Summer vacation is coming to an end and the start of school for kids K-12 kids in Portland is just around the corner. In an ostensible effort to help children safely walk, bike and roll to school this upcoming academic year, Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler made an emergency declaration to ban unhoused people from camping along city-identified key walking routes to Portland’s K-12 schools.

Since the Portland Bureau of Transportation has identified these routes for more than 100 schools across the city, there are now a lot more places around the city where unhoused Portlanders can’t legally camp. As soon as The Oregonian broke the story yesterday afternoon, some transportation advocates denounced the restriction as needlessly harmful to people experiencing homelessness in Portland and expressed skepticism that it is in fact the best way to help kids get to school safely.

The emergency declaration cites “trash, tents in the right-of-way, biohazards and hypodermic needles” as potentially dangerous hazards preventing school-age children from being able to safely walk, bike and ride buses to and from school. It will “prohibit camping around school buildings and along priority routes to and from schools” and “prioritizes the work of the Impact Reduction Program to post and remove camps in these areas, and enables them to keep these sites free of camping with no right of return.” According to the declaration, this ban is effective immediately and will be in place until the end of August, but may be renewed.

This new camping ban is an addition to an emergency order Wheeler issued in February banning homeless camping along Portland’s ‘high crash corridors,’ which came after the Portland Bureau of Transportation released its 2021 traffic crash report that showed unhoused people in Portland are disproportionately victimized by traffic violence. This declaration was not well-received by local homeless and transportation advocates.

People who have experienced homelessness and advocates point out that when unhoused people are banned from camping in certain areas and their campsites – and all their belongings – are removed, they are often left without a place to go. With this many places throughout the city now on the list of prohibited camping spots, it’s certain a lot of people will be displaced. The declaration states the city will handle this by increasing shelter capacity, but even if there was enough room, not everyone feels comfortable staying in sanctioned shelter locations. Many people will simply start over at other campsites around the city.

“Removing houseless encampments along all school routes is not on the long list of initiatives that would improve safety for children. There are a lot of other ways to care about children’s safety and experience walking to school.”

– Sam Balto, teacher and safe routes to school activist

Though some homeless Portlanders have set up camps along school walking routes around the city, it’s not evident this poses an inherent risk to children walking to and from school, and Wheeler didn’t provide any explicit examples of such a risk in the declaration. Children are very vulnerable to traffic violence, however, and kids have been tragically injured or killed after getting hit by car drivers while walking to school. In 2018 and 2019, two students at Harriet Tubman Middle School were hit and injured by drivers within a few months, and in 2020, an 11-year-old boy was killed by a driver while walking to school in Gresham.

National Safe Routes to School advocates cite traffic danger as the top reasons kids might be unsafe traveling to school via active transportation. They propose transportation infrastructure investments and community education to improve safety.

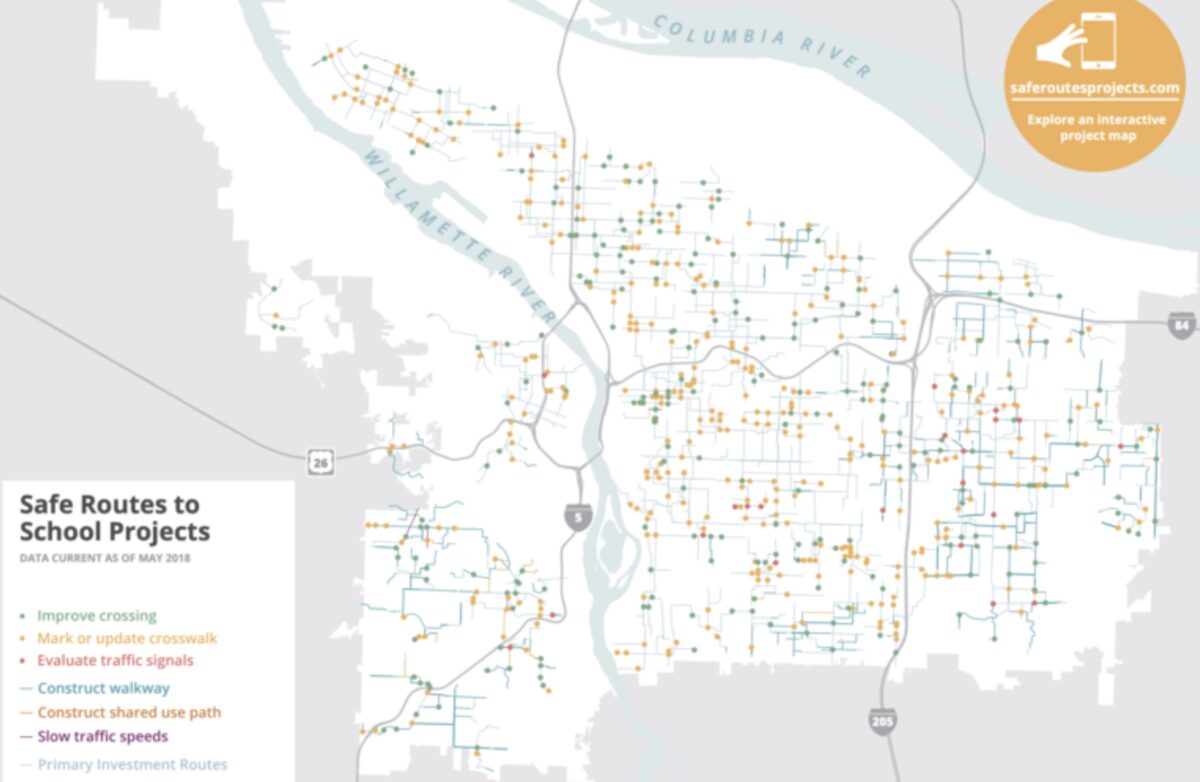

Portland’s own Safe Routes to School project plan says the top safety concerns for kids walking to school are unsafe crossings, missing sidewalks and traffic speed. The City of Portland used the map of key walking routes provided in this SRTS plan to guide the new camping ban. This map was designed to be an interactive tool for people to find out about SRTS projects throughout the city, however, so it does not serve as a very clear guide for which streets will be off-limits to homeless camps. It’s difficult to navigate the map to find out in complete detail how many of these streets there are around the city or what the network of banned streets will look like.

Sam Balto is a physical education teacher at Alameda Elementary School in northeast Portland who wants kids to be able to safely walk, bike and roll to school. Balto has organized and led “bike buses” – a.k.a., large groups of students and parents riding to school together en masse – to encourage families to ditch the carpool line and get to school by bike. In a statement to BikePortland, Balto said students will be better served by tactics like these than homeless camping bans.

Balto said the city should also increase traffic calming measures and expand existing initiatives – like the School Streets, Walking School Buses and Corner Greeters programs – to help kids use active transportation to get to school. He also wants the city to encourage more community-driven safety efforts like bike buses by compensating parents and community members for their involvement, and said this would “create a more equitable and sustainable student transportation model that would serve students and their families much better than removing houseless individuals.”

“I appreciate Mayor Wheeler wanting to improve the experience of children walking and biking to school, but removing houseless encampments along all school routes is not on the long list of initiatives that would improve safety for children,” Balto wrote in an email. “There are a lot of other ways to care about children’s safety and experience walking to school.”