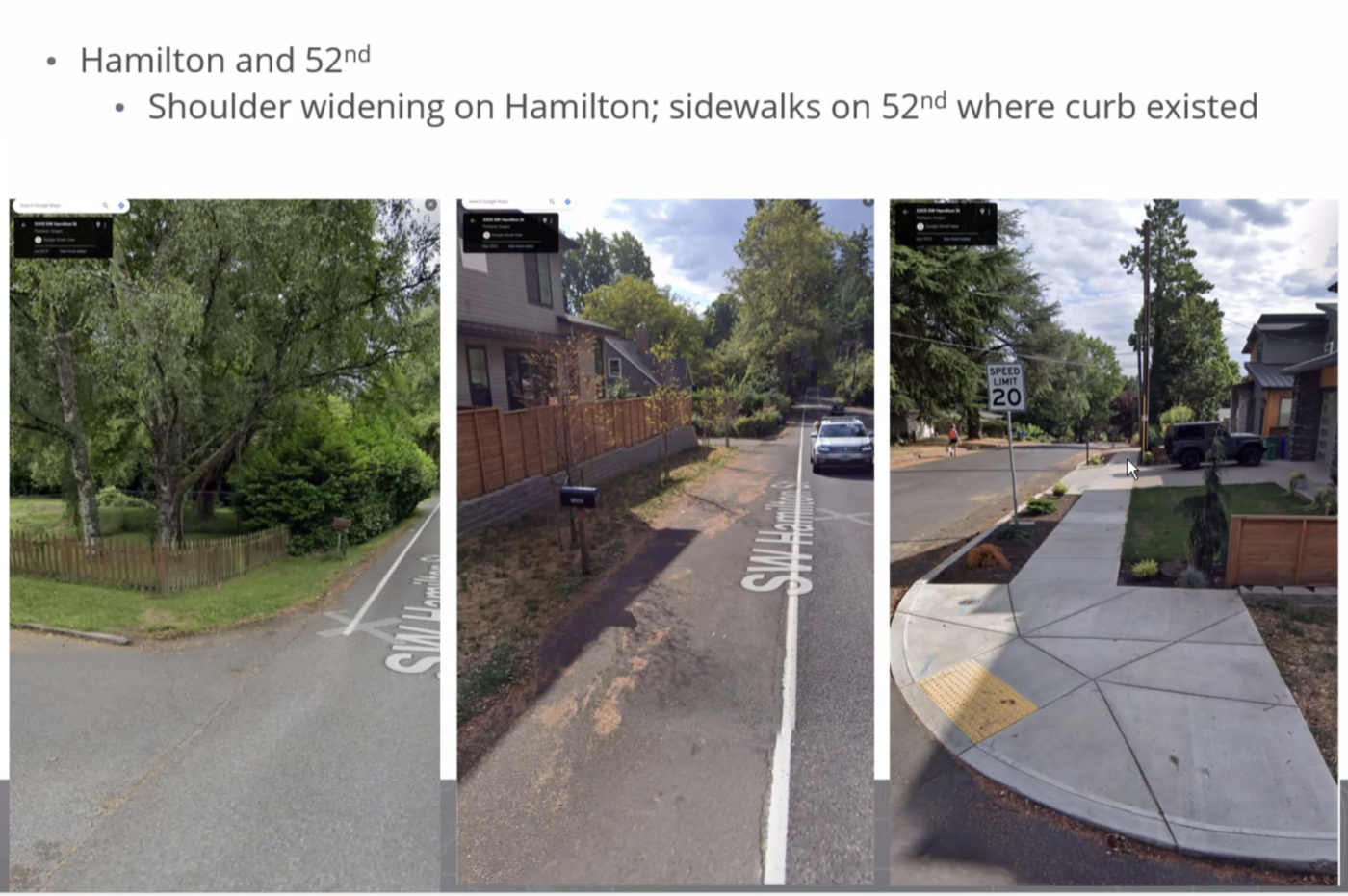

Keep in mind that the goal of StreetsPDX is to make a decision framework for how to allocate space in the right-of-way. And that’s good, it’s needed. But basically, it’s a guide to the inside of the box — way-finding for today’s status quo. Southwest’s problem is that it always ends up on the “How to deviate from standard improvements” pathway, which inevitably leads to shoulder widening, and pedestrians walking in the street protected by a stripe of white paint (see photos above and below). And also with the most incomplete bike network in the city.

Several minutes into the tense discussion between the transportation committee and Kruger, Marianne Fitzgerald asked a question which pivoted the conversation, and I heard something new from Kurt Kruger, for me at least. A glimmer of a suggestion of a way forward, at least in southwest Portland, and maybe in some other locations too. Here’s the exchange:

Fitzgerald, neighborhood advocate:

How can we help you work together to try to dream about how to get there, do as much as we can to hold developers accountable for the infill … How can we work together for the designs, the dream, and then push for funding to get the network built?

Kruger, City of Portland:

I appreciate that Marianne, I’ll say that I probably got uninvited to town center [West Portland Town Center] meetings because I kept saying, ‘Please don’t give us the same lack of tools that go with the up-zoning of the town center.’ Because I don’t want to be having this conversation with Marianne, or Marianne’s kids, or grandkids — however long I keep working here — because the tools are not effective, they are not delivering solutions. And it’s a tough nut to crack.

So I’m going to suggest: please keep advocating. If the advocation is, ‘prioritize the top five streets in SWNI’s umbrella’ — [then] really we need street plans, we need to land where those improvements should be, what they should look like. And it has to be sort of granular, it needs to recognize certain pieces.

Multnomah Blvd, for example, is going through Multnomah Village. That’s a different construct than it is near the post office. And so a street plan would take in all those different pieces as a roadway travels through different topographies and watersheds.

And so, having a contextual street design gives us that tool that we can point to with a developer. And why do I say keep advocating? Because every advocate out there, you’ve got an equally, if not louder, voice than a developer in city council’s ear advocating for their piece. And they are not mutually aligned. I’ll just say it that way.

That was the first time I heard Kruger mention corridor-length plans. Mind you, they would just be required frontage improvements for future development, and thus decades away from delivering a complete pedestrian or bike network, if ever. But still, it was a faint light at the end of the tunnel, and the only time I have heard any city official acknowledge that there is a growing problem in the southwest that is going completely unaddressed.

Let me parse Kruger’s comment a little: Currently, development review looks at required frontage improvements in a piecemeal way, one development at a time. This is a lousy way to get a sidewalk or bike network built.

Much of the planned West Portland Town Center (WPTC) area, like the rest of southwest Portland, doesn’t have formal stormwater facilities so runoff water drains to streams. Because the city has no money to build stormwater facilities, and they don’t feel they can legally make developers build the stormwater system that runoff from a sidewalk requires, the city planned for a two-phased development of the Town Center. The first phase up-zones properties that already have adequate stormwater infrastructure in anticipation of a second phase, in which there is somehow capital to build stormwater facilities for the remaining properties.

This is the same build-and-hope approach that has landed southwest Portland the infamous distinction of having the worst sidewalk coverage in the city.

When Kruger says that “contextual street design” gives him a tool “with a developer,” he is referring to the legal requirement that a city proportionately, appropriately and consistently apply its frontage requirements. (Known as Nollan/Dolan jurisprudence, the U.S. Supreme Court imposed limits on how and how much a government could exact from a developer for public works.) A pre-existing corridor-length plan allows the city to justify a frontage exaction as being consistently required of all developments, thus shielding it from developer claims of unfairness and consequent lawsuits.

And that’s a peek at the insider baseball of land use and transportation. Kruger’s answer wasn’t a home run, but it seemed like a step in the right direction. And it is a good idea to periodically touch base with what Kruger is thinking.